Eureka Jack

The Eureka Jack is the name given to a specimen Union Jack reportedly hoisted beneath the Eureka flag at the 1854 Battle of the Eureka Stockade in Ballarat, Victoria, Australia.[1]

What happened to the Eureka Jack?

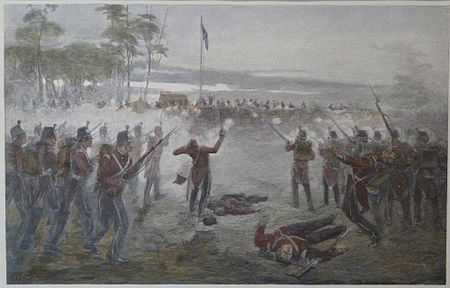

The Eureka flag was being flown at the stockade enclosure at the time of the battle on 3 December 1854. During the fighting, the war ravenged flag pole collapsed as Constable John King climbed to capture the enemy colours, which were then trampled on, hacked with swords and peppered with bullets by colonial troops.

When the first reports of the clash appeared in Melbourne the next day, readers of The Argus newspaper were told:

"The flag of the diggers, "The Southern Cross," as well as the "Union Jack," which they had to hoist underneath, were captured by the foot police." [2][3]

This flag arrangement was the one featured in an illustrated history resource for students dating from the 1950s. [4]

20th and 21st century investigations into sightings of other Eureka flags

General public interest in the Eureka Stockade is a thing of the relatively recent past, and the Eureka flag used in the 1949 motion picture Eureka Stockade starring Chips Rafferty and associated promotional material was not five stars arrayed on a white cross, rather the free floating stars of the Southern Cross, as per the official Australian national flag; the original specimen was not put on public display until 1973, and was only irrefutably authenticated in 1996 when sketchbooks of Canadian artist Charles Doudiet sold at auction, with the practice of the custodians snipping bits off and giving them to visiting dignitaries still going on within living memory.

Since becoming the custodian of the Eureka flag the Ballarat Fine Art Gallery has searched for the reported second flag in response to public inquiries without success.

In 2013 the Australian Flag Society announced the release of their vexiollogical study of the subject and a worldwide quest and $10,000 reward for information leading to the discovery of the reported second "Eureka Jack" flag. [1] [5]

Erroneous reporting

There is some debate over whether this sole contemporaneous report of an otherwise unaccounted for Union Jack being present is accurate.[5] In his 2012 book Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution, Peter FitzSimons responds:

"In my opinion, this report of the Union Jack being on the same flagpole as the flag of the Southern Cross is not credible. There is no independent corroborating report in any other newspaper, letter, diary or book, and one would have expected Raffaello Carboni, for one, to have mentioned it had that been the case. The paintings of the flag ceremony and battle by Charles Doudiet, who was in Ballarat at the time, depicts no Union Jack. During the trial for High Treason, the flying of the Southern Cross was an enormous issue, yet no mention was ever made of the Union Jack flying beneath."

Constable Hugh King who was in the lead element of the besieging forces, swore in a signed affidavit made at the time that he recalls:

"...three or four hundred yards a heavy fire from the stockade was opened on the troops and me. When the fire was opened on us we received orders to fire. I saw some of the 40th wounded lying on the ground but I cannot say that it was before the fire on both sides. I think some of the men in the stockade should - they had a flag flying in the stockade; it was a white cross of five stars on a blue ground. - flag was afterwards taken from one of the prisoners like a union jack – we fired and advanced on the stockade, when we jumped over, we were ordered to take all we could prisoners..." [6]

Supporters of the two flag theory say the sine quo non of their hypothesis is that second flag may well have been much smaller than the rebel battle flag. Had it been attached to the masthead at eye level, which it may, even with a block and toggle pulley system, which in the event appears to have been jammed, rendering it invisible to the approaching colonial forces except at close range, in the minutes after the first shot was fired, as the miners fought to the end inside the confines of their crude battlement. By the time the famous Eureka flag was lowered and defaced, first hand memories of the accompanying Union Jack, which itself may have been quickly tucked away amid the deadly siege on Bakery Hill, were apparently dissipating only for one single, syndicated report. The lack of notability in any other contemporary accounts may be the result of the Eureka Jack not being flown from the masthead until after the oath was taken, as the endgame drew near, with the Eureka flag being first mentioned by the Ballarat Times a week earlier on 24 November 1854, and hence it was only seen during the final hours of the unrest, after the negative reaction to Eureka commander in chief Peter Lalor's choice of password for the night of 2 December became apparent.

