Eulogius Schneider

Eulogius Schneider (baptized as: Johann Georg; October 20, 1756 – April 1, 1794) was a Franciscan monk, professor in Bonn and Dominican in Strasbourg.

Life

Johann Georg Schneider was born as the son of a wine grower and his wife in Wipfeld am Main, a place which belonged to the Prince-Bishopric of Würzburg (a Hochstift, an area ruled by a prince-bishop during the Holy Roman Empire). He had ten siblings.

In Würzburg

His parents intended a religious career for their youngest son. The young Schneider began learning Latin at the nearby Heidenfeld Monastery with the canon Valentin Fahrmann. Fahrmann acquired a place for his 12-year-old student at the Würzburg youth seminary. While at the seminary, Schneider attended the Gymnasium, a secondary school run by the Jesuits, for the next five years.

There was an open conflict between Schneider and his teachers after they discovered Schneider's first attempts at writing and his reading materials, among which were novels and poetry of Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock and Christian Fürchtegott Gellert.

After graduating the Gymnasium, the 17-year-old Schneider decided against training as a theologian at first. Instead, he enrolled at the Julius-Maximilians-Universität in Würzburg in the subjects of philosophy and jurisprudence. As a result, Schneider was "prematurely expelled" from the seminary. Schneider's decision against a religious career at this time was also a decision for a life, which made it possible for him to pursue his literary inclinations. However, these inclinations were not the deciding factor for the termination of his studies, but rather the fact that a love affair of his became known. He had to pay a fine of two Reichstaler because of "premarital sex". Still worse than that, Schneider lost his living as a tutor. The Würzburg religious teachers refused to let their students be instructed by Schneider after his "sin" became known. He had no other choice than to return to the home of his parents in Wipfeld.

Father Eulogius

On the urging of his parents, Schneider decided to begin training in theology after all. At the age of 21, he entered the Franciscan order in Bamberg in April 1777. There, he took the name Eulogius (from the Greek: eu = good, logos = word). Participation in a three-year course of study containing the history of philosophy, metaphysics, logic, morals, history of the Church, and speculative and experimental physics were part of the training as a Franciscan. Rhetoric was supposed to have been the most fun for the young Father Eulogius and his sermons soon acquired a certain popularity.

Following his time in Bamberg, Schneider went to Salzburg to continue and complete his studies. The Salzburg libraries gave him easier access to modern literary and philosophical works, such as the works of the philosophers of the Enlightenment.

After he received his diploma, Eulogius Schneider was ordained as a priest in Salzburg.

After being a lector in Augsburg, he became court chaplain at the court of Württemberg under Karl Eugen, Duke of Württemberg, in 1786, presumably primarily because of his reputation as a gifted orator. Because Schneider supported the ideas of the Enlightenment, there was soon discord with the lord, who threatened to send the court chaplain back to the monastery. However in 1789, his countryman, Thaddäus Trageser, found him a position as a professor for literature and fine arts at the University of Bonn. Schneider's talent as a speaker soon made his lectures very popular. Schneider's most prominent student in Bonn was the young Ludwig van Beethoven. He also taught Friedrich Georg Pape.

Supporter of the French Revolution

In the same year that he started as a professor in Bonn, Eulogius Schneider left the religious order, since his employer did not want to have a monk as a professor, and he became a "secular priest", with papal permission. In the following year, he emerged as an author of books which aroused massive protest among the clerics of the Archbishopric of Cologne, to which the university in Bonn belonged. After Schneider's employer, Archduke Maximilian Franz of Austria first tried to avoid a conflict and refused a petition for release of the Nuncio at Cologne, Bartolomeo Pacca, he finally reacted with a ban on sales. Schneider's public protest lead to his dismissal on June 7, 1791.

As Schneider was an enthusiastic supporter of the French Revolution, his writings included an ode to the Revolution, which concludes with the following verses:

- Gefallen ist des Despotismus Kette,

- Beglücktes Volk! von deiner Hand:

- Des Fürsten Thron ward dir zur Freiheitsstätte

- Das Königreich zum Vaterland.

- Kein Federzug, kein: „Dies ist unser Wille“,

- entscheidet mehr des Bürgers Los.

- Dort lieget sie im Schutte, die Bastille,

- Ein freier Mann ist der Franzos!

A very rough translation:

- The chain of despotism has fallen,

- Happy people! By your hand:

- The princely throne has become a place of freedom for you

- The kingdom has become a fatherland.

- No stroke of the pen, no: "This is our will",

- decides the citizen's lot anymore.

- There it lies in rubble, the Bastille,

- A free man is the Frenchman!

