Equations of motion

| Classical mechanics |

|---|

|

Fundamental concepts |

|

Core topics |

In mathematical physics, equations of motion are equations that describe the behaviour of a physical system in terms of its motion as a function of time.[1] More specifically, the equations of motion describe the behaviour of a physical system as a set of mathematical functions in terms of dynamic variables: normally spatial coordinates and time are used, but others are also possible, such as momentum components and time. The most general choice are generalized coordinates which can be any convenient variables characteristic of the physical system.[2] The functions are defined in a Euclidean space in classical mechanics, but are replaced by curved spaces in relativity. If the dynamics of a system is known, the equations are the solutions to the differential equations describing the motion of the dynamics.

There are two main descriptions of motion: dynamics and kinematics. Dynamics is general, since momenta, forces and energy of the particles are taken into account. In this instance, sometimes the term refers to the differential equations that the system satisfies (e.g., Newton's second law or Euler–Lagrange equations), and sometimes to the solutions to those equations.

However, kinematics is simpler as it concerns only spatial and time-related variables. In circumstances of constant acceleration, these simpler equations of motion are usually referred to as the "SUVAT" equations, arising from the definitions of kinematic quantities: displacement (S), initial velocity (U), final velocity (V), acceleration (A), and time (T). (see below).

Equations of motion can therefore be grouped under these main classifiers of motion. In all cases, the main types of motion are translations, rotations, oscillations, or any combinations of these.

Historically, equations of motion initiated in classical mechanics and the extension to celestial mechanics, to describe the motion of massive objects. Later they appeared in electrodynamics, when describing the motion of charged particles in electric and magnetic fields. With the advent of general relativity, the classical equations of motion became modified. In all these cases the differential equations were in terms of a function describing the particle's trajectory in terms of space and time coordinates, as influenced by forces or energy transformations.[3] However, the equations of quantum mechanics can also be considered equations of motion, since they are differential equations of the wavefunction, which describes how a quantum state behaves analogously using the space and time coordinates of the particles. There are analogs of equations of motion in other areas of physics, notably waves. These equations are explained below.

Introduction

Qualitative

Equations of motion generally involve:

- a differential equation of motion, usually identified as some physical law and applying definitions of physical quantities, is used to set up an equation for the problem,

- setting the boundary and initial value conditions,

- a function of the position (or momentum) and time variables, describing the dynamics of the system,

- solving the resulting differential equation subject to the boundary and initial conditions.

The differential equation is a general description of the application and may be adjusted appropriately for a specific situation, the solution describes exactly how the system will behave for all times after the initial conditions, and according to the boundary conditions.[1][4]

Quantitative

In Newtonian mechanics, an equation of motion M takes the general form of a second order ordinary differential equation (ODE) in the position r (see below for details) of the object:

where t is time, and each overdot denotes a time derivative.

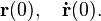

The initial conditions are given by the constant values at t = 0:

Another dynamical variable is the momentum p of the object, which can be used instead of r (though less commonly), i.e. a second order ODE in p:

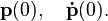

with initial conditions (again constant values)

The solution r (or p) to the equation of motion, combined with the initial values, describes the system for all times after t = 0. For more than one particle, there are separate equations for each (this is contrary to a statistical ensemble of many particles in statistical mechanics, and a many-particle system in quantum mechanics - where all particles are described by a single probability distribution). Sometimes, the equation will be linear and can be solved exactly. However in general, the equation is non-linear, and may lead to chaotic behaviour depending on how sensitive the system is to the initial conditions.

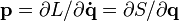

In the generalized Lagrangian mechanics, the generalized coordinates q (or generalized momenta p) replace the ordinary position (or momentum). Hamiltonian mechanics is slightly different, there are two first order equations in the generalized coordinates and momenta:

where q is a tuple of generalized coordinates and similarly p is the tuple of generalized momenta. The initial conditions are similarly defined.