Two flag theories

The first reports of two rebel flags having being captured during battle have been the subject of academic analysis. Some researchers have suggested alternative scenarios which dissent from the conventional wisdom that only the Eureka flag was flown.

Eleventh hour response to divided loyalties and the Vinegar Hill blunder

Two flag theorists have stressed that the contemporaneous report may be credible due to the exacting journalistic standards of the era and that the investigating reporter may have had eyewitness accounts of the two flags having being seized available, and that it was possibly an 11th hour response to the divided loyalties among the heterogeneous rebel force which was in the process of melting away (at one stage 1,500 of 17,280 men in Ballarat were present, with only 150 taking part in the battle), [7] as the rebel password for the night of 2 December - Vinegar Hill - [8] [9] [10] [11] gave an Irish dimension to the struggle, being as it was a reference to the 1804 Castle Hill convict uprising in New South Wales, sometimes known as the sequel to the engagement fought on such a hill in Enniscorthy, County Wexford, during the Irish Rebellion of 1798, causing support for the rebellion to fall away among those who were otherwise disposed to resist the military, as word spread that the question of Irish home rule had become involved. [12]

Phillip Benwell of the Australian Monarchist League has said that few contemporary historians are prepared to admit that the Union Jack was also seen around the diggings at the time as an expression of loyalty to the powers that be; [13] attempts to stir up miners at nearby Creswick Creek are known to have failed when talk turned from abolition of the licence fee to 'separation from Great Britain'. [14] At the mass demonstration held on 29 November, there was disquiet among moderates that the Eureka flag was "the only flag hoisted over the platform". [15] Although he does describe the stars of the Eureka Flag as diamond shaped, the writings of Raffaello Carboni, who was in Ballarat at the time, author of the main, complete eyewitness description and analysis of the causes of the attack on the Eureka Stockade, published a year after the event, make it clear that:

'amongst the foreigners ... there was no democratic feeling, but merely a spirit of resistance to the licence fee"; and he also disputes the accusations "that have branded the miners of Ballarat as disloyal to their QUEEN".'

Eureka historians know that a majority of those present were Irish and it has been discovered that, in the area where the stockade sprung up, there was a large concentration of Irish miners. According to the Ballarat Times: '[at] about eleven o'clock the “Southern Cross” was hoisted, and its maiden appearance was a fascinating object to behold.' Peter Lalor, elected as rebel commander in chief, was himself an Irish immigrant, and parading in front of the peak rebel force, knelt down, took off his hat, and pointed his right hand to the Eureka flag, and swore to the affirmation of his fellow demonstrators: 'We swear by the Southern Cross to stand truly by each other and fight to defend our rights and liberties.' Professor Geoffrey Blainey has advanced the view, that the white cross behind the stars on the Eureka flag 'really [is] an Irish cross rather than being [a] configuration of the Southern Cross'. [5]

Protesters demanded rights of free men in the British Empire

Gregory Blake, military historian and author of Eureka Stockade: A Ferocious and Bloody Battle, concedes two flags may have been flown on the day of the battle, as the miners were claiming to be defending their British rights.

