Erdős–Straus conjecture

In number theory, the Erdős–Straus conjecture states that for all integers n ≥ 2, the rational number 4/n can be expressed as the sum of three unit fractions. Paul Erdős and Ernst G. Straus formulated the conjecture in 1948.[1] It is one of many conjectures by Erdős.

More formally, the conjecture states that, for every integer n ≥ 2, there exist positive integers x, y, and z such that

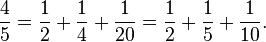

These unit fractions form an Egyptian fraction representation of the number 4/n. For instance, for n = 5, there are two solutions:

The restriction that x, y, and z be positive is essential to the difficulty of the problem, for if negative values were allowed the problem could be solved trivially. Also, if n is a composite number, n = pq, then an expansion for 4/n could be found immediately from an expansion for 4/p or 4/q. Therefore, if a counterexample to the Erdős–Straus conjecture exists, the smallest n forming a counterexample would have to be a prime number, and it can be further restricted to one of six arithmetic progressions modulo 840.[2] Computer searches have verified the truth of the conjecture up to n ≤ 1014,[3] but proving it for all n remains an open problem.

Background

The search for expansions of rational numbers as sums of unit fractions dates to the mathematics of ancient Egypt, in which Egyptian fraction expansions of this type were used as a notation for recording fractional quantities. The Egyptians produced tables such as the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus 2/n table of expansions of fractions of the form 2/n, most of which use either two or three terms.

The greedy algorithm for Egyptian fractions, first described in 1202 by Fibonacci in his book Liber Abaci, finds an expansion in which each successive term is the largest unit fraction that is no larger than the remaining number to be represented. For fractions of the form 2/n or 3/n, the greedy algorithm uses at most two or three terms respectively. More generally, it can be shown that a number of the form 3/n has a two-term expansion if and only if n has a factor congruent to 2 modulo 3, and requires three terms in any expansion otherwise.[4]

Thus, for the numerators 2 and 3, the question of how many terms are needed in an Egyptian fraction is completely settled, and fractions of the form 4/n are the first case in which the worst-case length of an expansion remains unknown. The greedy algorithm produces expansions of length two, three, or four depending on the value of n modulo 4; when n is congruent to 1 modulo 4, the greedy algorithm produces four-term expansions. Therefore, the worst-case length of an Egyptian fraction of 4/n must be either three or four. The Erdős–Straus conjecture states that, in this case, as in the case for the numerator 3, the maximum number of terms in an expansion is three.

Modular identities

Multiplying both sides of the equation 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z by nxyz leads to an equivalent form 4xyz = n(xy + xz + yz) for the problem.[5] As a polynomial equation with integer variables, this is an example of a Diophantine equation. The Hasse principle for Diophantine equations asserts that an integer solution of a Diophantine equation should be formed by combining solutions obtained modulo each possible prime number. On the face of it this principle makes little sense for the Erdős–Straus conjecture, as the equation 4xyz = n(xy + xz + yz) is easily solvable modulo any prime. Nevertheless, modular identities have proven a very important tool in the study of the conjecture.

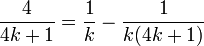

For values of n satisfying certain congruence relations, one can find an expansion for 4/n automatically as an instance of a polynomial identity. For instance, whenever n ≡ 2 (mod 3), 4/n has the expansion

Here each of the three denominators n, (n − 2)/3 + 1, and n((n − 2)/3 + 1) is a polynomial of n, and each is an integer whenever n is 2 (mod 3). The greedy algorithm for Egyptian fractions finds a solution in three or fewer terms whenever n is not 1 or 17 (mod 24), and the n ≡ 17 (mod 24) case is covered by the 2 (mod 3) relation, so the only values of n for which these two methods do not find expansions in three or fewer terms are those congruent to 1 (mod 24).

If it were possible to find solutions such as the ones above for enough different moduli, forming a complete covering system of congruences, the problem would be solved. However, as Mordell (1967) showed, a polynomial identity that provides a solution for values of n congruent to r mod p can exist only when r is not a quadratic residue modulo p. For instance, 2 is a not a quadratic residue modulo 3, so the existence of an identity for values of n that are congruent to 2 modulo 3 does not contradict Mordell's result, but 1 is a quadratic residue modulo 3 so the result proves that there can be no similar identity for values of n that are congruent to 1 modulo 3.

Mordell lists polynomial identities that provide three-term Egyptian fractions for 4/n whenever n is 2 mod 3 (above), 3 mod 4, 5 mod 8, 2 or 3 mod 5, or 3, 5, or 6 mod 7. These identies cover all the numbers that are not quadratic residues for those bases. However, for larger bases, not all nonresidues are known to be covered by relations of this type. From Mordell's identities one can conclude that there exists a solution for all n except possibly those that are 1, 121, 169, 289, 361, or 529 modulo 840. 1009 is the smallest prime number that is not covered by this system of congruences. By combining larger classes of modular identities, Webb and others showed that the fraction of n in the interval [1,N] that can be counterexamples to the conjecture tends to zero in the limit as N goes to infinity.[6]

Despite Mordell's result limiting the form these congruence identities can take, there is still some hope of using modular identities to prove the Erdős–Straus conjecture. No prime number can be a square, so by the Hasse–Minkowski theorem, whenever p is prime, there exists a larger prime q such that p is not a quadratic residue modulo q. One possible approach to proving the conjecture would be to find for each prime p a larger prime q and a congruence solving the 4/n problem for n ≡ p (mod q); if this could be done, no prime p could be a counterexample to the conjecture and the conjecture would be true.