Kinematic equations for one particle

Kinematic quantities

From the instantaneous position r = r (t), instantaneous meaning at an instant value of time t, the instantaneous velocity v = v (t) and acceleration a = a (t) have the general, coordinate-independent definitions;[5]

Notice that velocity always points in the direction of motion, in other words for a curved path it is the tangent vector. Loosely speaking, first order derivatives are related to tangents of curves. Still for curved paths, the acceleration is directed towards the center of curvature of the path. Again, loosely speaking, second order derivatives are related to curvature.

The rotational analogues are the angular position (angle the particle rotates about some axis) θ = θ(t), angular velocity ω = ω(t), and angular acceleration a = a(t):

where

is a unit axial vector, pointing parallel to the axis of rotation,  is the unit vector in direction of r, and

is the unit vector in direction of r, and  is the unit vector tangential to the angle. In these rotational definitions, the angle can be any angle about the specified axis of rotation. It is customary to use θ, but this does not have to be the polar angle used in polar coordinate systems.

is the unit vector tangential to the angle. In these rotational definitions, the angle can be any angle about the specified axis of rotation. It is customary to use θ, but this does not have to be the polar angle used in polar coordinate systems.

The following relations hold for a point-like particle, orbiting about some axis with angular velocity ω:[6]

where r is a radial position, v the tangential velocity of the particle, and a the particle's acceleration. More generally, these relations hold for each point in a rotating continuum rigid body.

Uniform acceleration

Constant linear acceleration

These equations apply to a particle moving linearly, in three dimensions in a straight line, with constant acceleration.[7] Since the vectors are collinear (parallel, and lie on the same line) - only the magnitudes of the vectors are necessary, hence non-bold letters are used for magnitudes, and because the motion is along a straight line, the problem effectively reduces from three dimensions to one.

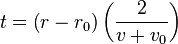

Two arise from integrating the definitions of velocity and acceleration:[7]

in magnitudes:

One is the average velocity - since the velocity increases linearly, the average velocity multiplied by time is the distance travelled while increasing the velocity from v0 to v (this can be illustrated graphically by plotting velocity against time as a straight line graph):

in magnitudes

From [3]

substituting for t in [1]:

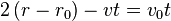

From [3]:

substituting into [2]:

Usually only the first 4 are needed, the fifth is optional.

where r0 and v0 are the particle's initial position and velocity, r, v, a are the final position (displacement), velocity and acceleration of the particle after the time interval.

Here a is constant acceleration, or in the case of bodies moving under the influence of gravity, the standard gravity g is used. Note that each of the equations contains four of the five variables, so in this situation it is sufficient to know three out of the five variables to calculate the remaining two.

SUVAT equations

In elementary physics the above formulae are frequently written as:

where u has replaced v0, s replaces r, and s0 = 0. They are often referred to as the "SUVAT" equations, where "SUVAT" is an acronym from the variables: s = displacement (s0 = initial displacement), u = initial velocity, v = final velocity, a = acceleration, t = time.[8][9]

Applications

Elementary and frequent examples in kinematics involve projectiles, for example a ball thrown upwards into the air. Given initial speed u, one can calculate how high the ball will travel before it begins to fall. The acceleration is local acceleration of gravity g. At this point one must remember that while these quantities appear to be scalars, the direction of displacement, speed and acceleration is important. They could in fact be considered as uni-directional vectors. Choosing s to measure up from the ground, the acceleration a must be in fact −g, since the force of gravity acts downwards and therefore also the acceleration on the ball due to it.

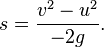

At the highest point, the ball will be at rest: therefore v = 0. Using equation [4] in the set above, we have:

Substituting and cancelling minus signs gives:

Constant circular acceleration

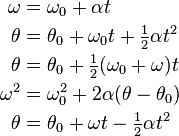

The analogues of the above equations can be written for rotation. Again these axial vectors must all be parallel (to the axis of rotation), so only the magnitudes of the vectors are necessary:

where α is the constant angular acceleration, ω is the angular velocity, ω0 is the initial angular velocity, θ is the angle turned through (angular displacement), θ0 is the initial angle, and t is the time taken to rotate from the initial state to the final state.

