Endometriosis

| Endometriosis | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| |

| ICD-10 | N80 |

| ICD-9 | 617.0 |

| OMIM | 131200 |

| DiseasesDB | 4269 |

| MedlinePlus | 000915 |

| eMedicine | med/3419 ped/677 emerg/165 |

| MeSH | D004715 |

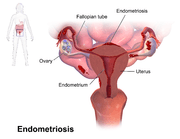

Endometriosis is a gynecological condition in which cells from the lining of the uterus (endometrium) appear and flourish outside the uterine cavity, most commonly on the membrane which lines the abdominal cavity, the peritoneum. The uterine cavity is lined with endometrial cells, which are under the influence of female hormones. Endometrial cells in areas outside the uterus are also influenced by hormonal changes and respond in a way that is similar to the cells found inside the uterus. Symptoms of endometriosis are pain and infertility. The pain often is worse with the menstrual cycle and is the most common cause of secondary dysmenorrhea. Endometriosis was first identified by Baron Carl von Rokitansky in 1860.[1]

Endometriosis is typically seen during the reproductive years; it has been estimated that endometriosis occurs in roughly 6–10% of women.[2] Symptoms may depend on the site of active endometriosis. Its main but not universal symptom is pelvic pain in various manifestations. Endometriosis is a common finding in women with infertility.[2] Endometriosis has a significant social and psychological impact.[3]

There is no cure for endometriosis, but it can be treated in a variety of ways, including pain medication, hormonal treatments, and surgery.[4]

Signs and symptoms

Pelvic pain

A major symptom of endometriosis is recurring pelvic pain. The pain can range from mild to severe cramping or stabbing pain that occurs on both sides of the pelvis, in the lower back and rectal area, and even down the legs. The amount of pain a woman feels correlates poorly with the extent or stage (1 through 4) of endometriosis, with some women having little or no pain despite having extensive endometriosis or endometriosis with scarring, while other women may have severe pain even though they have only a few small areas of endometriosis.[5] Symptoms of endometriosis-related pain may include:[6]

- dysmenorrhea – painful, sometimes disabling cramps during menses; pain may get worse over time (progressive pain), also lower back pains linked to the pelvis

- chronic pelvic pain – typically accompanied by lower back pain or abdominal pain

- dyspareunia – painful sex

- dysuria – urinary urgency, frequency, and sometimes painful voiding

Throbbing, gnawing, and dragging pain to the legs are reported more commonly by women with endometriosis.[7] Compared with women with superficial endometriosis, those with deep disease appear to be more likely to report shooting rectal pain and a sense of their insides being pulled down.[citation needed] Individual pain areas and pain intensity appears to be unrelated to the surgical diagnosis, and the area of pain unrelated to area of endometriosis.[citation needed]

Endometriosis lesions react to hormonal stimulation and may "bleed" at the time of menstruation. The blood accumulates locally, causes swelling, and triggers inflammatory responses with the activation of cytokines. This process may cause pain. Pain can also occur from adhesions (internal scar tissue) binding internal organs to each other, causing organ dislocation. Fallopian tubes, ovaries, the uterus, the bowels, and the bladder can be bound together in ways that are painful on a daily basis, not just during menstrual periods.[citation needed]

Also, endometriotic lesions can develop their own nerve supply, thereby creating a direct and two-way interaction between lesions and the central nervous system, potentially producing a variety of individual differences in pain that can, in some women, become independent of the disease itself.[5]

Infertility

Many women with infertility may have endometriosis. As endometriosis can lead to anatomical distortions and adhesions (the fibrous bands that form between tissues and organs following recovery from an injury), the causality may be easy to understand; however, the link between infertility and endometriosis remains enigmatic when the extent of endometriosis is limited.[8] It has been suggested that endometriotic lesions release factors which are detrimental to gametes or embryos, or, alternatively, endometriosis may more likely develop in women who fail to conceive for other reasons and thus be a secondary phenomenon; for this reason it is preferable to speak of endometriosis-associated infertility.[9]

Other

Other symptoms include constipation[7] and chronic fatigue.[10]

In addition to pain during menstruation, the pain of endometriosis can occur at other times of the month. There can be pain with ovulation, pain associated with adhesions, pain caused by inflammation in the pelvic cavity, pain during bowel movements and urination, during general bodily movement like exercise, pain from standing or walking, and pain with intercourse. But the most desperate pain is usually with menstruation and many women dread having their periods. Pain can also start a week before menses, during and even a week after menses, or it can be constant. There is no known cure for endometriosis.[11]

Current research has demonstrated an association between endometriosis and certain types of cancers, notably some types of ovarian cancer,[12][13] non-Hodgkin's lymphoma and brain cancer.[14] Despite similarities in their name and location, endometriosis bears no relationship to endometrial cancer.[citation needed]

Endometriosis often also coexists with leiomyoma or adenomyosis, as well as autoimmune disorders. A 1988 survey conducted in the US found significantly more hypothyroidism, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, autoimmune diseases, allergies and asthma in women with endometriosis compared to the general population.[15]

Complications

Complications of endometriosis include internal scarring, adhesions, pelvic cysts, chocolate cyst of ovaries, ruptured cysts, and bowel and ureteral obstruction resulting from pelvic adhesions.[citation needed] Infertility can be related to scar formation and anatomical distortions due to the endometriosis; however, endometriosis may also interfere in more subtle ways: cytokines and other chemical agents may be released that interfere with reproduction.[citation needed] Peritonitis from bowel perforation can occur.[citation needed]

Ovarian endometriosis may complicate pregnancy by decidualization, abscess and/or rupture.[16]

Pleural implantations are associated with recurrent right pneumothoraces at times of menses, termed catamenial pneumothorax.[citation needed]

Risk factors

Genetics

Genetic predisposition plays a role in endometriosis.[17] Daughters or sisters of patients with endometriosis are at higher risk of developing endometriosis themselves; low progesterone levels may be genetic, and may contribute to a hormone imbalance.[18] There is an about 6-fold increased incidence in women with an affected first-degree relative.[19]

It has been proposed that endometriosis results from a series of multiple hits within target genes, in a mechanism similar to the development of cancer.[17] In this case, the initial mutation may be either somatic or heritable.[17]

Individual genomic changes (found by genotyping) that have been associated with endometriosis include:

