Fantastic Adventures

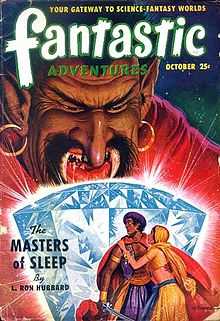

Fantastic Adventures was an American pulp science fiction magazine, published from 1939 to 1953 by Ziff-Davis. It was initially edited by Ray Palmer, who was also the editor of Amazing Stories, Ziff-Davis's other science fiction title. The first nine issues were in bedsheet format, but in June 1940 it switched to a standard pulp size. It was almost cancelled at the end of 1940, but the October 1940 issue had unexpectedly good sales, helped by a strong cover by J. Allen St. John for Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land. By May 1941 the magazine was on a regular monthly schedule. Historians of science fiction consider that Palmer was unable to maintain a consistently high standard of fiction, but Fantastic Adventures soon developed a reputation for light-hearted and whimsical stories. Much of the material was written by a small group of writers under both their own names and house names. The cover art, like those of many other pulps of the era, focused on beautiful women in melodramatic action scenes. One regular cover artist was H.W. McCauley, whose glamorous "MacGirl" covers were popular with the readers, though the emphasis on depictions of attractive and often partly clothed women did draw some objections from readers.

In 1949 Palmer left Ziff-Davis and was replaced by Howard Browne, who was knowledgeable and enthusiastic about fantasy fiction. Browne briefly managed to improve the quality of the fiction in Fantastic Adventures, and the period around 1951 has been described as the magazine's heyday. Browne lost interest when his plan to take Amazing Stories upmarket collapsed, however, and the magazine fell back into predictability. In 1952, Ziff-Davis launched another fantasy magazine, titled Fantastic, in a digest format; it was successful, and within a few months the decision was taken to end Fantastic Adventures in favor of Fantastic. The March 1953 issue of Fantastic Adventures was the last.

Publication history

Although science fiction (sf) had been published before the 1920s, it did not begin to coalesce into a separately marketed genre until the appearance in 1926 of Amazing Stories, a pulp magazine published by Hugo Gernsback. By the end of the 1930s the field was undergoing its first boom.[3] Gernsback lost control of Amazing Stories in 1929; it was sold to Teck Publications, and then in 1938 it was acquired by Ziff-Davis.[4][5] The following year Ziff-Davis launched Fantastic Adventures as a companion to Amazing; the first issue was dated May 1939, and the editor of Amazing, Ray Palmer, took on responsibility for the new magazine as well.[6]

Fantastic Adventures was initially published in bedsheet format,[note 1] the same size as the early sf magazines such as Amazing,[7][8] perhaps in order to attract fans who were nostalgic for the larger format.[9] It started as a bimonthly, but in January 1940 began a monthly schedule. Sales were weaker than for Amazing, however, and with the June issue the schedule reverted to bimonthly again. The size was also reduced to a standard pulp format, since that was cheaper to produce. Sales did not improve, and Ziff-Davis planned to make the October issue the last one. That issue carried Robert Moore Williams' Jongor of Lost Land, and had an attractive cover by J. Allen St. John; the combination proved to be so popular that October sales were twice the August figures. This convinced Ziff-Davis that the magazine was viable, and it was restarted in January 1941—as a bimonthly at first, but switching to monthly again in May of that year.[6][9]

Howard Browne took over as editor of both Amazing Stories and Fantastic Adventures in 1950. Browne preferred fantasy to science fiction, and enjoyed editing Fantastic Adventures, but when his plans for taking Amazing upmarket were derailed by the Korean War, he lost interest in both magazines for a while.[10][11] He let William Hamling take responsibility for both titles, and the quality declined. At the end of 1950 Ziff-Davis moved its offices from Chicago to New York; Browne relocated to New York, but Hamling decided to stay in Chicago, so Browne became more involved once again, and sf historians such as Brian Stableford and Mike Ashley consider the result to have been a definite improvement in quality.[8][10] Browne's interest in fantasy led him to start a new digest-sized magazine Fantastic in the summer of 1952; it was an immediate success, and led Ziff-Davis to convert Amazing Stories to digest format as well. The move away from the pulp format to digests was well under way in the early 1950s, and with Fantastic's success there was little reason to keep Fantastic Adventures going. It was merged with Fantastic; the last issue was dated March 1953, and the May–June issue of Fantastic added a mention of Fantastic Adventures to the masthead, though this disappeared with the following issue.[11]