General planar motion

These are the kinematic equations for a particle traversing a path in a plane, described by position r = r(t).[10] They are actually no more than the time derivatives of the position vector in plane polar coordinates in the context of physical quantities (like angular velocity ω).

The position, velocity and acceleration of the particle are respectively:

where  are the polar unit vectors. Notice for a the components (–rω2) and 2ωdr/dt are the centripetal and Coriolis accelerations respectively.

are the polar unit vectors. Notice for a the components (–rω2) and 2ωdr/dt are the centripetal and Coriolis accelerations respectively.

Special cases of motion described be these equations are summarized qualitatively in the table below. Two have already been discussed above, in the cases that either the radial components or the angular components are zero, and the non-zero component of motion describes uniform acceleration.

| State of motion | Constant r | Linear r | Quadratic r | Non-linear r |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Constant θ | Stationary | Uniform translation (constant translational velocity) | Uniform translational acceleration | Non-uniform translation |

| Linear θ | Uniform angular motion in a circle (constant angular velocity) | Uniform angular motion in a spiral, constant radial velocity | Angular motion in a spiral, constant radial acceleration | Angular motion in a spiral, varying radial acceleration |

| Quadratic θ | Uniform angular acceleration in a circle | Uniform angular acceleration in a spiral, constant radial velocity | Uniform angular acceleration in a spiral, constant radial acceleration | Uniform angular acceleration in a spiral, varying radial acceleration |

| Non-linear θ | Non-uniform angular acceleration in a circle | Non-uniform angular acceleration

in a spiral, constant radial velocity |

Non-uniform angular acceleration

in a spiral, constant radial acceleration |

Non-uniform angular acceleration

in a spiral, varying radial acceleration |

General 3d motion

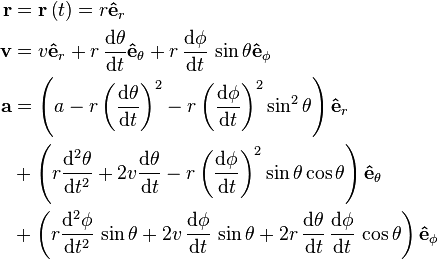

It is certainly possible to derive analogue equations for motion in 3d space, but the equations become more complicated and unwieldy. Using the spherical coordinates (r, θ, ϕ) with corresponding unit vectors  , the position, velocity, and acceleration are respectively:

, the position, velocity, and acceleration are respectively:

In the case of a constant ϕ this reduces to the planar equations above.

Harmonic motion of one particle

Translation

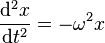

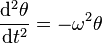

The kinematic equation of motion for a simple harmonic oscillator (SHO), oscillating in one dimension (the ±x direction) in a straight line is:

where ω is the angular frequency of the oscillatory motion, related to the general frequency f and the time period T (time taken for one cycle of oscillation):

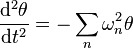

Many systems approximately execute simple harmonic motion (SHM). The complex harmonic oscillator is a superposition of simple harmonic oscillators:[7]

It is possible for simple harmonic motions to occur in any direction:[11]

known as a multidimensional harmonic oscillator. In cartesian coordinates, each component of the position will be a superposition of sinusiodal SHM.

Rotation

The rotational analogue of SHM in a straight line is angular oscillation about an axle or fulcrum:

where ω is still the angular frequency of the oscillatory motion - though not the angular velocity which is the rate of change of θ.

