Capital punishment

| Part of a series on |

| Capital punishment |

|---|

| Issues |

|

Current use Italics indicate countries where capital punishment has not been used in the last ten years or that have a moratorium in effect |

|

| Past use |

|

| Current methods |

| Past methods |

| Civil death |

| Related topics |

| Execution, legal | |

|---|---|

| Intervention | |

| ICD-10-PCS | Y35.5 |

Capital punishment or the death penalty is a legal process whereby a person is put to death by the state as a punishment for a crime. The judicial decree that someone be punished in this manner is a death sentence, while the actual process of killing the person is an execution. Crimes that can result in a death penalty are known as capital crimes or capital offences. The term capital originates from the Latin capitalis, literally "regarding the head" (referring to execution by beheading).[2]

Capital punishment has, in the past, been practised by most societies, as a punishment for criminals, and political or religious dissidents. Historically, the carrying of the death sentence was often accompanied by torture, and executions were most often public.[3]

Currently 58 nations actively practise capital punishment, 98 countries have abolished it de jure for all crimes, 7 have abolished it for ordinary crimes only (maintain it for special circumstances such as war crimes), and 35 have abolished it de facto (have not used it for at least ten years and/or are under moratorium) .[4] Amnesty International considers most countries abolitionist, overall, the organisation considers 140 countries to be abolitionist in law or practice.[4] About 90% of all executions in the world take place in Asia.[5]

Nearly all countries in the world prohibit the execution of individuals who were under the age of 18 at the time of their crimes; since 2009, only Iran, Saudi Arabia, and Sudan have carried out such executions.[6] Executions of this kind are prohibited under international law.[7]

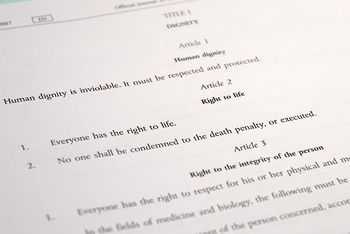

Capital punishment is a matter of active controversy in various countries and states, and positions can vary within a single political ideology or cultural region. In the European Union member states, Article 2 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union prohibits the use of capital punishment.[8] The Council of Europe, which has 47 member states, also prohibits the use of the death penalty by its members.

The United Nations General Assembly has adopted, in 2007, 2008 and 2010, non-binding resolutions calling for a global moratorium on executions, with a view to eventual abolition.[9] Although many nations have abolished capital punishment, over 60% of the world's population live in countries where executions take place, such as the People's Republic of China, India, the United States of America and Indonesia, the four most-populous countries in the world, which continue to apply the death penalty (although in India, Indonesia and in many US states it is rarely employed). Each of these four nations voted against the General Assembly resolutions.[10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18]

History

Execution of criminals and political opponents has been used by nearly all societies—both to punish crime and to suppress political dissent. In most places that practise capital punishment it is reserved for murder, espionage, treason, or as part of military justice. In some countries sexual crimes, such as rape, adultery, incest and sodomy, carry the death penalty, as do religious crimes such as apostasy in Islamic nations (the formal renunciation of the state religion). In many countries that use the death penalty, drug trafficking is also a capital offence. In China, human trafficking and serious cases of corruption are punished by the death penalty. In militaries around the world courts-martial have imposed death sentences for offences such as cowardice, desertion, insubordination, and mutiny.[19]

The use of formal execution extends to the beginning of recorded history. Most historical records and various primitive tribal practices indicate that the death penalty was a part of their justice system. Communal punishment for wrongdoing generally included compensation by the wrongdoer, corporal punishment, shunning, banishment and execution. Usually, compensation and shunning were enough as a form of justice.[20] The response to crime committed by neighbouring tribes or communities included formal apology, compensation or blood feuds.

A blood feud or vendetta occurs when arbitration between families or tribes fails or an arbitration system is non-existent. This form of justice was common before the emergence of an arbitration system based on state or organised religion. It may result from crime, land disputes or a code of honour. "Acts of retaliation underscore the ability of the social collective to defend itself and demonstrate to enemies (as well as potential allies) that injury to property, rights, or the person will not go unpunished."[21] However, in practice, it is often difficult to distinguish between a war of vendetta and one of conquest.

Severe historical penalties include breaking wheel, boiling to death, flaying, slow slicing, disembowelment, crucifixion, impalement, crushing (including crushing by elephant), stoning, execution by burning, dismemberment, sawing, decapitation, scaphism, necklacing or blowing from a gun.

Ancient history

Elaborations of tribal arbitration of feuds included peace settlements often done in a religious context and compensation system. Compensation was based on the principle of substitution which might include material (for example, cattle, slave) compensation, exchange of brides or grooms, or payment of the blood debt. Settlement rules could allow for animal blood to replace human blood, or transfers of property or blood money or in some case an offer of a person for execution. The person offered for execution did not have to be an original perpetrator of the crime because the system was based on tribes, not individuals. Blood feuds could be regulated at meetings, such as the Viking things.[22] Systems deriving from blood feuds may survive alongside more advanced legal systems or be given recognition by courts (for example, trial by combat). One of the more modern refinements of the blood feud is the duel.

In certain parts of the world, nations in the form of ancient republics, monarchies or tribal oligarchies emerged. These nations were often united by common linguistic, religious or family ties. Moreover, expansion of these nations often occurred by conquest of neighbouring tribes or nations. Consequently, various classes of royalty, nobility, various commoners and slave emerged. Accordingly, the systems of tribal arbitration were submerged into a more unified system of justice which formalised the relation between the different "classes" rather than "tribes". The earliest and most famous example is Code of Hammurabi which set the different punishment and compensation according to the different class/group of victims and perpetrators. The Torah (Jewish Law), also known as the Pentateuch (the first five books of the Christian Old Testament), lays down the death penalty for murder, kidnapping, magic, violation of the Sabbath, blasphemy, and a wide range of sexual crimes, although evidence suggests that actual executions were rare.[23]

A further example comes from Ancient Greece, where the Athenian legal system was first written down by Draco in about 621 BC: the death penalty was applied for a particularly wide range of crimes, though Solon later repealed Draco's code and published new laws, retaining only Draco's homicide statutes.[24] The word draconian derives from Draco's laws. The Romans also used death penalty for a wide range of offenses.[25][26]

Ancient Tang China

Although many are executed in China each year in the present day, there was a time in Tang Dynasty China when the death penalty was abolished.[27] This was in the year 747, enacted by Emperor Xuanzong of Tang (r. 712–756). When abolishing the death penalty Xuanzong ordered his officials to refer to the nearest regulation by analogy when sentencing those found guilty of crimes for which the prescribed punishment was execution. Thus depending on the severity of the crime a punishment of severe scourging with the thick rod or of exile to the remote Lingnan region might take the place of capital punishment. However the death penalty was restored only 12 years later in 759 in response to the An Lushan Rebellion.[28] At this time in China only the emperor had the authority to sentence criminals to execution. Under Xuanzong capital punishment was relatively infrequent, with only 24 executions in the year 730 and 58 executions in the year 736.[27]

.jpg)

The two most common forms of execution in China in the Tang period were strangulation and decapitation, which were the prescribed methods of execution for 144 and 89 offences respectively. Strangulation was the prescribed sentence for lodging an accusation against one's parents or grandparents with a magistrate, scheming to kidnap a person and sell them into slavery and opening a coffin while desecrating a tomb. Decapitation was the method of execution prescribed for more serious crimes such as treason and sedition. Interestingly, and despite the great discomfort involved, most Chinese during the Tang preferred strangulation to decapitation, as a result of the traditional Chinese belief that the body is a gift from the parents and that it is therefore disrespectful to one's ancestors to die without returning one's body to the grave intact.

Some further forms of capital punishment were practised in Tang China, of which the first two that follow at least were extralegal. The first of these was scourging to death with the thick rod which was common throughout the Tang especially in cases of gross corruption. The second was truncation, in which the convicted person was cut in two at the waist with a fodder knife and then left to bleed to death.[29] A further form of execution called Ling Chi (slow slicing), or death by/of a thousand cuts, was used in China from the close of the Tang dynasty (around 900) to its abolition in 1905.