Contents and reception

Palmer

The next issue contained "The Scientists' Revolt", by Edgar Rice Burroughs, a name guaranteed to help sales. Ashley comments that the story was unimpressive; it had been written as a palace intrigue set in contemporary Europe, but Burroughs had been unable to find a buyer. Palmer eventually acquired it, and rewrote it, setting it in the future. Despite the weakness of the lead story, the second issue was a marked improvement over the first, with well-received stories by Nelson S. Bond and John Russell Fearn (as "Thornton Ayre").[9] Burroughs returned to Fantastic Adventures in 1941, with a series of novelettes in his Carson of Venus series; there were four in all between March 1941 and March 1942, each with cover art by J. Allen St. John, and the result was a significant boost to Fantastic Adventures' circulation.[9]

Palmer enjoyed hoaxes, such as printing a photograph of a writer when in fact the name in question was a pseudonym. In the February 1944 issue of Fantastic Adventures he printed a letter in which the writer claimed to be a time-traveling scientist born in 1970, whose time machine was inspired by a story in the magazine. Palmer pretended to take it seriously, and printed an appeal to readers to find the scientist.[14] Palmer's most successful hoax was the "Shaver Mystery", a series of stories in which the author, Richard Shaver, explained all the wrecks and accidents on Earth as the result of interference by ancient machinery hidden underground. The series was enormously popular; all the Shaver Mystery stories were published in Fantastic Adventures' companion magazine, Amazing Stories (which led Ashley to describe Fantastic Adventures as a "haven" from the Shaver stories) but Shaver did also publish some competent fantasies in Fantastic Adventures.[9][14][15] The increased circulation enabled both Amazing and Fantastic Adventures to return to monthly publication in the late 1940s.[16]

Browne

Overall the quality was low, but according to sf historian Brian Stableford, "sf writers given carte blanche to write pure fantasy for [Fantastic Adventures] did often produce readable fiction with a distinctive whimsical and ironic flavour".[8] Critic John Clute's assessment was that it was inconsistent, "but there were some terrific tales in it. Not enough, but some."[18] Notable stories from the post-war era include Theodore Sturgeon's "Largo" and Raymond F. Jones' "The Children's Room". The artwork was generally of higher quality than the stories; Ashley describes Fantastic Adventures as "one of the best-illustrated magazines around". Regular artists included Virgil Finlay, Henry Sharp, Rod Ruth, and Malcolm Smith.[9] In Palmer's words, "It has been our experience that covers sell magazines—simply because they attract attention."[9] For the first year the cover art, while dramatic, was more likely to show an action scene with a male hero than a damsel in distress, but in August 1940 H.W. McCauley's cover showed a glamorous woman in a sparkling dress. Similar covers followed with increasing frequency, with readers and editors giving the various heroines the name of "MacGirl". Science fiction historian Paul Carter, commenting on the change from action scenes to alluring women on the covers, suggests that "surely the war had something to do with this".[19] Science fiction art often included spaceships as phallic symbols; author and critic Brian Aldiss remarked on a Fantastic Adventures cover, from March 1949, that included a submarine as a phallic symbol instead.[2] Readers' letters often objected to the attractive women and the implied sexual content, but the stories themselves were quite tame.[9]

Bibliographic details

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1939 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | ||||||||

| 1940 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | 2/5 | 2/6 | 2/7 | 2/8 | ||||

| 1941 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 3/5 | 3/6 | 3/7 | 3/8 | 3/9 | 3/10 | ||

| 1942 | 4/1 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | 4/5 | 4/6 | 4/7 | 4/8 | 4/9 | 4/10 | 4/11 | 4/12 |

| 1943 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | 5/6 | 5/7 | 5/8 | 5/9 | 5/10 | ||

| 1944 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | ||||||||

| 1945 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | |||||||

| 1946 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/5 | |||||||

| 1947 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 9/5 | 9/6 | 9/7 | 9/8 | ||||

| 1948 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 10/5 | 10/6 | 10/7 | 10/8 | 10/9 | 10/10 | 10/11 | 10/12 |

| 1949 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 11/5 | 11/6 | 11/7 | 11/8 | 11/9 | 11/10 | 11/11 | 11/12 |

| 1950 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 12/5 | 12/6 | 12/7 | 12/8 | 12/9 | 12/10 | 12/11 | 12/12 |

| 1951 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 13/7 | 13/8 | 13/9 | 13/10 | 13/11 | 13/12 |

| 1952 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 14/5 | 14/6 | 14/7 | 14/8 | 14/9 | 14/10 | 14/11 | 14/12 |

| 1953 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | |||||||||

| Issues of Fantastic Adventures, showing volume/issue number, and color-coded to show who was editor for each issue. The editor was Raymond Palmer from the beginning until the end of 1949; Howard Browne took over in January 1950 and remained in that role till the magazine folded. | ||||||||||||

