History of Europe

The history of Europe covers the people inhabiting the European continent since it was first populated in prehistoric times to the present. The first Homo sapiens arrived between 45,000 and 25,000 BC.

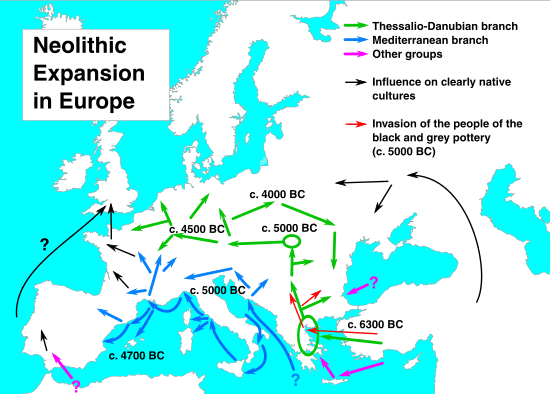

The earliest settlers to Prehistoric Europe came during the paleolithic era. The adoption of agriculture around 7000 BC ushered in the neolithic age. Neolithic Europe lasted for 4000 years, overlapping with metal-using cultures that gradually spread throughout the continent. Technological advances during the prehistoric age came via the Mediterranean peoples, spreading gradually to the northwest. Some of the best-known civilizations of prehistoric Europe were the Minoan and the Mycenaean, which flourished during the Bronze Age until they collapsed in a short period of time around 1200 BC.

The period known as classical antiquity began with the rise of the city-states of Ancient Greece. Greek influence reached its zenith under the expansive empire of Alexander the Great, spreading throughout Asia. Northern and western Europe were dominated by the La Tène culture, a precursor to the Celts. Rome, a small city-state traditionally founded in 753 BC, would grow to become the Roman Republic in 509 BC and would succeed Greek culture as the dominant Mediterranean civilization. The events during the rule of Julius Caesar led to reorganization of the Republic into the Roman Empire. This empire was later divided by the emperor Diocletian into the Western and Eastern empires. During the 4th and 5th centuries, the Germanic peoples of northern Europe grew in strength and repeated attacks led to the Fall of the Western Roman Empire in AD 476, a date which traditionally marks the end of the classical period and the start of the Middle Ages.

During the Middle Ages, the Eastern Roman Empire survived, though modern historians refer to this state as the Byzantine Empire. In Western Europe, Germanic peoples moved into positions of power in the remnants of the former Western Roman Empire and established kingdoms and empires of their own. Of all of the Germanic peoples, the Franks would rise to a position of hegemony over western Europe, the Frankish Empire reaching its peak under Charlemagne around AD 800. This empire was later divided into several parts; West Francia would evolve into the Kingdom of France, while East Francia would evolve into the Holy Roman Empire, a precursor to modern Germany. The British Isles were the site of several large-scale migrations. Native Celtic peoples had been marginalized during the period of Roman Britain, and when the Romans abandoned the British Isles during the 400s, waves of Germanic Anglo-Saxons migrated to southern Britain and established a series of petty kingdoms in what would eventually develop into the Kingdom of England by AD 927. During this period, the kingdoms of Poland and Hungary were organized as well.

The Viking Age, a period of migrations of Scandinavian peoples, occurred from the late 700s to the middle 1000s. Chief among the Viking states was the Empire of Cnut the Great, a Danish leader who would become king of England, Denmark, and Norway. The Normans, a Viking people who settled in Northern France and founded the Duchy of Normandy, would have a significant impact on many parts of Europe, from the Norman conquest of England to Southern Italy and Sicily. Another Scandinavian people, the Rus' people, would go on to found Kievan Rus', an early state which was a precursor for the modern country of Russia. As the Viking Age drew to a close, the period known as the Crusades, a series of religiously motivated military expeditions originally intended to bring the Levant back into Christian rule, began. Several Crusader states were founded in the eastern Mediterranean. These were all short-lived. The Crusaders would have a profound impact on many parts of Europe. Their Sack of Constantinople in 1204 brought an abrupt end to the Byzantine Empire. Though it would later be re-established, it would never recover its former glory. The Crusaders would establish trade routes that would develop into the Silk Road and open the way for the merchant republics of Genoa and Venice to become major economic powers. Crusader missions to the Baltic lands would establish the State of the Teutonic Order. The Reconquista, a related movement, worked to reconquer Iberia for Christendom.

Eastern Europe in the High Middle Ages was dominated by the rise, and later fall, of the Mongol Empire. Led by Genghis Khan, the Mongols were a group of steppe nomads that established a decentralized empire that, at its height, extended from China in the east to the Black and Baltic seas in Europe. The Kievan Rus' state had broken up, replaced by several small warring states. In the face of the Mongol conquests, many of these states paid tribute to the Mongols, becoming effective vassals. As Mongol power waned towards the Late Middle Ages, the Grand Duchy of Moscow rose to become the strongest of the numerous Russian principalities and republics and would itself grow into the Tsardom of Russia in 1547. The Late Middle Ages represented a period of upheaval in Europe. The epidemic known as the Black Death and an associated famine caused demographic catastrophe in Europe as the population plummeted. Dynastic struggles and wars of conquest kept many of the states of Europe at war for much of the period. In Scandinavia, the Kalmar Union dominated the political landscape, while England fought with Scotland in the Wars of Scottish Independence and with France in the Hundred Years' War. In Central Europe, the Polish–Lithuanian union became a large territorial empire, while the Holy Roman Empire, which was an elective monarchy, came to be dominated by the House of Habsburg, who would turn it into a hereditary position in all but name. Russia continued to expand southward and eastward into former Mongol lands as well. In the Balkans, the Ottoman Empire, a Turkish state originating in Anatolia, encroached steadily on former Byzantine lands, culminating in the Fall of Constantinople in 1453.

Beginning roughly in the 14th century in Florence, and later spreading through Europe with the development of the printing press, a Renaissance of knowledge challenged traditional doctrines in science and theology, with the rediscovery of classical Greek and Roman knowledge. Simultaneously, the Protestant Reformation under German Martin Luther questioned Papal authority. Henry VIII sundered the English Church, allying in ensuing religious wars between German and Spanish rulers. The Reconquista of Portugal and Spain led to a series of oceanic explorations resulting in the Age of Discovery that established direct links with Africa, the Americas, and Asia, while religious wars continued to be fought in Europe,[4] which ended in 1648 with the Peace of Westphalia. The Spanish crown maintained its hegemony in Europe and was the leading power on the continent until the signing of the Treaty of the Pyrenees, which ended a conflict between Spain and France that had begun during the Thirty Years' War. An unprecedented series of major wars and political revolutions took place around Europe and indeed the world in the period between 1610 and 1700. Observers at the time, and many historians since, have argued that wars caused the revolutions.[5]

European overseas expansion led to the rise of colonial empires, producing the Columbian Exchange.[6] The combination of resource inflows from the New World and the Industrial Revolution of Great Britain, allowed a new economy based on manufacturing instead of subsistence agriculture.[7] Starting in 1775, British Empire colonies in America revolted to establish a representative government. Political change in continental Europe was spurred by the French Revolution under the motto liberté, égalité, fraternité. The ensuing French leader, Napoleon Bonaparte, conquered and enforced reforms through war up to 1815.

The period between 1815 and 1871 saw a large number of revolutionary attempts and independence wars. In France and the United Kingdom, socialism and trade union activity developed. The last vestiges of serfdom were abolished in Russia in 1861,[8] and Balkan nations began to regain independence from the Ottoman Empire. After the Franco-Prussian War, Germany and Italy unified into nation states, and most European states had become constitutional monarchies by 1871. Rivalry in a scramble for empires spread. The outbreak of the First World War was precipitated by a series of struggles among the Great Powers. War and poverty triggered the Russian Revolution which led to the formation of the communist Soviet Union. Hard conditions imposed on Germany by the Treaty of Versailles and the Great Depression led to the rise of fascism in Germany as well as in Italy, Spain, and other countries. The rise of irredentist regimes such as Nazi Germany led to a Second World War.

