Enhanced geothermal system

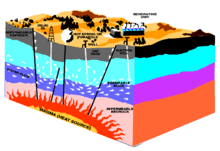

An enhanced geothermal system (EGS) generates geothermal electricity without the need for natural convective hydrothermal resources. Until recently, geothermal power systems have exploited only resources where naturally occurring heat, water, and rock permeability are sufficient to allow energy extraction.[1] However, by far the most geothermal energy within reach of conventional techniques is in dry and impermeable rock.[2] EGS technologies enhance and/or create geothermal resources in this hot dry rock (HDR) through 'hydraulic stimulation'.

When natural cracks and pores do not allow economic flow rates, the permeability can be enhanced by pumping high-pressure cold water down an injection well into the rock. The injection increases the fluid pressure in the naturally fractured rock, mobilizing shear events that enhance the system's permeability. As there is a continuous circulation, neither is a high permeability required, nor are proppants required to maintain the fractures in an open state. This process, termed hydro-shearing,[3] perhaps to differentiate it from an equivalent procedure. Nevertheless it is substantially the same as hydraulic tensile fracturing used in the oil and gas industry.

Water travels through fractures in the rock, capturing the rock's heat until forced out of a second borehole as very hot water. The water's heat is converted into electricity using either a steam turbine or a binary power plant system.[4] All of the water, now cooled, is injected back into the ground to heat up again in a closed loop.

EGS technologies, like hydrothermal geothermal, can function as baseload resources that produce power 24 hours a day, like a fossil fuel plant. Unlike hydrothermal, EGS appears to be feasible anywhere in the world, depending on the economic limits of drill depth. Good locations are over deep granite covered by a 3–5 kilometres (1.9–3.1 mi) layer of insulating sediments that slow heat loss.[5] EGS wells are expected to have a useful life of 20 to 30 years before the outflow temperature drops about 10 c (18 f) and the well becomes uneconomic.

EGS systems are currently being developed and tested in France, Australia, Japan, Germany, the U.S. and Switzerland. The largest EGS project in the world is a 25-megawatt demonstration plant currently being developed in Cooper Basin, Australia. Cooper Basin has the potential to generate 5,000–10,000 MW.

EGS industry

Commercial projects are currently either operational or under development in the UK, Australia, the United States, France and Germany.

The largest project in the world is being developed in Australia's Cooper Basin by Geodynamics.[6] The Cooper Basin project has the potential to develop 5–10 GW. Australia now has 33 firms either exploring for, drilling, or developing EGS projects. Australia's industry has been greatly aided by a national Renewable Portfolio Standard of 25% renewables by 2025, a vibrant Green Energy Credit market, and supportive collaboration between government, academia, and industry.

Germany's now 25 cent/kWh Feed-In Tariff (FIT) for geothermal energy has led to a surge in geothermal development, despite Germany's relatively poor geothermal resource. The Landau partial EGS project is profitable today under the FIT. Drawing on the success of the Landau project, EGS Energy[7] are developing sites in the UK. The first of these will be built in collaboration with the Eden Project.

The AltaRock Energy effort is a demonstration project being conducted to prove out the company's proprietary technology at the site of an existing geothermal project owned and operated by NCPA in The Geysers, and does not include power generation. However, any steam produced by the project will be supplied to NCPA's flash turbines under a long-term contract.[8]

| Project | Type | Country | Size (MW) | Plant Type | Depth (km) | Developer | Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Soultz | R&D | France (EU) | 1.5 | Binary | 4.2 | ENGINE | Operational |

| Landau | Commercial | Germany (EU) | 3 | Binary | 3.3 | ? | Operational |

| Aardwarmte Den Haag | Commercial | Netherlands (EU) | 6 MW(th) | Thermal | 2.0 | Municipality, Eneco, E.On Benelux, IF Tech | Operational 2012; wells tested 2010. Heating 4,000 homes in central city.[9][10][11] |

| Desert Peak | R&D | United States | 11–50 | Binary | DOE, Ormat, GeothermEx | Development | |

| Paralana (Phase 1) | Commercial | Australia | 7–30 | Binary | 4.1 | Petratherm | Drilling |

| Cooper Basin | Commercial | Australia | 250–500 | Kalina | 4.3 | Geodynamics | Drilling |

| The Geysers | Demonstration | United States | (Unknown) | Flash | 3.5 – 3.8 | AltaRock Energy, NCPA | Suspended (Oct 2009)[12] |

| Bend, Oregon | Demonstration | United States | (Unknown) | 2 - 3 | AltaRock Energy, Davenport Newberry, DOE | Permitting (Mar 2010)[13] | |

| Ogachi | R&D | Japan | (Unknown) | 1.0 – 1.1 | CO2 experiments[14] | ||

| United Downs, Redruth | Commercial | United Kingdom | 10 MW | Binary | 4.5 | Geothermal Engineering Ltd | Fundraising[15] |

| Eden Project | Commercial | United Kingdom | 3 MW | Binary | 3–4 | EGS Energy Ltd. | Fundraising[16] |

