Anatomical terms of motion

This article is about anatomical terms of motion, for a general overview of anatomical terminology see Anatomical terminology, or for anatomical terms of location see Anatomical terms of location.

The voluntary movement of body structures is accomplished by the contraction of muscles. Muscles may move parts of the skeleton relatively to each other, or may move parts of internal organs relatively to each other. All such movements are classified by the directions in which the affected structures are moved. In human anatomy, all descriptions of position and movement are based on the assumption that the body is in its complete medial and abduction stage and is in anatomical position.

Classifications of motion

Motions are classified after the planes they engage,[1]:212 although motions of the human body are more often than not a combination of differing motions.[2]

Gross movements are big body movements relating to the use of the large muscles of the human body, such as those in the legs, arms, and abdomen, as opposed to fine movement of for example fingers or wrist.

According to the movements of joints

Motions can be split into three categories as per how they engage different joints of the body:

- A gliding motion occurs between flat surfaces, such as in the intervertebral discs or between the carpal and metacarpal bones of the hand.

- An angular motion occurs over synovial joints and causes them to either increase or decrease angles between bones.

- A rotational motion moves a structure in a rotational motion in several planes.[1]:212

According to the direction of the movement

Apart from this motions can also be divided into:[2]

- Linear motions (or translatory motions), which move in a line between two points. A rectilinear motion refers to a motion in a straight line between two points, whereas a curvilinear motion refers to a motion following a curved path.

- Angular motions (or rotary motions) occur when an object is around another object increasing or decreasing the angle. The different parts of the object do not move the same distance. Examples include a movement of the knee, where the lower leg changes angle compared to the femur, or movements of the ankle (plantar and dorsiflexion).

Motions of the body

Motions occurring over joints are also known as joint movements or osteokinematics, and depend on the joints of the body (mainly synovial. All motions that are created by the body are considered to be a mixture of or a single contribution of the following types of movement.

Most terms of a motion have clear opposites, and as such, are treated below in pairs.

General motion

Flexion and extension

Flexion and extension describe movements that affect the angle between two parts of the body.

Flexion describes a bending movement that decreases the angle between two parts. Bending the elbow, or clenching a hand into a fist, are examples of flexion. When sitting down, the knees are flexed. Flexion of the hip or shoulder moves the limb forward (towards the anterior side of the body).

Extension is the opposite of flexion, describing a straightening movement that increases the angle between body parts. In a conventional handshake, the fingers are fully extended. When standing up, the knees are extended. Extension of the hip or shoulder moves the limb backward (towards the posterior side of the body).

Abduction and adduction

Abduction and adduction refer to motions that move a structure away from or towards the centre of the body.[3] :590-1

Abduction refers to a motion that pulls a structure or part away from the midline of the body (or, in the case of fingers and toes, spreading the digits apart, away from the centerline of the hand or foot). Abduction of the wrist is called radial deviation. Raising the arms laterally, such as when skiing, is an example of abduction at the shoulder. [3]:590-1

Adduction refers to a motion that pulls a structure or part toward the midline of the body, or towards the midline of a limb. Dropping the arms to the sides, or bringing the knees together, are examples of adduction. In the case of the fingers or toes, adduction is closing the digits together. Adduction of the wrist is called ulnar deviation. Bringing the arms closer to the body is an example of adduction at the shoulder. [3]:590-1 The inner thigh houses some adductors, including the adductor brevis, adductor longus, adductor magnus, and pectineus. The latissimus dorsi is a good example for the humerus. [citation needed]

Rotation

Rotation of body parts is referred to as internal or external, referring to rotation towards or away from the center of the body. [3]:590-1

Internal rotation (or medial rotation) refers to rotation towards the axis of the body. For example, a roman salute, in which the arm is placed against the chest, is an example of internal rotation. [3]:590-1 The pectoralis major and subscapularis both medially rotate the humerus. The adductor longus and adductor brevis both medially rotate the thigh. [citation needed]

External rotation (or lateral rotation) refers to rotation away from the center of the body. for example, external rotation of the toes would turn the toes or the flexed forearm outwards (away from the midline). The sartorius laterally rotates the femur. The infraspinatus and teres minor both laterally rotate the humerus. [citation needed]

Elevation and depression

Elevation refers to movement in a superior direction. For example, raising the arm upwards is elevating the arm.

Depression refers to movement in an inferior direction, the opposite of elevation. Opposite to the upper fibers, the lower half of the trapezius aids in depressing the apex of the shoulder.