When a minister of the fifth grade or above received a death sentence the emperor might grant him a special dispensation allowing him to commit suicide in lieu of execution. Even when this privilege was not granted, the law required that the condemned minister be provided with food and ale by his keepers and transported to the execution ground in a cart rather than having to walk there.

Nearly all executions under the Tang took place in public as a warning to the population. The heads of the executed were displayed on poles or spears. When local authorities decapitated a convicted criminal, the head was boxed and sent to the capital as proof of identity and that the execution had taken place.

Middle Ages

In medieval and early modern Europe, before the development of modern prison systems, the death penalty was also used as a generalised form of punishment. During the reign of Henry VIII, as many as 72,000 people are estimated to have been executed.[30]

Despite its wide use, calls for reform were not unknown. The 12th century Sephardic legal scholar, Moses Maimonides, wrote, "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent man to death." He argued that executing an accused criminal on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice". Maimonides' concern was maintaining popular respect for law, and he saw errors of commission as much more threatening than errors of omission.[31]

Islam on the whole accepts capital punishment,[32] and the Abbasid Caliphs in Baghdad, such as Al-Mu'tadid, were often cruel in their punishments.[33] Nevertheless, mercy is considered preferable in Islam[34] and in Sharia law the victim's family can choose to spare the life of the killer, which is not uncommon.[35] In the One Thousand and One Nights, also known as the Arabian Nights, the fictional storyteller Sheherazade is portrayed as being the "voice of sanity and mercy", with her philosophical position being generally opposed to punishment by death. She expresses this through several of her tales, including "The Merchant and the Jinni", "The Fisherman and the Jinni", "The Three Apples", and "The Hunchback".[36]

Modern era

The last several centuries have seen the emergence of modern nation-states. Almost fundamental to the concept of nation state is the idea of citizenship. This caused justice to be increasingly associated with equality and universality, which in Europe saw an emergence of the concept of natural rights. Another important aspect is that emergence of standing police forces and permanent penitential institutions. The death penalty became an increasingly unnecessary deterrent in prevention of minor crimes such as theft. The argument that deterrence, rather than retribution, is the main justification for punishment is a hallmark of the rational choice theory and can be traced to Cesare Beccaria whose well-known treatise On Crimes and Punishments (1764), condemned torture and the death penalty and Jeremy Bentham who twice critiqued the death penalty.[37] Moving executions there inside prisons and away from public view was prompted by official recognition of the phenomenon reported first by Beccaria in Italy and later by Charles Dickens and Karl Marx of increased violent criminality at the times and places of executions.

By 1820 in Britain, there were 160 crimes that were punishable by death, including crimes such as shoplifting, petty theft, stealing cattle, or cutting down trees in public place.[38] The severity of the so-called Bloody Code, however, was often tempered by juries who refused to convict, or judges, in the case of petty theft, who arbitrarily set the value stolen at below the statutory level for a capital crime.[39]

Contemporary era

The 20th century was a violent period. Tens of millions were killed in wars between nation-states as well as genocide perpetrated by nation states against political opponents (both perceived and actual), ethnic and religious minorities; the Turkish assault on the Armenians, Hitler's attempt to exterminate the European Jews, the Khmer Rouge decimation of Cambodia, the massacre of the Tutsis in Rwanda, to cite four of the most notorious examples. A large part of execution was summary execution of enemy combatants. In Nazi Germany there were three types of capital punishment; hanging, decapitation and death by shooting.[40] Also, modern military organisations employed capital punishment as a means of maintaining military discipline. The Soviets, for example, executed 158,000 soldiers for desertion during World War II.[41] In the past, cowardice, absence without leave, desertion, insubordination, looting, shirking under enemy fire and disobeying orders were often crimes punishable by death (see decimation and running the gauntlet). One method of execution since firearms came into common use has almost invariably been firing squad.

Various authoritarian states— for example those with fascist or communist governments—employed the death penalty as a potent means of political oppression. According to Robert Conquest, the leading expert on Stalin's purges, more than 1 million Soviet citizens were executed during the Great Terror of 1937–38, almost all by a bullet to the back of the head.[42] Mao Zedong publicly stated that "800,000" people had been executed after the Communist Party's victory in 1949. Partly as a response to such excesses, civil rights organizations have started to place increasing emphasis on the concept of human rights and abolition of the death penalty.

Among countries around the world, almost all European and many Pacific Area states (including Australia, New Zealand and Timor Leste), and Canada have abolished capital punishment. In Latin America, most states have completely abolished the use of capital punishment, while some countries, such as Brazil, allow for capital punishment only in exceptional situations, such as treason committed during wartime. The United States (the federal government and 32 of the states), Guatemala, most of the Caribbean and the majority of democracies in Asia (for example, Japan and India) and Africa (for example, Botswana and Zambia) retain it. South Africa's Constitutional Court, in judgement of the case of State v Makwanyane and Another, unanimously abolished the death penalty on 6 June 1995.[43][44]

Abolition was often adopted due to political change, as when countries shifted from authoritarianism to democracy, or when it became an entry condition for the European Union. The United States is a notable exception: some states have had bans on capital punishment for decades (the earliest is Michigan, where it was abolished in 1846), while others actively use it today. The death penalty there remains a contentious issue which is hotly debated.

In abolitionist countries, debate is sometimes revived by particularly brutal murders, though few countries have brought it back after abolishing it. However, a spike in serious, violent crimes, such as murders or terrorist attacks, has prompted some countries (such as Sri Lanka and Jamaica) to effectively end the moratorium on the death penalty. In retentionist countries, the debate is sometimes revived when a miscarriage of justice has occurred, though this tends to cause legislative efforts to improve the judicial process rather than to abolish the death penalty.

Movements towards "humane" execution

Trends in most of the world have long been to move to less painful, or more humane, executions. France developed the guillotine for this reason in the final years of the 18th century, while Britain banned drawing and quartering in the early 19th century. Hanging by turning the victim off a ladder or by kicking a stool or a bucket, which causes death by suffocation, was replaced by long drop "hanging" where the subject is dropped a longer distance to dislocate the neck and sever the spinal cord. Shah of Persia introduced throat-cutting and blowing from a gun as quick and painless alternatives to more tormentous methods of executions used at that time.[45] In the U.S., the electric chair and the gas chamber were introduced as more humane alternatives to hanging, but have been almost entirely superseded by lethal injection, which in turn has been criticised as being too painful. Nevertheless, some countries still employ slow hanging methods, beheading by sword and even stoning, although the latter is rarely employed.

In early New England, public executions were a very solemn and sorrowful occasion, sometimes attended by large crowds, who also listened to a Gospel message[46] and remarks by local preachers and politicians. The Connecticut Courant records one such public execution on 1 December 1803, saying, "The assembly conducted through the whole in a very orderly and solemn manner, so much so, as to occasion an observing gentleman acquainted with other countries as well as this, to say that such an assembly, so decent and solemn, could not be collected anywhere but in New England."[47]

Abolitionism

The death penalty was banned in China between 747 and 759. In Japan, Emperor Saga abolished the death penalty in 818 under the influence of Shinto and it lasted until 1156. Therefore, capital punishment was not employed for 338 years in ancient Japan.[48]

In England, a public statement of opposition was included in The Twelve Conclusions of the Lollards, written in 1395. Sir Thomas More's Utopia, published in 1516, debated the benefits of the death penalty in dialogue form, coming to no firm conclusion. More recent opposition to the death penalty stemmed from the book of the Italian Cesare Beccaria Dei Delitti e Delle Pene ("On Crimes and Punishments"), published in 1764. In this book, Beccaria aimed to demonstrate not only the injustice, but even the futility from the point of view of social welfare, of torture and the death penalty. Influenced by the book, Grand Duke Leopold II of Habsburg, famous enlightened monarch and future Emperor of Austria, abolished the death penalty in the then-independent Grand Duchy of Tuscany, the first permanent abolition in modern times. On 30 November 1786, after having de facto blocked capital executions (the last was in 1769), Leopold promulgated the reform of the penal code that abolished the death penalty and ordered the destruction of all the instruments for capital execution in his land. In 2000 Tuscany's regional authorities instituted an annual holiday on 30 November to commemorate the event. The event is commemorated on this day by 300 cities around the world celebrating Cities for Life Day.