Following the end of the Second World War, Europe was divided by the Iron Curtain. The Central-East was dominated by communist countries under the Soviet Union's economic and military leadership, while the rest was dominated by capitalist countries under the economic and military leadership of the United States. Both of the leading countries were superpowers. Most non-communist European countries joined a US-led military alliance (NATO) and formed the European Economic Community amongst themselves. The countries in the Soviet sphere of influence joined the military alliance known as the Warsaw Pact and the economic bloc called Comecon. Socialist parties governed some countries in the West and North of Europe from time to time, and in one case (Portugal), socialist concepts were even adopted into the country's constitution. A few small countries were neutral. The Soviet economic and political system collapsed in 1989-91, leading first to the end of communism in the satellite countries in 1989, and then to the dissolution of the Soviet Union itself in 1991. As a consequence, Germany was reunited, Europe's economic integration deepened, the continent became depolarised, and the European Union expanded to include many of the formerly communist European countries. The European Community came under increasing pressure because of the worldwide recession after 2008, with issues of financial aid to near-bankrupt countries, increasing intolerance of poorly assimilated immigrants, distrust of Germany's increasing power, tensions with Russia, rejection of Turkey's membership, and growing skepticism about the EU's future.

Prehistory

Homo erectus migrated from Africa to Europe before the emergence of modern humans.[citation needed] The bones of the earliest Europeans are found in Dmanisi, Georgia, dated at 1.8 million years ago. Lézignan-la-Cèbe in France and Kozarnika in Bulgaria are also amongst the oldest Palaeolithic sites in Europe.

The earliest appearance of anatomically modern people in Europe has been dated to 35,000 BC, usually referred to as the Cro-Magnon man. Some locally developed transitional cultures (Szeletian in Central Europe and Châtelperronian in the Southwest) use clearly Upper Palaeolithic technologies at very early dates.

Nevertheless, the definitive advance of these technologies is made by the Aurignacian culture. The origins of this culture can be located in what is now Bulgaria (proto-Aurignacian or Bachokirian) and Hungary (first full Aurignacian). By 35,000 BC, the Aurignacian culture and its technology had extended through most of Europe. The last Neanderthals seem to have been forced to retreat during this process to the southern half of the Iberian Peninsula.

Around 24,000 BC two new technologies/cultures appeared in the south-western region of Europe: Solutrean and Gravettian. The Gravettian technology/culture has been theorised to have come with migrations of people from the Middle East, Anatolia, and the Balkans.

Around 16,000 BC, Europe witnessed the appearance of a new culture, known as Magdalenian, possibly rooted in the old Aurignacian one. This culture soon superseded the Solutrean area and the Gravettian of mainly France, Spain, Germany, Italy, Poland, Portugal and Ukraine. The Hamburg culture prevailed in Northern Europe in the 14th and the 13th millennium BC. Around 12,500 BC, the Würm glaciation ended. Slowly, through the following millennia, temperatures and sea levels rose, changing the environment of prehistoric people. Nevertheless, Magdalenian culture persisted until c. 10,000 BC, when it quickly evolved into two microlithist cultures: Azilian (Federmesser), in Spain and southern France, and then Sauveterrian, in northern France and Central Europe, while in Northern Europe the Lyngby complex succeeded the Hamburg culture with the influence of the Federmesser group as well. Evidence of permanent settlement dates from the 8th millennium BC in the Balkans. The Neolithic reached Central Europe in the 6th millennium BC and parts of Northern Europe in the 5th and 4th millennium BC.

Lepenski Vir – Vinča – Cucuteni cultures 7000–2750 BC

Lepenski Vir (Лепенски Вир, Lepen Whirl) is an important Mesolithic archaeological site located in Serbia in the central Balkan peninsula. It consists of one large settlement with around ten satellite villages. The evidence suggests the first human presence in the locality around 7000 BC with the culture reaching its peak between 5300 BC and 4800 BC. In 7000 BC the settlement had a population under 100, In later periods the problems of overpopulation of the original settlement became evident, This is clearly evident in the layout of the Lepenski Vir settlement. The village is well planned. All houses are built according to one complex geometric pattern. 136 buildings, settlements and altars were found in the initial excavations in 1965–1970. The Lepenski Vir culture were a forerunner to the Vinča-Turdaș culture, dated to the period 5500–4500 BC in the same area of the Balkans, during the Vinča era the area sustained population growth led to an unprecedented level of settlement size and density along with the population of areas that were bypassed by earlier settlers. Vinča settlements were considerably larger than any other contemporary European culture, in some instances surpassing the cities of the Aegean and early Near Eastern Bronze Age a millennium later. The largest sites, more than 29 hectares, may have had populations of up to 2,500 individuals.[9] According to Marija Gimbutas, the Vinča culture was part of Old Europe – a relatively homogeneous, peaceful and matrifocal culture that occupied Europe during the Neolithic. According to this theory its period of decline was followed by an invasion of warlike, horse-riding Proto-Indo-European tribes from the Pontic-Caspian steppe.[10] The Vinča site of Pločnik has produced the earliest example of copper tools in the world. Copper ores were mined on a large scale at sites like Rudna Glava, but only a fraction were smelted and cast into metal artefacts – and these were ornaments and trinkets rather than functional tools, which continued to be made from chipped stone, bone and antler. It is likely that the primary use of mined ores was in their powdered form, in the production of pottery or as bodily decoration.[11]

This period is associated with the Vinča symbols, which are conjectured to be an early form of proto-writing alongside with the Dispilio Tablet (5260 BC) from northern Greece not far from The Vinca Culture, the Tărtăria tablets dating back to around 5300 BC. This means that the Vinča finds predate the proto-Sumerian pictographic script from Uruk (modern Iraq), which is usually considered as the oldest known script, by more than a thousand years. The Cucuteni-Trypillian culture 5508–2750 BC was the first big civilisation in Europe and among the earliest in the world. It was a late Neolithic archaeological civilization from the Carpathian Mountains to the Dniester and Dnieper regions in modern-day Romania, Moldova, and Ukraine, encompassing an area of more than 350,000 km2 (140,000 sq mi).[12] At its peak the Cucuteni-Trypillian culture built the largest settlements in Neolithic Europe, some of which had populations of up to 15,000 inhabitants.[13] Likewise, their density was very high, with the settlements averagely spaced 3 to 4 kilometres apart.[14]

Minoans and Mycenae 2700–1100 BCE

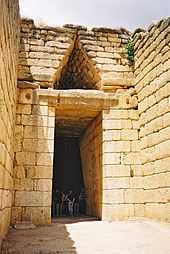

The first well-known literate civilization in Europe was that of the Minoans. The Minoan civilization was a Bronze Age civilization that arose on the island of Crete and flourished from approximately the 27th century BCE to the 15th century BCE.[15] It was rediscovered at the beginning of the 20th century through the work of the British archaeologist Arthur Evans. Will Durant referred to it as "the first link in the European chain".[16]

The Minoans were replaced by the Mycenaean civilization which flourished during the period roughly between 1600 BCE, when Helladic culture in mainland Greece was transformed under influences from Minoan Crete, and 1100 BCE. The major Mycenaean cities were Mycenae and Tiryns in Argolis, Pylos in Messenia, Athens in Attica, Thebes and Orchomenus in Boeotia, and Iolkos in Thessaly. In Crete, the Mycenaeans occupied Knossos. Mycenaean settlement sites also appeared in Epirus,[17][18] Macedonia,[19][20] on islands in the Aegean Sea, on the coast of Asia Minor, the Levant,[21] Cyprus[22] and Italy.[23][24] Mycenaean artefacts have been found well outside the limits of the Mycenean world.

Quite unlike the Minoans, whose society benefited from trade, the Mycenaeans advanced through conquest. Mycenaean civilization was dominated by a warrior aristocracy. Around 1400 BCE, the Mycenaeans extended their control to Crete, centre of the Minoan civilization, and adopted a form of the Minoan script (called Linear A) to write their early form of Greek in Linear B.

The Mycenaean civilization perished with the collapse of Bronze-Age civilization in the eastern shored of the Mediterranean Sea. The collapse is commonly attributed to the Dorian invasion, although other theories describing natural disasters and climate change have been advanced as well. Whatever the causes, the Mycenaean civilization had definitely disappeared after LH III C, when the sites of Mycenae and Tirynth were again destroyed and lost their importance. This end, during the last years of the 12th century BCE, occurs after a slow decline of the Mycenaean civilization, which lasted many years before dying out. The beginning of the 11th century BCE opened a new context, that of the protogeometric, the beginning of the geometric period, the Greek Dark Ages of traditional historiography.

