Esophagus

| Esophagus | |

|---|---|

| |

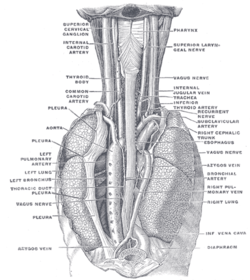

| The esophagus relations to pharynx and mouth | |

| |

| Digestive organs (esophagus is #1) | |

| Latin | Esophagus |

| Gray's | subject #245 1144 |

| System | Part of the Digestive system |

| Artery | Esophageal arteries |

| Vein | Esophageal veins |

| Nerve | Celiac ganglia, vagus[1] |

| Precursor | Foregut |

| MeSH | Esophagus |

| Dorlands/Elsevier | Esophagus |

The esophagus (oesophagus, commonly known as the gullet) is an organ in vertebrates which consists of a muscular tube through which food passes from the pharynx to the stomach. The word esophagus is derived from the Latin œsophagus, which derives from the Greek word oisophagos, lit. "entrance for eating."

Structure

In humans the esophagus is continuous with the laryngeal part of the pharynx at the level of the C6 vertebra. The esophagus passes through posterior mediastinum in the thorax and enters abdomen through a hole in the diaphragm at the level of the tenth thoracic vertebrae (T10). It is usually about 25cm, but extreme variations have been recorded ranging 10–50 cm long depending on individual height. It is divided into cervical, thoracic and abdominal parts. Due to the inferior pharyngeal constrictor muscle, the entry to the esophagus opens only when swallowing or vomiting.

In animals, food is ingested through the mouth. During swallowing, food passes from the mouth through the pharynx into the esophagus. The epiglottis folds down to a more horizontal position so as to prevent food from going into the trachea, instead directing it to the esophagus. Once in the esophagus, the bolus travels down to the stomach via rhythmic contraction and relaxation of muscles known as peristalsis.

Esophageal sphincters

At rest, the esophagus is closed at both ends by the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) at the top, and the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) at the bottom.

The junction between the esophagus and the stomach (the gastroesophageal junction or GE junction) is controlled by the lower esophageal sphincter (LES), which remains constricted at all times other than during swallowing and vomiting to prevent the contents of the stomach from entering the esophagus. As the esophagus does not have the same protection from acid as the stomach, any failure of the LES can lead to heartburn.

Constrictions

Normally, the esophagus has three anatomic constrictions at the following levels:

- At the esophageal inlet, where the pharynx joins the esophagus, behind the cricoid cartilage (14–16 cm from the incisor teeth).

- Where its anterior surface is crossed by the aortic arch and the left bronchus (25–27 cm from the incisor teeth).

- Where it pierces the diaphragm (36–38 cm from the incisor teeth).

The distances from the incisor teeth are important as is useful for diagnostic endoscopic procedures.

Histology

The oesophagus has a mucosa consisting of a stratified squamous epithelium without keratin, a smooth lamina propria, and a muscularis mucosae of smooth muscle. The submucosa contains the mucous secreting glands (esophageal glands), and connective structures termed papillae. The muscularis externa has a unique composition, varying over the length of the oesophagus. The upper third of the muscularis is striated muscle, the middle third both smooth muscle and striated muscle, and the lower third predominantly smooth muscles. The oesophagus also has an adventitia.[2]

The epithelium of the oesphagus has a relatively rapid turnover, and serves a protective function due to the high volume transit of food, saliva and mucus.

Function

Peristalsis

In the esophagus, as in much of the gastrointestinal tract, smooth muscles contract in sequence to produce a peristaltic wave which forces a ball of food (called a bolus) down and through the LES into the stomach.

Clinical relevance

History

In other animals

In most fish, the esophagus is extremely short, primarily due to the length of the pharynx (which is associated with the gills). However, some fish, including lampreys, chimaeras, and lungfish, have no true stomach, so that the esophagus effectively runs from the pharynx directly to the intestine, and is therefore somewhat longer.[3]

In tetrapods, the pharynx is much shorter, and the esophagus correspondingly longer, than in fish. In amphibians, sharks and rays, the esophageal epithelium is ciliated, helping to wash food along, in addition to the action of muscular peristalsis. In the majority of vertebrates, the esophagus is simply a connecting tube, but in birds, it is extended towards the lower end to form a crop for storing food before it enters the true stomach.[3]

A structure with the same name is often found in invertebrates, including molluscs and arthropods, connecting the oral cavity with the stomach.

See also

- Esophageal disease

- Esophageal sphincter

Additional images

-

Esophagus

-

H&E stain of biopsy of normal esophagus showing the stratified squamous cell epithelium

-

Layers of the esophagus.

-

Mid-esophageal mass

-

Stomach

-

Accessory digestive system.

-

Organs of the digestive tract.

-

Esophagus

-

Section of the neck at about the level of the sixth cervical vertebra.

-

Transverse section of thorax, showing relations of pulmonary artery.

-

Sagittal section of nose mouth, pharynx, and larynx.

-

The position and relation of the esophagus in the cervical region and in the posterior mediastinum. Seen from behind. |

-

Section of the human esophagus. Moderately magnified.

-

Microscopic shot of a cross section of human gastroesophageal junction wall.

-

Esophagus

-

Ultrasound image of the fetal esophagus at 19 weeks of pregnancy.

References

External links

| Look up esophagus in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Virtual Slidebox at Univ. Iowa Slide 449

- Esophagus Foreign Body MedPix Radiology Teaching File

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||