False friend

| Linguistics |

|---|

| Theoretical linguistics |

| Descriptive linguistics |

|

Applied and experimental linguistics |

| Related articles |

| Linguistics portal |

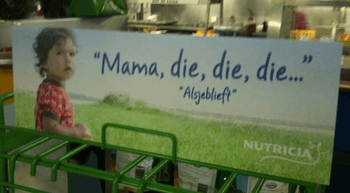

False friends are pairs of words or phrases in two languages or dialects (or letters in two alphabets)[1] that look or sound similar, but differ significantly in meaning. An example is the English embarrassed and the Spanish embarazada, which does not in fact mean 'embarrassed' but rather 'pregnant'.

Often, there is a partial overlap in meanings, which creates additional complications: e.g. Spanish lima, meaning 'lime' (the fruit) and 'collar beam' (part of a roof construction), but also 'file' (the tool). Only when lima is used to mean the fruit does it become an accurate translation. Most difficult of all is the case of an overlap in meaning that does not catch all the nuances of each word—for instance, the French demande simply means a 'request', which is similar to a 'demand' in English and 'demandar' in Spanish but carries significant differences, as well.

The term should be distinguished from "false cognates", which are similar words in different languages that appear to have a common historical linguistic origin (whatever their current meaning) but actually do not.

As well as complete false friends, use of loanwords often results in the use of a word in a restricted context, which may then develop new meanings not found in the original language.

Implications

False friends can cause difficulty for students learning a foreign language, particularly one that is related to their native language, because students are likely to identify the words wrongly due to linguistic interference. For this reason, teachers sometimes compile lists of false friends as an aid for their students.

False friends are also a frequent source of difficulty between speakers of different dialects of the same language. Speakers of British English and American English sometimes have this problem, which was alluded to in George Bernard Shaw's statement "England and America are two countries separated by a common language".[2] For example, in the UK (and in other Commonwealth countries), to "table" a motion means to place it on the agenda (to bring it to the table for consideration), while in the US it means exactly the opposite—"to remove it from consideration" (to lay it aside on the table rather than hold it up for consideration).[3] Similarly, the Spanish word limón refers to a lemon in some parts of the Spanish-speaking world but a lime in others.

A particularly problematic case with false friends occurs when one of the two words is obscene or derogatory (a cacemphaton,[4] Greek for "ill-sounding"[5]). Well-known examples are the words 'fag' (in British English referring to a cigarette, but in American English is an offensive term for a homosexual) and Spanish coger (meaning to take in Spain and parts of Central America, but also to fuck in Mexico and Argentina). "Fagot" in Dutch means a bassoon, cognate to a derogatory English term for a male homosexual. "Neger" is the neutral Dutch term for a black person but cognates to "Nigger" in English, which is an offensive term for a black person. In some cases this has led to significant controversy, e.g. when Tiger Woods referred to himself as a 'spaz' (in American English meaning a "clumsy person", but in British English an offensive term a for disabled person).[6]

Causes

From the etymological point of view, false friends can be created in several ways.

Shared etymology

If Language A borrowed a word from Language B, or both borrowed the word from a third language or inherited it from a common ancestor, and later the word shifted in meaning or acquired additional meanings in at least one of these languages, a native speaker of one language will face a false friend when learning the other. Sometimes, presumably both senses were present in the common ancestor language, but the cognate words got different restricted senses in Language A and Language B.[citation needed]

For example, the words preservative (English), préservatif (French), Präservativ (German), prezervativ (Romanian, Czech, Croatian), preservativ or prezervativ (Slovenian), preservativo (Italian, Spanish, Portuguese), prezerwatywa (Polish), презерватив prezervativ (Russian, Serbian, Bulgarian, Ukrainian, Macedonian), prezervatif (Turkish), præservativ (Danish), prezervatyvas (Lithuanian), Prezervatīvs (Latvian) and preservatiu (Catalan) are all derived from the Latin word praeservativum. But in all of these languages except English, the predominant meaning of the word is now 'condom'.[citation needed]