Classical antiquity

The Greeks and the Romans left a legacy in Europe which is evident in European languages, thought, law and minds. Ancient Greece was a collection of city-states, out of which the original form of democracy developed. Athens was the most powerful and developed city, and a cradle of learning from the time of Pericles. Citizens' forums debated and legislated policy of the state, and from here arose some of the most notable classical philosophers, such as Socrates, Plato, and Aristotle, the last of whom taught Alexander the Great.

Through his military campaigns, the king of the kingdom of Macedon, Alexander, spread Hellenistic culture and learning to the banks of the River Indus. But the Roman Republic, strengthened through victory over Carthage in the Punic Wars was rising in the region. Greek wisdom passed into Roman institutions, as Athens itself was absorbed under the banner of the Senate and People of Rome (Senatus Populusque Romanus).

The Romans expanded from Arabia to Britannia. In 44 BC as it approached its height, its leader Julius Caesar was murdered on suspicion of subverting the Republic, to become dictator. In the ensuing turmoil, Octavian usurped the reins of power and fought the Roman Senate. While proclaiming the rebirth of the Republic, he had ushered in the transfer of the Roman state from a republic to an empire, the Roman Empire, which lasted for more than four centuries until the fall of the Western Roman Empire.

Ancient Greece

The Hellenic civilisation was a collection of city-states or poleis with different governments and cultures that achieved notable developments in government, philosophy, science, mathematics, politics, sports, theatre and music.

The most powerful city-states were Athens, Sparta, Thebes, Corinth, and Syracuse. Athens was a powerful Hellenic city-state and governed itself with an early form of direct democracy invented by Cleisthenes; the citizens of Athens voted on legislation and executive bills themselves. Athens was the home of Socrates,[25] Plato, and the Platonic Academy.

The Hellenic city-states established colonies on the shores of the Black Sea and the Mediterranean (Asia Minor, Sicily and Southern Italy in Magna Graecia), and in the 5th century BC their eastward expansions led to retaliation from the Achaemenid Persian Empire. During the Greco-Persian Wars, the Hellenic city-states formed alliances among each other and defeated the Persian Empire at the Battle of Plataea. Some Greek city-states formed the Delian League to continue fighting Persia, but Athens' position as leader of this league led Sparta to form the rival Peloponnesian League. The Peloponnesian Wars ensued, and the Peloponnesian League was victorious. Subsequently, discontent with Spartan hegemony led to the Corinthian War and the defeat of Sparta at the Battle of Leuctra.

Hellenic infighting left Greek city states vulnerable, and Philip II of Macedon united the Greek city states under his control. The son of Philipp II, Alexander the Great, invaded Persia, Egypt and India, and increased contact with people and cultures in these regions marked the beginning of the Hellenistic period.

The rise of Rome

Much of Greek learning was assimilated by the nascent Roman state as it expanded outward from Italy, taking advantage of its enemies' inability to unite: the only challenge to Roman ascent came from the Phoenician colony of Carthage, and its defeats in the three Punic Wars marked the start of Roman hegemony. First governed by kings, then as a senatorial republic (the Roman Republic), Rome finally became an empire at the end of the 1st century BC, under Augustus and his authoritarian successors.

The Roman Empire had its centre in the Mediterranean, controlling all the countries on its shores; the northern border was marked by the Rhine and Danube rivers. Under emperor Trajan (2nd century AD) the empire reached its maximum expansion, controlling approximately 5,900,000 km2 (2,300,000 sq mi) of land surface, including Britain, Romania and parts of Mesopotamia. A period of peace, civilisation and an efficient centralised government in the subject territories ended in the 3rd century, when a series of civil wars undermined Rome's economic and social strength.

In the 4th century, the emperors Diocletian and Constantine were able to slow down the process of decline by splitting the empire into a Western part with a capital in Rome and an Eastern part with the capital in Byzantium, or Constantinople (now Istanbul). Whereas Diocletian severely persecuted Christianity, Constantine declared an official end to state-sponsored persecution of Christians in 313 with the Edict of Milan, thus setting the stage for the Church to become the state church of the Roman Empire in about 380.

Decline of the Roman Empire

The Roman Empire had been repeatedly attacked by invading armies from Northern Europe and in 476, Rome finally fell. Romulus Augustus, the last Emperor of the Western Roman Empire, surrendered to the Germanic King Odoacer. The British historian Edward Gibbon argued in The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire (1776) that the Romans had become decadent, they had lost civic virtue.

Gibbon said that the adoption of Christianity, meant belief in a better life after death, and therefore made people lazy and indifferent to the present. "From the eighteenth century onward", Glen W. Bowersock has remarked,[26] "we have been obsessed with the fall: it has been valued as an archetype for every perceived decline, and, hence, as a symbol for our own fears." It remains one of the greatest historical questions, and has a tradition rich in scholarly interest.

Some other notable dates are the Battle of Adrianople in 378, the death of Theodosius I in 395 (the last time the Roman Empire was politically unified), the crossing of the Rhine in 406 by Germanic tribes after the withdrawal of the legions to defend Italy against Alaric I, the death of Stilicho in 408, followed by the disintegration of the western legions, the death of Justinian I, the last Roman Emperor who tried to reconquer the west, in 565, and the coming of Islam after 632. Many scholars maintain that rather than a "fall", the changes can more accurately be described as a complex transformation.[27] Over time many theories have been proposed on why the Empire fell, or whether indeed it fell at all.

Late Antiquity and Migration Period

When Emperor Constantine had reconquered Rome under the banner of the cross in 312, he soon afterwards issued the Edict of Milan in 313, declaring the legality of Christianity in the Roman Empire. In addition, Constantine officially shifted the capital of the Roman Empire from Rome to the Greek town of Byzantium, which he renamed Nova Roma- it was later named Constantinople ("City of Constantine").

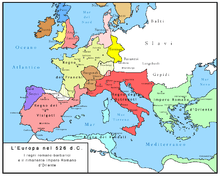

In 395 Theodosius I, who had made Christianity the official religion of the Roman Empire, would be the last emperor to preside over a united Roman Empire, and from thenceforth, the empire would be split into two halves: the Western Roman Empire centred in Ravenna, and the Eastern Roman Empire (later to be referred to as the Byzantine Empire) centred in Constantinople. The Western Roman Empire was repeatedly attacked by Germanic tribes (see: Migration Period), and in 476 finally fell to the Heruli chieftain Odoacer.

Roman authority in the Western part of the Empire collapsed and the western provinces soon were to be dominated by three great powers, the Franks (Merovingian dynasty) in Francia 481–843 AD (covered much of present France and Germany), the Visigothic kingdom 418–711 AD in the Iberian Peninsula and the Ostrogothic kingdom 493–553 AD in Italy and parts of Balkan this kingdom were later replaced by the Kingdom of the Lombards 568–774 AD. These new powers of the west were the continuers of the Roman traditions until they evolved into a merge of Roman and Germanic cultures. In Italy Theodoric the Great began the cultural romanization of the new world he had built, he made Ravenna a center of Romano-Greek culture of art and his court fostered a flowering of literary and the philosophical in Latin. In Iberia, King Chindasuinth created the Visigothic Code. [28]

In Western Europe, a political structure was emerging: in the power vacuum left in the wake of Rome's collapse, localised hierarchies were based on the bond of common people to the land on which they worked. Tithes were paid to the lord of the land, and the lord owed duties to the regional prince. The tithes were used to pay for the state and wars.

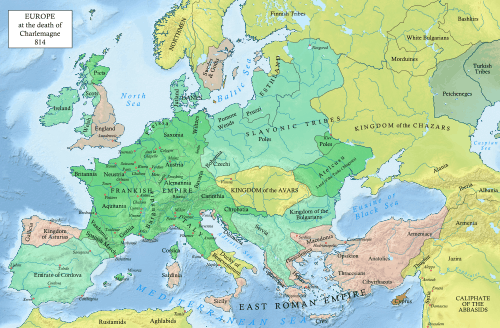

This was the feudal system, in which new princes and kings arose, the greatest of which was the Frank ruler Charlemagne. In 800, Charlemagne, reinforced by his massive territorial conquests, was crowned Emperor of the Romans (Imperator Romanorum) by Pope Leo III, effectively solidifying his power in western Europe.