In addition, there are many findings of altered gene expression and epigenetics, but both of these can also be a secondary result of, for example, environmental factors and altered metabolism. Examples of altered gene expression include that of miRNAs.[17]

Environmental toxins

Several studies have investigated the potential link between exposure to dioxins and endometriosis, but the evidence is equivocal and potential mechanisms are poorly understood.[22] In the early 1990s, Sherry Rier and colleagues found that 79% of a group of monkeys developed endometriosis ten years after exposure to dioxin. The severity of endometriosis found in the monkeys was directly related to the amount of TCDD (2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzodioxin – the most toxic dioxin) to which they had been exposed . Monkeys that were fed dioxin in amounts as small as five parts per trillion developed endometriosis. In addition, the dioxin-exposed monkeys showed immune abnormalities similar to those observed in women with endometriosis.[23] A similar follow up study in 2000 observed similar findings.[24] In 1994, Drs. Frederick Yves Bois and Brenda Eskenazi wrote in the Environmental Health Perspectives journal titled Possible Risk of Endometriosis for Seveso, Italy Residents: An Assessment of Exposure to Dioxin stating that women who are sensitive to exposure may have a greater risk of having this condition.[25] However, a 2004 review of studies of dioxin and endometriosis concluded that "the human data supporting the dioxin-endometriosis association are scanty and conflicting,"[26] and a 2009 follow-up review also found that there was "insufficient evidence at this moment" in support of a link between dioxin exposure and women developing endometriosis.[27] A 2008 review by Rier, however, concluded that more work was needed, stating that "although preliminary work suggests a potential involvement of exposure to dioxins in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, much work remains to clearly define cause and effect and to understand the potential mechanism of toxicity."[28]

Aging

Aging brings with it many effects that may reduce fertility. Depletion over time of ovarian follicles affects menstrual regularity. Endometriosis has more time to produce scarring of the ovary and tubes so they cannot move freely or it can even replace ovarian follicular tissue if ovarian endometriosis persists and grows. Leiomyomata (fibroids) can slowly grow and start causing endometrial bleeding that disrupts implantation sites or distorts the endometrial cavity which affects carrying a pregnancy in the very early stages. Abdominal adhesions from other intraabdominal surgery, or ruptured ovarian cysts can also affect tubal motility needed to sweep the ovary and gather an ovulated follicle (egg).

Incidences of endometriosis have occurred in postmenopausal women,[29] and in less common cases, girls may have endometriosis symptoms before they even reach menarche.[30][31]

Pathophysiology

While the exact cause of endometriosis remains unknown, many theories have been presented to better understand and explain its development. These concepts do not necessarily exclude each other. The pathophysiology of endometriosis is likely to be multifactorial and to involve an interplay between several factors.[17]

Broadly, the aspects of the pathophysiology can basically be classified as underlying predisposing factors, inflammation, metabolic changes, formation of ectopic endometrium, and generation of pain and other effects. It is not certain, however, to what degree predisposing factors lead to metabolic and inflammatory changes and so on, or if metabolic and inflammatory changes or formation of ectopic endometrium is the primary cause. Also, there are several theories within each category, but the uncertainty over what is a cause versus what is an effect when considered in relation to other aspects is as true for any individual entry in the pathophysiology of endometriosis.[17] Inflammation is a central part of the aetiopathology and causes pain.[32]

Also, pathogenic mechanisms appear to differ in the formation of distinct types of endometriotic lesion, such as peritoneal, ovarian and rectovaginal lesions.[17]

Formation

The main theories for the formation of ectopic endometrium are retrograde menstruation, müllerianosis, coelomic metaplasia and transplantation, each further described below.

Retrograde menstruation

The theory of retrograde menstruation (also called the implantation theory or transplantation theory)[33] is the most widely accepted theory for the formation of ectopic endometrium in endometriosis.[17] It suggests that during a woman's menstrual flow, some of the endometrial debris exits the uterus through the fallopian tubes and attaches itself to the peritoneal surface (the lining of the abdominal cavity) where it can proceed to invade the tissue as endometriosis.[17]

While most women may have some retrograde menstrual flow, typically their immune system is able to clear the debris and prevent implantation and growth of cells from this occurrence. However, in some patients, endometrial tissue transplanted by retrograde menstruation may be able to implant and establish itself as endometriosis. Factors that might cause the tissue to grow in some women but not in others need to be studied, and some of the possible causes below may provide some explanation, e.g., hereditary factors, toxins, or a compromised immune system. It can be argued that the uninterrupted occurrence of regular menstruation month after month for decades is a modern phenomenon, as in the past women had more frequent menstrual rest due to pregnancy and lactation.

Retrograde menstruation alone is not able to explain all instances of endometriosis, and it needs additional factors such as genetic or immune differences to account for the fact that many women with retrograde menstruation do not have endometriosis. Research is focusing on the possibility that the immune system may not be able to cope with the cyclic onslaught of retrograde menstrual fluid. In this context there is interest in studying the relationship of endometriosis to autoimmune disease, allergic reactions, and the impact of toxins.[34][35] It is still unclear what, if any, causal relationship exists between toxins, autoimmune disease, and endometriosis. There are immune system changes in women with endometriosis, such as an increase macrophage-derived secretion products, but it is unknown if these are contributing to the disorder or are reactions from it.[36]

In addition, at least one study found that endometriotic lesions are biochemically very different from artificially transplanted ectopic tissue.[37] The latter finding, however, can in turn be explained by that the cells that establish endometrial lesions are not of the main cell type in ordinary endometrium, but rather of a side population cell type, as supported by exhibitition of a side population phenotype upon staining with Hoechst dye and by flow cytometric analysis.[17] Similarly, there are changes in for example the mesothelium of the peritoneum in women with endometriosis, such as loss of tight junctions, but it is unknown if these are causes or effects of the disorder.[36]

In rare cases where imperforate hymen does not resolve itself prior to the first menstrual cycle and goes undetected, blood and endometrium are trapped within the uterus of the patient until such time as the problem is resolved by surgical incision. Many health care practitioners never encounter this defect, and due to the flu-like symptoms it is often misdiagnosed or overlooked until multiple menstrual cycles have passed. By the time a correct diagnosis has been made, endometrium and other fluids have filled the uterus and fallopian tubes with results similar to retrograde menstruation resulting in endometriosis. The initial stage of endometriosis may vary based on the time elapsed between onset and surgical procedure.

