Ed McBain

| Ed McBain | |

|---|---|

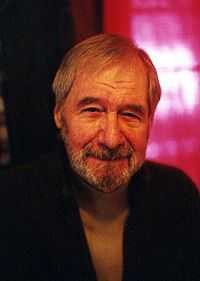

Ed McBain in March 2001 | |

| Born |

Salvatore Albert Lombino October 15, 1926 New York City, U.S. |

| Died |

July 6, 2005 (aged 78) Weston, Connecticut |

| Pen name | Evan Hunter, Hunt Collins, Curt Cannon, Dean Hudson, Richard Marsten, Ezra Hannon, John Abbott |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, screenwriter |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1951–2005 |

| Genres | Crime fiction, mystery fiction, science fiction |

| Spouse(s) | Anita Melnick, 1949 (divorced); Mary Vann Finley, 1973 (divorced); Dragica Dimitrijevic, 1997 (until his death) |

| Children | 3 (Richard, Mark, Ted); 1 stepdaughter (Amanda) |

Ed McBain (October 15, 1926 – July 6, 2005) was an American author and screenwriter. Born Salvatore Albert Lombino, he legally adopted the name Evan Hunter in 1952. While successful and well known as Evan Hunter, he was even better known as Ed McBain, a name he used for most of his crime fiction, beginning in 1956.

Life

Early life

Salvatore Lombino was born and raised in New York City, living in East Harlem until the age of 12, at which point his family moved to the Bronx. He attended Olinville Junior High School, then Evander Childs High School, before winning an Art Students League scholarship. Later, he was admitted as an art student at Cooper Union. Lombino served in the Navy in World War II, writing several short stories while serving aboard a destroyer in the Pacific. However, none of these stories were published until after he had established himself as an author in the 1950s.

After the war, Lombino returned to New York and attended Hunter College, graduating Phi Beta Kappa, majoring in English and psychology, with minors in dramatics and education. He published a weekly column in the Hunter College newspaper as "S.A. Lombino". In 1981, Lombino was inducted into the Hunter College Hall of Fame where he was honored for outstanding professional achievement.[1]

While looking to start a career as a writer, Lombino took a variety of jobs, including 17 days as a teacher at Bronx Vocational High School in September 1950. This experience would later form the basis for his 1954 novel The Blackboard Jungle.

In 1951, Lombino took a job as an executive editor for the Scott Meredith Literary Agency, working with authors such as Arthur C. Clarke, P.G. Wodehouse, Lester del Rey, Poul Anderson, and Richard S. Prather. He made his first professional short-story sale that same year, a science-fiction tale titled "Welcome Martians", credited to S.A. Lombino.

Name change and pen names

Soon after his initial sale, Lombino sold stories under the pen names Evan Hunter and Hunt Collins. The name Evan Hunter is generally believed to have been derived from two schools he attended, Evander Childs High School and Hunter College, although the author himself would never confirm that. (He did confirm that the name Hunt Collins was derived from Hunter College.) Lombino legally changed his name to Evan Hunter in May 1952, after an editor told him that a novel he wrote would sell more copies if credited to Evan Hunter than it would if it were credited to S.A. Lombino. Thereafter, he used the name Evan Hunter both personally and professionally.

As Evan Hunter, he gained notice with his 1954 novel The Blackboard Jungle. Dealing with juvenile crime and the New York City public school system, the film version followed in 1955. During this era, Hunter also wrote a great deal of genre fiction. He was advised by his agents that publishing too much fiction under the Hunter byline, or publishing any crime fiction as Evan Hunter, might weaken his literary reputation. As a consequence, during the 1950s Hunter used the pseudonyms Curt Cannon, Hunt Collins, and Richard Marsten for much of his crime fiction. A prolific author in several genres, Hunter also published approximately two dozen science fiction stories and four SF novels between 1951 and 1956 under the names S.A. Lombino, Evan Hunter, Richard Marsten, D.A. Addams and Ted Taine.

