Euhelopus

| Euhelopus Temporal range: Early Cretaceous | |

|---|---|

| |

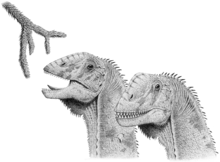

| Restorations of the skull | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Sauropsida |

| Superorder: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Infraorder: | †Sauropoda |

| (unranked): | †Titanosauriformes |

| Family: | †Euhelopodidae |

| Genus: | †Euhelopus |

| Binomial name | |

| Euhelopus zdanskyi Wiman, 1929 | |

Euhelopus is a genus of titanosauriform sauropod dinosaur that lived between 129 and 113 million years ago during the Early Cretaceous[1] in what is now Shandong Province in China. It was a large bipedal herbivore, it weighed approximately 15-20 tons and attained an adult length of 15 m (49 ft)[2] Unlike most other sauropods, Euhelopus had longer forelegs than hind legs. This discovery was paleontologically significant because it represented the first dinosaur described from China: seen in 1913, rediscovered in 1922, and excavated in 1923.[3] Unlike most sauropod specimens, it has a relatively complete skull.[4]

Discovery and naming

It was originally named Helopus, meaning "Marsh Foot" by Carl Wiman in 1929, but this name already belonged to a bird. It was renamed Euhelopus (Good marsh-foot) in 1956 by Romer. There is a plant genus (a grass) with the same generic name. However, a genus in one biological kingdom may have a name that is used as a genus name in another kingdom, so Euhelopus was allowed.

Description

Specimens PMU 24705 (formerly PMU R233) and PMU 24706 (formerly PMU R234) form the descriptive basis for the type species, Euhelopus zdanskyi.[4]

Specimen PMU 24706 comprises nine articulated dorsal vertebrae and the sacrum, two dorsal ribs, a nearly complete pelvis, and a right hindlimb lacking metatarsal V and several pedal phalanges.[2]

Specimen PMU 24705 comprises these bones: the rostral part of the left nasal; a partial right jugal; the tapered jugal process of the postorbital, partially excavated; the dorsal process of the right quadratojugla; and the fragmented left pterygoid. Another fragment might be the right splenial, but it is too fragile to be removed from its matrix.[4]

Classification

Wilson and Upchurch (2009) noted that cladistic assessments suggest that Euhelopus belonged to a clade of sauropods, the Euhelopodidae, that originated during an interval of geographic isolation and was endemic to this geographical range in China. It is not clear if the Euhelopodidae are monophyletic.[1] Euhelopus demonstrates phylogenetic affinity to the taxon Titanosauria. Traditional claims that Euhelopus, Omeisaurus, Mamenchisaurus and Shunosaurus form the monophyletic family “Euhelopodidae” are not supported by new phylogenetic analysis.[5]

The cladogram below follows José L. Carballido, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, Diego Pol and Leonardo Salgado (2011).[5]

| Camarasauromorpha |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

Distinguishing anatomical features

A diagnosis is a statement of the anatomical features of an organism (or group) that collectively distinguish it from all other organisms. Some, but not all, of the features in a diagnosis are also autapomorphies. An autapomorphy is a distinctive anatomical feature that is unique to an organism or group.

According to Wilson and Upchurch (2009), Euhelopus can be distinguished based on these characteristics:[1]

- The postaxial cervical vertebrae have variably developed epipophyses and more subtle “pre‐epipopophyses” below the prezygapophyses.

- The cervical neural arches have an epipophyseal‐prezygapophyseal lamina separating the two pneumatocoels.

- The anterior cervical vertebrae have three costal spurs on the tuberculum and capitulum.

- The middle presacral neural spines are divided, and in anterior dorsal vertebrae bear a median tubercle that is at least as large as the metapophyses.

- The middle and posterior dorsal parapophyseal and diapophyseal laminae are arranged in a “K” configuration.

- The presacral pneumaticity extends into the ilium.

Paleoecology

Provenance and occurrence

The type material for Euhelopus was excavated at the Mengyin Formation in Shandong (Shantung) Province, China. The specimen was collected by Otto Zdansky in 1923, in green/yellow sandstone and green/yellow siltstone that were deposited during the Barremian or Aptian stages of the Cretaceous period, about 129 to 113 million years ago. This specimen is housed in the collection of the Paleontological Museum of Uppsala University, in Uppsala, Sweden. The original discovery was by a Catholic priest, Father Metrens, in 1913. The site was rediscovered 1922 by Andersson and T'an.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Wilson, Jeffrey A.; and Upchurch, Paul (2009). "Redescription and reassessment of the phylogenetic affinities of Euhelopus zdanskyi (Dinosauria:Sauropoda) from the Early Cretaceous of China". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 7 (2): 199–239. doi:10.1017/S1477201908002691.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 "Euhelopus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 70. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 H. C. T'an. 1923. New research on the Mesozoic and early Tertiary geology in Shantung. Geological Survey of China Bulletin 5:95-135

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Poropat, Stephen F.; Kear, Benjamin P. (2013-11-21). Photographic Atlas and Three-Dimensional Reconstruction of the Holotype Skull of Euhelopus zdanskyi with Description of Additional Cranial Elements. PLOS One. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0079932. Retrieved 2013-12-07.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 José L. Carballido, Oliver W. M. Rauhut, Diego Pol and Leonardo Salgado (2011). "Osteology and phylogenetic relationships of Tehuelchesaurus benitezii (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Upper Jurassic of Patagonia". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 163 (2): 605–662. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2011.00723.x.

- Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB (2005). "Sauropodomorpha: the big, the bizarre and the majestic". In Fastovsky DE, Weishampel DB. The Evolution and Extinction of the Dinosaurs (2nd Edition). Cambridge University Press. pp. 229–264. ISBN 0-521-81172-4.