- Ray Palmer: May 1939 – December 1949

- Howard Browne: January 1950 – April 1953

However, the editorial responsibility did not always reside with the named editor on the masthead. The editor-in-chief was senior to the managing editor, but at some points in the magazine's history it was the managing editor who was primarily responsible for the magazine. The following table shows who held which title, at which point:[9]

| Start month | End month | Editor-in-Chief | Managing Editor | Number of issues |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| May–39 | Jan–47 | B.G. Davis | Ray Palmer | 59 |

| Mar–47 | Oct–47 | Ray Palmer | Howard Browne | 5 |

| Nov–47 | Dec–49 | William Hamling | 26 | |

| Jan–50 | Feb–51 | Howard Browne | 14 | |

| Mar–51 | Mar–53 | Lila Shaffer | 25 |

Fantastic was initially bedsheet-sized and had a page count of 96, which increased to 144 when the publication was reduced to pulp-size in June 1940. It was initially priced at 20 cents. With the April 1942 issue the price increased to 25 cents, where it remained for the rest of the magazine's run, and the page count went up again to 240. From June 1943 to July 1945 there were 208 pages, and the count dropped to 176 with the October 1945 issue; then to 160 in July 1948, and only two issues later, in September 1948, the page count went down to 156. It dropped again to 144 with the June 1949 issue, but rose to 160 from September 1949 to August 1950. The September 1950 issue had 148 pages, and all the remaining issues had 130 pages.[9]

The magazine began as a bimonthly, but switched to a monthly schedule in January 1940, though this only lasted six issues. June 1940 was followed by August and October 1940 and January and March 1941. The May 1941 issue inaugurated another monthly period that lasted until August 1943, when the schedule switched back to bimonthly until the June 1944 issue. Fantastic then went on a quarterly schedule, beginning with the October 1944 issue; in October 1945 it became bimonthly again, though there was a gap between February and May 1946. From September 1947 to the end of the run the magazine was monthly. The volume numeration was regular, with a new volume starting at the beginning of each calendar year; the result was a variable number of issues in each volume, from a low of four in 1944 to a full 12 when the magazine was monthly, as it was for the last few years of its life. The last issue was volume 15 number 3.[9]

There were two British reprint editions. The first consisted of two numbered and undated issues, which appeared in May and June 1947 from Ziff-Davis in London. This was pulp-sized and 32 pages long; it contained stories from the wartime U.S. edition. The second series was published by Thorpe & Porter, in Leicester, and consisted of 24 undated issues, all but the first two of which were numbered. These began at 160 pages, and decreased, first to 128 and then to 96 pages. They were released between June 1950 and February 1954, and were abridged versions of U.S. editions dated from March 1950 to January 1953, as follows:[7][9]

| Number | British release date | Corresponding U.S. issue |

|---|---|---|

| 1 (unnumbered) | June 1950 | Mar 1950 |

| 2 (unnumbered) | August 1950 | Apr 1950 |

| 3 | October 1950 | May 1950 |

| 4 | December 1950 | September 1950 |

| 5 | January 1951 | October 1950 |

| 6 | March 1951 | August 1950 |

| 7 | April 1951 | February 1951 |

| 8 | November 1951 | January 1951 |

| 9 | February 1952 | February 1950 |

| 10 | March 1952 | November 1950 |

| 11 | April 1952 | December 1950 |

| 12 | July 1952 | March 1951 |

| 13 | September 1952 | April 1951 |

| 14 | October 1952 | May 1951 |

| 15 | November 1952 | August 1951 |

| 16 | January 1953 | June 1951 |

| 17 | February 1953 | September 1951 |

| 18 | April 1953 | October 1951 |

| 19 | June 1953 | April 1952 |

| 20 | July 1953 | June 1952 |

| 21 | August 1953 | July 1950 |

| 22 | September 1953 | January 1953 |

| 23 | October 1953 | December 1951 |

| 24 | February 1954 | December 1952 |

The contents were initially identical to the U.S. editions, but starting with issue #13 at least one story was dropped.[7][9]