The theory of retrograde menstruation as a cause of endometriosis was first proposed by John A. Sampson.

Other theories

- Müllerianosis: A competing theory states that cells with the potential to become endometrial are laid down in tracts during embryonic development and organogenesis. These tracts follow the female reproductive (Mullerian) tract as it migrates caudally (downward) at 8–10 weeks of embryonic life. Primitive endometrial cells become dislocated from the migrating uterus and act like seeds or stem cells. This theory is supported by foetal autopsy.[38]

- Coelomic metaplasia: This theory is based on the fact that coelomic epithelium is the common ancestor of endometrial and peritoneal cells and hypothesizes that later metaplasia (transformation) from one type of cell to the other is possible, perhaps triggered by inflammation.[39]

- Vasculogenesis: Up to 37% of the microvascular endothelium of ectopic endometrial tissue originates from endothelial progenitor cells, which result in de novo formation of microvessels by the process of vasculogenesis rather than the conventional process of angiogenesis.[40]

Localization

Most endometriosis is found on these structures in the pelvic cavity:[citation needed]

- Ovaries (the most common site)

- Fallopian tubes

- The back of the uterus and the posterior cul-de-sac

- The front of the uterus and the anterior cul-de-sac

- Uterine ligaments such as the broad or round ligament of the uterus

- Pelvic and back wall

- Intestines, most commonly the rectosigmoid

- Urinary bladder and ureters

Bowel endometriosis affects approximately 10% of women with endometriosis, and can cause severe pain with bowel movements.[citation needed]

Endometriosis may spread to the cervix and vagina or to sites of a surgical abdominal incision.[citation needed]

Endometriosis may also present with skin lesions in cutaneous endometriosis.

Less commonly lesions can be found on the diaphragm. Diaphragmatic endometriosis is rare, almost always on the right hemidiaphragm, and may inflict cyclic pain of the right shoulder just before and during menses. Rarely, endometriosis can be extraperitoneal and is found in the lungs and CNS.[41]

Diagnosis

A health history and a physical examination can in many patients lead the physician to suspect endometriosis. Laparoscopy, a surgical procedure where a camera is used to look inside the abdominal cavity, is the gold standard in diagnosis as it permits lesion visualization, unless the lesion is visible externally, e.g. an endometriotic nodule in the vagina.

Use of pelvic ultrasound may identify large endometriotic cysts (such as endometrioma). However, endometriosis implants cannot be visualized with ultrasound technique.

The only way to diagnose endometriosis is by laparoscopy or other types of surgery with lesion biopsy.[citation needed] The diagnosis is based on the characteristic appearance of the disease, and should be corroborated by a biopsy. Surgery for diagnoses also allows for surgical treatment of endometriosis at the same time.

Although doctors can often feel the endometrial growths during a pelvic exam, and these symptoms may be signs of endometriosis, diagnosis cannot be confirmed by exam only. To the eye, lesions can appear dark blue, powder-burn black, red, white, yellow, brown or non-pigmented. Lesions vary in size. Some within the pelvis walls may not be visible, as normal-appearing peritoneum of infertile women reveals endometriosis on biopsy in 6–13% of cases.[42] Early endometriosis typically occurs on the surfaces of organs in the pelvic and intra-abdominal areas. Health care providers may call areas of endometriosis by different names, such as implants, lesions, or nodules. Larger lesions may be seen within the ovaries as ovarian endometriomas or "chocolate cysts", "chocolate" because they contain a thick brownish fluid, mostly old blood.

Frequently during diagnostic laparoscopy no lesions are found in patients with chronic pelvic pain, a symptom common to other disorders. In order to avoid invasive diagnosis and potentially life-threatening complications of laparoscopy, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the use of intramuscular injection of Lupron (3.75 mg each month) as the effective diagnostic method.[citation needed] If the chronic pelvic pain was apparently reduced or relieved with Lupron, the diagnosis is established. Note that Lupron is not approved by FDA for the treatment of endometriosis due to its long term side effects (bone loss, menopausal symptoms, low estrogen state, etc.) Most gynecologists in USA will not give Lupron as the diagnostic method for more than three months. Indeed, this approach may delay diagnosis and surgery may in any case be necessary to excise lesions.

Staging

Surgically, endometriosis can be staged I–IV (Revised Classification of the American Society of Reproductive Medicine).[43] The process is a complex point system that assesses lesions and adhesions in the pelvic organs, but it is important to note staging assesses physical disease only, not the level of pain or infertility. A patient with Stage I endometriosis may have little disease and severe pain, while a patient with Stage IV endometriosis may have severe disease and no pain or vice versa. In principle the various stages show these findings:

- Stage I (Minimal)

- Findings restricted to only superficial lesions and possibly a few filmy adhesions

- Stage II (Mild)

- In addition, some deep lesions are present in the cul-de-sac

- Stage III (Moderate)

- As above, plus presence of endometriomas on the ovary and more adhesions.

- Stage IV (Severe)

- As above, plus large endometriomas, extensive adhesions.

Endometrioma on the ovary of any significant size (Approx. 2 cm +) must be removed surgically because hormonal treatment alone will not remove the full endometrioma cyst, which can progress to acute pain from the rupturing of the cyst and internal bleeding. Endometrioma is sometimes misdiagnosed as ovarian cysts.

Markers

An area of research is the search for endometriosis markers.[44]

A systematic review in 2010 of essentially all proposed biomarkers for endometriosis in serum, plasma and urine came to the conclusion that none of them have been clearly shown to be of clinical use, although some appear to be promising.[44] Another review in 2011 identified several putative biomarkers upon biopsy, including findings of small sensory nerve fibers or defectively expressed β3 integrin subunit.[45]

The one biomarker that has been used in clinical practice over the last 20 years is CA-125.[44] However, its performance in diagnosing endometriosis is low, even though it shows some promise in detecting more severe disease.[44] CA-125 levels appear to fall during endometriosis treatment, but has not shown a correlation with disease response.[44]

It has been postulated a future diagnostic tool for endometriosis will consist of a panel of several specific and sensitive biomarkers, including both substance concentrations and genetic predisposition.[44]

Histopathology

Typical endometriotic lesions show histopathologic features similar to endometrium, namely endometrial stroma, endometrial epithelium, and glands that respond to hormonal stimuli. Older lesions may display no glands but hemosiderindeposits (see photomicrograph on right) as residual.

