Falklands Crisis (1770)

The Falklands Crisis of 1770 was a diplomatic standoff between Great Britain and Spain over possession of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic Ocean. These events were nearly the cause of a war between Britain and Spain (backed by France), and all three countries were poised to dispatch armed fleets to defend the rival claims to sovereignty of the barren but strategically important islands.

Ultimately, a lack of French support for Spain defused the tension, and Spain and Britain reached an inconclusive compromise in which both nations maintained their settlements but neither relinquished its claim of sovereignty over the islands.

Background

Several British and Spanish historians maintain their own explorers discovered the islands, leading to claims from both sides on the grounds of prior discovery. In January 1690, English sailor John Strong, captain of the Welfare, sailed between the two principal islands and called the passage "Falkland Channel" (now Falkland Sound), after Anthony Cary, 5th Viscount Falkland. The island group later took its English name from this body of water.[1]

During the 17th century, the English government was to make a claim, but it was only in 1748 – with the report of Admiral Lord Anson – that London began to give the matter its serious attention. Spanish objections to a planned British expedition had the effect of drawing up the battle lines and the matter was put to one side for the time being. An uncertain equilibrium might have remained but for the unexpected intervention of a third party, France.

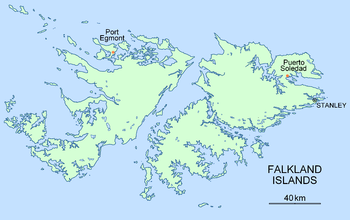

After the conclusion of the Seven Years' War, the French were eager to improve their position in the South Atlantic. Louis de Bougainville landed in the Falklands in 1764, with the intention of establishing a permanent base at Port Louis. In 1765, the one unbeknown to the other, the British under John Byron made their own landing at Port Egmont in the west. Responding to Spanish pressure, the French handed over Port Louis to their closest ally in 1767 and it was renamed Puerto Soledad.

Crisis

In June 1770, the Spanish governor of Buenos Aires, Francisco de Paula Bucareli y Ursua, sent five frigates under General Juan Ignacio de Madariaga to Port Egmont. On 4 June, a Spanish frigate anchored in the harbour; she was presently followed by four others, containing some 1400 marines. The small British force was under the command of Commander George Farmer.[2] Madariaga wrote to Farmer on 10 June that having with him fourteen hundred troops and a train of artillery, he was in a position to compel the English to quit, if they hesitated any longer. Farmer replied that he should defend himself to the best of his power; but when the Spaniards landed, after firing his guns, Farmer capitulated on terms, an inventory of the stores being taken, and the British were permitted to return to their country in the Favourite.

British response

When Parliament assembled in November, the MPs, outraged by this insult to national honour, demanded action from the North government. Many were angered by what they saw as Britain's failure to prevent France from annexing Corsica in 1768 and feared a similar situation occurring in the Falklands.[3] The Foreign Office "began to mobilise for a potential war".[4]

Amid this flurry of threats and counter-threats, the Spanish attempted to strengthen their position by winning the support of France, invoking the Pacte de Famille between the two Bourbon crowns. For a time it looked as if all three countries were about to go to war, especially as the Duc de Choiseul, the French minister of war and foreign affairs, was in a militant mood. But Louis XV took fright, telling his cousin Charles III that "My minister wishes for war, but I do not."[5] Choiseul was dismissed from office, retiring to his estates, and without French support the Spanish were obliged to seek a compromise with the British.

Spanish compromise

On 22 January 1771, the Prince of Masseran (ambassador of the Spanish Court) delivered a declaration, in which the King of Spain "disavows the violent enterprise of Bucareli," and promises "to restore the port and fort called Egmont, with all the artillery and stores, according to the inventory." The agreement also stated: "this engagement to restore port Egmont cannot, nor ought, in any wise, to affect the question of the prior right of sovereignty of the Malouine, otherwise called Falkland's islands."[6][7]

This concession was accepted by the Earl of Rochford, who declared that he was authorised "to offer, in his majesty's name, to the King of Great Britain, a satisfaction for the injury done him, by dispossessing him of port Egmont;" and, having signed a declaration, expressing that Spain "disavows the expedition against port Egmont, and engages to restore it, in the state in which it stood before the 10th of June, 1770, his Britannick majesty will look upon the said declaration, together with the full performance of the engagement on the part of his catholick majesty, as a satisfaction for the injury done to the crown of Great Britain."[8]

Aftermath

The British restored their base at Port Egmont. Although the whole question of sovereignty was simply sidestepped, it would become a source of future trouble. Samuel Johnson described the implications of the crisis in his pamphlet "Thoughts on the late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Island",[8] looking at the British problem in holding such remote islands against a hostile mainland: "a colony that could never become independent, for it could never be able to maintain itself."

The crisis greatly strengthened the position of the British Prime Minister Lord North, and fostered a belief during the American War of Independence that France would not dare to intervene in British colonial affairs. Conversely, it effectively ended the career of Choiseul, who held no subsequent major office in the French government. However, Vergennes soon rose to power and held similar views to Choiseul on the necessity on reversing Britain's gains in the Seven Years War to restore the Balance of Power, setting the scene for France's future involvement in the American War.

See also

- Sovereignty of the Falkland Islands

- History of the Falkland Islands

- Timeline of the history of the Falkland Islands

- Re-establishment of British rule on the Falklands (1833)

References

Citations

- ↑ Whiteley, p. 95 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑

"Farmer, George". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

"Farmer, George". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - ↑ Simms, pp. 560–63 Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ Roger, Nicholas (1998), Crowds, Culture, and Politics in Georgian Britain, Oxford University Press, p. 103

- ↑ Green, Walford Davis (1906), William Pitt, Earl of Chatham, and the Growth and Division of the British Empire, 1708–1778, GP Putnam's Sons, p. 328

- ↑ From Spain’s declaration; original French text in British and Foreign State Papers 1833-1834 (printed London 1847), pp. 1387-1388; English translation from Julius Goebel, The Struggle for the Falkland Islands, New York 1927, pp. 358-359.

- ↑ "Getting it right: the real history of the Falklands/Malvinas A reply to the Argentine seminar of 3 December 2007".

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Johnson, Samuel, Thoughts on the late Transactions Respecting Falkland's Island (pamphlet)

Sources

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Farmer, George". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: "Farmer, George". Dictionary of National Biography. London: Smith, Elder & Co. 1885–1900. - Goebel, Julius. The Struggle for the Falkland Islands: A Study in Legal and Diplomatic History. Oxford University Press, 1927.

- Laver, Roberto C. The Falklands/Malvinas Case. Martinus Nijhoff, 2001. ISBN 90-411-1534-X.

- Rice, GW (2010), "British Foreign Policy and the Falkland Islands Crisis of 1770–71", The International History Review 32 (2): 273–305.

- Simms, Brendan. Three Victories and a Defeat: The Rise and Fall of the First British Empire. Penguin Books, 2008.

- Whiteley, Peter. Lord North: The Prime Minister Who Lost America. Hambledon Press, 1996.