The Roman Republic banned capital punishment in 1849. Venezuela followed suit and abolished the death penalty in 1854[49] and San Marino did so in 1865. The last execution in San Marino had taken place in 1468. In Portugal, after legislative proposals in 1852 and 1863, the death penalty was abolished in 1867.

Abolition occurred in Canada in 1976, in France in 1981, and in Australia in 1973 (although the state of Western Australia retained the penalty until 1984). In 1977, the United Nations General Assembly affirmed in a formal resolution that throughout the world, it is desirable to "progressively restrict the number of offenses for which the death penalty might be imposed, with a view to the desirability of abolishing this punishment".[50]

In the United Kingdom, it was abolished for murder (leaving only treason, piracy with violence, arson in royal dockyards and a number of wartime military offences as capital crimes) for a five-year experiment in 1965 and permanently in 1969, the last execution having taken place in 1964. It was abolished for all peacetime offences in 1998.[51]

In the United States, Michigan was the first state to ban the death penalty, on 18 May 1846.[52] The death penalty was declared unconstitutional between 1972 and 1976 based on the Furman v. Georgia case, but the 1976 Gregg v. Georgia case once again permitted the death penalty under certain circumstances. Further limitations were placed on the death penalty in Atkins v. Virginia (death penalty unconstitutional for persons suffering from mental retardation) and Roper v. Simmons (death penalty unconstitutional if defendant was under age 18 at the time the crime was committed). Currently, as of 2 May 2013, 18 states of the U.S. and the District of Columbia ban capital punishment, with Maryland the most recent state to ban the practice.[53] A 2010 Gallup poll shows that 64% of Americans support the death penalty for someone convicted of murder, down from 65% in 2006 and 68% in 2001.[54][55] Of the states where the death penalty is permitted, California has the largest number of inmates on death row. Texas has performed the most executions (since the US Supreme Court allowed capital punishment to resume in 1976, 40% of all US executions have taken place in Texas),[56] and Oklahoma has had (through mid-2011) the highest per capita execution rate.[57]

One of the latest countries to abolish the death penalty for all crimes was Gabon, in February 2010.[58]

Human rights activists oppose the death penalty, calling it "cruel, inhuman, and degrading punishment". Amnesty International considers it to be "the ultimate denial of Human Rights".[59]

Contemporary use

Global distribution

Since World War II there has been a trend toward abolishing the death penalty. In 1977, 16 countries were abolitionist. According to information published by Amnesty International in 2012, 97 countries had abolished capital punishment altogether, 8 had done so for all offences except under special circumstances, and 36 had not used it for at least 10 years or were under a moratorium. The other 57 retained the death penalty in active use.[60]

| Criminal procedure |

|---|

| Criminal trials and convictions |

| Rights of the accused |

| Verdict |

| Sentencing |

| Post-sentencing |

|

| Related areas of law |

|

| Portals |

|

|

According to Amnesty International, only 21 countries were known to have had executions carried out in 2011. In addition, there are countries which do not publish information on the use of capital punishment, most significantly China.[61] At least 18,750 people worldwide were under sentence of death at the beginning of 2012.[62]

| Rank | Country | Number executed in 2011[63] |

|---|---|---|

| 1 |

People's Republic of China | Officially not released.[64][65] |

| 2 |

Iran | 360+ |

| 3 |

Saudi Arabia | 82+ |

| 4 |

Iraq | 68+ |

| 5 |

United States | 43 |

| 6 |

Yemen | 41+ |

| 7 |

North Korea | 30+ |

| 8 |

Somalia | 10 |

| 9 |

Sudan | 7+ |

| 10 |

Bangladesh | 5+ |

| 11 |

Vietnam | 5+ |

| 12 |

South Sudan | 5 |

| 13 |

Republic of China (Taiwan) | 5 |

| 14 |

Singapore | 4[66] |

| 15 |

Palestinian Authority | 3 |

| 16 |

Afghanistan | 2 |

| 17 |

Belarus | 2 |

| 18 |

Egypt | 1+ |

| 19 |

United Arab Emirates | 1 |

| 20 |

Malaysia | + |

| 21 |

Syria | + |

The use of the death penalty is becoming increasingly restrained in some retentionist countries including Taiwan and Singapore.[67] Indonesia carried out no executions between November 2008 and March 2013.[68] Japan and 32 out of 50 states in the United States are the only OECD members that are classified by Amnesty International as 'retentionist' (South Korea is classified as 'abolitionist in practice').[1] Nearly all of retentionist countries are situated in Asia, Africa and the Caribbean.[1] The only retentionist country in Europe is Belarus. The death penalty was overwhelmingly practised in poor and authoritarian states, which often employed the death penalty as a tool of political oppression. During the 1980s, the democratisation of Latin America swelled the rank of abolitionist countries.

This was soon followed by the fall of communism in Europe. Many of the countries which restored democracy aspired to enter the EU. The European Union and the Council of Europe both strictly require member states not to practise the death penalty (see Capital punishment in Europe). Public support for the death penalty in the EU varies.[69] The last execution on the present day territory of the Council of Europe has taken place in 1997 in Ukraine.[70][71]On the other hand, rapid industrialisation in Asia has been increasing the number of developed retentionist countries. In these countries, the death penalty enjoys strong public support, and the matter receives little attention from the government or the media; in China there is a small but growing movement to abolish the death penalty altogether.[72] This trend has been followed by some African and Middle Eastern countries where support for the death penalty is high.

Some countries have resumed practicing the death penalty after having suspended executions for long periods. The United States suspended executions in 1972 but resumed them in 1976, then again on 25 September 2007 to 16 April 2008; there was no execution in India between 1995 and 2004; and Sri Lanka declared an end to its moratorium on the death penalty on 20 November 2004,[73] although it has not yet performed any executions. The Philippines re-introduced the death penalty in 1993 after abolishing it in 1987, but abolished it again in 2006.

In May 2013, Papua New Guinea lawmakers voted to introduce the death penalty for crimes such as rape, robbery and sorcery-related murder, and introduce punishments such as electrocution, firing squad and suffocation.[citation needed]

In 2011, the USA was the only source of executions (43) in the G8 countries or Western Hemisphere.[74] The latest country to move towards abolition is Mongolia. In January 2012, its Parliament adopted a bill providing for the death penalty to be abolished.[75]

For further information about capital punishment in individual countries or regions, see: Australia · Canada · People's Republic of China (excluding Hong Kong and Macau) · Europe · India · Iran · Iraq · Japan · New Zealand ·Pakistan· Philippines · Russia · Singapore · Taiwan · United Kingdom · United States

Execution for drug-related offences

Some countries that retain the death penalty for murder and other violent crimes do not execute offenders for drug-related crimes. Countries that have statutory provisions for the death penalty for drug-related offences as of 2012 include:

Afghanistan

Afghanistan Bangladesh

Bangladesh Brunei#

Brunei# People's Republic of China[76]

People's Republic of China[76] Republic of China[77] Also available on Chinese Wikisource.