Immunohistochemistry has been found to be useful in diagnosing endometriosis as stromal cells have a peculiar surface antigen, CD10, thus allowing the pathologist go straight to a staining area and hence confirm the presence of stromal cells and sometimes glandular tissue is thus identified that was missed on routine H&E staining.[46]

Prevention

Limited evidence indicates that the use of combined oral contraceptives is associated with a reduced risk of endometriosis.[47]

Management

While there is no cure for endometriosis, there are two types of interventions; treatment of pain and treatment of infertility.[48] In many women menopause (natural or surgical) will abate the process.[49] In patients in the reproductive years, endometriosis is merely managed: the goal is to provide pain relief, to restrict progression of the process, and to restore or preserve fertility where needed. In younger women with unfulfilled reproductive potential, surgical treatment attempts to remove endometrial tissue and preserving the ovaries without damaging normal tissue.[50]

In general, the diagnosis of endometriosis is confirmed during surgery, at which time ablative steps can be taken. Further steps depend on circumstances: patients without infertility can be managed with hormonal medication that suppress the natural cycle and pain medication, while infertile patients may be treated expectantly after surgery, with fertility medication, or with IVF. As to the surgical procedure, ablation (or fulguration) of endometriosis (burning and vaporizing the lesions with a pointy electric device) has shown high rate of short-term recurrence after the procedure. The best surgical procedure with much less rate of short-term recurrence is to excise (cut and remove) the lesions completely.

Surgery

Conservative treatment consists of the excision (called cystectomy) of the endometrium, adhesions, resection of endometriomas, and restoration of normal pelvic anatomy as much as is possible.[8] Laparoscopy, besides being used for diagnosis, can also be used to perform surgery. It's considered a "minimally invasive" surgery because the surgeon makes very small openings (incisions) at (or around) the belly button and lower portion of the belly. A thin telescope-like instrument (the laparoscope) is placed into one incision, which allows the doctor to look for endometriosis using a small camera attached to the laparoscope. Small instruments are inserted through the incisions to remove the endometriosis tissue and adhesions. Because the incisions are very small, there will only be small scars on the skin after the procedure, and all endometriosis can be removed, and patients recover from surgery quicker and have a lower risk of adhesions.[51] 55% to 100% of women develop adhesions following pelvic surgery,[52] which can result in infertility, chronic abdominal and pelvic pain, and difficult reoperative surgery.[52]

Conservative treatment involves excision of endometriosis whilst preserving the ovaries and uterus, very important for women wishing to conceive, but may increase the risk of recurrence.[53]

Endometriosis recurrence following conservative surgery is estimated as 21.5% at 2 years and 40-50% at 5 years.[54]

A hysterectomy (removal of the uterus) can be used to treat endometriosis in patients who do not wish to conceive, however this should only be done when combined with removal of the endometriosis by excision, as if endometriosis is not also removed at the time of hysterectomy, pain may still persist.[55]

For patients with extreme pain, a presacral neurectomy may be very rarely performed where the nerves to the uterus are cut. However, this technique is very rarely used due to the high incidence of associated complications including including presacral haematoma and irreversible problems with urination and constipation.[55]

Hormones

- Progesterone or Progestins: Progesterone counteracts estrogen and inhibits the growth of the endometrium. Such therapy can reduce or eliminate menstruation in a controlled and reversible fashion. Progestins are chemical variants of natural progesterone. An example of a Progestin is Dienogest (Visanne).

- Avoiding products with xenoestrogens, which have a similar effect to naturally produced estrogen and can increase growth of the endometrium.

- Hormone contraception therapy: Oral contraceptives reduce the menstrual pain associated with endometriosis.[56] They may function by reducing or eliminating menstrual flow and providing estrogen support. Typically, it is a long-term approach. Recently Seasonale was FDA approved to reduce periods to 4 per year. Other OCPs have however been used like this off label for years. Continuous hormonal contraception consists of the use of combined oral contraceptive pills without the use of placebo pills, or the use of NuvaRing or the contraceptive patch without the break week. This eliminates monthly bleeding episodes.

- Danazol (Danocrine) and gestrinone are suppressive steroids with some androgenic activity.[50] Both agents inhibit the growth of endometriosis but their use remains limited as they may cause hirsutism and voice changes.

- Gonadotropin Releasing Hormone (GnRH) agonist:[50] These agents work by increasing the levels of GnRH. Consistent stimulation of the GnRH receptors results in downregulation, inducing a profound hypoestrogenism by decreasing FSH and LH levels. While effective in some patients, they induce unpleasant menopausal symptoms, and over time may lead to osteoporosis. To counteract such side effects some estrogen may have to be given back (add-back therapy). These drugs can only be used for six months at a time.

- Lupron depo shot is a GnRH agonist and is used to lower the hormone levels in the woman's body to prevent or reduce growth of endometriosis. The injection is given in 2 different doses: a 3-month-dose injections (11.25 mg); or a 6 month course of monthly injections, each with the dosage of 3.75 mg.[57] Note that the symptoms will mostly come back after completing the Lupron courses. Long-term use of Lupron (over 5–6 months) is associated with severe side effects, and should not be offered to the patients. Thus, Lupron is not considered a treatment option for endometriosis. Instead, it is widely used in the United States as the non-invasive method for the diagnosis of endometriosis.

- Aromatase inhibitors are medications that block the formation of estrogen and have become of interest for researchers who are treating endometriosis.[58]

Other medication

- NSAIDs: Anti-inflammatory. They are commonly used in conjunction with other therapy. For more severe cases narcotic prescription drugs may be used. NSAID injections can be helpful for severe pain or if stomach pain prevents oral NSAID use.

- Opioids: Morphine sulphate tablets and other opioid painkillers work by mimicking the action of naturally occurring pain-reducing chemicals called "endorphins". There are different long acting and short acting medications that can be used alone or in combination to provide appropriate pain control.