Charlemagne's reign marked the beginning of a new Germanic Roman Empire in the west, the Holy Roman Empire. Outside his borders, new forces were gathering. The Kievan Rus' were marking out their territory, a Great Moravia was growing, while the Angles and the Saxons were securing their borders.

For the duration of the 6th century, the Eastern Roman Empire was embroiled in a series of deadly conflicts, first with the Persian Sassanid Empire (see Roman–Persian Wars), followed by the onslaught of the arising Islamic Caliphate (Rashidun and Umayyad). By 650, the provinces of Egypt, Palestine and Syria were lost to the Muslim forces, followed by Hispania and southern Italy in the 7th and 8th centuries (see Muslim conquests). The Arab invasion from the east was stopped after the intervention of Bulgarian Empire (see Tervel of Bulgaria).

Middle Ages

The Middle Ages are commonly dated from the fall of the Western Roman Empire (or by some scholars, before that) in the 5th century to the beginning of the early modern period in the 16th century, marked by the rise of nation states, the division of Western Christianity in the Reformation, the rise of humanism in the Italian Renaissance, and the beginnings of European overseas expansion which allowed for the Columbian Exchange.[29]

Many modern European states owe their origins to events unfolding in the Middle Ages; present European political boundaries are, in many regards, the result of the military and dynastic achievements during this tumultuous period.

Byzantium

Many consider Emperor Constantine I (reigned 306–337) to be the first "Byzantine Emperor". It was he who moved the imperial capital in 324 from Nicomedia to Byzantium, re-founded as Constantinople, or Nova Roma ("New Rome").[30] The city of Rome itself had not served as the capital since the reign of Diocletian. Some date the beginnings of the Empire to the reign of Theodosius I (379–395) and Christianity's official supplanting of the pagan Roman religion, or following his death in 395, when the empire was split into two parts, with capitals in Rome and Constantinople. Others place it yet later in 476, when Romulus Augustulus, traditionally considered the last western Emperor, was deposed, thus leaving sole imperial authority with the emperor in the Greek East. Others point to the reorganisation of the empire in the time of Heraclius (c. 620) when Latin titles and usages were officially replaced with Greek versions. In any case, the changeover was gradual and by 330, when Constantine inaugurated his new capital, the process of hellenization and increasing Christianisation was already under way. The Empire is generally considered to have ended after the fall of Constantinople to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Plague of Justinian was a pandemic that afflicted the Byzantine Empire, including its capital Constantinople, in the years 541–542. It is estimated that the Plague of Justinian killed as many as 100 million people across the world.[31][32] It caused Europe's population to drop by around 50% between 541 and 700.[33] It also may have contributed to the success of the Muslim conquests.[34][35]

Early Middle Ages

The Early Middle Ages span roughly five centuries from 500 to 1000.[36]

From the 7th century Byzantine history was greatly affected by the rise of Islam and the Caliphates. Muslim Arabs first invaded historically Roman territory under Abū Bakr, first Caliph of the Rashidun Caliphate, who entered Roman Syria and Roman Mesopotamia. Under Umar, the second Caliph, the Muslims decisively conquered Syria and Mesopotamia, as well as Roman Palestine, Roman Egypt, and parts of Asia Minor and Roman North Africa. This trend continued under Umar's successors and under the Umayyad Caliphate, which conquered the rest of Mediterranean North Africa and most of the Iberian Peninsula. Over the next centuries Muslim forces were able to take further European territory, including Cyprus, Malta, Crete, and Sicily and parts of southern Italy.[37]

The Muslim conquest of Hispania began when the Moors (Berbers and Arabs) invaded the Christian Visigothic kingdom of Hispania in the year 711, under the Berber general Tariq ibn Ziyad. They landed at Gibraltar on 30 April and worked their way northward. Tariq's forces were joined the next year by those of his Arab superior, Musa ibn Nusair. During the eight-year campaign most of the Iberian Peninsula was brought under Muslim rule – save for small areas in the northwest (Asturias) and largely Basque regions in the Pyrenees. In 711 the Visigothic Hispania, was very weakened because it was immersed in a serious internal crisis caused by a war of succession to the throne, starring two Visigoth suitors. The Muslims took advantage of the crisis that crossed the Hispano-Visigothic society, to carry out their conquests. This territory, under the Arab name Al-Andalus, became part of the expanding Umayyad empire.

The unsuccessful second siege of Constantinople (717) weakened the Umayyad dynasty and reduced their prestige. In 722 Don Pelayo, a nobleman of Visigothic origin, formed an army of 300 Astur soldiers, to confront Munuza's Muslim troops. In the battle of Covadonga, the Astures defeated the Arab-Moors, who decided to retire. The Christian victory marked the beginning of the Reconquista and the establishment of the Kingdom of Asturias, whose first sovereign was Don Pelayo. The conquerors intended to continue their expansion in Europe and move northeast across the Pyrenees, but were defeated by the Frankish leader Charles Martel at the Battle of Poitiers in 732. The Umayyads were overthrown in 750 by the 'Abbāsids and most of the Umayyad clan massacred.

A surviving Umayyad prince, Abd-ar-rahman I, escaped to Spain and founded a new Umayyad dynasty in the Emirate of Cordoba, (756). Charles Martel's son, Pippin the Short retook Narbonne, and his grandson Charlemagne established the Marca Hispanica across the Pyrenees in part of what today is Catalonia, reconquering Girona in 785 and Barcelona in 801. The Umayyads in Spain proclaimed themselves caliphs in 929. During this period, most of Europe was Christianised, and the "Dark Ages" following the fall of Rome took place. The establishment of the Frankish Empire by the 9th century led to the Carolingian Renaissance on the continent.

Feudal Christendom

The Holy Roman Empire emerged around 800, as Charlemagne, king of the Franks, was crowned by the pope as emperor. His empire based in modern France, the Low Countries and Germany expanded into modern Hungary, Italy, Bohemia, Lower Saxony and Spain. He and his father received substantial help from an alliance with the Pope, who wanted help against the Lombards. The pope was officially a vassal of the Byzantine Empire, but the Byzantine emperor did (could do) nothing against the Lombards.

To the east, Bulgaria was established in 681 and became the first Slavic country. The powerful Bulgarian Empire was the main rival of Byzantium for control of the Balkans for centuries and from the 9th century became the cultural centre of Slavic Europe. The Empire created the Cyrillic script during the 10th century AD, at the Preslav Literary School. Two states, Great Moravia and Kievan Rus', emerged among the Slavic peoples respectively in the 9th century. In the late 9th and 10th centuries, northern and western Europe felt the burgeoning power and influence of the Vikings who raided, traded, conquered and settled swiftly and efficiently with their advanced seagoing vessels such as the longships. The Hungarians pillaged mainland Europe, the Pechenegs raided Bulgaria, Rus States and the Arab states. In the 10th century independent kingdoms were established in Central Europe, for example, Poland and Kingdom of Hungary. Hungarians had stopped their pillaging campaigns; prominent also included Croatia and Serbia in the Balkans. The subsequent period, ending around 1000, saw the further growth of feudalism, which weakened the Holy Roman Empire.

In the eastern Europe, Volga Bulgaria became an Islamic state in 921, after Almış I converted to Islam under the missionary efforts of Ahmad ibn Fadlan.[38]

Slavery in early medieval Europe had mostly died out in western Europe about the year 1000 AD, replaced by serfdom. It lingered longer in England and in peripheral areas linked to the Muslim world, where slavery continued to flourish. Church rules suppressed slavery of Christians. Most historians argue the transition was quite abrupt around 1000, but some see a gradual transition from about 300 to 1000.[39]

High Middle Ages

The slumber of the Dark Ages was shaken by renewed crisis in the Church. In 1054, the East–West Schism, an insoluble split, occurred between the two remaining Christian seats in Rome and Constantinople (nowadays Istanbul).

The High Middle Ages of the 11th, 12th, and 13th centuries show a rapidly increasing population of Europe, which caused great social and political change from the preceding era. By 1250, the robust population increase greatly benefited the economy, reaching levels it would not see again in some areas until the 19th century. From about the year 1000 onwards, Western Europe saw the last of the barbarian invasions and became more politically organized. The Vikings had settled in Britain, Ireland, France and elsewhere, whilst Norse Christian kingdoms were developing in their Scandinavian homelands. The Magyars had ceased their expansion in the 10th century, and by the year 1000, the Roman Catholic Apostolic Kingdom of Hungary was recognised in central Europe. With the brief exception of the Mongol invasions, major barbarian incursions ceased.