This form can be identified (at least approximately) as libration. The complex analogue is again a superposition of simple harmonic oscillators:

Dynamic equations of motion

Newtonian mechanics

It may be simple to write down the equations of motion in vector form using Newton's laws of motion, but the components may vary in complicated ways with spatial coordinates and time, and solving them is not easy. Often there is an excess of variables to solve for the problem completely, so Newton's laws are not the most efficient method for generally finding and solving for the motion of a particle. In simple cases of rectangular geometry, the use of Cartesian coordinates works fine, but other coordinate systems can become dramatically complex.

Newton's second law for translation

The first developed and most famous is Newton's second law of motion, there are several ways to write and use it, the most general is:[12]

where p = p(t) is the momentum of the particle and F = F(t) is the resultant external force acting on the particle (not any force the particle exerts) - in each case at time t. The law is also written more famously as:

since m is a constant in Newtonian mechanics. However the momentum form is preferable since this is readily generalized to more complex systems, generalizes to special and general relativity (see four-momentum), and since momentum is a conserved quantity; with deeper fundamental significance than the position vector or its time derivatives.[12]

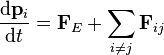

For a number of particles (see many body problem), the equation of motion for one particle i influenced by other particles is:[5][13]

where pi = momentum of particle i, Fij = force on particle i by particle j, and FE = resultant external force (due to any agent not part of system). Particle i does not exert a force on itself.

Newton's second law for rotation

For rigid bodies, Newton's second law for rotation takes the same form as for translation:[14]

where L is the angular momentum. Analogous to force and acceleration:

where I is the moment of inertia tensor. Likewise, for a number of particles, the equation of motion for one particle i is:[15]

where Li = angular momentum of particle i, τij = torque on particle i by particle j, and τE = resultant external torque (due to any agent not part of system). Particle i does not exert a torque on itself.

Applications

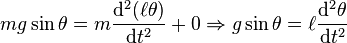

Some examples[11] of Newton's law include describing the motion of a pendulum:

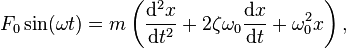

a damped, driven harmonic oscillator:

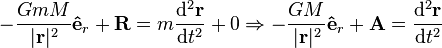

or a ball thrown in the air, in air currents (such as wind) described by a vector field of resistive forces R = R(x, y, z, t):

where G = gravitational constant, M = mass of the Earth and A is the acceleration of the projectile due to the air currents at position r and time t. Newton's law of gravity has been used. The mass m of the ball cancels.

Eulerian mechanics

Euler developed Euler's laws of motion, analogous to Newton's laws, for the motion of rigid bodies.

Newton–Euler equations

The Newton–Euler equations combine Euler's equations into one.

Analytical mechanics

More effective equations of motion than Newton's laws are below.

Constraints and motion

Using all three coordinates of 3d space is unnecessary if there are constraints on the system. Generalized coordinates q(t) = [q1(t), q2(t) ... qN(t)], where N is the total number of degrees of freedom the system has, are any set of coordinates used to define the configuration of the system, in the form of arc lengths or angles. They are a considerable simplification to describe motion since they take advantage of the intrinsic constraints that limit the system's motion - i.e. the number of coordinates is reduced to a minimum, rather than demanding rote algebra to describe the constraints and the motion using all three coordinates.

Corresponding to generalized coordinates are:

- their time derivatives, the generalized velocities:

,

, - conjugate "generalized" momenta:

,

,

(see matrix calculus for the denominator notation) where

- the Lagrangian is a function of the configuration q, the rate of change of configuration dq/dt, and time t:

![L=L\left[{\mathbf {q}}(t),{\mathbf {{\dot {q}}}}(t),t\right]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/2/9/9/d/299db21d55119e549fe90a6fc5d4c157.png) ,

, - the Hamiltonian is a function of the configuration q, motion p, and time t:

![H=H\left[{\mathbf {q}}(t),{\mathbf {p}}(t),t\right]](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/f/c/c/3/fcc31da013d9cfe8ff9a29018a864355.png) , and

, and - Hamilton's principal function, also called the classical action is a functional of L:

![S[{\mathbf {q}},t]=\int _{{t_{1}}}^{{t_{2}}}L({\mathbf {q}},{\mathbf {{\dot {q}}}},t){{\rm {d}}}t](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/4/6/5/0/4650945369745f04bd77429c9138b1f0.png) .