- Following laparoscopic surgery women who were given Chinese herbs were reported to have comparable benefits to women with conventional drug treatments, though the journal article that reviewed this study also noted that "the two trials included in this review are of poor methodological quality so these findings must be interpreted cautiously. Better quality randomised controlled trials are needed to investigate a possible role for CHM [Chinese Herbal Medicine] in the treatment of endometriosis.",[59]

- Pentoxifylline, an immunomodulating agent, has been theorized to improve pain as well as improve pregnancy rates in women with endometriosis. Upon systematic review, The Cochrane Collaboration examined three randomized controlled trials (RCT) in which pregnancy rates were examined and one RCT in which pain improvement was studied. The Systematic Review included 334 participants. Upon systematic review of 3 Randomized control trials, there is no statistically significance difference in clinical pregnancy rates between women treated with pentoxifylline and those not treated with pentoxifylline (OR 1.54, 95% CI: 0.89-2.66). Upon review of reduction in pain, a decrease in pain was found with pentoxifylline treatment, however it was not statistically significant (OR -1.6 95% CI: -3.32-0.12). The Cochrane Review ultimately concludes that there is too little evidence to support the use of pentoxifylline in the management of endometriosis with regards to improved fertility or reduction in pain.[60] Current American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) guidelines do not include immune-modulators, such as pentoxifylline, in standard treatment protocols.[61]

- Angiogenesis inhibitors lack clinical evidence of efficacy in endometriosis therapy.[62] Under experimental in vitro and in vivo conditions, compounds that have been shown to exert inhibitory effects on endometriotic lesions include growth factor inhibitors, endogenous angiogenesis inhibitors, fumagillin analogues, statins, cyclo-oxygenase-2 inhibitors, phytochemical compounds, immunomodulators, dopamine agonists, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor agonists, progestins, danazol and gonadotropin-releasing hormone agonists.[62] However, many of these agents are associated with undesirable side effects and more research is necessary. An ideal therapy would diminish inflammation and underlying symptoms without being contraceptive.[63][64]

Manual physical therapy

Manual therapy has been shown to play a role in multidisciplinary approaches to the treatment of sexual dysfunction associated with endometriosis.[65] The overall effectiveness of manual physical therapy to treat endometriosis has not yet been identified.[66]

Nutritional therapy

Nutritional therapy has been shown to play a role and aid in many of the symptoms of endometriosis.[67] Research in Italy has also shown that removal of gluten from the diet can ease the pain of 75% of the women with endometriosis.[68]

Comparison of interventions

Efficacy studies show that both medicinal and surgical interventions produce roughly equivalent pain-relief benefits. Recurrence of pain was found to be 44 and 53 percent with medicinal and surgical interventions, respectively.[18] Each approach has advantages and disadvantages.[39] Manual therapy showed a decrease in pain for 84 percent of study participants, and a 93 percent improvement in sexual function.[69]

The advantages of medicinal intervention are decreased initial cost, therapy can be modified as needed, and effective pain control.[citation needed] Its disadvantages are common adverse effects, unlikely improvement in fertility, and limitations on the length of time some can be used.[citation needed] Evidence on how effective medication is for relieving pain associated with endometriosis is limited.[48]

The advantages of surgery are demonstrated efficacy for pain control,[70] it is more effective for infertility than medicinal intervention,[50] it provides a definitive diagnosis,[50] and surgery can often be performed as a minimally invasive (laparoscopic) procedure to reduce morbidity and minimize the risk of post-operative adhesions.[71] Efforts to develop effective strategies to reduce or prevent adhesions have been undertaken, but their formation remain a frequent side effect of abdominal surgery.[52]

The advantages of physical therapy techniques are decreased cost, absence of major side-effects, it does not interfere with fertility, and near-universal increase of sexual function.[69] Disadvantages are that there are no large or long-term studies of its use for treating pain or infertility related to endometriosis.[69]

Treatment of infertility

While roughly similar to medicinal interventions in treating pain, the efficacy of surgery is especially significant in treating infertility. One study has shown that surgical treatment of endometriosis approximately doubles the fecundity (pregnancy rate).[72] The use of medical suppression after surgery for minimal/mild endometriosis has not shown benefits for patients with infertility.[9] Use of fertility medication that stimulates ovulation (clomiphene citrate, gonadotropins) combined with intrauterine insemination (IUI) enhances fertility in these patients.[9]

In-vitro fertilization (IVF) procedures are effective in improving fertility in many women with endometriosis. IVF makes it possible to combine sperm and eggs in a laboratory and then place the resulting embryos into the woman's uterus. The decision when to apply IVF in endometriosis-associated infertility cases takes into account the age of the patient, the severity of the endometriosis, the presence of other infertility factors, and the results and duration of past treatments. In ovarian hyperstimulation as part of IVF in women with endometriosis, using a standard GnRH agonist protocol has been found to be equally effective in regard to using a GnRH antagonist protocol in terms of pregnancy rate.[73] On the other hand, when using a GnRH agonist protocol, long-term (three to six months) pituitary down-regulation before IVF for women with endometriosis has been estimated to increase the odds of clinical pregnancy by fourfold.[73]

No difference has been found between surgery (cystectomy or aspiration) versus expectant management, or between ablation versus cystectomy, prior to IVF in women with eendometriosis.[73]

Prognosis

Proper counseling of patients with endometriosis requires attention to several aspects of the disorder. Of primary importance is the initial operative staging of the disease to obtain adequate information on which to base future decisions about therapy. The patient's symptoms and desire for childbearing dictate appropriate therapy. Not all therapy works for all patients. Some patients have recurrences after surgery or pseudo-menopause. In most cases, treatment will give patients significant relief from pelvic pain and assist them in achieving pregnancy.[74]

The underlying process that causes endometriosis may not cease after surgical or medical intervention. Studies have shown that endometriosis recurs at a rate of 20 to 40 percent within five years following conservative surgery,[75] unless hysterectomy is performed or menopause reached. Monitoring of patients consists of periodic clinical examinations and sonography.

Vaginal childbirth decreases recurrence of endometriosis. In contrast, endometriosis recurrence rates have been shown to be higher in women who have not given birth vaginally, such as in Cesarean section.[76]

Epidemiology

Endometriosis can affect any female, from premenarche to postmenopause, regardless of race or ethnicity or whether or not they have had children. It is primarily a disease of the reproductive years.[77] Its prevalence varies, but 6–10% is a reasonable number, more common in women with infertility and chronic pelvic pain (35–50%).[2]

As an estrogen-dependent process, it can persist beyond menopause and persists in up to 40% of patients following hysterectomy.[78]

References

- ↑ Batt, Ronald E. (2011). A history of endometriosis. London: Springer. pp. 13–38. ISBN 978-0-85729-585-9.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Bulletti C, Coccia ME, Battistoni S, Borini A (August 2010). "Endometriosis and infertility". J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 27 (8): 441–7. doi:10.1007/s10815-010-9436-1. PMC 2941592. PMID 20574791.