Actual, which in English is usually a synonym of real, has a different meaning in other European languages, in which it means 'current' or 'up-to-date', and has the logical derivative as a verb, meaning 'to make current' or 'to update'. Actualise (or 'actualize') in English means 'to make a reality of'.[7]

The word friend itself has cognates in the other Germanic languages; but the Scandinavian ones (like Swedish frände, Danish frænde) predominantly mean 'relative' . The original Proto-Germanic word meant simply 'someone who one cares for' and could therefore refer to both a friend and a relative, but lost various degrees of the 'friend' sense in Scandinavian languages, while it mostly lost the sense of 'relative' in English. (The plural friends still but rarely may be used for "kinsfolk", as in the Scottish proverb Friends agree best at a distance, quoted in 1721.)

The Italian word magazzino, Romanian magazin, French magasin, Dutch magazijn, Greek μαγαζί (magazi) comes from Arabic مخزان (makhzān) — Persian مغازه - (magaze) is used for a depot, store, or warehouse, just like the Spanish word almacén, which incorporated the Arabic article (al-mazen). In English the word magazine has also the meaning of 'periodic publication'. The word magazine has the same meaning in French. In Serbian, there are two similar words: magacin, representing the former, and magazin representing the latter meaning. To add confusion, there is an extra meaning of magazine (firearms) in several languages (with accordingly different spellings). Russian магазин (magazin) means 'shop' and 'magazine (firearms)', but not 'periodic publication'.

The Finnish and Estonian languages are both part of the non-Indo-European Uralic languages; they share a similar grammar as well as several individual words, though sometimes as false friends: e.g. the Finnish word for 'south', etelä is close to the Estonian word edel, but the latter means south-west. However, the Estonian word for south, lõuna, is close to the Finnish word lounas, which means south-west.[citation needed]

Homonyms

In certain cases, false friends evolved separately in the different languages. Words usually change by small shifts in pronunciation accumulated over long periods and sometimes converge by chance on the same pronunciation or look despite having come from different roots.[citation needed]

For example, German Rat (pronounced with a long "a") (= 'council') is cognate with English read and German and Dutch Rede (= 'speech', often religious in nature) (hence Æthelred the 'Unready' would not heed the speech of his advisors, and the word unready is cognate with the Dutch word onraad meaning trouble, danger), while English and Dutch rat for the rodent has its German cognate Ratte.[citation needed]

In another example, the word bra in the Swedish language means 'good'. Scots also has the word braw, which has much the same use and shares etymology. Swedish has also the word god, which is used primarily to describe food and drink but also in the following expression, which does not need translation into English, en god man, as in "a good song", "a good book" or "Good day!" Bra has the same meaning in Norwegian as in Swedish. In both languages Bara bra (Sw.) or Bare bra (No.) as a response to "How are you?" is very common (likewise Ha det bra as a form of "Good bye"). In English, 'bra' is short for the French brassière, which is an undergarment that supports the breasts. The full English spelling, 'brassiere', is now a false friend in and of itself (the modern French term for brassiere is soutien-gorge).

In Swedish, the word rolig means 'fun' (as in "It was a fun party"), while in the closely related languages Danish and Norwegian it means 'calm' (as in "he was calm despite all the furor around him"). However, the Swedish original meaning of 'calm' is retained in some related words such as ro, 'calmness', and orolig, 'worrisome, anxious', literally 'un-calm'.[citation needed]

Homoglyphs

For example, Latin P came to be written like Greek rho (written Ρ but pronounced [r]), so the Roman letter equivalent to rho was modified to R to keep it distinct.[8]

An Old and Middle English letter has become a false friend in modern English: the letters thorn (þ) and eth (ð) were used interchangeably to represent voiced and voiceless dental fricatives now written in English as th (as in "thick" and "the"). Though the thorn character (whose appearance was usually similar to the modern "p") was most common, the eth could equally be used. Due to its similarity to an oblique minuscule "y", an actual "Y" is substituted in modern pseudo-old-fashioned usage as in "Ye Olde Curiositie Shoppe"; the first word means and should be pronounced "the", not "ye" (archaic form of "you").[9]

Homoglyphs occur also by coincidence. For example, Finnish tie means "road"; the pronunciation is [tie], unlike English [tai], which in turn means "or" in Finnish.[10][11]

Pseudo-anglicisms

Pseudo-anglicisms are new words formed from English morphemes independently from an analogous English construct and with a different intended meaning.[citation needed]

For example, in German: Oldtimer refers to an old car (or antique aircraft) rather than an old person, while Handy refers to a mobile phone. Beamer refers to a computer projector or video projector rather than a car or motorcycle manufactured by BMW. In Dutch, the words "Oldtimer" and "Beamer" are used in the same meaning as in German.