Republic of China[77] Also available on Chinese Wikisource. Cuba#

Cuba# Egypt

Egypt Indonesia

Indonesia Iran

Iran Iraq

Iraq Kuwait

Kuwait Laos#

Laos# Malaysia

Malaysia Oman

Oman Pakistan

Pakistan Saudi Arabia

Saudi Arabia Singapore

Singapore Somalia

Somalia Sri Lanka#

Sri Lanka# Thailand

Thailand Vietnam

Vietnam United Arab Emirates

United Arab Emirates United States[78]

United States[78] Yemen

Yemen Zimbabwe#

Zimbabwe#

- Notes

- (#) The capital punishment was not used in the last 10 years (or has a moratorium in effect)

Juvenile offenders

The death penalty for juvenile offenders (criminals aged under 18 years at the time of their crime) has become increasingly rare. Considering the Age of Majority is still not 18 in some countries, since 1990 nine countries have executed offenders who were juveniles at the time of their crimes: The People's Republic of China (PRC), Democratic Republic of the Congo, Iran, Nigeria, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, the United States (see List of juvenile offenders executed in the United States), and Yemen.[79] The PRC, Pakistan, the United States, Yemen and Iran have since raised the minimum age to 18.[80][81] Amnesty International has recorded 61 verified executions since then, in several countries, of both juveniles and adults who had been convicted of committing their offenses as juveniles.[82] The PRC does not allow for the execution of those under 18, but child executions have reportedly taken place.[83]

Starting in 1642 within British America, an estimated 365[84] juvenile offenders were executed by the states and federal government of the United States.[85] The United States Supreme Court abolished capital punishment for offenders under the age of 16 in Thompson v. Oklahoma (1988), and for all juveniles in Roper v. Simmons (2005). In addition, in 2002, the United States Supreme Court declared unconstitutional the execution of individuals with mental retardation, in Atkins v. Virginia.[86]

Between 2005 and May 2008, Iran, Pakistan, Saudi Arabia, Sudan and Yemen were reported to have executed child offenders, the most being from Iran.[87]

The United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child, which forbids capital punishment for juveniles under article 37(a), has been signed by all countries and ratified, except for Somalia and the United States (notwithstanding the latter's Supreme Court decisions abolishing the practice).[88] The UN Sub-Commission on the Promotion and Protection of Human Rights maintains that the death penalty for juveniles has become contrary to a jus cogens of customary international law. A majority of countries are also party to the U.N. International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (whose Article 6.5 also states that "Sentence of death shall not be imposed for crimes committed by persons below eighteen years of age...").

In Japan, the minimum age for the death penalty is 18 as mandated by the internationals standards. But under Japanese law, anyone under 20 is considered a juvenile. There are three men currently on death row for crimes they committed at age 18 or 19.

Iran

Iran, despite its ratification of the Convention on the Rights of the Child and International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, was the world's biggest executioner of juvenile offenders, for which it has received international condemnation; the country's record is the focus of the Stop Child Executions Campaign. But on 10 February 2012 Iran's parliament changed the controversial law of executing juveniles. In the new law, the age of 18 (solar year) would be for both genders considered and juvenile offenders will be sentenced on a separate law than of adults.[80][81] Based on the Islamic law which now seems to have been revised, girls at the age of 9 and boys at 15 of lunar year (11 days shorter than a solar year) were fully responsible for their crimes.[80]

Iran accounted for two-thirds of the global total of such executions, and currently has roughly 140 people on death row for crimes committed as juveniles (up from 71 in 2007).[89][90] The past executions of Mahmoud Asgari, Ayaz Marhoni and Makwan Moloudzadeh became international symbols of Iran's child capital punishment and the judicial system that hands down such sentences.[91][92]

Saudi Arabia

.jpg)

Saudi Arabia executes criminals who were minors at the time of the offense.[93][94] In 2013, Saudi Arabia was the center of an international controversy after it executed Rizana Nafeek, a Sri Lankan domestic worker, who was believed to have been 17 years old at the time of the crime.[95]

Somalia

There is evidence that child executions are taking place in the parts of Somalia controlled by the Islamic Courts Union (ICU). In October 2008, a girl, Aisho Ibrahim Dhuhulow was buried up to her neck at a football stadium, then stoned to death in front of more than 1,000 people. The stoning occurred after she had allegedly pleaded guilty to adultery in a shariah court in Kismayo, a city controlled by the ICU. According to a local leader associated with the ICU, she had stated that she wanted shariah law to apply.[96] However, other sources state that the victim had been crying, that she begged for mercy and had to be forced into the hole before being buried up to her neck in the ground.[97] Amnesty International later learned that the girl was in fact 13 years old and had been arrested by the al-Shabab militia after she had reported being gang-raped by three men.[98]

Somalia's established Transitional Federal Government announced in November 2009 (reiterated in 2013)[99] that it plans to ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child. This move was lauded by UNICEF as a welcome attempt to secure children's rights in the country.[100]

Methods

The following methods of execution permitted for use in 2010:[101][102][103][104][105]

- Beheading (Saudi Arabia, Qatar)

- Electric chair (as an option in Alabama, Tennessee, Virginia, South Carolina, Florida, Oklahoma and Kentucky in the USA)

- Gas chamber (California, Missouri and Arizona in the USA)

- Hanging (Afghanistan, Iran, Iraq, Japan, Mongolia, Malaysia, Pakistan, Palestinian National Authority, Lebanon, Yemen, Egypt, India, Myanmar, Singapore, Sri Lanka, Syria, Zimbabwe, South Korea, Malawi, Liberia, Chad, Washington in the USA)

- Lethal injection (Guatemala, Thailand, the People's Republic of China, Vietnam, all states in the USA that are using capital punishment)

- Shooting (the People's Republic of China, Republic of China, Vietnam, Belarus, Lebanon, Cuba, Grenada, North Korea, Indonesia, Yemen and Oklahoma in the USA)

Controversy and debate

There are many organizations worldwide, such as Amnesty International, and country-specific, such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), that have abolition of the death penalty as a fundamental purpose.[106][107]

Advocates of the death penalty argue that it deters crime, is a good tool for police and prosecutors (in plea bargaining for example),[108] makes sure that convicted criminals do not offend again and is a just penalty for atrocious crimes such as child murders, serial killers or torture murderers.[109] Opponents of capital punishment argue that not all people affected by murder desire a death penalty, that execution discriminates against minorities and the poor, and that it encourages a "culture of violence" and that it violates human rights.[110]

Human rights

Abolitionists believe capital punishment is the worst violation of human rights, because the right to life is the most important, and judicial execution violates it without necessity and inflicts to the condemned a psychological torture. Albert Camus wrote in a 1956 book called Reflections on the Guillotine, Resistance, Rebellion & Death:

An execution is not simply death. It is just as different from the privation of life as a concentration camp is from prison. [...] For there to be an equivalency, the death penalty would have to punish a criminal who had warned his victim of the date at which he would inflict a horrible death on him and who, from that moment onward, had confined him at his mercy for months. Such a monster is not encountered in private life.[111]

In the classic doctrine of natural rights as expounded by for instance Locke and Blackstone, on the other hand, it is an important idea that the right to life can be forfeited.[112]

Wrongful execution

It is frequently argued that capital punishment leads to miscarriage of justice through the wrongful execution of innocent persons.[113] Many people have been proclaimed innocent victims of the death penalty.[114][115][116]

Some have claimed that as many as 39 executions have been carried out in the face of compelling evidence of innocence or serious doubt about guilt from in the US from 1992 through 2004. Newly available DNA evidence prevented the pending execution of more than 15 death row inmates during the same period in the US,[117] but DNA evidence is only available in a fraction of capital cases.[118] However, since the death penalty reinstatement in the United States during the 1970s, no inmate executed has been granted posthumous pardon.[119]

Also improper procedure may result in unfair executions. For example, Amnesty International argues that in Singapore "the Misuse of Drugs Act contains a series of presumptions which shift the burden of proof from the prosecution to the accused. This conflicts with the universally guaranteed right to be presumed innocent until proven guilty".[120] This refers to a situation when someone is being caught with drugs. In this situation, in almost any jurisdiction, the prosecution has a prima facie case.

Retribution

Supporters of the death penalty argued that death penalty is morally justified when applied in murder especially with aggravating elements such as multiple homicide, child murder, torture murder and mass killing such as terrorism, massacre, or genocide. Some even argue that not applying death penalty in latter cases is patently unjust. This argument is strongly defended by New York law professor Robert Blecker,[121] who says that the punishment must be painful in proportion to the crime. It would be unfair that those who have committed these horrible crimes stay alive, even incarcerated.