- ↑ Culley, L.; Law, C.; Hudson, N.; Denny, E.; Mitchell, H.; Baumgarten, M.; Raine-Fenning, N. (2013). "The social and psychological impact of endometriosis on women's lives: A critical narrative review". Human Reproduction Update 19 (6): 625–639. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt027. PMID 23884896.

- ↑ "Endometriosis fact sheet". NIH. Retrieved Feb 12, 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Stratton P, Berkley KJ (2011). "Chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis: translational evidence of the relationship and implications". Hum. Reprod. Update 17 (3): 327–46. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq050. PMID 21106492.

- ↑ Endometriosis;NIH Pub. No. 02-2413; September 2002

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Ballard K, Lane H, Hudelist G, Banerjee S, Wright J (June 2010). "Can specific pain symptoms help in the diagnosis of endometriosis? A cohort study of women with chronic pelvic pain". Fertil. Steril. 94 (1): 20–7. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.01.164. PMID 19342028.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Speroff L, Glass RH, Kase NG (1999). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility (6th ed.). Lippincott Willimas Wilkins. p. 1057. ISBN 0-683-30379-1.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Buyalos RP, Agarwal SK (October 2000). "Endometriosis-associated infertility". Current Opinion in Obstetrics and Gynecology 12 (5): 377–81. doi:10.1097/00001703-200010000-00006. PMID 11111879.

- ↑ Women with Endometriosis Have Higher Rates of Some Diseases; NIH News Release; 26 September 2002; http://www.nih.gov/news/pr/sep2002/nichd-26.htm

- ↑ Colette S, Donnez J (July 2011). "Are aromatase inhibitors effective in endometriosis treatment?". Expert Opin Investig Drugs 20 (7): 917–31. doi:10.1517/13543784.2011.581226. PMID 21529311.

- ↑ Pearce, Celeste Leigh; et al. (April 2012). "Association between endometriosis and risk of histological subtypes of ovarian cancer: a pooled analysis of case—control studies". The Lancet Oncology 13 (4): 385–394. doi:10.1016/S1470-2045(11)70404-1. Retrieved Oct 8, 2012.

- ↑ Article by Prof. Farr Nezhat, MD, FACOG, FACS, University of Columbia, May 1, 2012

- ↑ Audebert A (April 2005). "La femme endométriosique est-elle différente ?" [Women with endometriosis: are they different from others?]. Gynécologie, Obstétrique & Fertilité (in French) 33 (4): 239–46. doi:10.1016/j.gyobfe.2005.03.010. PMID 15894210.

- ↑ Sinaii N, Cleary SD, Ballweg ML, Nieman LK, Stratton P (October 2002). "High rates of autoimmune and endocrine disorders, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome and atopic diseases among women with endometriosis: a survey analysis". Human Reproduction 17 (10): 2715–24. doi:10.1093/humrep/17.10.2715. PMID 12351553.

- ↑ Ueda Y, Enomoto T, Miyatake T, et al. (June 2010). "A retrospective analysis of ovarian endometriosis during pregnancy". Fertil. Steril. 94 (1): 78–84. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.02.092. PMID 19356751.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 17.4 17.5 17.6 17.7 17.8 17.9 Fauser BC, Diedrich K, Bouchard P, et al. (2011). "Contemporary genetic technologies and female reproduction". Hum. Reprod. Update 17 (6): 829–47. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr033. PMC 3191938. PMID 21896560.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Kapoor D, Davila W (2005). Endometriosis, eMedicine.

- ↑ Giudice, LC; Kao, LC (2004 Nov 13-19). "Endometriosis.". Lancet 364 (9447): 1789–99. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17403-5. PMID 15541453.

- ↑ Treloar SA, Wicks J, Nyholt DR, et al. (September 2005). "Genomewide linkage study in 1,176 affected sister pair families identifies a significant susceptibility locus for endometriosis on chromosome 10q26". American Journal of Human Genetics 77 (3): 365–76. doi:10.1086/432960. PMC 1226203. PMID 16080113.

- ↑ Painter JN et al. (2010). "Genome-wide association study identifies a locus at 7p15.2 associated with endometriosis". Nature Genetics 43 (1): 51–54. doi:10.1038/ng.731. PMC 3019124. PMID 21151130.

- ↑ Anger, D. L. (2008). "The link between environmental toxicant exposure and endometriosis". Frontiers in Bioscience 13 (13): 1578. doi:10.2741/2782.

- ↑ Sherry E. Rier, Dan C. Martin, Robert E. Bowman, W.Paul Dmowski, Jeanne L. Becker (1993). "Endometriosis in Rhesus Monkeys (Macaca mulatta) Following Chronic Exposure to 2,3,7,8-Tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin". Fundamental and Applied Toxicology 21 (4). pp. 433–441.

- ↑ Sherry E. Rier, Wayman E. Turner, Dan C. Martin, Richard Morris, George W. Lucier and George C. Clark (2001). "Serum Levels of TCDD and Dioxin-like Chemicals in Rhesus Monkeys Chronically Exposed to Dioxin: Correlation of Increased Serum PCB Levels with Endometriosis". Toxicological Sciences 51 (1). pp. 147–159. doi:10.1093/toxsci/59.1.147.

- ↑ http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1567136/pdf/envhper00393-0065.pdf

- ↑ Guo, S. W. (2004). "The Link between Exposure to Dioxin and Endometriosis: A Critical Reappraisal of Primate Data". Gynecologic and Obstetric Investigation 57 (3): 157–173. doi:10.1159/000076374. PMID 14739528.

- ↑ Guo, S. -W.; Simsa, P.; Kyama, C. M.; Mihalyi, A.; Fulop, V.; Othman, E. -E. R.; d'Hooghe, T. M. (2009). "Reassessing the evidence for the link between dioxin and endometriosis: From molecular biology to clinical epidemiology". Molecular Human Reproduction 15 (10): 609–624. doi:10.1093/molehr/gap075. PMID 19744969.