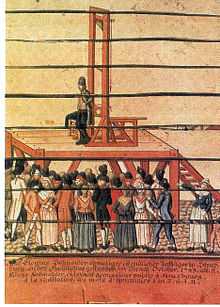

On the scaffold

In 1791, Schneider went to Strasbourg, marked by the Revolution, and took over numerous offices and functions in the following years. He was episcopal vicar and professor at the seminary for priests and preacher at the Strasbourg Cathedral. He finally distanced himself more and more from his clerical office and devoted himself to the revolutionary movement. He became a councillor, the publisher and editor-in-chief of the magazine, "Argos", which was published as of June 1792, and at times the president of the Strasbourg Dominican club. In the course of his increasing radicalization, he was the leader of the surveillance and security committee and the civil commissioner and prosecutor at the Revolutionary Tribunal. In this position, he supported the terror and imposed around thirty death sentences. During this time, he also wrote what is presumably the first German translation of the Marseillaise.

In 1793, Eulogius Schneider married Sara Stamm, the daughter of a Strasbourg wine dealer.

A few hours after his wedding, Schneider was arrested on December 15 on the orders of Saint-Just and Lebas, the commissioner of the National Convention and "Representative on Extraordinary Mission" for Alsace, and he was bound to the guillotine on the Strasbourg "Parade Ground". The reason: Schneider, "former priest and born subject of the (German) Kaiser had driven into Strasbourg with excessive splendor, drawn by six horses, surrounded by guardsmen with bare sabres". Thus, "this Schneider" should be "displayed for show to the people on the scaffold of the guillotine today (December 15, 1793) from 10 o'clock in the morning until 2 o'clock in the afternoon, to atone for the disgrace to the morals of the developing republic." Afterwards, the accused should "be driven from brigade to brigade to Paris to the Committee of the Public Welfare of the National Convention!"

Eulogius Schneider spent his imprisonment in the Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés in Paris. There, he shared a cell with Count Merville, an aristocratic opponent of the Revolution.

On April 1, 1794, Eulogius Schneider was executed by guillotine in Paris.

Schneider's execution must be seen in the context, that the Committee of Public Safety around Maximilien Robespierre had to make concessions to the bourgeoisie, after it had liquidated the girondists and the "right" circles of their Mountain party around Georges Danton, and now also had to take action against the social-revolutionary sans-culottes, of whom Schneider was considered to be an advocate. In addition, Schneider was deemed suspicious in view of his cosmopolitanism, which corresponded to the political positions of the gironde in this respect.

Opinions on Eulogius Schneider

Saint-Just and Lebas to Robespierre, December 14, 1793:

We are delivering the public prosecutor of the Strasbourg Revolutionary Tribunal to the Committee of Public Safety. He is a former priest, born a subject of the Kaiser. Before he was taken away from Strasbourg, he was pilloried on the scaffold of the guillotine. This punishment, which he incurred because of his brazen conduct, was also urgently necessary to exert pressure on foreign parts. We do not believe in the cosmopolitan charlatan and we only trust ourselves.

We embrace You with all our heart.

Marianne Schneider, Eulogius Schneider's sister, to Saint-Just:

Strasburg, the 28th of Frimaire II (December 18, 1793)

Citizen! Representative!

The deeply aggrieved sister of the unfortunate Schneider stands before you. You are the representative of a just, noble people. If my brother is innocent, defend him, that is your duty. If he has fallen into mistakes, support him; do not let him sink, since you must know that his intentions were always good and honest. If he is a criminal, oh, allow me to cry. I have done my duty as a sister, do yours as a republican. I can do nothing but cry, you can act. Long live the Republic! Long live the Convention!

Paul Scheffer, pharmacist in Strasbourg:

Since this German priest came running, this monk without a cowl and former professor in Bonn came to Strasbourg in June of 1792, he has only sown discord and done damage among the good, industrious and god-fearing inhabitants of this area. Thanks be to the commissioners of the Convention, that you have finally freed us from this monster and paid agent from abroad!

Moshua Salomon, Jewish tradesman:

The citizen Schneider was a true patriot and cosmopolitan, a man of principles. If he had not held his hand protectively above us and defended our newly-acquired civil rights again and again, I and my Jewish co-citizens would have fared quite badly in the time of terror. Not a few of the sworn enemies of Judaea, of whom there were all too many in Alsace, wanted to commend us to the "promenade à la guillotine"; the very least would have been our expulsion and deportation, against which the citizen Schneider raised his voice again and again.

(Source: Michael Schneider, see "Literature")

Selected works

All works are in German, except where noted.