Abolitionists argue that retribution is simply revenge and cannot be condoned. Others while accepting retribution as an element of criminal justice nonetheless argue that life without parole is a sufficient substitute. It is also argued that the punishing of a killing with another killing is a relatively unique punishment for a violent act, because in general violent crimes are not punished by subjecting the perpetrator to a similar act (e.g. rapists are not punished by being sexually assaulted).[122]

Racial, ethic and social class bias

Opponents of the death penalty argue that this punishment is being used more often against perpetrators from racial and ethnic minorities and from lower socioeconomic backgrounds, than against those criminals who come from a privileged background; and that the background of the victim also influences the outcome.[123][124][125]

International views

The United Nations introduced a resolution during the General Assembly's 62nd sessions in 2007 calling for a universal ban.[126][127] The approval of a draft resolution by the Assembly's third committee, which deals with human rights issues, voted 99 to 52, with 33 abstentions, in favour of the resolution on 15 November 2007 and was put to a vote in the Assembly on 18 December.[128][129][130]

Again in 2008, a large majority of states from all regions adopted a second resolution calling for a moratorium on the use of the death penalty in the UN General Assembly (Third Committee) on 20 November. 105 countries voted in favour of the draft resolution, 48 voted against and 31 abstained.

A range of amendments proposed by a small minority of pro-death penalty countries were overwhelmingly defeated. It had in 2007 passed a non-binding resolution (by 104 to 54, with 29 abstentions) by asking its member states for "a moratorium on executions with a view to abolishing the death penalty".[131]

A number of regional conventions prohibit the death penalty, most notably, the Sixth Protocol (abolition in time of peace) and the 13th Protocol (abolition in all circumstances) to the European Convention on Human Rights. The same is also stated under the Second Protocol in the American Convention on Human Rights, which, however has not been ratified by all countries in the Americas, most notably Canada and the United States. Most relevant operative international treaties do not require its prohibition for cases of serious crime, most notably, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. This instead has, in common with several other treaties, an optional protocol prohibiting capital punishment and promoting its wider abolition.[132]

Several international organizations have made the abolition of the death penalty (during time of peace) a requirement of membership, most notably the European Union (EU) and the Council of Europe. The EU and the Council of Europe are willing to accept a moratorium as an interim measure. Thus, while Russia is a member of the Council of Europe, and the death penalty remains codified in its law, it has not made use of it since becoming a member of the Council - Russia has not executed anyone since 1996. With the exception of Russia (abolitionist in practice), Kazakhstan (abolitionist for ordinary crimes only), and Belarus (retentionist), all European countries are classified as abolitionist.[1]

Latvia abolished de jure the death penalty for war crimes in 2012, becoming the last EU member to do so.[133]

The Protocol no.13 calls for the abolition of the death penalty in all circumstances (including for war crimes). The majority of European countries have signed and ratified it. Some European countries have not done this, but all of them except Belarus and Kazakhstan have now abolished the death penalty in all circumstances (de jure, and Russia de facto). Poland is the most recent country to ratify the protocol, on 28 August 2013.[134]

The Protocol no.6 which prohibits the death penalty during peacetime has been ratified by all members of the European Council, except Russia (which has signed, but not ratified).

There are also other international abolitionist instruments, such as the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, which has 78 parties[135]; and the Protocol to the American Convention on Human Rights to Abolish the Death Penalty (for the Americas; ratified by 13 states).[136]

Turkey has recently, as a move towards EU membership, undergone a reform of its legal system. Previously there was a de facto moratorium on the death penalty in Turkey as the last execution took place in 1984. The death penalty was removed from peacetime law in August 2002, and in May 2004 Turkey amended its constitution in order to remove capital punishment in all circumstances. It ratified Protocol no. 13 to the European Convention on Human Rights in February 2006. As a result, Europe is a continent free of the death penalty in practice, all states but Russia, which has entered a moratorium, having ratified the Sixth Protocol to the European Convention on Human Rights, with the sole exception of Belarus, which is not a member of the Council of Europe. The Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe has been lobbying for Council of Europe observer states who practise the death penalty, the U.S. and Japan, to abolish it or lose their observer status. In addition to banning capital punishment for EU member states, the EU has also banned detainee transfers in cases where the receiving party may seek the death penalty.[137]

Sub Saharan African countries which have recently abolished the death penalty include Burundi, which abolished the death penalty for all crimes in 2009,[138] and Gabon which did the same in 2010.[139] On 5 July 2012, Benin has become part of the Second Optional Protocol to the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), which prohibits the use of the death penalty.[140]

The newly created South Sudan is among the 111 UN member states that supported the resolution passed by the United Nations General Assembly that called for the removal of the death penalty, therefore affirming its opposition to the practice. South Sudan, however, has not yet abolished the death penalty and stated that it must first amend its Constitution, and until that happens it will continue to use the death penalty.[141]

Among non-governmental organizations (NGOs), Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch are noted for their opposition to capital punishment. A number of such NGOs, as well as trade unions, local councils and bar associations formed a World Coalition Against the Death Penalty in 2002.

Religious views

The world's major religions have mixed opinions on the death penalty, depending on the sect, the individual believer, and the time period.

Buddhism

There is disagreement among Buddhists as to whether or not Buddhism forbids the death penalty. The first of the Five Precepts (Panca-sila) is to abstain from destruction of life. Chapter 10 of the Dhammapada states:

"Everyone fears punishment; everyone fears death, just as you do. Therefore you do not kill or cause to be killed."[142]

Chapter 26, the final chapter of the Dhammapada, states, "Him I call a brahmin who has put aside weapons and renounced violence toward all creatures. He neither kills nor helps others to kill." These sentences are interpreted by many Buddhists (especially in the West) as an injunction against supporting any legal measure which might lead to the death penalty. However, as is often the case with the interpretation of scripture, there is dispute on this matter. Historically, most states where the official religion is Buddhism have imposed capital punishment for some offenses. One notable exception is the abolition of the death penalty by the Emperor Saga of Japan in 818. This lasted until 1165, although in private manors executions continued to be conducted as a form of retaliation. Japan still imposes the death penalty, although some recent justice ministers have refused to sign death warrants, citing their Buddhist beliefs as their reason.[143] Other Buddhist-majority states vary in their policy. For example, Bhutan has abolished the death penalty, but Thailand still retains it, although Buddhism is the official religion in both. Mongolia abolished the death penalty in 2012.

Many stories in Buddhist scripture stress the superior power of the Buddha's teaching to rehabilitate murderers and other criminals. The most well-known example is Angulimala in the Theravadan Pali canon who had killed 999 people and then attempted to kill his own mother and the Buddha, but under the influence of the Buddha he repented and entered the monkhood. The Buddha succeeded when the King and all his soldiers failed to eliminate the murderer by force.[144]

.jpg)

Without one official teaching on the death penalty, Thai monks are typically divided on the issue with some favoring abolition of the death penalty while others see it as bad karma stemming from bad actions in the past. [145]

In the edicts of the great Buddhist king Ashoka (ca. 304–232 BC) inscribed on great pillars around his kingdom, the King showed reverence for all life by giving up the slaughtering of animals and many of his subjects followed his example. King Ashoka also extended the period before execution of those condemned to death so they could make a final appeal for their lives.

A close reading of texts in the Pali canon reveals different attitudes towards violence and capital punishment. The Pali scholar Steven Collins finds Dhamma in the Pali canon divided into two categories according to the attitude taken towards violence. In Mode 1 Dhamma the use of violence is "context-dependent and negotiable". A King should not pass judgement in haste or anger but the punishment should fit the crime, with warfare and capital punishment acceptable in certain situations. In Mode 2 Dhamma the use of violence is "context-independent and non-negotiable" and the only advice to kings is to abdicate, renounce the world and leave everything to the law of karma. Buddhism is incompatible with any form of violence especially warfare and capital punishment. [146]

In the world that humans inhabit there is a continual tension between these two modes of Dhamma. This tension is best exhibited in the Cakkavatti Sihanada Sutta (Digha Nikaya 26 of the Sutta Pitaka of the Pāli Canon), the story of humanity's decline from a golden age in the past. A critical turning point comes when the King decides not to give money to a man who has committed theft but instead to cut off his head and also to carry out this punishment in a particularly cruel and humiliating manner, parading him in public to the sound of drums as he is taken to the execution ground outside the city. In the wake of this decision by the king, thieves take to imitating the King's actions and murder the people from whom they steal to avoid detection. Thieves turn to highway robbery and attacking small villages and towns far away from the royal capital where they won't be detected. A downwards spiral towards social disorder and chaos has begun. [147]

Christianity

Views on the death penalty in Christianity run a spectrum of opinions, from complete condemnation of the punishment, seeing it as a form of revenge and as contrary to Christ's message of forgiveness, to enthusiastic support based primarily on Old Testament law.