- ↑ Rier, S.; Foster, W. G. (2002). "Environmental Dioxins and Endometriosis". Toxicological Sciences 70 (2): 161–170. doi:10.1093/toxsci/70.2.161. PMID 12441361.

- ↑ Bulun SE, Zeitoun K, Sasano H, Simpson ER (1999). "Aromatase in aging women". Seminars in Reproductive Endocrinology 17 (4): 349–58. doi:10.1055/s-2007-1016244. PMID 10851574.

- ↑ Batt RE, Mitwally MF (December 2003). "Endometriosis from thelarche to midteens: pathogenesis and prognosis, prevention and pedagogy". Journal of Pediatric and Adolescent Gynecology 16 (6): 337–47. doi:10.1016/j.jpag.2003.09.008. PMID 14642954.

- ↑ Marsh EE, Laufer MR (March 2005). "Endometriosis in premenarcheal girls who do not have an associated obstructive anomaly". Fertility and Sterility 83 (3): 758–60. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2004.08.025. PMID 15749511.

- ↑ Pathogenesis and pathophysiology of endometriosis.Burney RO, Giudice LC" Fertil Steril 2012 Sep;98(3) 511-9. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2012.06.029

- ↑ Van Der Linden, P. J. (1996). "Theories on the pathogenesis of endometriosis". Human reproduction (Oxford, England). 11 Suppl 3: 53–65. PMID 9147102.

- ↑ Gleicher N, el-Roeiy A, Confino E, Friberg J (July 1987). "Is endometriosis an autoimmune disease?". Obstet Gynecol 70 (1): 115–22. PMID 3110710.

- ↑ Capellino S, Montagna P, Villaggio B, et al. (June 2006). "Role of estrogens in inflammatory response: expression of estrogen receptors in peritoneal fluid macrophages from endometriosis". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1069: 263–7. doi:10.1196/annals.1351.024. PMID 16855153.

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 Young, V. J.; Brown, J. K.; Saunders, P. T. K.; Horne, A. W. (2013). "The role of the peritoneum in the pathogenesis of endometriosis". Human Reproduction Update 19 (5): 558–569. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmt024. PMID 23720497.

- ↑ Redwine DB (October 2002). "Was Sampson wrong?". Fertility and Sterility 78 (4): 686–93. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(02)03329-0. PMID 12372441.

- ↑ Signorile PG, Baldi F, Bussani R, D'Armiento M, De Falco M, Baldi A (April 2009). "Ectopic endometrium in human foetuses is a common event and sustains the theory of müllerianosis in the pathogenesis of endometriosis, a disease that predisposes to cancer". Journal of Experimental & Clinical Cancer Research 28: 49. doi:10.1186/1756-9966-28-49. PMC 2671494. PMID 19358700.

- ↑ 39.0 39.1 "Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis". American Academy of Family Physicians. 1999-10-15. Retrieved 2011-07-26.

- ↑ Laschke MW, Giebels C, Menger MD (2011). "Vasculogenesis: a new piece of the endometriosis puzzle". Hum. Reprod. Update 17 (5): 628–36. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr023. PMID 21586449.

- ↑ Shawn Daly, MD, Consulting Staff, Catalina Radiology, Tucson, Arizona (October 18, 2004). "Endometrioma/Endometriosis". WebMD. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ↑ Nisolle M, Paindaveine B, Bourdon A, Berlière M, Casanas-Roux F, Donnez J (June 1990). "Histologic study of peritoneal endometriosis in infertile women". Fertility and Sterility 53 (6): 984–8. PMID 2351237.

- ↑ American Society For Reproductive M, (May 1997). "Revised American Society for Reproductive Medicine classification of endometriosis: 1996". Fertility and Sterility 67 (5): 817–21. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(97)81391-X. PMID 9130884.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 44.3 44.4 44.5 May KE, Conduit-Hulbert SA, Villar J, Kirtley S, Kennedy SH, Becker CM (2010). "Peripheral biomarkers of endometriosis: a systematic review". Hum. Reprod. Update 16 (6): 651–74. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq009. PMC 2953938. PMID 20462942.

- ↑ May KE, Villar J, Kirtley S, Kennedy SH, Becker CM (2011). "Endometrial alterations in endometriosis: a systematic review of putative biomarkers". Hum. Reprod. Update 17 (5): 637–53. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmr013. PMID 21672902.

- ↑ http://www.rfay.com.au/docs/cd10poster.pdf

- ↑ Vercellini P, Eskenazi B, Consonni D, et al. (2011). "Oral contraceptives and risk of endometriosis: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Hum. Reprod. Update 17 (2): 159–70. doi:10.1093/humupd/dmq042. PMID 20833638.

- ↑ 48.0 48.1 "What are the treatments for endometriosis". Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Moen, Mette H.; Margaret Rees, Marc Brincat, Tamer Erel, et. al. (September 2010). "Managing the menopause in women with a past history of endometriosis". Maturitas (Science Direct) 67 (1): 94–97. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2010.04.018. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 50.2 50.3 50.4 Wellbery, Caroline (15 October 1999). "Diagnosis and Treatment of Endometriosis". American Family Physician (American Family Physician): 1753–1762. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ "Endometriosis and Infertility: Can Surgery Help?". American Society for Reproductive Medicine. 2008. Retrieved 31 Oct 2010.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 Liakakos, T; N Thomakos, PM Fine, C Dervenis, RL Young (2001). "Peritoneal Adhesions: Etiology, Pathophysiology, and Clinical Significance". Dig Surgery (Pub Med) 18 (4): 260–273. doi:10.1159/000050149. PMID 11528133.

- ↑ Namnoum AB, Hickman TN, Goodman SB, Gehlbach DL, Rock JA (November 1995). "Incidence of symptom recurrence after hysterectomy for endometriosis". Fertility and Sterility 64 (5): 898–902. PMID 7589631.

- ↑ Guo SW, et al. (2009). "Recurrence of endometriosis and its control". Hum. Reprod. Update. PMID 19279046.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Johnson NP, Hummelshoj L; World Endometriosis Society Montpellier Consortium (June 2013). "Consensus on current management of endometriosis.". Human Reproduction. PMID 23528916.