Computational verification

Various authors have performed brute-force searches for counterexamples to the conjecture; these searches can be greatly sped up by considering only prime numbers that are not covered by known congruence relations.[7] Searches of this type by Allan Swett confirmed that the conjecture is true for all n up to 1014.[3]

The number of solutions

The number of distinct solutions to the 4/n problem, as a function of n, has also been found by computer searches for small n and appears to grow somewhat irregularly with n. Starting with n = 3, the numbers of distinct solutions with distinct denominators are

Even for larger n there can be relatively few solutions; for instance there are only seven distinct solutions for n = 73.

Elsholtz & Tao (2011) have shown that the average number of solutions to the 4/n problem (averaged over the prime numbers up to n) is upper bounded polylogarithmically in n. For some other Diophantine problems, it is possible to prove that a solution always exists by proving asymptotic lower bounds on the number of solutions, but proofs of this type exist primarily for problems in which the number of solutions grows polynomially, so Elsholtz and Tao's result makes a solution of this type less likely.[8] The proof of Elsholtz and Tao's bound on the number of solutions involves the Bombieri–Vinogradov theorem, the Brun–Titchmarsh theorem, and a system of modular identities, valid when n is congruent to −c or −1/c modulo 4ab, where a and b are any two coprime positive integers and c is any odd factor of a + b. For instance, setting a = b = 1 gives one of Mordell's identities, valid when n is 3 (mod 4).

Negative-number solutions

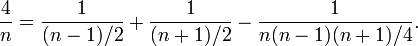

The restriction that x, y, and z be positive is essential to the difficulty of the problem, for if negative values were allowed the problem could be solved trivially via one of the two identities

and

Alternatively, for any odd n, a three-term solution with one negative term is possible:[9]

Generalizations

A generalized version of the conjecture states that, for any positive k there exists a number N such that, for all n ≥ N, there exists a solution in positive integers to k/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z. The version of this conjecture for k = 5 was made by Wacław Sierpiński, and the full conjecture is due to Andrzej Schinzel.[10]

Even if the generalized conjecture is false for any fixed value of k, then the number of fractions k/n with n in the range from 1 to N that do not have three-term expansions must grow only sublinearly as a function of N.[6] In particular, if the Erdős–Straus conjecture itself (the case k = 4) is false, then the number of counterexamples grows only sublinearly. Even more strongly, for any fixed k, only a sublinear number of values of n need more than two terms in their Egyptian fraction expansions.[11] The generalized version of the conjecture is equivalent to the statement that the number of unexpandable fractions is not just sublinear but bounded.

When n is an odd number, by analogy to the problem of odd greedy expansions for Egyptian fractions, one may ask for solutions to k/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z in which x, y, and z are distinct positive odd numbers. Solutions to this equation are known to always exist for the case that k = 3.[12]

Notes

- ↑ See, e.g., Elsholtz (2001). Note however that the earliest published reference to it appears to be Erdős (1950).

- ↑ Mordell (1967).

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Swett, Allan, The Erdos-Straus Conjecture, retrieved 2006-09-09.

- ↑ Eppstein (1995).

- ↑ See e.g. Sander (1994) for a simpler Diophantine formulation using more specific assumptions about which of x, y, and z are divisible by n.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Webb (1970); Vaughan (1970); Li (1981); Yang (1982); Ahmadi & Bleicher (1998); Elsholtz (2001).

- ↑ Obláth (1950); Rosati (1954); Kiss (1959); Bernstein (1962); Yamamoto (1965); Terzi (1971); Jollensten (1976); Kotsireas (1999).

- ↑ On the number of solutions to 4/p = 1/n_1 + 1/n_2 + 1/n_3, Terence Tao, "What's new", July 7, 2011.

- ↑ Jaroma (2004).

- ↑ Sierpiński (1956); Vaughan (1970).

- ↑ Hofmeister & Stoll (1985).

- ↑ Schinzel (1956); Suryanarayana & Rao (1965); Hagedorn (2000).

References

- Ahmadi, M. H.; Bleicher, M. N. (1998), "On the conjectures of Erdős and Straus, and Sierpiński on Egyptian fractions", International Journal of Mathematical and Statistical Sciences 7 (2): 169–185, MR 1666363.

- Bernstein, Leon (1962), "Zur Lösung der diophantischen Gleichung m/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z, insbesondere im Fall m = 4", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik (in German) 211: 1–10, MR 0142508.