In the 11th century, populations north of the Alps began to settle new lands, some of which had reverted to wilderness after the end of the Roman Empire. In what is known as the "great clearances", vast forests and marshes of Europe were cleared and cultivated. At the same time settlements moved beyond the traditional boundaries of the Frankish Empire to new frontiers in Europe, beyond the Elbe river, tripling the size of Germany in the process. Crusaders founded European colonies in the Levant, the majority of the Iberian Peninsula was conquered from the Muslims, and the Normans colonised southern Italy, all part of the major population increase and resettlement pattern.

The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and artistic works. the most famous are the great cathedrals as expressions of Gothic architecture, which evolved from Romanesque architecture. This age saw the rise of modern nation-states in Western Europe and the ascent of the famous Italian city-states, such as Florence and Venice. The influential popes of the Catholic Church called volunteer armies from across Europe to a series of Crusades against the infidels, who occupied the Holy Land. The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle led Thomas Aquinas and other thinkers to develop the philosophy of Scholasticism.

A divided church

The Great Schism between the Western (Catholic) and Eastern (Orthodox) Christian Churches was sparked in 1054 by Pope Leo IX asserting authority over three of the seats in the Pentarchy, in Antioch, Jerusalem and Alexandria. Since the mid-8th century, the Byzantine Empire's borders had been shrinking in the face of Islamic expansion. Antioch had been wrested back into Byzantine control by 1045, but the resurgent power of the Roman successors in the West claimed a right and a duty for the lost seats in Asia and Africa. Pope Leo sparked a further dispute by defending the filioque clause in the Nicene Creed which the West had adopted customarily. The Orthodox today state that the XXVIIIth Canon of the Council of Chalcedon explicitly proclaimed the equality of the Bishops of Rome and Constantinople. The Orthodox also state that the Bishop of Rome has authority only over his own diocese and does not have any authority outside his diocese. There were other less significant catalysts for the Schism however, including variance over liturgical. The Schism of Roman Catholic and Orthodox followed centuries of estrangement between Latin and Greek worlds.

Further changes were set afoot with a redivision of power in Europe. William the Conqueror, a Duke of Normandy invaded England in 1066. The Norman Conquest was a pivotal event in English history for several reasons. This linked England more closely with continental Europe through the introduction of a Norman aristocracy, thereby lessening Scandinavian influence. It created one of the most powerful monarchies in Europe and engendered a sophisticated governmental system. Being based on an island, moreover, England was to develop a powerful navy and trade relationships that would come to constitute a vast part of the world including India, Australia, New Zealand, Canada and many key naval strategic points like Bermuda, Suez, Hong Kong and especially Gibraltar. These strategic advantages grew and were to prove decisive until after the Second World War.

Holy wars

After the East–West Schism, Western Christianity was adopted by newly created kingdoms of Central Europe: Poland, Hungary and Bohemia. The Roman Catholic Church developed as a major power, leading to conflicts between the Pope and Emperor. The geographic reach of the Roman Catholic Church expanded enormously due to conversions of pagan kings (Scandinavia, Lithuania, Poland, Hungary), Christian Reconquista of Al-Andalus, and crusades. Most of Europe was Roman Catholic in the 15th century.

Early signs of the rebirth of civilisation in western Europe began to appear in the 11th century as trade started again in Italy, leading to the economic and cultural growth of independent city-states such as Venice and Florence; at the same time, nation-states began to take form in places such as France, England, Spain, and Portugal, although the process of their formation (usually marked by rivalry between the monarchy, the aristocratic feudal lords and the church) actually took several centuries. These new nation-states began writing in their own cultural vernaculars, instead of the traditional Latin. Notable figures of this movement would include Dante Alighieri and Christine de Pizan (born Christina da Pizzano), the former writing in Italian, and the latter, although an Italian (Venice), relocated to France, writing in French. (See Reconquista for the latter two countries.) On the other hand, the Holy Roman Empire, essentially based in Germany and Italy, further fragmented into a myriad of feudal principalities or small city states, whose subjection to the emperor was only formal.

The 13th and 14th century, when the Mongol Empire came to power, is often called the Age of the Mongols. Mongol armies expanded westward under the command of Batu Khan. Their western conquests included almost all of Russia (save Novgorod, which became a vassal),[40] Kipchak-Cuman Confederation, Hungary, and Poland (which had remained sovereign state). Mongolian records indicate that Batu Khan was planning a complete conquest of the remaining European powers, beginning with a winter attack on Austria, Italy and Germany, when he was recalled to Mongolia upon the death of Great Khan Ögedei. Most historians believe only his death prevented the complete conquest of Europe.[citation needed] The areas of the Eastern Europe and most of Central Asia that were under direct Mongol rule would become known as the Golden Horde. Under Uzbeg Khan, Islam would become the official religion of the country in the early 14th century.[41] The invading Mongols, together with their mostly Turkic subjects, would become known as Tatars. In Russia, the Tatars ruled the various states of the Rus' through vassalage for over 300 years.

Late Middle Ages

The Late Middle Ages span the 14th and 15th centuries. Around 1300, centuries of European prosperity and growth came to a halt. A series of famines and plagues, such as the Great Famine of 1315–1317 and the Black Death, reduced the population by as much as half according to some estimates. Along with depopulation came social unrest and endemic warfare. France and England experienced serious peasant risings: the Jacquerie, the Peasants' Revolt, and the Hundred Years' War. To add to the many problems of the period, the unity of the Catholic Church was shattered by the Great Schism. Collectively these events are sometimes called the Crisis of the Late Middle Ages.[42]

Beginning in the 14th century, the Baltic Sea became one of the most important trade routes. The Hanseatic League, an alliance of trading cities, facilitated the absorption of vast areas of Poland, Lithuania and other Baltic states into trade with other European countries. This fed the growth of powerful states in this part of Europe including Poland-Lithuania, Hungary, Bohemia, and Muscovy later on. The conventional end of the Middle Ages is usually associated with the fall of the city Constantinople and of the Byzantine Empire to the Ottoman Turks in 1453. The Turks made the city the capital of their Ottoman Empire, which lasted until 1922 and included Egypt, Syria and most of the Balkans. The Ottoman wars in Europe, also sometimes referred to as the Turkish wars, marked an essential part of the history of the continent as a whole.

Early modern Europe

The Early Modern period spans the centuries between the Middle Ages and the Industrial Revolution, roughly from 1500 to 1800, or from the discovery of the New World in 1492 to the French Revolution in 1789. The period is characterised by the rise to importance of science and increasingly rapid technological progress, secularised civic politics and the nation state. Capitalist economies began their rise, beginning in northern Italian republics such as Genoa. The early modern period also saw the rise and dominance of the economic theory of mercantilism. As such, the early modern period represents the decline and eventual disappearance, in much of the European sphere, of feudalism, serfdom and the power of the Catholic Church. The period includes the Protestant Reformation, the disastrous Thirty Years' War, the European colonisation of the Americas and the European witch-hunts.

Renaissance

Despite these crises, the 14th century was also a time of great progress within the arts and sciences. A renewed interest in ancient Greek and Roman texts led to what has later been termed the Italian Renaissance.

The Renaissance was a cultural movement that profoundly affected European intellectual life in the early modern period. Beginning in Italy, and spreading to the north, west and middle Europe during a cultural lag of some two and a half centuries, its influence affected literature, philosophy, art, politics, science, history, religion, and other aspects of intellectual enquiry.

The Italian Petrarch (Francesco di Petracco), deemed the first full-blooded Humanist, wrote in the 1330s: "I am alive now, yet I would rather have been born in another time." He was enthusiastic about Greek and Roman antiquity. In the 15th and 16th centuries the continuing enthusiasm for the ancients was reinforced by the feeling that the inherited culture was dissolving and here was a storehouse of ideas and attitudes with which to rebuild. Matteo Palmieri wrote in the 1430s: "Now indeed may every thoughtful spirit thank god that it has been permitted to him to be born in a new age." The renaissance was born: a new age where learning was very important.

