Endowment effect

In behavioral economics, the endowment effect (also known as divestiture aversion) is the hypothesis that people ascribe more value to things merely because they own them.[1] This is illustrated by the fact that people will pay more to retain something they own than to obtain something owned by someone else—even when there is no cause for attachment, or even if the item was only obtained minutes ago.

Examples

One of the most famous examples of the endowment effect in the literature is from a study by Kahneman, Knetsch & Thaler (1990)[2] where participants were given a mug and then offered the chance to sell it or trade it for an equally priced alternative good (pens). Kahneman et al. (1990)[2] found that participants' willingness to accept compensation for the mug (once their ownership of the mug had been established) was approximately twice as high as their willingness to pay for it.

Other examples of the endowment effect include work by Carmon and Ariely (2000)[3] who found that participants' hypothetical selling price (WTA) for NCAA final four tournament tickets were 14 times higher than their hypothetical buying price (WTP). Also, work by Hossain and List (Working Paper) discussed in the Economist (2010),[4] showed that workers worked harder to maintain ownership of a provisional awarded bonus than they did for a bonus framed as a potential yet-to-be-awarded gain. In addition to these examples, the endowment effect has been observed in a wide range of different populations using different goods (see Hoffman and Spitzer,1993 for a review [5]) including children (Harbaugh et al., 2001[6]) great apes (Kanngiesser, Santos, Hood, Call, 2011[7]), and new world monkeys (Lakshminaryanan, Chen & Santos, 2008[8]).

Background

Psychologists first noted the difference between consumers' WTP and WTA as early as the 1960s (Coombs, Bezembinder and Goode, 1967,[9] Slovic and Lichtenstein, 1968[10]). The term endowment effect however was first explicitly coined by the economist Richard Thaler (1980)[11] in reference to the under-weighting of opportunity costs as well as the inertia introduced into a consumer's choice processes when goods included in their endowment become more highly valued than goods that are not. In the years that followed, extensive investigations into the endowment effect have been conducted producing a wealth of interesting empirical and theoretical findings (Hoffman and Spitzer, 1993 for a review[5]).

Theoretical explanations

Loss aversion

The endowment effect due to the fact that once you own the item, forgoing it feels like a loss, and humans are loss-averse.[citation needed] The endowment effect contradicts the Coase theorem, and was described as inconsistent with standard economic theory which asserts that a person's willingness to pay (WTP) for a good should be equal to their willingness to accept (WTA) compensation to be deprived of the good, a hypothesis which underlies consumer theory and indifference curves.

Reference-dependent accounts

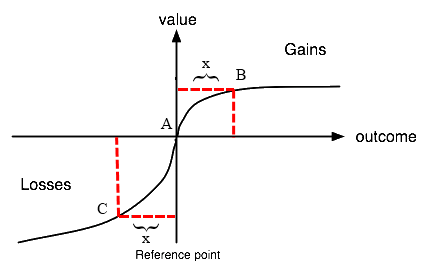

According to reference-dependent theories, consumers first evaluate the potential change in question as either being a gain or a loss. In line with prospect theory (Tversky and Kahneman, 1979[12]), changes that are framed as losses are weighed more heavily than are the changes framed as gains. Thus an individual owning "A" amount of a good, asked how much he/she would be willing to pay to acquire "B', would have a WTP that is lower than the WTA he/she would be willing to accept to sell (B-A) units simply because the value function for gains is less steep than the value function for losses.

Figure 1 presents this explanation in graphical form. An individual at point A, asked how much he/she would be willing to accept (WTA) as compensation to sell X units and move to point C, would demand greater compensation for that loss than he/she would be willing to pay for an equivalent gain of X units to move him/her to point B. Thus the difference between (B-A) and (C-A) would account for the endowment effect. In other words he/she expects more money while selling; but wants to pay less while buying the same amount of goods.

- Figure 1 : Prospect Theory and the Endowment Effect

Neoclassical explanations

Hanemann (1991),[13] develops a neoclassical explanation for the endowment effect, accounting for the effect without invoking prospect theory.