- Elsholtz, Christian (2001), "Sums of k unit fractions", Transactions of the American Mathematical Society 353 (8): 3209–3227, doi:10.1090/S0002-9947-01-02782-9, MR 1828604.

- Elsholtz, Christian; Tao, Terence (2011), Counting the number of solutions to the Erdős–Straus equation on unit fractions, arXiv:1107.1010.

- Eppstein, David (1995), Small numerators, "Ten algorithms for Egyptian fractions", Mathematica in Education and Research 4 (2): 5–15

- Erdős, Paul (1950), "Az 1/x1 + 1/x2 + ... + 1/xn = a/b egyenlet egész számú megoldásairól (On a Diophantine Equation)", Mat. Lapok. (in Hungarian) 1: 192–210, MR 0043117.

- Guy, Richard K. (2004), Unsolved Problems in Number Theory (3rd ed.), Springer Verlag, pp. D11, ISBN 0-387-20860-7.

- Hagedorn, Thomas R. (2000), "A proof of a conjecture on Egyptian fractions", American Mathematical Monthly (Mathematical Association of America) 107 (1): 62–63, doi:10.2307/2589381, JSTOR 2589381, MR 1745572.

- Hofmeister, Gerd; Stoll, Peter (1985), "Note on Egyptian fractions", Journal für die Reine und Angewandte Mathematik 362: 141–145, MR 809971.

- Jaroma, John H. (2004), "On expanding 4/n into three Egyptian fractions", Crux Mathematicorum 30 (1): 36–37.

- Jollensten, Ralph W. (1976), "A note on the Egyptian problem", Proceedings of the Seventh Southeastern Conference on Combinatorics, Graph Theory, and Computing (Louisiana State Univ., Baton Rouge, La., 1976), Congressus Numerantium XVII, Winnipeg, Man.: Utilitas Math., pp. 351–364, MR 0429735.

- Kiss, Ernest (1959), "Quelques remarques sur une équation diophantienne", Acad. R. P. Romîne Fil. Cluj Stud. Cerc. Mat. (in Romanian) 10: 59–62, MR 0125069.

- Kotsireas, Ilias (1999), "The Erdős-Straus conjecture on Egyptian fractions", Paul Erdős and his mathematics (Budapest, 1999), Budapest: János Bolyai Math. Soc., pp. 140–144, MR 1901903.

- Li, De Lang (1981), "Equation 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z", Journal of Number Theory 13 (4): 485–494, doi:10.1016/0022-314X(81)90039-1, MR 0642923.

- Mordell, Louis J. (1967), Diophantine Equations, Academic Press, pp. 287–290.

- Obláth, Richard (1950), "Sur l'équation diophantienne 4/n = 1/x1 + 1/x2 + 1/x3", Mathesis (in French) 59: 308–316, MR 0038999.

- Rosati, Luigi Antonio (1954), "Sull'equazione diofantea 4/n = 1/x1 + 1/x2 + 1/x3", Boll. Un. Mat. Ital. (3) (in Italian) 9: 59–63, MR 0060526.

- Sander, J. W. (1994), "On 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z and Iwaniec' half-dimensional sieve", Journal of Number Theory 46 (2): 123–136, doi:10.1006/jnth.1994.1008, MR 1269248.

- Schinzel, André (1956), "Sur quelques propriétés des nombres 3/n et 4/n, où n est un nombre impair", Mathesis (in French) 65: 219–222, MR 0080683.

- Sierpiński, Wacław (1956), "Sur les décompositions de nombres rationnels en fractions primaires", Mathesis (in French) 65: 16–32, MR 0078385.

- Suryanarayana, D.; Rao, N. Venkateswara (1965), "On a paper of André Schinzel", J. Indian Math. Soc. (N.S.) 29: 165–167, MR 0202659.

- Terzi, D. G. (1971), "On a conjecture by Erdős-Straus", Nordisk Tidskr. Informationsbehandling (BIT) 11 (2): 212–216, doi:10.1007/BF01934370, MR 0297703.

- Vaughan, R. C. (1970), "On a problem of Erdős, Straus and Schinzel", Mathematika 17 (02): 193–198, doi:10.1112/S0025579300002886, MR 0289409

- Webb, William A. (1970), "On 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society (American Mathematical Society) 25 (3): 578–584, doi:10.2307/2036647, JSTOR 2036647, MR 0256984.

- Yamamoto, Koichi (1965), "On the Diophantine equation 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z", Memoirs of the Faculty of Science. Kyushu University. Series A. Mathematics 19: 37–47, doi:10.2206/kyushumfs.19.37, MR 0177945.

- Yang, Xun Qian (1982), "A note on 4/n = 1/x + 1/y + 1/z", Proceedings of the American Mathematical Society 85 (4): 496–498, doi:10.2307/2044050, JSTOR 2044050, MR 660589.

External links

- Weisstein, Eric W., "Erdos-Straus Conjecture", MathWorld.

- Counting the number of solutions to the Erdös-Straus equation on unit fractions, Terence Tao, July 31, 2011.