Research and development

Australia

The Australian government has provided research funding for the development of Hot Dry Rock technology.[17]

On 30 May 2007, then Australian opposition environmental spokesperson and former Minister for the Environment, Heritage and the Arts Peter Garrett announced that if elected at the 2007 Australian Federal Election, the Australian Labor Party would use taxpayer money to subsidise putting the necessary drilling rigs in place. In an interview, he promised:

"There are some technical difficulties and challenges there, but those people who are keen on getting Australia into geothermal say we've got this great access to resource and one of the things, interestingly, that's held them back is not having the capacity to put the drilling plants in place. And so what we intend this $50 million to go towards is to provide one-for-one dollars. Match $1 from us, $1 from the industry so that they can get these drilling rigs on to site and really get the best sites identified and get the industry going."[18]

European Union

The EU's EGS R&D project at Soultz-sous-Forêts, France, has recently connected its 1.5 MW demonstration plant to the grid. The Soultz project has explored the connection of multiple stimulated zones and the performance of triplet well configurations (1 injector/2 producers).[19]

Induced seismicity in Basel led to the cancellation of the EGS project there.

The Portuguese government awarded, in December 2008, an exclusive license to Geovita Ltd to prospect and explore geothermal energy in one of the best areas in continental Portugal. An area of about 500 square kilometers is being studied by Geovita together with the Earth Sciences department of the University of Coimbra's Science and Technology faculty, and the installation of an Enhanced Geothermal System (EGS) is foreseen.

United Kingdom

Cornwall is set to host a 3MW demonstration project, based at the Eden Project, that could pave the way for a series of 50-MW commercial-scale geothermal power stations in suitable areas across the country.[20][21]

A commercial-scale project near Redruth is also planned. The plant, which has been granted planning permission,[22] would generate 10 MW of electricity and 55 MW of thermal energy and is scheduled to become operational in 2013–2014.[23][24]

United States

Early days — Fenton Hill

The United States pioneered the first EGS effort — then termed Hot Dry Rock — at Fenton Hill, New Mexico with a project run by the federal Los Alamos Laboratory.[25] It was the first attempt anywhere to make a deep, full-scale HDR reservoir, and efforts there spanned 1974 through 1992, in two phases. Ultimately, the project was unable to generate net energy and was terminated.

Working at the edges—using EGS technology to improve hydrothermal resources

EGS funding languished for the next few years, and by the next decade, US efforts focused on the less ambitious goal of improving the productivity of existing hydrothermal resources. According to the fiscal year 2004 Budget Request to Congress from DOE's Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy, [26]

EGS are engineered reservoirs that have been created to extract heat from economically unproductive geothermal resources. EGS technology includes those methods and equipment that enhance the removal of energy from a resource by increasing the productivity of the reservoir. Better productivity may result from improving the reservoir’s natural permeability and/or providing additional fluids to transport heat.[27]

In fiscal year 2002, this vision translated into completing "preliminary designs for five competitively selected projects employing EGS technology," and the selection of one project for "full-scale development" at the Coso Hot Springs geothermal field at the US Naval Weapons Air Station in China Lake, California, and two additional projects for "preliminary analysis from a new solicitation" at Desert Peak in Nevada and Glass Mountain in California. Funding for this effort totaled $1.5 million. [28]

In fiscal year 2003, $3.5 million was appropriated to launch the Coso project, with the aim of improving the permeability of an existing poorly performing well, and to complete the conceptual design and feasibility studies at the Desert Peak and Glass Mountain sites.[29]

The fiscal year 2004 request for $6 million was to "[s]tep up work on EGS cost-shared projects' at the three sites, to include "drilling and reservoir stimulation experiments" at one and drilling a production well at another.[29]