Figure 2 presents this explanation in graphical form. In the figure, two indifference curves for a particular good X and wealth are given. An individual asked how much he/she would be willing to pay to move from A where he/she has X0 of good X to point B, where he/she has the same wealth and X1 of good X, has his/her WTP represented by the vertical distance between C and B since the individual is indifferent about being at A or C. On the other hand, an individual asked to indicate how much he/she would be willing to accept to move from B to A has his/her WTA represented by the vertical distance between A and D as he/she is indifferent about either being at point B or D. Shogren et al. (1994)[14] has reported findings that lend support to Hanemann's hypothesis.

- Figure 2 : Hanemann's Endowment Effect Explanation

Connection-based theories

Connection-based theories propose that subjective feelings are responsible for an individual's reluctance to trade (i.e. the endowment effect). For example, receiving a mug may induce a minimal attachment to that item which an individual may be averse to breaking, resulting in an increase in the perceived value of that object. A real world example of this would be an individual refusing to part with an old painting for any price due to it having "sentimental value". Work by Morewedge, Shu, Gilbert and Wilson (2009)[15] provides some support for these theories, as does work by Maddux et al. (2010).[16] Others have argued that the short duration of ownership or highly prosaic items typically used in endowment effect type studies is not sufficient to produce such a connection, conducting research demonstrating support for those points (e.g. Liersch & Rottenstreich, Working Paper).

Evolutionary arguments

Huck, Kirchsteiger & Oechssler (2005)[17] have raised the hypothesis that natural selection may favor individuals whose preferences embody an endowment effect given that it may improve one's bargaining position in bilateral trades. Thus in a small tribal society with a few alternative sellers (i.e. where the buyer may not have the option of moving to an alternative seller), having a predisposition towards embodying the endowment effect may be evolutionarily beneficial. This may be linked with findings (Shogren, et al., 1994[14]) that suggest the endowment effect is less strong when the relatively artificial sense of scarcity induced in experimental settings is lessened.

Criticisms

Some economists have questioned the effect's existence. Hanemann (1991)[13] noted that economic theory only suggests that WTP and WTA should be equal for goods which are close substitutes, so observed differences in these measures for goods such as environmental resources and personal health can be explained without reference to an endowment effect. Shogren, et al. (1994)[14] noted that the experimental technique used by Kahneman and Thaler (1990)[12] to demonstrate the endowment effect created a situation of artificial scarcity. They performed a more robust experiment with the same goods used by Kahneman and Thaler[12] (chocolate bars and mugs) and found little evidence of the endowment effect. Others have argued that the use of hypothetical questions and experiments involving small amounts of money tells us little about actual behavior (e.g. Hoffman and Spitzer, 1993, p. 69, n. 23[5] ) with some research supporting these points (e.g. Kahneman, Knetsch and Thaler, 1990,[2] Harless, 1989[18]) and others not (e.g. Knez, Smith and Williams, 1985)[19]

Implications

Herbert Hovenkamp (1991)[20] has argued that the presence of an endowment effect has significant implications for law and economics, particularly in regard to welfare economics. He argues that the presence of an endowment effect indicates that a person has no indifference curve (see however Hanemann, 1991[13]) rendering the neoclassical tools of welfare analysis useless, concluding that courts should instead use WTA as a measure of value. Fischler (1995)[21] however, raises the counterpoint that using WTA as a measure of value would deter the development of a nation's infrastructure and economic growth.

The endowment effect has also been raised as a possible explanation for the lack of demand for reverse mortgage opportunities in the United States (contracts in which a home owner sells back his property to the bank in exchange for an annuity) (Huck, Kirchsteiger & Oechssler, 2005).[17]

See also

References

- ↑ J.E. Roeckelein (19 January 2006). Elsevier's Dictionary of Psychological Theories. Elsevier. p. 147. ISBN 978-0-08-046064-2. Retrieved 6 September 2013.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Kahneman, D., Knetsch, J. L., & Thaler, R. H. (2009). Experimental Tests of the Endowment Effect and the Coase Theorem. In E. L. Khalil (Ed.) , The New Behavioral Economics. Volume 3. Tastes for Endowment, Identity and the Emotions (pp. 119-142). Elgar Reference Collection. International Library of Critical Writings in Economics, vol. 238. Cheltenham, U.K. and Northampton, Mass.: Elgar.

- ↑ Ziv Carmon and Dan Ariely (2000) 'Focusing on the Forgone: How Value Can Appear So Different to Buyers and Sellers' Journal of Consumer Research. 27(3), 360-370.