In Norwegian, "trailer" refers to a truck and trailer, or sometimes only the truck, while "truck" means a forklift.

French and German have many pseudo-anglicisms derived from English gerunds. For example, a "parking" is in both languages a parking lot rather than the act of parking a car, and a "lifting" is a face-lift.

Japanese is replete with pseudo-anglicisms, known as wasei-eigo ("Japan-made English").

In the SeSotho group of languages spoken in South Africa, pushback refers to a combed-back hairstyle commonly worn by black women with chemically straightened hair; and stop-nonsense refers to pre-fabricated concrete slabs used as fencing.[citation needed]

Semantic change

In bilingual situations, false friends often result in a semantic change—a real new meaning that is then commonly used in a language. For example, the Portuguese humoroso ('capricious') changed its referent in American Portuguese to 'humorous', owing to the English surface-cognate humorous.[citation needed]

"Corn" was originally the dominant type of grain in a region (indeed "corn" and "grain" are themselves cognates from the same Indo-European root). It came to mean usually cereals in general in the British Isles in the nineteenth century e.g. Corn laws, but maize in North America, and now just maize also in the British Isles.[citation needed]

The Italian word confetti (sugared almonds) has acquired a new meaning in English and French - in Italian, the corresponding word is coriandoli.[12]

The American Italian fattoria lost its original meaning 'farm' in favour of 'factory' owing to the phonetically similar surface-cognate English factory (cf. Standard Italian fabbrica 'factory'). Instead of the original fattoria, the phonetic adaptation American Italian farma (Weinreich 1963: 49) became the new signifier for 'farm'—see "one-to-one correlation between signifiers and referents".[13]

This phenomenon is analysed by Ghil'ad Zuckermann as "(incestuous) phono-semantic matching".

Use by Hemingway

Ernest Hemingway in For Whom the Bell Tolls made deliberate use of false friends as one of the devices intended to convey to the reader that English conversations in the book in fact represent Spanish. Thus, he used "rare" rather than "strange" to represent the Spanish raro, and "syndicate" rather than "trade union" for the Spanish sindicato.

See also

- False etymology

- Translation

- OpenTaal Grammar checking

References

- ↑ "Italian False Friends". To Be a Travel Agent.

- ↑ "Quotationspage.com". Quotationspage.com. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ↑ "Merriam-Webster definition of verb "table"". Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2012-03-13.

- ↑ Silva Rhetoricae, Cacemphaton.

- ↑ κακέμφατος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

- ↑ "A Brief History of "Spaz"". Language Log. 2006-04-13. Retrieved 2013-09-24.

- ↑ Mollin, Sandra (2006), Euro-English: assessing variety status

- ↑ "Language and Linguistics/R".

- ↑ "Want to meet two extinct letters of the alphabet? Learn what “thorn” and “wynn” sounded like".

- ↑ "Road".

- ↑ "Tai".

- ↑ Confetto in Enciclopedia Treccani.

- ↑ Zuckermann, Ghil'ad (2003). Language Contact and Lexical Enrichment in Israeli Hebrew. Houndmills: Palgrave Macmillan, (Palgrave Studies in Language History and Language Change, Series editor: Charles Jones). p. 102. ISBN 1-4039-1723-X.

External links

| Look up false friend in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikibooks has a book on the topic of: False Friends of the Slavist |

- An online hypertext bibliography on false friends

- German/English false friends

- Spanish/English false friends

- French/English false friends

- Italian/English false friends

- English/Russian false friends

- English/Dutch false friends

- LanguageTool support for false friends according to rules in this format.