Optical illusion

Vexillographer and former CEO of the Royal Australian Historical Society, John Vaughan, posits that the Union Jack in the adjacent government camp may have created an optical illusion, from a certain perspective common to artists. However this explanation neither explains why the investigating reporter found pressure to fly the Union Jack at the stockade or the source of their information that both flags were by then in the possession of the foot police. It is doubtful that anything other than proximate sightings of two rebel war flags flying could be made before sunrise on the day of the battle itself. [5]

Conspiracy theories

Two flag theorists have conjectured the Eureka Jack may have been willfully destroyed or otherwise allowed to go missing. [5]

Circumstances surrounding omission of Eureka Jack as exhibit in Victorian high treason trials

It is also unlikely the first report was erroneous as John King's battlefield trophy was handed up as an exhibit at the following trial of the 13 miners for high treason. Given the legal position of the Union Jack as a royal flag representing the monarchy used as the defacto flag of the United Kingdom by permission of the reigning sovereign, the fact of its presence may have assisted the defence case against the indictments. According to The Eureka Encyclopedia, Sergeant John McNeil at the time shredded a flag at the Spencer Street Barracks in Melbourne, which was said to be the Eureka flag, but which may well have been a Union Jack.

Provided the Eureka Jack was not the victim of tampering with evidence, it may have been similarly returned to the officer of the peace in question but without being entered into evidence by the prosecution.

Earliest Eureka investigators were communists and radical nationalists

The earliest Eureka investigators were from among the ranks of communists and radical nationalists who may have had ideological motives for allowing the artifact to fade into obscurity or be intentionally done away with.

The Eureka flag was commonly referred to at the time as the Australian flag, and as the Southern Cross, with The Age variously reporting, on 28 November: "The Australian flag shall triumphantly wave in the sunshine of its own blue and peerless sky, over thousands of Australia's adopted sons"; [16] the day after the battle: "They assembled round the Australian flag, which has now a permanent flag-staff"; [17] and during the 1855 Eureka trials, that it was sworn that the Eureka flag was also known as the "digger's flag" and also as "the Southern Cross". [18]

As Vaughan says, the 1854 rebel 'stars and cross' blue and white edition was not the first concept for a continental flag for Australia, nor the first to symbolise Australia with the Southern Cross:

"It is a myth that the Eureka flag flown at the stockade rebellion in 1854 was the first Southern Cross emblem. The acknowledged designer, Henry Ross of Toronto, Canada, would have been influenced by the popularity of already existing starry flags and the 1831 design had its colours reversed to a blue field and white cross and the Union Jack deleted.

"The Eureka flag was lost to general public imagination until after WW2 when, for mainly political reasons it was re-discovered and promoted as a ‘rebel’ symbol." [19]

Similar controversy in Australian vexillology

Two flag theorists point to another similar, seemingly unresolvable controversy over the colour of the Australian flags used at the 1927 opening of provisional parliament house in Canberra, where a lithograph by an unknown artist showing the blue version being flown has emerged, yet the official portrait features the Australian Red Ensign, which it is said was apparently favoured by the commissioned artist for dramatic effect. [5] [20]

Other national treasures and symbols

Two flag theorists have pointed out that Australians have been known to lose track of the cultural wealth with mystery also surrounding the following objects:

- a colour portrait of Peter Lalor in later life wearing 19th century wig and gown as Speaker of the state parliament. Previously on public display at Ballarat Town Hall.

- the first Australian flag which flew over the Royal Exhibition Building in Melbourne, which the custodians believe may have been disposed of due to wear. The Australian flag used at the first formal flag raising ceremony, attended by the inaugural Governor-General, Lord Hopetoun, at Townsville, Queensland, on 16 September 1901, was mentioned on 22 August 1922 as being received by the Royal Australian Historical Society.

- a portrait showing the scene in 1770 as Captain James Cook, hydrographer royal, laid claim to most of the Australian continent on Possession Island, in the name of King George III, has been missing from the Victorian headquarters of the Royal Society in Melbourne since around 1947.

At a government level in Australia there have also been several serious bureaucratic errors made in relation to national symbols legislation and gazettals up until recent times.

The Flags Act 1953 (Cth), which was the first federal statute reserved for Royal Assent by the reigning monarch, originally gave the width of the outer diameter of the Commonwealth Star as being three-eighths of the width of the flag, instead of the true value of three-tenths of the width of the flag, with Table A of the Act requiring further amendment later in 1954.