Among the teachings of Jesus Christ in the Gospel of Luke and the Gospel of Matthew, the message to his followers that one should "Turn the other cheek" and his example in the story Pericope Adulterae, in which Jesus intervenes in the stoning of an adulteress, are generally accepted as his condemnation of physical retaliation (though most scholars[148][149] agree that the latter passage was "certainly not part of the original text of St John's Gospel"[150]) More militant Christians consider Romans 13:3–4 to support the death penalty. Many Christians have believed that Jesus' doctrine of peace speaks only to personal ethics and is distinct from civil government's duty to punish crime.

In the Old Testament, Leviticus Leviticus 20:2–27 provides a list of transgressions in which execution is recommended. Christian positions on these passages vary.[151] The sixth commandment (fifth in the Roman Catholic and Lutheran churches) is translated as "Thou shalt not kill" by some denominations and as "Thou shalt not murder" by others. As some denominations do not have a hard-line stance on the subject, Christians of such denominations are free to make a personal decision.[152]

Eastern Orthodox Christianity does not officially condemn or endorse capital punishment. It states that it is not a totally objectionable thing, but also that its abolishment can be driven by genuine Christian values, especially stressing the need for mercy.[153]

The Rosicrucian Fellowship and many other Christian esoteric schools condemn capital punishment in all circumstances.[154][155]

Roman Catholic Church

St. Thomas Aquinas, a Doctor of the Church, accepted the death penalty as a deterrent and prevention method but not as a means of vengeance. (See Aquinas on the death penalty.) The Roman Catechism stated this teaching thus:

Another kind of lawful slaying belongs to the civil authorities, to whom is entrusted power of life and death, by the legal and judicious exercise of which they punish the guilty and protect the innocent. The just use of this power, far from involving the crime of murder, is an act of paramount obedience to this Commandment which prohibits murder. The end of the Commandment is the preservation and security of human life. Now the punishments inflicted by the civil authority, which is the legitimate avenger of crime, naturally tend to this end, since they give security to life by repressing outrage and violence. Hence these words of David: In the morning I put to death all the wicked of the land, that I might cut off all the workers of iniquity from the city of the Lord.[156]

In Evangelium Vitae, Pope John Paul II suggested that capital punishment should be avoided unless it is the only way to defend society from the offender in question, opining that punishment "ought not go to the extreme of executing the offender except in cases of absolute necessity: in other words, when it would not be possible otherwise to defend society. Today however, as a result of steady improvements in the organization of the penal system, such cases are very rare, if not practically non-existent."[157] The most recent edition of the Catechism of the Catholic Church restates this view.[158] That the assessment of the contemporary situation advanced by John Paul II is not binding on the faithful was confirmed by Cardinal Ratzinger when he wrote in 2004 that,

if a Catholic were to be at odds with the Holy Father on the application of capital punishment or on the decision to wage war, he would not for that reason be considered unworthy to present himself to receive Holy Communion. While the Church exhorts civil authorities to seek peace, not war, and to exercise discretion and mercy in imposing punishment on criminals, it may still be permissible to take up arms to repel an aggressor or to have recourse to capital punishment. There may be a legitimate diversity of opinion even among Catholics about waging war and applying the death penalty, but not however with regard to abortion and euthanasia.[159]

The 1911 edition of the Catholic Encyclopedia suggested that Catholics must hold that "the infliction of capital punishment is not contrary to the teaching of the Catholic Church, and the power of the State to visit upon culprits the penalty of death derives much authority from revelation and from the writings of theologians", but that the matter of "the advisability of exercising that power is, of course, an affair to be determined upon other and various considerations."[160]

Protestants

The Religious Society of Friends or Quaker Church is one of the earliest American opponents of capital punishment and unequivocally opposes execution in all its forms.

Southern Baptists support the fair and equitable use of capital punishment for those guilty of murder or treasonous acts, so long as it does not constitute as an act of personal revenge or discrimination.[161]

The Lambeth Conference of Anglican bishops condemned the death penalty in 1988:

This Conference: ... 3. Urges the Church to speak out against: ... (b) all governments who practise capital punishment, and encourages them to find alternative ways of sentencing offenders so that the divine dignity of every human being is respected and yet justice is pursued;....[162]

The United Methodist Church, along with other Methodist churches, also condemns capital punishment, saying that it cannot accept retribution or social vengeance as a reason for taking human life.[163] The Church also holds that the death penalty falls unfairly and unequally upon marginalised persons including the poor, the uneducated, ethnic and religious minorities, and persons with mental and emotional illnesses.[164] The General Conference of the United Methodist Church calls for its bishops to uphold opposition to capital punishment and for governments to enact an immediate moratorium on carrying out the death penalty sentence.

In a 1991 social policy statement, the ELCA officially took a stand to oppose the death penalty. It states that revenge is a primary motivation for capital punishment policy and that true healing can only take place through repentance and forgiveness.[165]

Community of Christ, the former Reorganized Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (RLDS), is opposed to capital punishment. The first stand against capital punishment was taken by the church's Presiding High Council in 1995. This was followed by a resolution of the World Conference in 2000. This resolution, WC 1273, states:[W]e stand in opposition to the use of the death penalty; and ... as a peace church we seek ways to achieve healing and restorative justice. Church members are encouraged to work for the abolition of the death penalty in those states and nations that still practise this form of punishment.[166]

Several key leaders early in the Protestant Reformation, including Martin Luther and John Calvin, followed the traditional reasoning in favour of capital punishment, and the Lutheran Church's Augsburg Confession explicitly defended it. Some Protestant groups have cited Genesis 9:5–6, Romans 13:3–4, and Leviticus 20:1–27 as the basis for permitting the death penalty.[167]

Mennonites, Church of the Brethren and Friends have opposed the death penalty since their founding, and continue to be strongly opposed to it today. These groups, along with other Christians opposed to capital punishment, have cited Christ's Sermon on the Mount (transcribed in Matthew Chapter 5–7) and Sermon on the Plain (transcribed in Luke 6:17–49). In both sermons, Christ tells his followers to turn the other cheek and to love their enemies, which these groups believe mandates nonviolence, including opposition to the death penalty.

Mormonism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also called Mormons) neither promotes nor opposes capital punishment, although the church's founder, Joseph Smith, Jr., supported it.[168] However, today the church officially states that it is a "matter to be decided solely by the prescribed processes of civil law."[169]

Hinduism

A basis can be found in Hindu teachings both for permitting and forbidding the death penalty. Hinduism preaches ahimsa (or ahinsa, non-violence), but also teaches that the soul cannot be killed and death is limited only to the physical body. The soul is reborn into another body upon death (until Moksha), akin to a human changing clothes. The religious, civil and criminal law of Hindus is encoded in the Dharmaśāstras and the Arthasastra. The Dharmasastras describe many crimes and their punishments and call for the death penalty in several instances, including murder and righteous warfare.[170]

Islam

Some forms of Islamic law, as in Saudi Arabia, may require capital punishment, but there is great variation within Islamic nations as to actual capital punishment. Apostasy in Islam and stoning to death in Islam are controversial topics. Furthermore, as expressed in the Qur'an, capital punishment is condoned. Instead, murder is treated as a civil crime and is covered by the law of retaliation, whereby the relatives of the victim decide whether the offender is punished with death by the authorities or made to pay diyah as compensation.[25] Muslims frequently refer to the story of Cain and Abel when referring to killing someone. The Qur'an says the following:

- "If anyone kills person– unless it be (a punishment) for murder or for spreading mischief in the land— it would be as if he killed all people. And if anyone saves a life, it would be as if he saved the life of all people" (Qur'an 5:32).

This verse, in accordance with the Mosaic Law, maintains that the punishment for murder is the death penalty. "Mischief in the land" has been interpreted universally to refer to one who upsets the stability of the entire nation or community, in that his actions seriously damage the society, either through corruption, war or otherwise.