- De philosophiae in sacro tribunali usu commentatio, 1786 (in Latin);

- Rede über die christliche Toleranz auf Katharinentag, 1785, held in Augsburg, 1786;

- Des heiligen Chrysostomus Kirchenvaters und Erzbischoffs zu Konstantinopel Reden über das Evangelium des heiligen Matthei. From the Greek (according to the newest Paris edition) translated and with notes by Johann Michael Feder and E. Sch., 2 vols., 4 dept., 1786–88;

- Freymüthige Gedanken über den Werth und die Brauchbarkeit der Chrysostomischen Erklärungsreden über das Neue Testament und deren Uebersetzung, 1787;

- Oden eines Franziscaner Mönchs auf den Rettertod Leopolds von Braunschweig, 1787;

- Ode an die verehrungswürdigen Glieder der Lesegesellschaft zu Bonn, als das Bildniß unsers erhabenen Kurfürsten im Versammlungssaale feyerlich aufgestellt wurde, 1789;

- Rede über den gegenwärtigen Zustand, und die Hindernisse der schönen Litteratur im katholischen Deutschlande, 1789;

- Elegie an den sterbenden Kaiser Joseph II., 1790;

- Die ersten Grundsätze der schönen Künste überhaupt, und der schönen Schreibart insbesondere, 1790;

- Gedichte. With a portrait of the author, 1790 (51812) [Reprint 1985];

- Katechetischer Unterricht in den allgemeinsten Grundsätzen des praktischen Christenthums, 1790;

- Patriotische Rede über Joseph II. in höchster Gegenwart Sr. kurfürstl. Durchl. von Cöln, held before the literary society of Bonn on March 19, 1790, 1790;

- Predigt über den Zweck Jesu bey der Stiftung seiner Religion, held in the court chapel of Bonn on December 20, 1789, 1790;

- Trauerrede auf Joseph II. held before the high Imperial Supreme Court of Wetzlar, 1790;

- Das Bild des guten Volkslehrers, entworfen in einer Predigt über Matth. VII, 15, am 17ten Sonntage nach Pfingsten, 1791;

- De novo rerum theologicarum in Francorum imperio ordine commentatio, 1791 (in Latin);

- Die Quellen des Undankes gegen Gott, den Stifter und Gründer unserer weisen Staatsverfassung, dargestellt in einer Predigt über Luk. XVII, 17, am 13ten Sonntage nach Pfingsten, 1791;

- Die Übereinstimmung des Evangeliums mit der neuen Staats-Verfassung der Franken. A speech when swearing the solemn civic oath, 1791;

- Rede über die Priesterehe, of the Society of Friends of the Constitution on October 11, 1791, read in the session of Strasbourg. Translated from French and with notes, 1791;

- Argos, oder der Mann mit hundert Augen, 4 Vols. [4th Vol. publ. by Friedrich Butenschön and Johann Jakob Kämmerer] 1792-1794 [Reprint 1976];

- Auf die Erklärung der National-Versammlung Frankreichs an die Völker Europa's und die ganze Menschheit, in Rücksicht des bevorstehenden Krieges vom 29. December 1791, 1792;

- Auf Kaiser Leopolds II. Tod, 1792;

- Discours sur l'éducation des femmes, held before the Society of Friends of the Constitution meeting in Strasbourg, 1792 (in French);

- Gedächtnisrede auf Mirabeau vor der Gesellschaft der Constitutionsfreunde, 1792;

- Jesus der Volksfreund, 1792;

- Politisches Glaubensbekenntnis, presented to the Society of Friends of the Constitution, 1792;

- Von einem deutschen Bauern am Rhein, 1792;

- Ernste Betrachtungen über sein trauriges Schicksal, nebst flüchtigem Rückblick auf seinen geführten Lebenswandel kurz vor seiner Hinrichtung von ihm selbst geschrieben, 1794;

- Der Guckkasten, a funny poem in three songs. From his posthumous papers, 1795;

References

- Michael Schneider: Der Traum der Vernunft - Roman eines deutschen Jakobiners, 2002, ISBN 3-462-03160-0 (in German)

- Claude Betzinger, Vie et mort d’Euloge Schneider, ci-devant franciscain. Des lumières à la terreur, 1756-1794. Strasbourg 1997 (not consulted, in French)

- Walter Grab, Eulogius Schneider - ein Weltbürger zwischen Mönchszelle und Guillotine in: "Ein Volk muss seine Freiheit selbst erobern - Zur Geschichte der deutschen Jakobiner", Frankfurt, Olten, Vienna 1984, p. 109 ff. ISBN 3-7632-2965-5 (in German)

External links

- Eulogius Schneider in the German National Library catalogue

- Silvia Wimmer (1995). "Schneider, Eulogius (Taufname: Johann Georg)". In Bautz, Traugott. Biographisch-Bibliographisches Kirchenlexikon (BBKL) (in German) 9. Herzberg: Bautz. cols. 547–551. ISBN 3-88309-058-1.

- Short biography with newer bibliography

- Franz Xaver von Wegele (1891), "Schneider, Eulogius", Allgemeine Deutsche Biographie (ADB) (in German) 32, Leipzig: Duncker & Humblot, pp. 103–108

- Hamel: Histoire de Saint-Just PDF

- This article incorporates information from this version of the equivalent article on the German Wikipedia.

|