- ↑ Carrots dressed as sticks. (2010). Economist, 394(8665), 72.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Hoffman, Elizabeth and Spitzer, Matthew L. (1993), ‘Willingness to Pay vs. Willingness to Accept:Legal and Economic Implications’, 71 Washington University Law Quarterly, 59-114.

- ↑ Harbaugh, W. T., Krause, K., & Vesterlund, L. (2001). Are Adults Better Behaved Than Children? Age, Experience, and the Endowment Effect. Economics Letters, 70(2), 175-181.

- ↑ Kanngiesser, P., Santos, L. R., Hood, B. M., & Call, J. (2011). The limits of endowment effects in great apes (Pan paniscus, Pan troglodytes, Gorilla gorilla, Pongo pygmaeus). Journal Of Comparative Psychology, 125(4), 436-445. doi:10.1037/a0024516

- ↑ Lakshminaryanan, V., Chen, M., & Santos, L. R. (2008). Endowment effect in capuchin monkeys. Philosophical Transactions Of The Royal Society Of London B Biological Sciences, 363(1511), 3837-3844.

- ↑ Coombs, C.H., Bezembinder, T.G., & Goode, F.M. (1967).‘Testing Expectation Theories of Decision Making without Measuring Utility or Subjective Probability’, 4 Journal of Mathematical Psychology, 72-103. doi:10.1016/0022-2496(67)90042-9

- ↑ Slovic, P. and Lichtenstein, S. (1968), ‘Relative Importance of Probabilities and Payoffs in Risk Taking’,78,Journal of Experimental Psychology, 1-18.

- ↑ Thaler, R. (1980). Toward a positive theory of consumer choice. Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 1, 39-60.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Kahneman, Daniel and Tversky, Amos (1979), ‘Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision Under Risk’, 47 Econometrica, 263-291.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 W. Michael Hanemann 'Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept: How Much Can They Differ?' The American Economic Review, Vol. 81, No. 3. (Jun., 1991), pp. 635–647

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Jason F. Shogren; Seung Y. Shin; Dermot J. Hayes; James B. Kliebenstein 'Resolving Differences in Willingness to Pay and Willingness to Accept' The American Economic Review, Vol. 84, No. 1. (Mar., 1994), pp. 255–270.

- ↑ Morewedge, C., Shu, L., Gilbert, D, & Wilson, T. (2009). Bad riddance or good rubbish? Ownership and not loss aversion causes the endowment effect. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 45, 947-951.

- ↑ Maddux, William W., Yang, Haiyang, Falk, Carl, Adam, Hajo, Adair, Wendy, Endo, Yumi., Carmon, Ziv, & Heine, Steve J. (2010). For whom is parting with possessions more painful? Cultural differences in the endowment effect. Psychological Science, 21(12) 1910–1917.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Huck, S., Kirchsteiger, G., & Oechssler, J. (2005). Learning to like what you have – explaining the endowment effect. Economic Journal, 115(505), 689-702. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2005.01015.x

- ↑ Harless, David W. (1989), ‘More Laboratory Evidence on the Disparity Between Willingness to Pay and Compensation Demanded’, 11 Journal of Economic Behavior and Organization, 359-379.

- ↑ Knez, P., Smith, V. L. & Williams, A. W. (1985), ‘Individual Rationality, Market Rationality and Value Estimation’, 75, American Economic Review, 397-402.

- ↑ Hovenkamp, Herbert J. (1991), ‘Legal Policy and the Endowment Effect’, 20 Journal of Legal Studies, 225-247

- ↑ Fischel, William A. (1995), ‘The Offer/Ask Disparity and Just Compensation for Takings: A Constitutional Choice Perspective’, 15 International Review of Law and Economics, 187-203.

External links

- "The WTP-WTA Gap, the 'Endowment Effect,' Subject Misconceptions, and Experimental Procedures", Charles Plott et al., American Economic Review 2005

- The Endowment Effect's Disappearing Act, Larry E. Ribstein, December 4, 2005

- "Exchange Asymmetries Incorrectly Interpreted as Evidence of Endowment Effect Theory and Prospect Theory?", Charles Plott et al., American Economic Review 2007

- The "Mystery" of the Endowment Effect, Per Bylund, December 28, 2011