The Renaissance was inspired by the growth in study of Latin and Greek texts and the admiration of the Greco-Roman era as a golden age. This prompted many artists and writers to begin drawing from Roman and Greek examples for their works, but there was also much innovation in this period, especially by multi-faceted artists such as Leonardo da Vinci. The Humanists saw their repossession of a great past as a Renaissance—a rebirth of civilization itself.[43]

Important political precedents were also set in this period. Niccolò Machiavelli's political writing in The Prince influenced later absolutism and real-politik. Also important were the many patrons who ruled states and used the artistry of the Renaissance as a sign of their power.

In all, the Renaissance could be viewed as an attempt by intellectuals to study and improve the secular and worldly, both through the revival of ideas from antiquity, and through novel approaches to thought—the immediate past being too "Gothic" in language, thought and sensibility.

During this period, Spain experienced the epoch of greatest splendor cultural of its history. This epoch is known as the Spanish Golden age and took place between the sixteenth and seventeenth.

Exploration and trade

Toward the end of the period, an era of discovery began. The growth of the Ottoman Empire, culminating in the fall of Constantinople in 1453, cut off trading possibilities with the east. Western Europe was forced to discover new trading routes, as happened with Columbus's travel to the Americas in 1492, and Vasco da Gama's circumnavigation of India and Africa in 1498.

The numerous wars did not prevent European states from exploring and conquering wide portions of the world, from Africa to Asia and the newly discovered Americas. In the 15th century, Portugal led the way in geographical exploration along the coast of Africa in search for a maritime route to India, followed by Spain near the close of the 15th century; dividing their exploration of world according to the Treaty of Tordesillas of 1494.[44] They were the first states to set up colonies in America and trading posts (factories) along the shores of Africa and Asia, establishing the first direct European diplomatic contacts with Southeast Asian states in 1511, China in 1513 and Japan in 1542. In 1552, Russian tsar Ivan the Terrible conquered two major Tatar khanates, Khanate of Kazan and the Astrakhan Khanate, and the Yermak's voyage of 1580 led to the annexation of the Tatar Siberian Khanate into Russia; the Russians would soon after conquer the rest of Siberia. Oceanic explorations were soon followed by France, England and the Netherlands, who explored the Portuguese and Spanish trade routes into the Pacific Ocean, reaching Australia in 1606[45] and New Zealand in 1642.

Reformation

Spreading through Europe with the development of printing press, knowledge challenged traditional doctrines in science and theology. Simultaneously Protestant Reformation under German Martin Luther questioned Papal authority. The most common dating begins in 1517, when Luther published The Ninety-Five Theses, and concludes in 1648 with the Treaty of Westphalia that ended years of European religious wars.[46]

During this period corruption in the Catholic Church led to a sharp backlash in the Protestant Reformation. It gained many followers especially among princes and kings seeking a stronger state by ending the influence of the Catholic Church. Figures other than Martin Luther began to emerge as well like John Calvin whose Calvinism had influence in many countries and King Henry VIII of England who broke away from the Catholic Church in England and set up the Anglican Church (contrary to popular belief, this is only half true; his daughter Queen Elizabeth finished the organization of the church). These religious divisions brought on a wave of wars inspired and driven by religion but also by the ambitious monarchs in Western Europe who were becoming more centralised and powerful.

The Protestant Reformation also led to a strong reform movement in the Catholic Church called the Counter-Reformation, which aimed to reduce corruption as well as to improve and strengthen Catholic Dogma. Two important groups in the Catholic Church who emerged from this movement were the Jesuits, who helped keep Spain, Portugal, Poland and other European countries within the Catholic fold, and the Oratorians of St Philip Neri, who ministered to the faithful in Rome, restoring their confidence in the Church of Jesus Christ that subsisted substantially in the Church of Rome. Still, the Catholic Church was somewhat weakened by the Reformation, portions of Europe were no longer under its sway and kings in the remaining Catholic countries began to take control of the Church institutions within their kingdoms.

Unlike many European countries, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and Hungary, were more tolerant. While still enforcing the predominance of Catholicism they continued to allow the large religious minorities to maintain their faiths, traditions and customs. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth became divided between Catholics, Protestants, Orthodox, Jews and a small Muslim population.

Another important development in this period was the growth of pan-European sentiments. Eméric Crucé (1623) came up with the idea of the European Council, intended to end wars in Europe; attempts to create lasting peace were no success, although all European countries (except the Russian and Ottoman Empires, regarded as foreign) agreed to make peace in 1518 at the Treaty of London. Many wars broke out again in a few years. The Reformation also made European peace impossible for many centuries.

Another development was the idea of 'European superiority'. The ideal of civilisation was taken over from the ancient Greeks and Romans: discipline, education and living in the city were required to make people civilised; Europeans and non-Europeans were judged for their civility, and Europe regarded itself as superior to other continents. There was a movement by some such as Montaigne that regarded the non-Europeans as a better, more natural and primitive people. Post services were founded all over Europe, which allowed a humanistic interconnected network of intellectuals across Europe, despite religious divisions. However, the Roman Catholic Church banned many leading scientific works; this led to an intellectual advantage for Protestant countries, where the banning of books was regionally organised. Francis Bacon and other advocates of science tried to create unity in Europe by focusing on the unity in nature.1 In the 15th century, at the end of the Middle Ages, powerful sovereign states were appearing, built by the New Monarchs who were centralising power in France, England, and Spain. On the other hand the Parliament in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth grew in power, taking legislative rights from the Polish king. The new state power was contested by parliaments in other countries especially England. New kinds of states emerged which were co-operation agreements between territorial rulers, cities, farmer republics and knights.

Mercantilism and colonial expansion

The Iberian states (Spain and Portugal) were able to dominate New World (American) colonial activity in the 16th century. The Spanish constituted the first global empire and during the sixteenth century and the first half of the seventeenth century, Spain was the most powerful nation in the world, but was increasingly challenged by British, French, and the short-lived Dutch and Swedish colonial efforts of the 17th and 18th centuries. New forms of trade and expanding horizons made new forms of government, law and eco nomics necessary.

Colonial expansion continued in the following centuries (with some setbacks, such as successful wars of independence in the British American colonies and then later Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, and others amid the European turmoil of the Napoleonic Wars). Spain had control of a large part of North America, all of Central America and a great part of South America, the Caribbean and the Philippines; Britain took the whole of Australia and New Zealand, most of India, and large parts of Africa and North America; France held parts of Canada and India (nearly all of which was lost to Britain in 1763), Indochina, large parts of Africa and Caribbean islands; the Netherlands gained the East Indies (now Indonesia) and islands in the Caribbean; Portugal obtained Brazil and several territories in Africa and Asia; and later, powers such as Germany, Belgium, Italy and Russia acquired further colonies.

This expansion helped the economy of the countries owning them. Trade flourished, because of the minor stability of the empires. By the late 16th century, American silver accounted for one-fifth of the Spain's total budget.[47] The European countries fought wars that were largely paid for by the money coming in from the colonies. Nevertheless, the profits of the slave trade and of plantations of the West Indies, then the most profitable of all the British colonies, amounted to less than 5% of the British Empire's economy (but was generally more profitable) at the time of the Industrial Revolution in the late 18th century.

Crisis of the 17th century

The 17th century was an era of crisis.[48][49] Many historians have rejected the idea, while others promote it an invaluable insight into the warfare, politics, economics,[50] and even art.[51] The Thirty Years' War (1618–1648) focused attention on the massive horrors that wars could bring to entire populations.[52] The 1640s in particular saw more state breakdowns around the world than any previous or subsequent period.[48][49] The Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth, the largest state in Europe, temporarily disappeared. In addition, there were secessions and upheavals in several parts of the Spanish empire, the world's first global empire. In Britain the entire Stuart monarchy (England, Scotland, Ireland, and its North American colonies) rebelled. Political insurgency and a spate of popular revolts seldom equalled shook the foundations of most states in Europe and Asia. More wars took place around the world in the mid-17th century than in almost any other period of recorded history. The crises spread far beyond Europe—for example Ming China, the most populous state in the world, collapsed. Across the Northern Hemisphere, the mid-17th century experienced almost unprecedented death rates. Parker suggests that environmental factors may have been in part to blame, especially global cooling.[53][54]

Enlightenment

Throughout the early part of this period, capitalism (through Mercantilism) was replacing feudalism as the principal form of economic organisation, at least in the western half of Europe. The expanding colonial frontiers resulted in a Commercial Revolution. The period is noted for the rise of modern science and the application of its findings to technological improvements, which culminated in the Industrial Revolution.