Judaism

The official teachings of Judaism approve the death penalty in principle but the standard of proof required for application of death penalty is extremely stringent. In practice, it has been abolished by various Talmudic decisions, making the situations in which a death sentence could be passed effectively impossible and hypothetical. A capital case could not be tried by a normal Beit Din of three judges, it can only be adjudicated by a Sanhedrin of a minimum of 23 judges.[171] Forty years before the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem in approximately the year 70 CE,[172] i.e. in approximately 30 CE, the Sanhedrin effectively abolished capital punishment,[173] making it a hypothetical upper limit on the severity of punishment, fitting in finality for God alone to use, not fallible people.

The 12th-century Jewish legal scholar, Maimonides said:

- "It is better and more satisfactory to acquit a thousand guilty persons than to put a single innocent one to death."[174]

Maimonides argued that executing a defendant on anything less than absolute certainty would lead to a slippery slope of decreasing burdens of proof, until we would be convicting merely "according to the judge's caprice". Maimonides was concerned about the need for the law to guard itself in public perceptions, to preserve its majesty and retain the people's respect.[175]

The state of Israel retains the death penalty only for Nazis convicted of crimes against humanity.[176] The only execution in Israeli history occurred in 1961, when Adolf Eichmann, one of the principal organizers of the Holocaust, was put to death after his trial in Jerusalem.

See also

- Mandatory death sentence

- Death by a Thousand Cuts (book)

- Eye for an eye

- List of people who were beheaded

- The Death Penalty: Opposing Viewpoints (2002) (book)

- UN moratorium on the death penalty

- World Coalition Against the Death Penalty

- Death in custody

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/abolitionist-and-retentionist-countries

- ↑ Kronenwetter 2001, p. 202

- ↑ http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/pages/frontline/shows/execution/readings/history.html

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 "Abolitionist and retentionist countries". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ http://www.tnp.no/norway/panorama/4100-university-of-oslo-norway-calls-world-universities-against-death-penalty

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/10/09/iran-saudi-arabia-sudan-end-juvenile-death-penalty

- ↑ http://www.hrw.org/news/2010/10/09/iran-saudi-arabia-sudan-end-juvenile-death-penalty

- ↑ "Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "moratorium on the death penalty". United Nations. 15 November 2007. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Asia Times Online – The best news coverage from South Asia". Asia Times. 13 August 2004. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Coalition mondiale contre la peine de mort – Indonesian activists face upward death penalty trend – Asia – Pacific – Actualités". Worldcoalition.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "No serious chance of repeal in those states that are actually using the death penalty". Egovmonitor.com. 25 March 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ AG Brown says he'll follow law on death penalty

- ↑ "Lawmakers Cite Economic Crisis in Effort to Ban Death Penalty". Fox News Channel. 7 April 2010. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "death penalty is not likely to end soon in US". International Herald Tribune. 29 March 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Death penalty repeal unlikely says anti-death penalty activist". Axisoflogic.com. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "A new Texas? Ohio's death penalty examined – Campus". Media.www.thelantern.com. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "THE DEATH PENALTY IN JAPAN-FIDH > Human Rights for All / Les Droits de l'Homme pour Tous". Fidh.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Shot at Dawn, campaign for pardons for British and Commonwealth soldiers executed in World War I". Shot at Dawn Pardons Campaign. Retrieved 2006-07-20.

- ↑ So common was the practice of compensation that the word murder is derived from the French word mordre (bite) a reference to the heavy compensation one must pay for causing an unjust death. The "bite" one had to pay was used as a term for the crime itself: "Mordre wol out; that se we day by day." – Geoffrey Chaucer (1340–1400), The Canterbury Tales, The Nun's Priest's Tale, l. 4242 (1387–1400), repr. In The Works of Geoffrey Chaucer, ed. Alfred W. Pollard, et al. (1898).

- ↑ Translated from Waldmann, op.cit., p. 147.

- ↑ Lindow, op.cit. (primarily discusses Icelandic things).

- ↑ Schabas, William (2002). The Abolition of the Death Penalty in International Law. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-81491-X.

- ↑ Robert. "Greece, A History of Ancient Greece, Draco and Solon Laws". History-world.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "capital punishment (law) - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Capital punishment in the Roman Empire". En.allexperts.com. 30 January 2001. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Benn, p. 8.

- ↑ Benn, pp. 209–210

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Benn, p. 210

- ↑ "History of the Death Penalty". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ Moses Maimonides, The Commandments, Neg. Comm. 290, at 269–71 (Charles B. Chavel trans., 1967).

- ↑ "Islam and capital punishment". BBC. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ The Caliphate: Its Rise, Decline, and Fall., William Muir

- ↑ Hooker, Richard (July 14, 1999). "arkan ad-din the five pillars of religion". Washington State University.

- ↑ http://global-right-path.webs.com/Siraat-al-Mustaqeem/102-Islaamic_Sharia_Law.pdf

- ↑ Zipes, Jack David (1999). When Dreams Came True: Classical Fairy Tales and Their Tradition. Routledge. pp. 57–8. ISBN 0-415-92151-1.

- ↑ Bedau, Hugo Adam (Autumn 1983). "Bentham's Utilitarian Critique of the Death Penalty". The Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology (Northwestern University School of Law) 74 (3): 1033–1065. doi:10.2307/1143143. JSTOR 1143143.

- ↑ Durant, Will and Ariel, The Story of Civilization, Volume IX: The Age of Voltaire New York, 1965, page 71

- ↑ Durant, Will and Ariel, The Story of Civilization, Volume IX: The Age of Voltaire New York, 1965, page 72,

- ↑ Dando Shigemitsu (1999). The criminal law of Japan: the general part. p. 289.

- ↑ "Patriots ignore greatest brutality". The Sydney Morning Herald. 13 August 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ Conquest, Robert, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, New York, pages 485–86

- ↑ French, Howard (7 June 1995). "South Africa's Supreme Court Abolishes Death Penalty". The New York Times. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ↑ South Africa: Constitutional Court (6 June 1995). S v Makwanyane and Another (CCT3/94) (1995) ZACC 3; 1995 (6) BCLR 665; 1995 (3) SA 391; (1996) 2 CHRLD 164; 1995 (2) SACR 1. Southern African Legal Information Institute. Retrieved 2012-12-04.

- ↑ "• Travel & Exploration • A Ride to India across Persia and Baluchistan • CHAPTER VII. ISPAHAN – SHIRAZ". Explorion.net. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ Article from the Connecticut Courant (1 December 1803)

- ↑ The Execution of Caleb Adams, 2003

- ↑ "Encyclopedia of Shinto". kokugakuin.ac.jp. Retrieved 2011-09-05.

- ↑ "Venezuela: A Country Study (The Century of Caudillismo)". countrystudies.us. Retrieved 2012-08-04.

- ↑ "Death Penalty". Newsbatch.com. 1 March 2005. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "History of Capital Punishment". Stephen-stratford.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ See Caitlin pp. 420–422

- ↑ Simpson, Ian (2 May 2013). "Maryland becomes latest U.S. state to abolish death penalty". Yahoo! News. Reuters. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013.

- ↑ "Troy Davis' execution and the limits of Twitter". BBC News. 23 September 2011.

- ↑ "In U.S., 64% Support Death Penalty in Cases of Murder". Gallup.com. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-us-canada-23075873

- ↑ http://oklahomawatch.org/2013/02/21/this-news-brief-has-a-featured-image/

- ↑ "Death Penalty: Hands Off Cain Announces Abolition In Gabon". Handsoffcain.info. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Abolish the death penalty". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Abolitionist and Retentionist Countries". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2008-06-10.

- ↑ http://www.eai.nus.edu.sg/BB412.pdf

- ↑ "THE DEATH PENALTY IN 2011". Amnesty.org. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Death sentences and executions 2011" (PDF). Amnesty. Retrieved 2013-06-29.

- ↑ Hogg, Chris (29 December 2009). "China executions shrouded in secrecy". BBC News. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "The most important facts of 2008 (and the first six months of 2009)". Handsoffcain.info. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Document - Singapore should join global trend and establish a moratorium on executions". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ Martin Luther King, Jr (16 March 2010). "Heroin smuggler challenges Singapore death sentence". Yoursdp.org. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ "Indonesia: First Execution in 4 Years a Major Setback". Human Rights Watch. http://www.hrw.org. Retrieved 17 May 2013.