.

The Lagrangian or Hamiltonian function is set up for the system using the q and p variables, then these are inserted into the Euler-Lagrange or Hamilton's equations to obtain differential equations of the system. These are solved for the coordinates and momenta.

Generalized classical equations of motion

All classical equations of motion can be derived from this variational principle:

stating the path the system takes through the configuration space is the one with the least action.

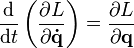

- Euler-Lagrange equations

The Euler-Lagrange equations are:[2][16]

After substituting for the Lagrangian, evaluating the partial derivatives, and simplifying, a second order ODE in each qi is obtained.

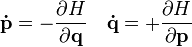

- Hamilton's equations

Hamilton's equations are:[2][16]

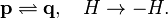

Notice the equations are symmetric (remain in the same form) by making these interchanges simultaneously:

After substituting the Hamiltonian, evaluating the partial derivatives, and simplifying, two first order ODEs in qi and pi are obtained.

Hamilton's formalism can be rewritten as:[2]

Although the equation has a simple form, it's actually a non-linear PDE, first order in N + 1 variables, rather than 2N such equations. Due to the action S, it can be used to identify conserved quantities for mechanical systems, even when the mechanical problem itself cannot be solved fully, because any differentiable symmetry of the action of a physical system has a corresponding conservation law, a theorem due to Emmy Noether.

Electrodynamics

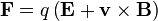

In electrodynamics, the force on a charged particle of charge q is the Lorentz force:[17]

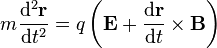

Combining with Newton's second law gives a first order differential equation of motion, in terms of position of the particle:

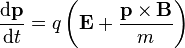

or its momentum:

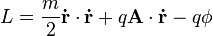

The same equation can be obtained using the Lagrangian (and applying Lagrange's equations above) for a charged particle of mass m and charge q:[18]

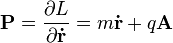

where A and ϕ are the electromagnetic scalar and vector potential fields. The Lagrangian indicates an additional detail: the canonical momentum in Lagrangian mechanics is given by:

instead of just mv, implying the motion of a charged particle is fundamentally determined by the mass and charge of the particle. The Lagrangian expression was first used to derive the force equation.

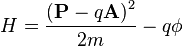

Alternatively the Hamiltonian (and substituting into the equations):[16]

can derive the Lorentz force equation.

General relativity

Geodesic equation of motion

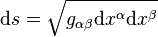

The above equations are valid in flat spacetime. In curved space spacetime, things become mathematically more complicated since there is no straight line; this is generalized and replaced by a geodesic of the curved spacetime (the shortest length of curve between two points). For curved manifolds with a metric tensor g, the metric provides the notion of arc length (see line element for details), the differential arc length is given by:[19]

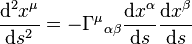

and the geodesic equation is a second-order differential equation in the coordinates, the general solution is a family of geodesics:[20]

where Γμαβ is a Christoffel symbol of the second kind, which contains the metric (with respect to the coordinate system).

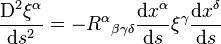

Given the mass-energy distribution provided by the stress–energy tensor Tαβ, the Einstein field equations are a set of non-linear second-order partial differential equations in the metric, and imply the curvature of space time is equivalent to a gravitational field (see principle of equivalence). Mass falling in curved spacetime is equivalent to a mass falling in a gravitational field - because gravity is a fictitious force. The relative acceleration of one geodesic to another in curved spacetime is given by the geodesic deviation equation:

where ξα = (x2)α − (x1)α is the separation vector between two geodesics, D/ds (not just d/ds) is the covariant derivative, and Rαβγδ is the Riemann curvature tensor, containing the Christoffel symbols. In other words, the geodesic deviation equation is the equation of motion for masses in curved spacetime, analogous to the Lorentz force equation for charges in an electromagnetic field.[21]

For flat spacetime, the metric is a constant tensor so the Christoffel symbols vanish, and the geodesic equation has the solutions of straight lines. This is also the limiting case when masses move according to Newton's law of gravity.

