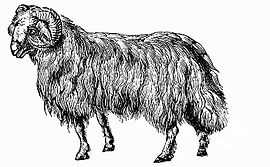

Fat-tailed sheep

The fat-tailed sheep is a general type of domestic sheep known for their distinctive large tails and hindquarters. Fat-tailed sheep breeds comprise approximately 25% of the world sheep population,[1] and are commonly found in northern parts of Africa, the Middle East, Pakistan, North India, Western China and Central Asia.[2]

The earliest record of this sheep variety is found in ancient Uruk (3000 BC) and Ur (2400 BC) on stone vessels and mosaics. Another early reference is found in the Bible (Leviticus 3:9), where a sacrificial offering is described which includes the tail fat of sheep.

Sheep were specifically bred for the unique quality of the fat stored in the tail area and the fat (called allyah) was used extensively in medieval Arab and Persian cookery. The tail fat is still used in modern cookery, though there has been a reported decline, with other types of fat and oils having increased in popularity.

Fat-tailed sheep are hardy and adaptable, able to withstand the tough challenges of desert life. When feed is plentiful and parasites not a major factor, fat-tailed sheep can be large in size and growth. The carcass quality of these sheep is quite good, with most of the fat concentrated in the tail area - it could account for as much as 10 pounds (4.5 kilograms) of the weight on a 60 pound (27 kilogram) carcass. The only fat-tailed breed seen frequently in the US are the Karakul and Tunis. There is a growing market for sheep of this type as the ethnic market is the fastest growing sector of lamb consumption in North America.

The wool from fat-tailed breeds is usually coarse and frequently has colored fibers. It would be of limited value in commercial markets. Today it is used primarily for rug-making and other cottage-type industries. Bedouin women make rugs and blankets from the wool. Some of their handiwork can be purchased in the villages of Egypt. Shearing in Egypt is done once or twice a year with hand clippers. There is a reluctance to use electric shears because of wool quality and the difficulty in getting replacement parts when they become dull or worn out.

The fat from fat-tailed sheep is called tail fat and is used in foods, candies, soaps.

The following quotation is from the short story Caravans, by James Michener (Random House, Copyright 1963). As quoted below it is being spoken in the story by an American expatriate consulate official travelling by caravan across Afghanistan in 1946. The story itself is a wonderful end-piece to read today, in light of the most recent war in Afghanistan, and will explain all manner of interesting historical and other facts about the country. This particular piece talks of the sheep that accompanied the caravan:

"Now the animals grew fat on abundant grass and on some days even the camels modified their grumblings. I spent hours watching our fat-tailed sheep, those preposterous beasts that looked not like sheep but like small-headed beetles stuck onto very long legs. They derived their name form an enormous tail, perhaps two feet across and shaped like a thick country frying pan covered with wool and rich with accumulated lanolin. The tail bumped up and down when the sheep walked, a grotesque afterpiece that served the same function as a camel’s hump: in good times it stored food which in bad times it fed back to the animal. I was told that the lanolin was not solid but could be moved about with the hands; certainly it could be eaten, as we proved in our pilaus, but now that the tails were at their maximum they made the ugly sheep seem like something an ungifted schoolboy had scratched on a tablet, and as I sat watching the huge bustles bounce up and down I used to speculate on how the beasts managed to copulate. To this day I don’t know."[3]

Breeds

- Afrikaner

- Awassi

- Balkhi

- Blackhead Persian

- Chios

- Karakul

- Zulu sheep, or Nguni

- Pedi

- Red Maasai

- Tunis

- Van Rooy

References

- ↑ Davidson, Alan (1999). Oxford Companion to Food. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 290–293. ISBN 0-19-211579-0.

- ↑ Reay Tannahill, 1973, Food in History p. 62 and 176. ISBN 0-8128-1437-1

- ↑ James A. Michener,Caravans, Jarrold & Sons Ltd., Norwich, Page 941, ISBN 0-064-0576-5