The Reformation had profound effects on the unity of Europe. Not only were nations divided one from another by their religious orientation, but some states were torn apart internally by religious strife, avidly fostered by their external enemies. France suffered this fate in the 16th century in the series of conflicts known as the French Wars of Religion, which ended in the triumph of the Bourbon Dynasty. England avoided this fate for a while and settled down under Elizabeth to a moderate Anglicanism. Much of modern day Germany was made up of numerous small sovereign states under the theoretical framework of the Holy Roman Empire, which was further divided along internally drawn sectarian lines. The Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth is notable in this time for its religious indifference and a general immunity to the horrors of European religious strife.

The Thirty Years' War was fought between 1618 and 1648, principally on the territory of today's Germany, and involved most of the major European powers. Beginning as a religious conflict between Protestants and Catholics in Bohemia, it gradually developed into a general war involving much of Europe, for reasons not necessarily related to religion.[55] The major impact of the war, in which mercenary armies were extensively used, was the devastation of entire regions scavenged bare by the foraging armies. Episodes of widespread famine and disease devastated the population of the German states and, to a lesser extent, the Low Countries, Bohemia and Italy, while bankrupting many of the regional powers involved. Between one-fourth and one-third of the German population perished from direct military causes or from illness and starvation related to the war.[56] The war lasted for thirty years, but the conflicts that triggered it continued unresolved for a much longer time.

After the Peace of Westphalia which ended the war in favour of nations deciding their own religious allegiance, Absolutism became the norm of the continent, while parts of Europe experimented with constitutions foreshadowed by the English Civil War and particularly the Glorious Revolution. European military conflict did not cease, but had less disruptive effects on the lives of Europeans. In the advanced northwest, the Enlightenment gave a philosophical underpinning to the new outlook, and the continued spread of literacy, made possible by the printing press, created new secular forces in thought. Again, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth would be an exception to this rule, with its unique quasi-democratic Golden Freedom. But in 1648 beginning of the Khmelnytsky Uprising in Ukraine, at this time in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, which continues until 1654, and results is concluded in the city of Pereyaslav during the meeting between the Cossacks of the Zaporozhian Host and Tsar Alexey I of Russia the Treaty of Pereyaslav.

Europe in 16th and 17th century was an arena of conflict for domination in the continent between Sweden, the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire. This period saw a gradual decline of these three powers which were eventually replaced by new enlightened absolutist monarchies, Russia, Prussia and Austria. By the turn of the 19th century they became new powers, having divided Poland between them, with Sweden and Turkey having experienced substantial territorial losses to Russia and Austria respectively as well as pauperisation. Numerous Polish Jews emigrated to France, Germany and America, founding Jewish communities in places where they had been expelled from during the Middle Ages.

Frederick the Great, king of Prussia 1740-86, modernized the Prussian army, introduced new tactical and strategic concepts, fought mostly successful wars and doubled the size of Prussia. Frederick had a rationale based on Enlightenment thought: he fought total wars for limited objectives. The goal was to convince rival kings that it was better to negotiate and make peace than to fight him.[57][58]

From revolution to imperialism

The "long nineteenth century", from 1789 to 1914 sees the drastic social, political and economic changes initiated by the Industrial Revolution, the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars, and following the reorganisation of the political map of Europe at the Congress of Vienna in 1815, the rise of Nationalism, the rise of the Russian Empire and the peak of the British Empire, paralleled by the decline of the Ottoman Empire. Finally, the rise of the German Empire and the Austro-Hungarian Empire initiated the course of events that culminated in the outbreak of the First World War in 1914.

Industrial Revolution

The Industrial Revolution was a period in the late 18th century and early 19th century when major changes in agriculture, manufacturing, and transport affected socioeconomic and cultural conditions in Britain and subsequently spread throughout Europe and North America and eventually the world, a process that continues as industrialisation. It started in England and Scotland in the mid-18th century with the mechanisation of the textile industries, the development of iron-making techniques and the increased use of refined coal. Once started it spread. Trade expansion was enabled by the introduction of canals, improved roads and railways. The introduction of steam power (fuelled primarily by coal) and powered machinery (mainly in textile manufacturing) underpinned the dramatic increases in production capacity.[59] The development of all-metal machine tools in the first two decades of the 19th century facilitated the manufacture of more production machines for manufacturing in other industries. The effects spread throughout Western Europe and North America during the 19th century, eventually affecting most of the world. The impact of this change on society was enormous.[60]

Political revolution

The American Revolution (1775-1783) was the first successful revolt of a colony from a European power. It proclaimed, in the words of Thomas Jefferson, the Enlightenment position that "all men are created equal." It rejected aristocracy and set up a republican form of government under George Washington that attracted worldwide attention.[61]

The French Revolution (1789-1804) was a product of the same democratic forces in the Atlantic World and had an even greater impact.[62] French historian François Aulard says:

- From the social point of view, the Revolution consisted in the suppression of what was called the feudal system, in the emancipation of the individual, in greater division of landed property, the abolition of the privileges of noble birth, the establishment of equality, the simplification of life.... The French Revolution differed from other revolutions in being not merely national, for it aimed at benefiting all humanity."[63]

French intervention in the American Revolutionary War had nearly bankrupted the state. After repeated failed attempts at financial reform, King Louis XVI had to convene the Estates-General, a representative body of the country made up of three estates: the clergy, the nobility, and the commoners. The third estate, joined by members of the other two, declared itself to be a National Assembly and swore an oath not to dissolve until France had a constitution and created, in July, the National Constituent Assembly. At the same time the people of Paris revolted, famously storming the Bastille prison on 14 July 1789.

At the time the assembly wanted to create a constitutional monarchy, and over the following two years passed various laws including the Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen, the abolition of feudalism, and a fundamental change in the relationship between France and Rome. At first the king agreed with these changes and enjoyed reasonable popularity with the people. As anti-royalism increased along with threat of foreign invasion, the king tried to flee and join France's enemies. He was captured and on 12 January 1793, having been convicted of treason, he was guillotined.

On 20 September 1792 the National Convention abolished the monarchy and declared France a republic. Due to the emergency of war the National Convention created the Committee of Public Safety, controlled by Maximilien de Robespierre of the Jacobin Club, to act as the country's executive. Under Robespierre the committee initiated the Reign of Terror, during which up to 40,000 people were executed in Paris, mainly nobles, and those convicted by the Revolutionary Tribunal, often on the flimsiest of evidence. Elsewhere in the country, counter-revolutionary insurrections were brutally suppressed. The regime was overthrown in the coup of 9 Thermidor (27 July 1794) and Robespierre was executed. The regime which followed ended the Terror and relaxed Robespierre's more extreme policies.

Napoleon Bonaparte was France's most successful general in the Revolutionary wars, having conquered large parts of Italy and forced the Austrians to sue for peace. In 1799 he returned from Egypt and on 18 Brumaire (9 November) overthrew the government, replacing it with the Consulate, in which he was First Consul. On 2 December 1804, after a failed assassination plot, he crowned himself Emperor. In 1805, Napoleon planned to invade Britain, but a renewed British alliance with Russia and Austria (Third Coalition), forced him to turn his attention towards the continent, while at the same time failure to lure the superior British fleet away from the English Channel, ending in a decisive French defeat at the Battle of Trafalgar on 21 October put an end to hopes of an invasion of Britain. On 2 December 1805, Napoleon defeated a numerically superior Austro-Russian army at Austerlitz, forcing Austria's withdrawal from the coalition (see Treaty of Pressburg) and dissolving the Holy Roman Empire. In 1806, a Fourth Coalition was set up. On 14 October Napoleon defeated the Prussians at the Battle of Jena-Auerstedt, marched through Germany and defeated the Russians on 14 June 1807 at Friedland. The Treaties of Tilsit divided Europe between France and Russia and created the Duchy of Warsaw.