Spinning objects

In general relativity, rotational motion is described by the relativistic angular momentum tensor, including the spin tensor, which enter the equations of motion under covariant derivatives with respect to proper time. The Mathisson–Papapetrou–Dixon equations describe the motion of spinning objects moving in a gravitational field.

Analogues for waves and fields

Unlike the equations of motion for describing particle mechanics, which are often ordinary differential equations, the analogous equations governing the dynamics of waves and fields are always partial differential equations, since the waves or fields are functions of space and time. Sometimes in the following contexts, the wave or field equations are also called "equations of motion".

Field equations

Equations that describe the spatial dependence and time evolution of fields are called field equations. These include

- the Navier–Stokes equations for the velocity field of a fluid,

- Maxwell's equations for the electromagnetic field,

- the Einstein field equation for gravitation (Newton's law of gravity is a special case for weak gravitational fields and low velocities of particles),

Wave equations

Equations of wave motion are called wave equations. The solutions to a wave equation give the time-evolution and spatial dependence of the amplitude. Boundary conditions determine if the solutions describe traveling waves or standing waves.

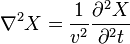

From classical equations of motion and field equations; mechanical, gravitational wave, and electromagnetic wave equations can be derived. The general linear wave equation in 3d is:

where X = X(r, t) is any mechanical or electromagnetic field amplitude, say:[22]

- the transverse or longitudinal displacement of a vibrating rod, wire, cable, membrane etc.,

- the fluctuating pressure of a medium, sound pressure,

- the electric fields E or D, or the magnetic fields B or H,

- the voltage V or current I in an alternating current circuit,

and v is the phase velocity. Non-linear equations model the dependence of phase velocity on amplitude, replacing v by v(X). There are other linear and non-linear wave equations for very specific applications, see for example the Korteweg–de Vries equation.

Quantum theory

In quantum theory, the wave and field concepts both appear.

In quantum mechanics, in which particles also have wave-like properties according to wave-particle duality, the analogue of the classical equations of motion (Newton's law, Euler–Lagrange equation, Hamilton–Jacobi equation, etc.) is the Schrödinger equation in its most general form:

where Ψ is the wavefunction of the system,  is the quantum Hamiltonian operator, rather than a function as in classical mechanics, and ħ is the Planck constant divided by 2π. Setting up the Hamiltonian and inserting it into the equation results in a wave equation, the solution is the wavefunction as a function of space and time. The Schrödinger equation itself reduces to the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in when one considers the correspondence principle, in the limit that ħ becomes zero.

is the quantum Hamiltonian operator, rather than a function as in classical mechanics, and ħ is the Planck constant divided by 2π. Setting up the Hamiltonian and inserting it into the equation results in a wave equation, the solution is the wavefunction as a function of space and time. The Schrödinger equation itself reduces to the Hamilton–Jacobi equation in when one considers the correspondence principle, in the limit that ħ becomes zero.

Applying special relativity to quantum mechanics results in their unification as relativistic quantum mechanics; this is achieved by inserting relativistic Hamiltonians into the Schrödinger equation, leading to relativistic wave equations.

In the context of relativistic and non-relativistic quantum field theory, in which particles are interpreted and treated as fields rather than waves, the Schrödinger equation above has solutions Ψ which are interpreted as fields.