Special motions of the hands and feet

Flexion and extension of the foot

Dorsiflexion and plantarflexion refers to flexion (dorsiflexion) or extension of the foot at the ankle.

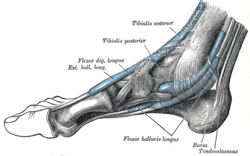

Dorsiflexion is the movement which decreases the angle between the dorsum (superior surface) of the foot and the leg, so that the toes are brought closer to the shin. [4]:123 and applies to the upward movement of the foot at the ankle joint. The muscles involved include those of the Anterior compartment of leg, specifically tibialis anterior muscle, extensor hallucis longus muscle, extensor digitorum longus muscle, and peroneus tertius. The range of motion for dorsiflexion indicated in the literature varies from 12.2[5] to 18[6] degrees.[7] Foot drop is a condition, that occurs when dorsiflexion is difficult for an individual that is walking.

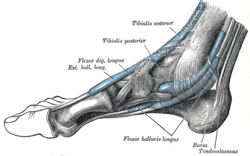

Plantarflexion (or plantar flexion) is the movement which increases the approximate 90 degree angle between the front part of the foot and the shin, as when depressing an automobile pedal or standing on the tiptoes. The word "plantar" is commonly understood in medical terminology as the bottom of the foot - it translates as "toward the sole". This movement is normally performed in either the supine, prone or standing position. Primary muscles for plantar flexion are situated in the Posterior compartment of leg, namely the superficial Gastrocnemius, Soleus and Plantaris (only weak participation), and the deep muscles Flexor hallucis longus, Flexor digitorum longus and Tibialis posterior. Muscles in the Lateral compartment of leg also weakly participation, namely the Fibularis longus and Fibularis brevis muscles. Those in the lateral compartment only have weak participation in plantar flexion though. The range of motion for plantar flexion is usually indicated in the literature as 30° to 40°, but sometimes also 50°. The nerves are primarily from the sacral spinal cord roots S1 and S2. Compression of S1 roots may result in weakness in plantarflexion, these nerves run from the lower back to the bottom of the foot. [citation needed]

-

Tibialis anterior muscle labeled at top center, and extensor muscles labeled at right.

-

thumb|Flexor muscles visible at bottom center.

Flexion and extension of the hand

Palmarflexion and dorsiflexion refer to movement of the flexion (palmarflexion) or extension (dorsiflexion) of the hand at the wrist. For example, prayer is often conducted with the hands dorsiflexed.[3]:591-3

Palmarflexion is one of the movements of the wrist and hand which takes place at the wrist joint, where the angle between the palm and the forearm is decreased. In this context, this consists of bending the hand towards the inside of the wrist, an action known as flexion in anatomical terms. [3]:591-3

Dorsiflexion refers to extension at the wrist joint. The opposite of this is dorsiflexion or extension; in the case of palmar extension, the angle between the back (dorsum) of hand and the forearm is reduced - specifically, the hand bends away from the inside of the wrist.[3]:591-3

-

Praying Hands by Albrecht Dürer, demonstrating Dorsiflexion of the hands during a medieval commendation ceremony.

Pronation and supination

Pronation and supination refer to rotation of the forearm or foot so that in the anatomical position the palm or sole is facing anteriorly (supination) or posteriorly (pronation). [3]:591-2

Pronation at the forearm is a rotational movement at the radioulnar joint, or of the foot at the subtalar and talocalcaneonavicular joints.[8][9] For the forearm, when standing in the anatomical position, pronation will move the palm of the hand from an anterior-facing position to a posterior-facing position without an associated movement at the shoulder (glenohumeral joint). This corresponds to a counterclockwise twist for the right forearm and a clockwise twist for the left (when viewed superiorly). In the forearm, this action is performed by pronator quadratus and pronator teres muscle. Brachioradialis puts the forearm into a midpronated/supinated position from either full pronation or supination. For the foot, pronation will cause the sole of the foot to face more laterally than when standing in the anatomical position.

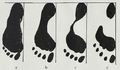

Pronation of the foot is a compound movement that combines abduction, eversion, and dorsiflexion. Regarding posture, a pronated foot is one in which the heel bone angles inward and the arch tends to collapse. Pronation is the motion of the inner and outer ball of the foot with the heel bone.[10] One is said to be "knock-kneed" if one has overly pronated feet. It flattens the arch as the foot strikes the ground in order to absorb shock when the heel hits the ground, and to assist in balance during mid-stance. If habits develop, this action can lead to foot pain as well as knee pain, shin splints, achilles tendinitis, posterior tibial tendinitis, piriformis syndrome, and plantar fasciitis[citation needed].