The US Department of Energy USDOE issued two Funding Opportunity Announcements (FOAs) on March 4, 2009 for enhanced geothermal systems (EGS). Together, the two FOAs offer up to $84 million over six years, including $20 million in fiscal year 2009 funding, although future funding is subject to congressional appropriations. [30]

The DOE followed up with another FOA on March 27, 2009, of stimulus funding from the American Reinvestment and Recovery Act for $350 million, including $80 million aimed specifically at EGS projects,[31]

Induced seismicity

Some induced seismicity is inevitable and expected in EGS, which involves pumping fluids at pressure to enhance or create permeability through the use of hydro-shearing techniques. In contrast to induction of tensile failure, the purpose of hydraulic fracturing used in the oil and gas industries, EGS seeks to induce relatively small shear failure of the rock's existing joint set to create an optimum reservoir for the transfer of heat from the rock to the water in order to produce steam.[32][33] Seismicity events at the Geysers geothermal field in California have been strongly correlated with injection data.[34]

The case of induced seismicity in Basel merits special mention; it led the city (which is a partner) to suspend the project and conduct a seismic hazard evaluation, which resulted in the cancellation of the project in December 2009.[35]

Risks associated with "hydrofracturing induced seismicity are low compared to that of natural earthquakes, and can be reduced by careful management and monitoring" and "should not be regarded as an impediment to further development of the Hot Rock geothermal energy resource".[36]

CO2 EGS

The recently established Center for Geothermal Energy Excellence at the University of Queensland has been awarded AUD 18.3 million for EGS research, a large portion of which will be used to develop CO2 EGS technologies.

Research conducted at Los Alamos National Laboratories and Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories examined the use of supercritical CO2, instead of water, as the geothermal working fluid, with favorable results. CO2 has numerous advantages for EGS:

- Greater power output

- Minimized parasitic losses from pumping and cooling

- Carbon sequestration

- Minimized water use

EGS potential in the United States

A 2006 report by MIT,[37] and funded by the U.S. Department of Energy, conducted the most comprehensive analysis to date on the potential and technical status of EGS. The 18-member panel, chaired by Professor Jefferson Tester of MIT, reached several significant conclusions:

- Resource size: The report calculated the United States total EGS resources from 3–10 km of depth to be over 13,000 zettajoules, of which over 200 ZJ would be extractable, with the potential to increase this to over 2,000 ZJ with technology improvements — sufficient to provide all the world's current energy needs for several millennia.[37] The report found that total geothermal resources, including hydrothermal and geo-pressured resources, to equal 14,000 ZJ — or roughly 140,000 times the total U.S. annual primary energy use in 2005.

- Development potential: With a modest R&D investment of $1 billion over 15 years (or the cost of one coal power plant), the report estimated that 100 GWe (gigawatts of electricity) or more could be installed by 2050 in the United States. The report further found that "recoverable" resources (accessible with today's technology) were between 1.2–12.2 TW for the conservative and moderate recovery scenarios respectively.

- Cost: The report found that EGS could be capable of producing electricity for as low as 3.9 cents/kWh. EGS costs were found to be sensitive to four main factors: 1) Temperature of the resource, 2) Fluid flow through the system measured in liters/second, 3) Drilling costs, and 4) Power conversion efficiency.

See also

- Caprock

- Rosemanowes Quarry

- Geothermal energy in the United States

- Geothermal energy exploration in Central Australia

- Geothermal exploration

References

- ↑ Lund, John W. (June 2007), "Characteristics, Development and utilization of geothermal resources", Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin (Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology) 28 (2): 1–9, ISSN 0276-1084, retrieved 2009-04-16

- ↑ Duchane, Dave; Brown, Don (December 2002), "Hot Dry Rock (HDR) Geothermal Energy Research and Development at Fenton Hill, New Mexico", Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin (Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology) 23 (4): 13–19, ISSN 0276-1084, retrieved 2009-05-05

- ↑ [[http://energy.usgs.gov/other/geothermal/|Pierce, Brenda]] (2010-02-16). "Geothermal Energy Resources" (PowerPoint). National Association of Regulatory Utility Commissioners (NARUC). Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ↑ http://www1.eere.energy.gov/geothermal/egs_animation.html

- ↑ 20 slide presentation inc geothermal maps of Australia

- ↑ Beardsmore, Graeme (September 2007), "The Burgeoning Australian Geothermal Energy Industry", Geo-Heat Centre Quarterly Bulletin (Klamath Falls, Oregon: Oregon Institute of Technology) 28 (3): 20–26, ISSN 0276-1084, retrieved 2009-05-07

- ↑ http://www.egs-energy.com

- ↑ http://altarockenergy.com/AltaRockEnergy.2009-03-19.pdf

- ↑ City of The Hague website. 4 Jan. 2011. Drilling concludes for geothermal energy - Sustainable energy.