Ed McBain, his best known pseudonym, was first used in 1956, with Cop Hater, the first novel in the 87th Precinct crime series. Hunter revealed that he was McBain in 1958, but continued to use the pseudonym for decades, notably for the 87th Precinct series, and the Matthew Hope detective series. He retired the pen names of Cannon, Marsten, Collins, Addams and Taine around 1960. From then on crime novels were generally attributed to McBain, and other sorts of fiction to Hunter. Reprints of crime-oriented stories and novels written in the 1950s previously attributed to other pseudonyms were re-issued under the McBain byline. Hunter stated that the division of names allowed readers to know what to expect: McBain novels had a consistent writing style, while Hunter novels were more varied.

Under the Hunter name, novels steadily appeared throughout the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, including Come Winter (1973), and Lizzie (1984). Hunter was also successful as screenwriter for film and television. He wrote the screenplay of the Hitchcock film The Birds (1963) loosely adapted from a Daphne du Maurier short story. In the process of adapting Winston Graham's novel Marnie for Hitchcock, Hunter and the director disagreed on the rape scene, and the writer was sacked. Hunter's other screenplays included Strangers When We Meet (1960), based on his own 1958 novel; and Fuzz (1972), based on the 1968 "87th Precinct" novel of the same name, which he had written as Ed McBain.

From 1958 until his death, McBain's "87th Precinct" novels appeared at a rate of approximately one or two novels a year. NBC ran a police drama also called 87th Precinct during the 1961–62 season based on McBain's work.

From 1978 to 1998, McBain also published a series about lawyer Matthew Hope; books in this series appeared every year or two, and usually had titles derived from well-known children's stories. For about a decade, from 1984 to 1994, Hunter published no fiction under his own name. In 2000, a novel called Candyland appeared that was credited to both Hunter and McBain. The two-part novel opened in Hunter's psychologically-based narrative voice before switching to McBain's customary police procedural style. Aside from McBain, Hunter used at least two other pseudonyms for his fiction after 1960; Doors (1975) was originally attributed to Ezra Hannon, before being reissued as a work by McBain, and Scimitar (1992) was credited to John Abbott.

As well, Hunter has long been rumoured to have written an unknown number of pornographic novels for William Hamling's publishing houses as "Dean Hudson". Though Hunter consistently denied writing any books as Hudson right up to his death, apparently his agent Scott Meredith sold books to Hamling's company as Hunter's work, receiving payments for these books in cash. However, Hunter—if he did write the novels—never dealt with the publisher directly, and no records were kept by Meredith or Hamling of these cash transactions (presumably to avoid paying taxes). As well, Meredith may have forwarded novels to Hamling by any number of authors, claiming these novels were by Hunter simply in order to make a sale. Because of all these factors, it is impossible to do more than speculate as to which specific Hudson books may be Hunter's work.[2] Ninety-three novels were published under the Hudson name between 1961 and 1969, and even the most avid proponents of the Hunter-as-Hudson theory do not believe Hunter is responsible for all 93.

In addition to his many books, Hunter also gave advice to other authors in his article, "Dig in and get it done: no-nonsense advice from a prolific author (aka Ed McBain) on starting and finishing your novel". In it he advises authors to "find their voice for it is the most important thing in any novel."

Private life

He had three sons: Richard Hunter, an author, speaker and advisor to CIOs on business value and risk issues, as well as a harmonica player; Mark Hunter, an academic, educator, investigative reporter and author; and Ted Hunter, a painter, who died in 2006.[3]

Evan Hunter (aka Ed McBain) died from laryngeal cancer in 2005, aged 78, in Weston, Connecticut.[4]

See also

References

- ↑ http://library.hunter.cuny.edu/pdf/archives/AlumniFindingAid.pdf

- ↑ "The Whitewash Jungle" by Earl Kemp, Earl Kemp fanzine, February 2006.

- ↑ http://www.omnilexica.com/?q=ted+hunter

- ↑ http://www.nytimes.com/2005/07/07/books/07hunter.html?pagewanted=all&_r=0

External links

- Official website

- Evan Hunter at the Internet Movie Database

- Evan Hunter at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Works by or about Ed McBain in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Works by or about Ed McBain in libraries (WorldCat catalog)

- Ed McBain and Evan Hunter on Internet Book List

- http://www.wnyc.org/stream/ram.py?file=/lopate/mcbain.mp3 2001 audio interview with Leonard Lopate of WNYC/NPR — RealAudio

- Ed McBain / Evan Hunter bibliographies 1–2 at HARD-BOILED site (Comprehensive Bibliographies by Vladimir)