Supination of the forearm occurs when the forearm or palm face to the front (anteriorly) of the body. This action is performed by the biceps brachii and the supinator muscle. The arm is supine when in the anatomical position,[11] and the supine position is also used when taking blood pressure. Supination of the foot occurs when the foot rolls outwards, placing most of the weight onto the outside of the foot and raising the arch. It is a compound movement that combines adduction, inversion, and plantar flexion.

-

Supination and pronation of the foot.

-

A pronated arm, fingers curled toward elbow, and wrist turned so that knuckles point directly away from the head.

-

A supinated arm, wrist turned so that the knuckles point towards the head.

Inversion and eversion

Inversion and eversion refer to movements that tilt the sole of the foot away from (eversion) or towards (inversion) the midline of the body. [3]:591

Eversion is the movement of the sole of the foot away from the median plane. It occurs at the subtalar joint. The muscles involved in this include Fibularis longus and fibularis brevis, which are innervated by the superficial fibular nerve. Some sources also state that the fibularis tertius everts.[4]:108 - Inversion is the movement of the sole towards the median plane (as when an ankle is twisted). The muscles Tibialis anterior and tibialis posterior invert. Some sources also state that the triceps surae and extensor hallucis longus invert.[4]:123 Inversion occurs at the subtalar joint and transverse tarsal joint.[12]

-

Eversion of the right foot.

-

Inversion of the right foot.

-

Peroneus longus and peroneus brevis (centre left), the primary muscles involved in eversion.

-

Tibialis anterior and posterior (centre top), the primary muscles involved in inversion.

Other special motions

Such terms include:

- Anterograde and Retrograde flow, refers to movement of blood or other fluids in a normal (anterograde) or abnormal (retrograde) direction.

- Protraction and Retraction refer to an anterior (protraction) or posterior (retraction) movement of the arm at the shoulders. The major muscles involved in retraction include the Rhomboid major muscle, Rhomboid minor muscle and Trapezius muscle, [13][14] whereas the major muscles involved in protraction include the serratus anterior and pectoralis minor muscles [15][16]

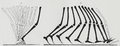

- Circumduction refers to a conical movement of a body part, such as a ball-and-socket joint or the eye. Circumduction is a combination of flexion, extension, adduction and abduction. Circumduction can be best performed at Ball and socket joints, such as the hip and shoulder, but may also be performed by other parts of the body such as fingers, hands, feet, and head.[17] A sporting example of circumduction occurs when performing a serve in tennis or bowling a cricket ball. "Windmilling" the arms or rotating the hand from the wrist are examples of circumductive movement.

- Opposition – A motion involving a grasping of the thumb and fingers.

- Reposition – To release an object by spreading the fingers and thumb.

- Reciprocal motion of a joint – Alternating motion in opposing directions, such as the elbow alternating between flexion and extension.

Rare or very specific terms

- Occlusion refers to motion of the mandibula towards the maxilla making contact between the teeth.[18]

- Reduction refers to a motion returning the spine or neck to its original state from a lateral movements (abduction), also classified as an adduction of the spine or neck.[19]

- Nutation and counternutation refer to movement of the sacrum defined by the rotation of the promontory downwards and anteriorly (nutation) or upwards and posteriorly (counternutation).[20] :333

- Protrusion and Retrusion are sometimes used to describe the anterior (protrusion) and posterior (retrusion) movement of the jaw.

Abnormal motion

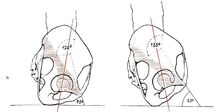

The prefix hyper- is sometimes added to describe movement beyond the normal limits to a limb's or organ's motion, such as in hyperflexion or hyperextension. Such movements are variously important; they may be used in surgery, such as in temporarily dislocating joints for surgical procedures, and also may be important in that they may seriously stress the joints involved. Such prefixes are common in Medical terminology. If a part of the body such as a joint is overstretched or "bent backwards" because of exaggerated extension motion, then one speaks of a hyperextension (as with the knee). This puts a lot of stress on the ligaments of the joint, and need not always be a voluntary movement, but may occur as part of accidents, falls, or other causes of trauma. Hyperextension is also sometimes defined as normal movement into the space posterior to the anatomical position.[21]

Movements of the human body

The following movements of bones constitute what movements are normally possible in various joints of the human body. Animals may have different degrees of movement; due to different position of joints, different muscles and different structures that block motion in the human body.