- ↑ CNBC Money Control. 21 Jan. 2011. Geothermal heats The Hague(Video).

- ↑ IF Tech. Undated flyer. Geothermal space heating in The Hague Geothermal space heating in The Hague.

- ↑ "AltaRock EGS Demonstration Project Status with NCPA at The Geysers". 2009-10-19. Retrieved 2011-03-19.

- ↑ Loralee Stevens. "AltaRock gets $25 million for Oregon project", North Bay Business Journal, Sausalito, November 9th, 2009 04:45am. Retrieved on 2010-03-31.

- ↑ Kaieda, H. et al (February 9–11, 2009), Field Experiments for Studying on CO2 Sequestration in Solid Minerals at the Ogachi HDR Geothermal Site, Japan, PROCEEDINGS, Thirty-Fourth Workshop on Geothermal Reservoir Engineering, Stanford, California: Stanford University, retrieved 2010-01-17

- ↑ "Plans unveiled for "UK’s first" commercial-scale geothermal plant", New Energy Focus, October 20, 2009

- ↑ "Nearly £3.5m to be invested in geothermal energy in Cornwall", Bude People, January 17, 2010

- ↑ http://www.ret.gov.au/energy/energy%20programs/cei/acre/gdp/Pages/default.aspx

- ↑ "Garrett discusses Labor's stance on climate change", Lateline, 30 May 2007

- ↑ See French Wikipedia: Soultz-sous-Forêts — Soultz is in the Alsace région of France.

- ↑ "Tories pledge support for deep geothermal energy projects". New Energy Focus (www.newenergyfocus.com). May 15, 2009. Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ Martin, Daniel (June 2, 2009). "Geothermal power plant that could run 5,000 British homes to be built in Cornwall". Daily Mail (London: Associated Newspapers Ltd). Retrieved 2009-06-11.

- ↑ "'Hot rocks' geothermal energy plant promises a UK first for Cornwall". Western Morning News. August 17, 2010-08-17. Retrieved 2010-08-17.

- ↑ "Energy firm plans to become first to power town with heat from deep underground". Daily Mail (London: www.dailymail.co.uk). October 14, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ↑ "Plans for geothermal plant at industrial estate are backed". This is Cornwall (www.thisiscornwall.co.uk). November 23, 2009. Retrieved 2010-01-21.

- ↑ Tester 2006, pp. 4–7 to 4–13

- ↑ "FY 2004 Congressional Budget Request – Energy Supply Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy". U.S Department of Energy. 2003-02-03. p. 244.

- ↑ FY2004DOE 2003, p. 131

- ↑ FY2004DOE 2003, pp. 131–131

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 FY2004DOE 2003, p. 132

- ↑ "EERE News: DOE to Invest up to $84 Million in Enhanced Geothermal Systems". 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ "Department of Energy – President Obama Announces Over $467 Million in Recovery Act Funding for Geothermal and Solar Energy Projects". 2009-05-27. Retrieved 2009-07-04.

- ↑ Tester 2006, pp. 4–5 to 4–6

- ↑ Tester 2006, pp. 8–9 to 8–10

- ↑ http://escholarship.org/uc/item/0t19709v The Impact of Injection on Seismicity at The Geysers Geothermal Field

- ↑ Glanz, James (2009-12-10), "Quake Threat Leads Swiss to Close Geothermal Project", The New York Times

- ↑ Geoscience Australia. "Induced Seismicity and Geothermal Power Development in Australia". Australian Government.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Tester, Jefferson W. (Massachusetts Institute of Technology) et al (2006). The Future of Geothermal Energy – Impact of Enhanced Geothermal Systems (EGS) on the United States in the 21st Century (14MB PDF). Idaho Falls: Idaho National Laboratory. ISBN 0-615-13438-6. Retrieved 2007-02-07.

External links

- EERE:

- Geothermal investment rocks says DLA Phillips Fox

- 20 slide presentation inc geothermal maps of Australia

- MEGSorg

- EGS at Google.org

| ||||||||||||||||||||