Throughout all aspects of quantum theory, relativistic or non-relativistic, there are various formulations alternative to the Schrödinger equation that govern the time evolution and behavior of a quantum system, for instance:

- the Heisenberg equation of motion resembles the time evolution of classical observables as functions of position, momentum, and time, if one replaces dynamical observables by their quantum operators and the classical Poisson bracket by the commutator,

- the phase space formulation closely follows classical Hamiltonian mechanics, placing position and momentum on equal footing,

- the Feynman path integral formulation extends the principle of least action to quantum mechanics and field theory, placing emphasis on the use of a Lagrangians rather than Hamiltonians.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Encyclopaedia of Physics (second Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC Publishers, 1991, ISBN (Verlagsgesellschaft) 3-527-26954-1 (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Analytical Mechanics, L.N. Hand, J.D. Finch, Cambridge University Press, 2008, ISBN 978-0-521-57572-0

- ↑ Halliday, David; Resnick, Robert; Walker, Jearl (2004-06-16). Fundamentals of Physics (7 Sub ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-23231-9.

- ↑ Classical Mechanics, T.W.B. Kibble, European Physics Series, 1973, ISBN 07-084018-0

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dynamics and Relativity, J.R. Forshaw, A.G. Smith, Wiley, 2009, ISBN 978-0-470-01460-8

- ↑ M.R. Spiegel, S. Lipcshutz, D. Spellman (2009). Vector Analysis. Schaum’s Outlines (2nd ed.). McGraw Hill. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-07-161545-7.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 Essential Principles of Physics, P.M. Whelan, M.J. Hodgeson, second Edition, 1978, John Murray, ISBN 0-7195-3382-1

- ↑ Hanrahan, Val; Porkess, R (2003). Additional Mathematics for OCR. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 219. ISBN 0-340-86960-7.

- ↑ Keith Johnson (2001). Physics for you: revised national curriculum edition for GCSE (4th ed.). Nelson Thornes. p. 135. ISBN 978-0-7487-6236-1. "The 5 symbols are remembered by "suvat". Given any three, the other two can be found."

- ↑ 3000 Solved Problems in Physics, Schaum Series, A. Halpern, Mc Graw Hill, 1988, ISBN 978-0-07-025734-4

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 The Physics of Vibrations and Waves (3rd edition), H.J. Pain, John Wiley & Sons, 1983, ISBN 0-471-90182-2

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 An Introduction to Mechanics, D. Kleppner, R.J. Kolenkow, Cambridge University Press, 2010, p. 112, ISBN 978-0-521-19821-9

- ↑ Encyclopaedia of Physics (second Edition), R.G. Lerner, G.L. Trigg, VHC publishers, 1991, ISBN (VHC Inc.) 0-89573-752-3

- ↑ "Mechanics, D. Kleppner 2010"

- ↑ "Relativity, J.R. Forshaw 2009"

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Classical Mechanics (second edition), T.W.B. Kibble, European Physics Series, 1973, ISBN 07-084018-0

- ↑ Electromagnetism (second edition), I.S. Grant, W.R. Phillips, Manchester Physics Series, 2008 ISBN 0-471-92712-0

- ↑ Classical Mechanics (second Edition), T.W.B. Kibble, European Physics Series, Mc Graw Hill (UK), 1973, ISBN 07-084018-0.

- ↑ C.B. Parker (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (second ed.). p. 1199. ISBN 0-07-051400-3.

- ↑ C.B. Parker (1994). McGraw Hill Encyclopaedia of Physics (second ed.). p. 1200. ISBN 0-07-051400-3.

- ↑ J.A. Wheeler, C. Misner, K.S. Thorne (1973). Gravitation. W.H. Freeman & Co. pp. 34–35. ISBN 0-7167-0344-0.

- ↑ H.D. Young, R.A. Freedman (2008). University Physics (12th Edition ed.). Addison-Wesley (Pearson International). ISBN 0-321-50130-6.