Certain movements are difficult to classify, such as movements of the carpal bones of the hand, or the tarsal bones of the foot, and are only really known by the orthopedic surgeon or hand surgeon specializing in their movements and not by ordinary medical practitioners.[citation needed]

| Movement | Muscles | Origin | Insertion |

|---|---|---|---|

| Flexion (150°–170°) |

Anterior fibers of deltoid | Clavicle | Middle of lateral surface of shaft of humerus |

| Clavicular part of pectoralis major | Clavicle | Lateral lip of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Long head of biceps brachii | Supraglenoid tubercle of scapula | Tuberosity of radius, Deep fascia of forearm | |

| Short head of biceps brachii | Coracoid process of scapula | ||

| Coracobrachialis | Coracoid process | Medial aspect of shaft of humerus | |

| Extension (40°) |

Posterior fibers of deltoid | Spine of scapula | Middle of lateral surface of shaft of humerus |

| Latissimus dorsi | Iliac crest, lumbar fascia, spines of lower six thoracic vertebrae, lower 3–4 ribs, inferior angle of scapula | Floor of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Teres major | Lateral border of scapula | Medial lip of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Abduction (160°–180°) |

Middle fibers of deltoid | Acromion process of scapula | Middle of lateral surface of shaft of humerus |

| Supraspinatus | Supraspinous fossa of scapula | Greater tuberosity of humerus | |

| Adduction (30°–40°) |

Sternal part of pectoralis major | Sternum, upper six costal cartilages | Lateral lip of bicipital groove of humerus |

| Latissimus dorsi | Iliac crest, lumbar fascia, spines of lower six thoracic vertebrae, lower 3-4 ribs, inferior angle of scapula | Floor of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Teres major | Lower third of lateral border of scapula | Medial lip of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Teres minor | Upper two thirds of lateral border of scapula | Greater tuberosity of humerus | |

| Lateral rotation (in abduction: 95°; in adduction: 70°) |

Infraspinatus | Infraspinous fossa of scapula | Greater tuberosity of humerus |

| Teres minor | Upper two thirds of lateral border of scapula | Greater tuberosity of humerus | |

| Posterior fibers of deltoid | Spine of scapula | Middle of lateral surface of shaft of humerus | |

| Medial rotation (in abduction: 40°–50°; in adduction: 70°) |

Subscapularis | Subscapular fossa | Lesser tuberosity of humerus |

| Latissimus dorsi | Iliac crest, lumbar fascia, spines of lower 3-4 ribs, inferior angle of scapula | Floor of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Teres major | Lower third of lateral border of scapula | Medial lip of bicipital groove of humerus | |

| Anterior fibers of deltoid | Clavicle | Middle of lateral surface of shaft of humerus |

Elbow

| Joint | From | To | Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| Humeroulnar joint | trochlear notch of the ulna | trochlea of humerus | Is a simple hinge-joint, and allows of movements of flexion and extension only. |

| Humeroradial joint | head of the radius | capitulum of the humerus | Is a ball-and-socket joint. |

| Superior radioulnar joint | head of the radius | radial notch of the ulna | In any position of flexion or extension, the radius, carrying the hand with it, can be rotated in it. This movement includes pronation and supination. |

Wrist and fingers

| Wrist & Midcarpals | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Adduction (Ulna Deviation) | Abduction (Radial Deviation) |

| Metacarpophalangeal(finger) | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Adduction | Abduction |

| Interphalangeal (finger) | Flexion | Extension |

| Carpometacarpal (thumb) | Flexion | Extension |

| Adduction | Abduction | |

| Opposition |

| Metacarpophalangeal (thumb) | Flexion | Extension |

| Adduction | Abduction |

| Interphalangeal (thumb) | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

Neck

| Neck (Atlantoccipital & Antlantoaxial) | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Lateral Flexion (Abduction) | Reduction (Adduction) | |

| Rotation |

Spine

| Cervical spine | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Lateral Flexion (Abduction) | Reduction (Adduction) | |

| Rotation |

| Thoracic spine | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Lateral Flexion (Abduction) | Reduction (Adduction) | |

