Equidiagonal quadrilateral

In Euclidean geometry, an equidiagonal quadrilateral is a convex quadrilateral whose two diagonals have equal length. Equidiagonal quadrilaterals were important in ancient Indian mathematics, where quadrilaterals were classified first according to whether they were equidiagonal and then into more specialized types.[1]

Special cases

Examples of equidiagonal quadrilaterals include the isosceles trapezoids, rectangles and squares.

Among all quadrilaterals, the shape that has the greatest ratio of its perimeter to its diameter is an equidiagonal kite with angles π/3, 5π/12, 5π/6, and 5π/12.[2]

Characterizations

A convex quadrilateral is equidiagonal if and only if its Varignon parallelogram, the parallelogram formed by the midpoints of its sides, is a rhombus. An equivalent condition is that the bimedians of the quadrilateral are perpendicular.[3]

Area

The area K of an equidiagonal quadrilateral can easily be calculated if the length of the bimedians m and n are known. Then[4]:p.19

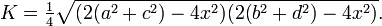

This is a direct consequence of the fact that the area of a convex quadrilateral is twice the area of its Varignon parallelogram and that the diagonals in this parallelogram are the bimedians of the quadrilateral. Using the formulas for the lengths of the bimedians, the area can also be expressed in terms of the sides a, b, c, d of the equidiagonal quadrilateral and the distance x between the midpoints of the diagonals as[4]:p.19

Other area formulas may be obtained from setting p = q in the formulas for the area of a convex quadrilateral.

Relation to other types of quadrilaterals

A parallelogram is equidiagonal if and only if it is a rectangle,[5] and a trapezoid is equidiagonal if and only if it is an isosceles trapezoid.

There is a duality between equidiagonal quadrilaterals and orthodiagonal quadrilaterals: a quadrilateral is equidiagonal if and only if its Varignon parallelogram is orthodiagonal (a rhombus), and the quadrilateral is orthodiagonal if and only if its Varignon parallelogram is equidiagonal (a rectangle).[3] Equivalently, a quadrilateral has equal diagonals if and only if it has perpendicular bimedians, and it has perpendicular diagonals if and only if it has equal bimedians.[6] Silvester (2006) gives further connections between equidiagonal and orthodiagonal quadrilaterals, via a generalization of van Aubel's theorem.[7]

Quadrilaterals that are both orthodiagonal and equidiagonal, and in which the diagonals are at least as long as all of the quadrilateral's sides, have the maximum area for their diameter among all quadrilaterals, solving the n = 4 case of the biggest little polygon problem. The square is one such quadrilateral, but there are infinitely many others.

References

- ↑ Colebrooke, Henry-Thomas (1817), Algebra, with arithmetic and mensuration, from the Sanscrit of Brahmegupta and Bhascara, John Murray, p. 58.

- ↑ Ball, D.G. (1973), "A generalisation of π", Mathematical Gazette 57 (402): 298–303, doi:10.2307/3616052; Griffiths, David; Culpin, David (1975), "Pi-optimal polygons", Mathematical Gazette 59 (409): 165–175, doi:10.2307/3617699.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 de Villiers, Michael (2009), Some Adventures in Euclidean Geometry, Dynamic Mathematics Learning, p. 58, ISBN 9780557102952.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Josefsson, Martin, "Five Proofs of an Area Characterization of Rectangles", Forum Geometricorum 13 (2013) 17–21.

- ↑ Gerdes, Paulus (1988), "On culture, geometrical thinking and mathematics education", Educational Studies in Mathematics 19 (2): 137–162, JSTOR 3482571.

- ↑ Josefsson, Martin (2012), "Characterizations of Orthodiagonal Quadrilaterals", Forum Geometricorum 12: 13–25. See in particular Theorem 7 on p. 19.

- ↑ Silvester, John R. (2006), "Extensions of a theorem of Van Aubel", The Mathematical Gazette 90 (517): 2–12, JSTOR 3621406.