![M\left[{\mathbf {r}}(t),{\mathbf {{\dot {r}}}}(t),{\mathbf {{\ddot {r}}}}(t),t\right]=0](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/e/7/b/a/e7ba985a7505ba44d66d43506f42a33c.png)

![{\tilde {M}}\left[{\mathbf {p}}(t),{\mathbf {{\dot {p}}}}(t),{\mathbf {{\ddot {p}}}}(t),t\right]=0](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/6/9/1/a/691a1895c534eb8d3881f6e186bf2e9e.png)

![M\left[{\mathbf {q}}(t),{\mathbf {{\dot {q}}}}(t),t\right]=0,\quad {\tilde {M}}\left[{\mathbf {p}}(t),{\mathbf {{\dot {p}}}}(t),t\right]=0](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/d/7/7/5/d77528626c7c038b15aa9c80d9c6a052.png)

![{\begin{aligned}{\mathbf {v}}&=\int {\mathbf {a}}{{\rm {d}}}t={\mathbf {a}}t+{\mathbf {v}}_{0}\quad [1]\\{\mathbf {r}}&=\int ({\mathbf {a}}t+{\mathbf {v}}_{0}){{\rm {d}}}t={\frac {{\mathbf {a}}t^{2}}{2}}+{\mathbf {v}}_{0}t+{\mathbf {r}}_{0}\quad [2]\\\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/7/e/6/b7e60896185c6f45abfdbd22f1a1c52c.png)

![{\begin{aligned}v&=at+v_{0}\quad [1]\\r&={\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}+v_{0}t+r_{0}\quad [2]\\\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/b/a/5/f/ba5ff802402425311f2cf0faedd1b2a0.png)

![{\mathbf {r}}=\left({\frac {{\mathbf {v}}+{\mathbf {v}}_{0}}{2}}\right)t\quad [3]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/a/7/d/1/a7d13b777beace9c0bb336f5f776604e.png)

![r=r_{0}+\left({\frac {v+v_{0}}{2}}\right)t\quad [3]\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/4/a/b/54abcf498cf68903d7f49c844729eca9.png)

![{\begin{aligned}v&=a\left(r-r_{0}\right)\left({\frac {2}{v+v_{0}}}\right)+v_{0}\\v\left(v+v_{0}\right)&=2a\left(r-r_{0}\right)+v_{0}\left(v+v_{0}\right)\\v^{2}+vv_{0}&=2a\left(r-r_{0}\right)+v_{0}v+v_{0}^{2}\\v^{2}&=v_{0}^{2}+2a\left(r-r_{0}\right)\quad [4]\\\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/0/b/4/e/0b4eaa8a82bde0f48020beb6716a9503.png)

![{\begin{aligned}r&={\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}+2r-2r_{0}-vt+r_{0}\\0&={\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}+r-r_{0}-vt\\r&=r_{0}+vt-{\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}\quad [5]\end{aligned}}\,\!](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/4/3/8/c/438c1ecab6ec236bbbe99e8d876ec5d6.png)

![{\begin{aligned}v&=at+v_{0}\quad [1]\\r&=r_{0}+v_{0}t+{\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}\quad [2]\\r&=r_{0}+\left({\frac {v+v_{0}}{2}}\right)t\quad [3]\\v^{2}&=v_{0}^{2}+2a\left(r-r_{0}\right)\quad [4]\\r&=r_{0}+vt-{\frac {{a}t^{2}}{2}}\quad [5]\\\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/c/f/0/d/cf0d7f172673c522d82c76483afa3597.png)

![{\begin{aligned}v&=u+at\quad [1]\\s&=ut+{\frac {1}{2}}at^{2}\quad [2]\\s&={\frac {1}{2}}(u+v)t\quad [3]\\v^{2}&=u^{2}+2as\quad [4]\\s&=vt-{\frac {1}{2}}at^{2}\quad [5]\\\end{aligned}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/4/3/6/3/436357594271ec28379aa9b0e6342b5a.png)