On 12 June 1812 Napoleon invaded Russia with a Grande Armée of nearly 700,000 troops. After the measured victories at Smolensk and Borodino Napoleon occupied Moscow, only to find it burned by the retreating Russian army. He was forced to withdraw. On the march back his army was harassed by Cossacks, and suffered disease and starvation. Only 20,000 of his men survived the campaign. By 1813 the tide had begun to turn from Napoleon. Having been defeated by a seven nation army at the Battle of Leipzig in October 1813, he was forced to abdicate after the Six Days' Campaign and the occupation of Paris. Under the Treaty of Fontainebleau he was exiled to the island of Elba. He returned to France on 1 March 1815 (see Hundred Days), raised an army, but was comprehensively defeated by a British and Prussian force at the Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

Nations rising

After the defeat of revolutionary France, the other great powers tried to restore the situation which existed before 1789. In 1815 at the Congress of Vienna, the major powers of Europe managed to produce a peaceful balance of power among the various European empires. This was known as the Metternich system. However, their efforts were unable to stop the spread of revolutionary movements: the middle classes had been deeply influenced by the ideals of the French revolution, the Industrial Revolution brought important economical and social changes, the lower classes started to be influenced by socialist, communist and anarchistic ideas (especially those summarised by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels in The Communist Manifesto), and the political ideas of the new capitalists became liberalism. Further instability came from the formation of several nationalist movements (in Germany, Italy, Poland, Hungary, etc.) seeking national unification and/or liberation from foreign rule. As a result, the period between 1815 and 1871 saw a large number of revolutionary attempts and independence wars. One of the biggest revolutions was in Greece, which had been under Ottoman rule until the early 19th century. On 25 March 1821 (the day of Annunciation in the Greek Orthodox Church), the Greeks rebelled and declared their independence, led by Theodore Kolokotronis, but did not win the resulting war until 1829. The major European powers saw the Greek war of independence, with its accounts of Turkish atrocities, in a romantic light. Napoleon III, nephew of Napoleon I, returned from exile in the United Kingdom in 1848 to be elected to the French parliament, and then as "Prince President" in a coup d'état elected himself Emperor, a move approved later by a large majority of the French electorate. He helped in the unification of Italy by fighting the Austrian Empire and joined the Crimean War on the side of the United Kingdom and the Ottoman Empire against Russia. His empire collapsed after being defeated in the Franco-Prussian War, during which Napoleon III himself was captured. In Versailles, King Wilhelm I of Prussia was proclaimed Emperor of Germany, and the modern state of Germany was born. Even though most revolutions in this period were defeated, most European states had become constitutional (rather than absolute) monarchies by 1871, and Germany and Italy had developed into nation-states. The 19th century also saw the British Empire emerge as the world's first global power due in a large part to the Industrial Revolution and victory in the Napoleonic Wars.

Imperialism

Colonial empires were the product of the European Age of Discovery from the 15th century. The initial impulse behind these dispersed maritime empires and those that followed was trade, driven by the new ideas and the capitalism that grew out of the Renaissance. Both the Portuguese Empire and Spanish Empire quickly grew into the first global political and economic systems with territories spread around the world.

Subsequent major European colonial empires included the French, Dutch, and British empires. The latter, consolidated during the period of British maritime hegemony in the 19th century, became the largest empire in history because of the improved transportation technologies of the time. At its height, the British Empire covered a quarter of the Earth's land area and comprised a quarter of its population. Other European countries, such as Belgium, Germany, and Italy, pursued colonial empires as well (mostly in Africa), but they were comparatively smaller than those mentioned above. By the 1860s, the Russian Empire became the largest contiguous state in the world, and its later successors (first the Soviet Union, then the Russian Federation) continued to be so ever since. Today, Russia has nine time zones, stretching slightly over half the world's longitude.

By the mid-19th century, the Ottoman Empire had declined enough to become a target for the others (see History of the Balkans). This instigated the Crimean War in 1854 and began a tenser period of minor clashes among the globe-spanning empires of Europe that eventually set the stage for the First World War. In the second half of the 19th century, the Kingdom of Sardinia and the Kingdom of Prussia carried out a series of wars that resulted in the creation of Italy and Germany as nation-states, significantly changing the balance of power in Europe. From 1870, Otto von Bismarck engineered a German hegemony of Europe that put France in a critical situation. It slowly rebuilt its relationships, seeking alliances with Russia and Britain to control the growing power of Germany. In this way, two opposing sides—the Triple Alliance of 1882 and the Triple Entente of 1907—formed in Europe, improving their military forces and alliances year-by-year.

World Wars and Cold War

The "short twentieth century", from 1914 to 1991, included the First World War, the Second World War and the Cold War. The First World War drastically changed the map of Europe, ending four major land empires (the Russian, German, Austro-Hungarian and Ottoman empires) and leading to the creation of nation-states across Central and Eastern Europe. The October Revolution in Russia and the resulting civil war led to the creation of the Soviet Union and the rise of the international communist movement. Later, the Great Depression caused fascist dictatorships to take power across central Europe, leading to the Second World War. That war ended with the division of Europe between East and West, and also caused the gradual collapse of several colonial empires, with the British and French (and other) empires ending in decolonisation – the independence of new states from 1947 to 1970. The fall of Soviet Communism between 1989 and 1991 left the West as the winner of the Cold War and enabled the reunification of Germany and an accelerated process of a European integration that is continuing today, but with German economic dominance.

First World War

After the relative peace of most of the 19th century, the rivalry between European powers, compounded by a rising nationalism among ethnic groups, exploded in August 1914, when the First World War started. Over 65 million European soldiers were mobilised from 1914–1918; 20 million soldiers and civilians died, and 21 million were seriously wounded.[64] On one side were Germany, Austria-Hungary, the Ottoman Empire and Bulgaria (the Central Powers/Triple Alliance), while on the other side stood Serbia and the Triple Entente – the loose coalition of France, Britain and Russia, which were joined by Italy in 1915, Romania in 1916 and by the United States in 1917. The Western Front involved especially brutal combat without any territorial gains by either side. Single battles like Verdun and the Some killed hundreds of thousands of men while leaving the stalemate unchanged. Heavy artillery and machine guns caused most of the casualties, supplemented by poison gas. Czarist Russia collapsed in the February Revolution of 1917 and Germany claimed victory on the Eastern Front. After eight months of liberal rule, the October Revolution brought Vladimir Lenin and the Bolsheviks to power, leading to the creation of the Soviet Union in place of the disintegrated Russian Empire. With American entry into the war in 1917 on the Allied side, and the failure of Germany's spring 1918 offensive, Germany had run out of manpower, while an average of 10,000 American troops were arriving in France every day in summer 1918. Germany's allies, Austria-Hungary and the Ottoman Empire, surrendered with their empires dissolved. Germany finally surrendered as well on 11 November 1918.[65][66] Historians still debate who was to blame for the war, but the victors forced Germany to admit guilt and pay war reparations.

The Allies had much more potential wealth they could spend on the war. One estimate (using 1913 US dollars) is that the Allies spent $58 billion on the war and the Central Powers only $25 billion. Among the Allies, Britain spent $21 billion and the U.S. $17 billion; among the Central Powers Germany spent $20 billion.[67]

Paris Peace Conference

The world war was settled by the victors at the Paris Peace Conference in 1919. Two dozen nations sent delegations, and there were many nongovernmental groups, but the defeated powers were not invited.[68]

The "Big Four" were President Woodrow Wilson of the United States, Prime Minister David Lloyd George of Great Britain, George Clemenceau of France, and, of least importance, Italian Prime Minister Vittorio Orlando. They met together informally 145 times and made all the major decisions, which in turn were ratified by the others.[69]

The major decisions were the creation of the League of Nations; the six peace treaties with defeated enemies, most notable the Treaty of Versailles with Germany; the awarding of German and Ottoman overseas possessions as "mandates", chiefly to Britain and France; and the drawing of new national boundaries (sometimes with plebiscites) to better reflect the forces of nationalism.[70][71]

Interwar

In the Treaty of Versailles (1919) the winners imposed relatively hard conditions on Germany and recognised the new states (such as Poland, Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Austria, Yugoslavia, Finland, Estonia, Latvia, Lithuania) created in central Europe from the defunct German, Austro-Hungarian and Russian empires, based on national (ethnic) self-determination. It was a peaceful era with a few small wars before 1922 such as the Polish–Soviet War (1919–1921). Prosperity was widespread, and the major cities sponsored a youth culture called the "Roaring Twenties" that was often featured in the cinema, which attracted very large audiences.