| Rotation |

| Lumbar spine | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Lateral Flexion (Abduction) | Reduction (Adduction) | |

| Rotation |

| Hip (acetabulofemoral joint - art.coxae) | Flexion | Extension |

| Adduction | Abduction | |

| Transverse Adduction | Transverse Abduction | |

| Medial Rotation (Internal Rotation) | Lateral Rotation (External Rotation) |

| Knee - atriculatio genus | Flexion | Extension |

| Medial Rotation (Internal Rotation) | Lateral Rotation (External Rotation) |

| Ankle | Plantar Flexion | Dorsi Flexion |

Feet

| Intertarsal - (foot) | Inversion | Eversion |

| Plantarflexion |

| Metatarsophalangeal (toes) | Flexion | Extension / Hyperextension |

| Abduction | Adduction |

| Interphalangeal (toes) | Flexion | Extension |

Additional images

-

-

-

The leg extension as an isolated exercise.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Elaine N. Marieb, Particia Brady Wilhelm, Jon Mallat (2010). Human Anatomy. Pearson. ISBN 978-0-321-61611-1.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Lynn S. Lippert (2011). Clinical kinesiology and anatomy / Lynn S. Lippert. — 5th ed. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Company. pp. 6–7. ISBN 978-0-8036-2363-7.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 Swartz, Mark H. (2010). Textbook of physical diagnosis : history and examination (6th ed. ed.). Philadelphia, PA: Saunders/Elsevier. ISBN 978-1-4160-6203-5.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kyung Won, PhD. Chung (2005). Gross Anatomy (Board Review). Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-5309-0.

- ↑ Boone, Donna C.; Stanley P. Azen (July 1979). "Normal range of motion of joints in male subjects.". The Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery 61–A: 756–759. Retrieved 24 October 2012.

- ↑ American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (1965). Joint Motion: Method of Measuring and Recording. Chicago: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

- ↑ Roaas, Asbjørn; Gunnar B. J. Andersson (1982). "Normal Range of Motion of the Hip, Knee and Ankle Joints in Male Subjects, 30–40 Years of Age". Acta Orthopaedica 53 (2): 205–208. doi:10.3109/17453678208992202.

- ↑ Kendall FP, McCreary EK and Provance PG. (1993).Muscles Testing and Function. 4th Edition. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins. Philadelphia. ISBN 0-683-04576-8.

- ↑ Brukner P and Khan K. (1993). Clinical Sports Medicine. 1st Edition. McGraw-Hill Book Company. Sydney. ISBN 0-07-452852-1.

- ↑ "Foot in the bottom of the foot – RealHealthyNet". Realhealthynet.com. 2012-07-11. Retrieved 2013-08-30.

- ↑ Basic Human Anatomy, A Regional Study of Human Structure, Ronan O'Rahilly, M.D., Fabiola Müller, Dr. rer. nat., Stanley Carpenter, Ph.D., Rand Swenson, D.C., M.D., Ph.D. Copyright O'Rahilly 2008, Chapter 9: The Arm and Elbow

- ↑ Gross Anatomy: Functional Anatomy Of The Ankle And Foot. Accessed 18th December 2013

- ↑ shoulder/surface/scsurface4 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- ↑ Scapula & Clavicle Articulations

- ↑ shoulder/surface/scsurface3 at the Dartmouth Medical School's Department of Anatomy

- ↑ Animation at exrx.net

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. :Anatomy & Physiology The Unity of Form and Function, McGraw Hill 5th Edition. 2010. p. 300

- ↑ "The Occlusion". Retrieved November 15, 2013.

- ↑ "Spine Articulations". Retrieved November 18, 2013.

- ↑ Peggy A. Houglum, Dolores B. Bertoli (2012). Brunnstrom's Clinical Kinesiology. F.A. Davis Company. ISBN 978-0-8036-2352-1.

- ↑ Rod R Seeley, Trent D Stephens, Philip Tate. Anatomy & Physiology 4th Edition. WCB/McGraw-Hill, 1998 pg. 229 ISBN 0-697-41107-9

- ↑ Snell, Richard S. Clinical Anatomy by Systems. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 427–428.

- Saladin, K.S. 2010. Anatomy & Physiology: 5th edition. McGraw-Hill.

- Grants Atlas of Anatomy: 12th edition. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

External references

- White, T. D. & P. A. Folkens. Human Osteology. 1991. Academic Press, Inc. San Diego.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anatomical terms of motion. |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||