The Legislative Instruments Act 2003 (Cth) required the proclamations of all the Flags of Australia appointed by the Governor-General to be lodged in a Federal Register. Due to an administrative oversight they were not, and the proclamations were automatically repealed, [21] with His Excellency Major General Michael Jeffery issuing new proclamations backdated from 25 January 2008. [22]

There is also a current instrument still in force declaring Advance Australia Fair to be the national anthem, and green and gold to be the national colours, proclaimed by the Governor-General, Sir Ninian Stephen, on the 19 of April 1984. The PMS colour specifications are transposed with the colour for green (384C) being given as the colour for gold (116C).

See also

- Union Flag

- Eureka Flag

- War flag

- Historical colours, standards and guidons

- List of Australian flags

- List of British flags

- Eureka Rebellion

- Australian Flag Society

- Battle of Vinegar Hill

- Battle of Vinegar Hill, Australia, 1804, also known as the Second Battle of Vinegar Hill, and the Castle Hill convict rebellion

- Victorian gold rush, Australian history (1851 - 1860s)

- Siege of Bakery Hill, 1854, popularly known as the Battle of the Eureka Stockade

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Cowie, Tom (October 22, 2013). "$10,000 reward to track down the 'other' Eureka flag". The Courier.

- ↑ "ergo | Research, resources and essay writing". Slv.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2011-11-29.

- ↑ "By Express. Fatal Collision at Ballaarat.". The Argus (Melbourne, Vic.). 4 December 1854. p. 5.

- ↑ "The Revolt at Eureka", Pictorial Social Studies, Vol 16, pp. 25 – 27.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 Morris, Nigel (3 December 2013). "Ray Wenban and what happened to the Eureka Jack?". 1(1) Flag Breaking News (ISSN 2203-2118). Retrieved 4 December 2013.

- ↑ King, Hugh. "Eureka Stockade:Depositions VPRS 5527/P Unit 2, Item 9". Public Record Office Victoria.

- ↑ Ian MacFarlane, Eureka From the Official Records (Public Records Office, Melbourne, Vic, 1995).

- ↑ Desmond O'Grady. Raffaello! Raffaello!: A Biography of Raffaello Carboni, Hale and Iremonger, Sydney, 1985, pp. 155.

- ↑ H.R. Nicholls. "Reminiscences of the Eureka Stockade", The Centennial Magazine: An Australian Monthly, (May 1890) (available in an annual compilation; Vol. II: August, 1889 to July, 1890), pp. 749.

- ↑ Raffaello Carboni. The Eureka Stockade, Currey O'Neil, Blackburn, Vic., 1980, pp. 90.

- ↑ William Bramwell Withers. The History of Ballarat, From the First Pastoral Settlement to the Present Time, (facsimile of the second edition of 1887), Queensberry Hill Press, Carlton, Vic., 1980, pp. 105.

- ↑ C.H. Currey. The Irish at Eureka, Angus and Robertson, Sydney, 1954, pp. 93.

- ↑ Phillip Benwell, Euerka. Be not misled! The Eureka Stockade has nothing to do with a republic or the Labor Party but everything to do with the Ultimate Supremacy of Law and Justice Under the Crown., (2004) Australian Monarchist League <www.monarchist.org.au/articlesarchive_detail.html?_SKU=12154821304659065&startat=26&index_no=26>.

- ↑ E. Daniel Potts & Annette Potts, American Republicanism and Disturbances on the Victorian Goldfields, Historical Studies, April 1968.

- ↑ Manning Clark, A History of Australia IV, (Melbourne University Press, Cartlon, Vic., reprint 1987) 74.

- ↑ Ballarat Times, cited in The Age, 28 November 1854, p. 5.

- ↑ The Age, 4 December 1854, p. 5.

- ↑ The Age, 24 February 1855, p. 5.

- ↑ Vaughan, John. "Flags under the Southern Cross and the Eureka Myth". Australian National Flag Association.

- ↑ Dr Elizabeth Kwan, Parliament House Puzzle (2003) <http://www.curriculum.edu.au/cce/default.asp?id=9306>.

- ↑ Explanatory Statement accompanying 2008 proclamation, ComLaw database.

- ↑ Legislative Instruments enabled by the Flags Act, ComLaw database.

| ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||