- ↑ Harada T, Momoeda M, Taketani Y, Hoshiai H, Terakawa N (November 2008). "Low-dose oral contraceptive pill for dysmenorrhea associated with endometriosis: a placebo-controlled, double-blind, randomized trial". Fertility and Sterility 90 (5): 1583–8. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2007.08.051. PMID 18164001.

- ↑ "Lupron Depot 3.75 mg". Rx List. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Attar E, Bulun SE (May 2006). "Aromatase inhibitors: the next generation of therapeutics for endometriosis?". Fertility and Sterility 85 (5): 1307–18. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2005.09.064. PMID 16647373.

- ↑ Flower A, Liu JP, Chen S, Lewith G, Little P (2009). "Chinese herbal medicine for endometriosis". In Flower, Andrew. Cochrane Database Syst Rev (3): CD006568. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD006568.pub2. PMID 19588398.

- ↑ Lu, D; Song, H, Li, Y, Clarke, J, Shi, G (Jan 18, 2012). "Pentoxifylline for endometriosis.". Cochrane database of systematic reviews (Online) 1: CD007677. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007677.pub3. PMID 22258970.

- ↑ "Practice bulletin no. 114 management of endometriosis". Obstet Gynecol 116 (1): 223–36. July 2010. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181e8b073. PMID 20567196.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 53.Laschke, M. W.; Menger, M. D. (2012). "Anti-angiogenic treatment strategies for the therapy of endometriosis". Human Reproduction Update 18 (6): 682–702. doi:10.1093/humupd/dms026. PMID 22718320.

- ↑ 54. The role of Lipoxin A4 in endometriosis. Canny GO, Lessey BA. Mucosal Immunology 2013 May;6(3) 439-50. doi:10.1038/mi.2013.9

- ↑ 55. An update on the pharmacological management of endometriosis. Streuli, I, de Ziegler, D et al. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2013 Feb;14(3) 291-305. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2013.767334.

- ↑ Bronfort, Ger; Mitch Haas, Roni Evans, Brent Leininger, Jay Triano (2010). "Effectiveness of manual therapies; the UK evidence report". Chiropractic & Osteopathy (BiomedCentral) 18: 3. doi:10.1186/1746-1340-18-3. PMC 2841070. PMID 20184717. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Valiani, Mahboubeh; Niloofar Ghasemi, Parvin Bahadoran, Reza Heshmat (Autumn 2010). "The effects of massage therapy on dysmenorrheal caused by endometriosis". Iran J Nurs Midwifery (NCBI). PMC 3093183. Retrieved 20 August 2013.

- ↑ Shepperson Mills, Dian; Vernon, Michael (2002). Endometriosis a key to healing and fertility through nutrition. HarperCollinsPublishers Ltd. ISBN 978-0-00-713310-9.

- ↑ "Gluten-free diet: a new strategy for management of painful endometriosis related symptoms?". PubMed. Retrieved 2014-01-27.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Wurn, Belinda F.; Lawrence J. Wurn, Kimberly Patterson, C. Richard King, Eugenia S. Scharf (2011). "Decreasing dyspareunia and dysmenorrhea in women with endometriosis via a manual physical therapy: Results from two independent studies". Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders (Journal of Endometriosis and Pelvic Pain Disorders). doi:10.5301/JE.2012.9088. Retrieved 19 August 2013.

- ↑ Kaiser A, Kopf A, Gericke C, Bartley J, Mechsner S. (16 January 2009). "The influence of peritoneal endometriotic lesions on the generation of endometriosis-related pain and pain reduction after surgical excision". Arch Gynecol Obstet. 280 (3): 369–73. doi:10.1007/s00404-008-0921-z. PMID 19148660.

- ↑ Radosa MP, Bernardi TS, Georgiev I, Diebolder H, Camara O, Runnebaum IB (June 2010). "Coagulation versus excision of primary superficial endometriosis: a 2-year follow-up". Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 150 (2): 195–8. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2010.02.022. PMID 20303642.

- ↑ Marcoux S, Maheux R, Bérubé S (July 1997). "Laparoscopic surgery in infertile women with minimal or mild endometriosis. Canadian Collaborative Group on Endometriosis". The New England Journal of Medicine 337 (4): 217–22. doi:10.1056/NEJM199707243370401. PMID 9227926.

- ↑ 73.0 73.1 73.2 Farquhar, C.; Rishworth, J. R.; Brown, J.; Nelen, W. L. M.; Marjoribanks, J. (2013). "Assisted reproductive technology: an overview of Cochrane Reviews". In Brown, Julie. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010537.pub2.

- ↑ Sanaz Memarzadeh, MD, Kenneth N. Muse, Jr., MD, & Michael D. Fox, MD (September 21, 2006). "Endometriosis". Differential Diagnosis and Treatment of endometriosis. Armenian Health Network, Health.am. Retrieved 2006-12-19.

- ↑ "Recurrent Endometriosis: Surgical Management". Endometriosis. The Cleveland Clinic. 7 Jan 2010. Retrieved 31 Oct 2010.

- ↑ Bulletti C, Montini A, Setti PL, Palagiano A, Ubaldi F, Borini A (June 2009). "Vaginal parturition decreases recurrence of endometriosis". Fertil. Steril. 94 (3): 850–5. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.04.012. PMID 19524893.

- ↑ Nothnick WB (2011). "The emerging use of aromatase inhibitors for endometriosis treatment". Reprod. Biol. Endocrinol. 9: 87. doi:10.1186/1477-7827-9-87. PMC 3135533. PMID 21693036.

- ↑ "Endometriosis – Hysterectomy". Umm.edu. Retrieved 2009-08-19.

Further reading

- Overton, Caroline (2002). An atlas of endometriosis (2nd ed.). Boca Raton [Fla.]: Parthenon Pub. Group. ISBN 1-84214-022-1.

- Giudice, Linda C; Evers, Johannes L. H; Healy, David L, eds. (2011). Endometriosis: Science and Practice. Wiley Blackwell. doi:10.1002/9781444398519. ISBN 9781444398519.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Endometriosis. |

- Endometriosis at MedlinePlus

- Endometriosis fact sheet from womenshealth.gov

- 's_Health/Conditions_and_Diseases/Uterus/Endometriosis Endometriosis on the Open Directory Project

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||