- ↑ "International Polls & Studies". The Death Penalty Information Center. Retrieved 2008-04-01.

- ↑ http://hub.coe.int/what-we-do/human-rights/death-penalty

- ↑ http://www.handsoffcain.info/bancadati/schedastato.php?idcontinente=20&nome=ukraine

- ↑ "China Against Death Penalty ( CADP)". Cadpnet.com. 2012-03-31. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "AIUK : Sri Lanka: President urged to prevent return to death penalty after 29-year moratorium". Amnesty.org.uk. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Brian Evans, "The Death Penalty In 2011: Three Things You Should Know", Amnesty International, 26 March 2012, in particular the map, "Executions and Death Sentences in 2011"

- ↑ "Mongolia takes ‘vital step forward’ in abolishing the death penalty", Amnesty International, 5 January 2011

- ↑ "Akmal Shaikh told of execution for drug smuggling". BBC News. 28 December 2009. Retrieved 2009-12-29.

- ↑ "毒品危害防制條例". 20 May 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ US Code (18 U.S.C. 3591),

- ↑ "Juvenile executions (except US)". Internationaljusticeproject.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 80.2 "Iran changes law for execution of juveniles". Iranwpd.com. 10 February 2012. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ 81.0 81.1 "مجازات قصاص برای افراد زیر 18 سال ممنوع شد". Ghanoononline.ir. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Executions of juveniles since 1990". Amnesty International. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Stop Child Executions! Ending the death penalty for child offenders". Amnesty International. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-12-22. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Execution of Juveniles in the U.S. and other Countries". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Rob Gallagher, Table of juvenile executions in British America/United States, 1642–1959

- ↑ Supreme Court bars executing mentally retarded CNN.com Law Center. 25 June 2002

- ↑ "HRW Report". Human Rights Watch. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ UNICEF, Convention of the Rights of the Child – FAQ: "The Convention on the Rights of the Child is the most widely and rapidly ratified human rights treaty in history. Only two countries, Somalia and the United States, have not ratified this celebrated agreement. Somalia is currently unable to proceed to ratification as it has no recognised government. By signing the Convention, the United States has signaled its intention to ratify, but has yet to do so."

- ↑ Iranian activists fight child executions, Ali Akbar Dareini, Associated Press, 17 September 2008. Retrieved 2008-09-22.

- ↑ O'Toole, Pam (2007-06-27). "Iran rapped over child executions". BBC News. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "Iran Does Far Worse Than Ignore Gays, Critics Say". Foxnews.com. September 25, 2007. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ Iranian hanged after verdict stay; BBCnews.co.uk; 2007-12-06; Retrieved 2007-12-06

- ↑ http://www.amnesty.org/en/news-and-updates/news/juveniles-among-five-men-beheaded-saudi-arabia-20090512

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-middle-east-21767667

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-asia-20959228

- ↑ "Somali woman executed by stoning". BBC News. 27 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Stoning victim 'begged for mercy'". BBC News. 4 November 2008. Retrieved 2010-04-14.

- ↑ "Somalia: Girl stoned was a child of 13". Amnesty International. 31 October 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-31.

- ↑ "Somalia to Ratify UN Child Rights Treaty", allAfrica.com, 20 November 2013.

- ↑ "UNICEF lauds move by Somalia to ratify child convention". Xinhua News Agency. 20 November 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Methodes of execution by country". Nutzworld.com. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Methods of execution – Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "Death penalty Bulletin No. 4-2010" (in (Norwegian)). Translate.google.no. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "INFORMATION ON DEATH PENALTY" (in (Norwegian)). Amnesty International. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ "execution methods by country". Executions.justsickshit.com. Retrieved 2011-02-23.

- ↑ Brian Evans, "The Death Penalty In 2011: Three Things You Should Know", Amnesty International, March 26, 2012, in particular the map, "Executions and Death Sentences in 2011"

- ↑ "ACLU Capital Punishment Project (CPP)". Aclu.org. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ James Pitkin. ""Killing Time" | January 23rd, 2008". Wweek.com. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Film Robert Blecker want me dead, about retributive justice and capital punishment

- ↑ "The High Cost of the Death Penalty". Death Penalty Focus. Retrieved 2008-06-27.

- ↑ "Death Penalty News & Updates". People.smu.edu. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ Joel Feinberg: Voluntary Euthanasia and the Inalienable Right to Life The Tanner Lecture on Human Values, 1 April 1977.

- ↑ "Innocence and the Death Penalty". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Capital Defense Weekly Archived 4 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine

- ↑ "Executed Innocents". Justicedenied.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "Wrongful executions". Mitglied.lycos.de. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ "The Innocence Project – News and Information: Press Releases". Innoccenceproject.org. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

- ↑ Lundin, Leigh (10 July 2011). "Casey Anthony Trial– Aftermath". Capital Punishment. Orlando: Criminal Brief. "With 400 condemned on death row, Florida is an extremely aggressive death penalty state, a state that will even execute for drug trafficking."

- ↑ "Executed But Possibly Innocent | Death Penalty Information Center". Deathpenaltyinfo.org. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ Amnesty International, "Singapore – The death penalty: A hidden toll of executions" (January 2004)

- ↑ "New York Law School :: Robert Blecker". Nyls.edu. Retrieved 2013-04-14.

- ↑ http://www.bbc.co.uk/ethics/capitalpunishment/against_1.shtml#section_4

- ↑ http://www.amnestyusa.org/our-work/issues/death-penalty/us-death-penalty-facts/death-penalty-and-race

- ↑ http://www.eji.org/deathpenalty/racialbias

- ↑ http://www.ncadp.org/pages/racial-bias

- ↑ Thomas Hubert (29 June 2007). "Journée contre la peine de mort : le monde décide!" (in French). Coalition Mondiale.

- ↑ "Abolish the death penalty | Amnesty International". Web.amnesty.org. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "UN set for key death penalty vote". Amnesty International. 9 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ↑ "Directorate of Communication – The global campaign against the death penalty is gaining momentum – Statement by Terry Davis, Secretary General of the Council of Europe". Wcd.coe.int. 2007-11-16. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "UN General Assembly - News Stories". Un.org. Retrieved 2012-12-12.

- ↑ "U.N. Assembly calls for moratorium on death penalty". Reuters. 18 December 2007.

- ↑ "Second Optional Protocol to the ICCPR". Office of the UN High Commissioner on Human Rights. Retrieved 2007-12-08.

- ↑ http://www.amnesty.org/en/death-penalty/death-sentences-and-executions-in-2012

- ↑ "Prezydent podpisał ustawy dot. zniesienia kary śmierci" [The President signed the Bill. the abolition of the death penalty] (in Polish). gazeta.pl. Retrieved 2013-09-07.

- ↑ https://treaties.un.org/Pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-12&chapter=4&lang=en

- ↑ http://www.oas.org/juridico/english/sigs/a-53.html

- ↑ New Zealand, South Africa, and most European nations except Belarus, Includes Albania, Andorra, Armenia, Austria, Azerbaijan, Belgium, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Croatia, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Estonia, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Israel, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Liechtenstein, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Malta, Moldova, Monaco, the Netherlands, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, San Marino, Serbia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Ukraine, United Kingdom and Vatican City (Belarus is excluded)

- ↑ http://www.amnesty.org/en/news-and-updates/news/burundi-abolishes-death-penalty-bans-homosexuality-20090427

- ↑ http://www.handsoffcain.info/archivio_news/index.php?iddocumento=15302086&mover=0

- ↑ http://www.handsoffcain.info/bancadati/schedastato.php?idstato=17000190

- ↑ http://www.sudantribune.com/spip.php?article46452

- ↑ "Dhammika Sutta: Dhammika". Accesstoinsight.org. 11 July 2010. Retrieved 2012-04-30.

- ↑ "Japan hangs two more on death row (see also paragraph 11)". BBC News. 28 October 2008. Retrieved 2010-08-23.