Starting in 1941, unsold issues of Fantastic Adventures were rebound, three together, with a new cover, titled Fantastic Adventures Quarterly. There were eight of these quarterly issues between Winter 1941 and Fall 1943; they were priced at 25 cents and given a volume numbering from volume 1 number 1 to volume 2 number 4. Another similar series was started in Summer 1948, for 50 cents; there were eleven of these, running from volume 6 number 1 to volume 9 number 1, finishing with the Spring 1951 issue and omitting Spring 1949.[7][9]

In 1965, Sol Cohen acquired both Amazing Stories and Fantastic from Ziff-Davis, along with reprint rights to all the stories that had appeared in the Ziff-Davis science fiction magazines, including Fantastic Adventures.[20] Cohen published multiple reprint titles, and frequently reprinted stories from Fantastic Adventures. In particular, the following issues took their contents mostly or completely from Fantastic Adventures:[9][21]

- Fantastic Adventures Yearbook. One issue in the summer of 1970, no number, dated only with the year. Reprinted six stories from Fantastic Adventures that had originally appeared between 1949 and 1952.

- Thrilling Science Fiction. Issues 16 and 20 (Summer 1970 and Summer 1971).

- Science Fiction Adventures. January 1974 issue.

- Science Fantasy. All four issues, from 1970 to 1971.

- The Strangest Stories Every Told. One issue, Summer 1970.

- Weird Mystery. There were four issues of this magazine between Fall 1970 and Summer 1971; the contents were drawn largely from Fantastic Adventures.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fantastic Adventures. |

Notes

Footnotes

- ↑ Peter Nicholls, "Bedsheet", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, p. 102.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Aldiss & Wingrove, Trillion Year Spree, pp. 222, 463, 464.

- ↑ Malcolm Edwards & Peter Nicholls, "SF Magazines", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, pp. 1066–1068.

- ↑ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 76.

- ↑ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 115.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 6.6 6.7 6.8 Ashley, Time Machines, pp. 142–146.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 "Fantastic Adventures", in Tuck, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy, Vol. 3, pp. 558–559.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 Brian Stableford, "Fantastic Adventures", in Clute & Nicholls, Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, p. 404.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 9.4 9.5 9.6 9.7 9.8 9.9 9.10 9.11 9.12 9.13 9.14 9.15 9.16 9.17 9.18 9.19 9.20 9.21 9.22 9.23 Mike Ashley, "Fantastic Adventures", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 232–240.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Ashley, Transformations, p. 7.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ashley, Transformations, pp. 48–50.

- ↑ See the individual issues. For convenience, an online index is available at "Magazine:Fantastic Adventures — ISFDB". Al von Ruff (Publisher). Retrieved 28 January 2011. An index to the British reprints is at "Visco navigation". Terry Gibbons. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ de Camp, Science-Fiction Handbook, p. 120.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Ashley, Time Machines, p. 178.

- ↑ Ashley, Time Machines, p. 183.

- ↑ Ashley, History of the Science Fiction Magazine, Vol. 3, p. 24.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, p. 6.

- ↑ Clute, Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia, p. 101.

- ↑ Carter, Creation of Tomorrow, p. 183.

- ↑ Ashley, Transformations, p. 228.

- ↑ Mike Ashley, "Fantastic Adventures Yearbook", in Tymn & Ashley, Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines, pp. 240–241.

References

- Aldiss, Brian; Wingrove, David (1986). Trillion Year Spree:The History of Science Fiction. London: Gollancz. ISBN 0-575-03943-4.

- Ashley, Michael (1976). The History of the Science Fiction Magazine Vol. 3 1946–1955. Chicago: Contemporary Books, Inc. ISBN 0-8092-7842-1.

- Ashley, Mike (2000). The Time Machines:The Story of the Science-Fiction Pulp Magazines from the beginning to 1950. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-865-0.

- Ashley, Mike (2005). Transformations: The Story of the Science Fiction Magazines from 1950 to 1970. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-779-4.

- Carter, Paul A. (1977). The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-04211-6.

- Clute, John (1995). Science Fiction: The Illustrated Encyclopedia. New York: Dorling Kindersley. ISBN 0-7894-0185-1.

- Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St. Martin's Press, Inc. ISBN 0-312-09618-6.

- de Camp, L. Sprague (1953). Science-Fiction Handbook: The Writing of Imaginative Fiction. New York: Hermitage House.

- Tuck, Donald H. (1982). The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction and Fantasy: Volume 3. Chicago: Advent: Publishers, Inc. ISBN 0-911682-26-0.

- Tymn, Marshall B.; Ashley, Mike (1985). Science Fiction, Fantasy and Weird Fiction Magazines. Westport CT: Greenwood Press. ISBN 0-313-21221-X.