Endometrial cancer

| Endometrial | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

Micrograph of endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma, the most common form of endometrial cancer. H&E stain. | |

| ICD-10 | C54.1 |

| ICD-9 | 182.0 |

| OMIM | 608089 |

| DiseasesDB | 4252 |

| MedlinePlus | 000910 |

| eMedicine | med/674 radio/253 |

| MeSH | D016889 |

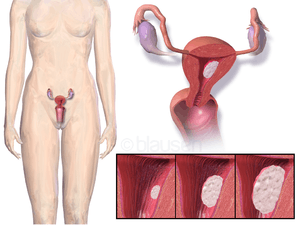

Endometrial cancer is any of several types of malignancies that arise from the endometrium, or lining, of the uterus. Endometrial cancers are the most common gynecologic cancers in developed countries,[1] with over 142,200 women diagnosed each year.[2] The incidence is on a slow rise secondary to an increasing population age and an increasing body mass index, with 39% of cases attributed to obesity.[2] The most common subtype, endometrioid adenocarcinoma, typically occurs within a few decades of menopause, is associated with obesity, excessive estrogen exposure, often develops in the setting of endometrial hyperplasia, and presents most often with vaginal bleeding. Endometrial carcinoma is the third most common cause of gynecologic cancer death (behind ovarian and cervical cancer). A total abdominal hysterectomy (surgical removal of the uterus) with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy is the most common therapeutic approach.

Endometrial cancer may sometimes be referred to as uterine cancer. However, different cancers may develop not only from the endometrium itself but also from other tissues of the uterus, including cervical cancer, sarcoma of the myometrium, and trophoblastic disease.

Classification

Carcinoma

Most endometrial cancers are carcinomas (usually adenocarcinomas), meaning that they originate from the single layer of epithelial cells that line the endometrium and form the endometrial glands. There are many microscopic subtypes of endometrial carcinoma, but they are broadly organized into two categories, type I and type II, based on clinical features and pathogenesis.[3]

The first type, type I endometrial cancers occur most commonly in pre- and peri-menopausal women, are more common in white women, often with a history of excessive thickening of the inner lining of the uterus (endometrial hyperplasia) and exposure to elevated levels of estrogen that are not counterbalanced by progesterone (unopposed estrogen exposure). Type I endometrial cancers are often low-grade, minimally invasive into the underlying uterine wall (myometrium), and are of the endometrioid type, and carry a good prognosis.[3] In endometrioid cancer, the cancer cells grow in patterns reminiscent of normal endometrium.

The second type, type II endometrial cancers usually occur in older, post-menopausal women, are more common in African-Americans, and are not associated with increased exposure to estrogen. Type II endometrial cancers are often high-grade, with deep invasion into the underlying uterine wall (myometrium), and are of the serous or clear cell type, and carry a poorer prognosis.[3]

Sarcoma

In contrast to endometrial carcinomas, the uncommon endometrial stromal sarcomas are cancers that originate in the non-glandular connective tissue of the endometrium. Uterine carcinosarcoma, formerly called Malignant mixed müllerian tumor, is a rare uterine cancer that contains cancerous cells of both glandular and sarcomatous appearance - in this case, the cell of origin is unknown.[4]

-

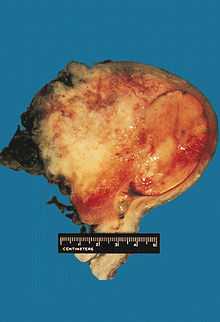

Endometrial stromal sarcoma.

-

Uterine carcinosarcoma.

-

An endometrial adenocarcinoma invading the uterine muscle.

Signs and symptoms

- Vaginal bleeding and/or spotting in postmenopausal women.

- Abnormal uterine bleeding, abnormal menstrual periods.

- Bleeding between normal periods in premenopausal women in women older than 40: extremely long, heavy, or frequent episodes of bleeding (may indicate premalignant changes).

- Anemia, caused by chronic loss of blood. (This may occur if the woman has had symptoms of prolonged or frequent abnormal menstrual bleeding.)

- Lower abdominal pain or pelvic cramping.

- Thin white or clear vaginal discharge in postmenopausal women.

- Unexplained weight gain.

- Swollen glands/lymph nodes in the neck, under chin, back of head and top of clavicles.

- Incontinence.

Risk factors

- obesity[2]

- high levels of estrogen

- endometrial hyperplasia

- Lynch syndrome

- hypertension

- polycystic ovary syndrome[5]

- nulliparity (never having carried a pregnancy)

- infertility (inability to become pregnant)

- early menarche (onset of menstruation)

- late menopause (cessation of menstruation)

- endometrial polyps or other benign growths of the uterine lining

- diabetes

- Tamoxifen

- high intake of animal fat[6]

- pelvic radiation therapy

- breast cancer

- ovarian cancer

- anovulatory cycles

- age over 35

- lack of exercise[7]

- heavy daily alcohol consumption (possibly a risk factor) [8]

Diagnosis

Clinical evaluation

Routine screening of asymptomatic women is not indicated, since the disease is highly curable in its early stages. Results from a pelvic examination are frequently normal, especially in the early stages of disease. Changes in the size, shape or consistency of the uterus and/or its surrounding, supporting structures may exist when the disease is more advanced.

- A Pap smear may be either normal or show abnormal cellular changes. A Pap smear is used to screen for cervical cancer not endometrial cancer.

- Office endometrial biopsy is the traditional diagnostic method. Both endometrial and endocervical material should be sampled.

- If endometrial biopsy does not yield sufficient diagnostic material, a dilation and curettage (D&C) is necessary for diagnosing the cancer.

- Hysteroscopy allows the direct visualization of the uterine cavity and can be used to detect the presence of lesions or tumours. It also permits the doctor to obtain cell samples with minimal damage to the endometrial lining (unlike blind D&C).

- Endometrial biopsy or aspiration may assist the diagnosis.

- Transvaginal ultrasound to evaluate the endometrial thickness in women with postmenopausal bleeding is increasingly being used to evaluate for endometrial cancer.

- Ongoing research suggests that serum p53 antibody may hold value in identifying high-risk endometrial cancer.[9]

Diagnostic test study of S-p53 Ab and agreement study for high-risk endometrial cancer Kappa: 0.70 Sensitivity (%): 64 Specificity(%): 96 PPV: 78 NPV: 92

Pathology

.jpg)

The histopathology of endometrial cancers is highly diverse. The most common finding is a well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma, which is composed of numerous, small, crowded glands with varying degrees of nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and stratification. This often appears on a background of endometrial hyperplasia. Frank adenocarcinoma may be distinguished from atypical hyperplasia by the finding of clear stromal invasion, or "back-to-back" glands which represent nondestructive replacement of the endometrial stroma by the cancer. With progression of the disease, the myometrium is infiltrated.[4] However, other subtypes of endometrial cancer exist and carry a less favorable diagnosis such as the uterine papillary serous carcinoma and the clear cell carcinoma.

Further evaluation

Patients with newly-diagnosed endometrial cancer do not routinely undergo imaging studies, such as CT scans, to evaluate for extent of disease, since this is of low yield. Preoperative evaluation should include a complete medical history and physical examination, pelvic examination and rectal examination with stool guaiac test, chest X-ray, complete blood count, and blood chemistry tests, including liver function tests. Colonoscopy is recommended if the stool is guaiac positive or the woman has symptoms, due to the etiologic factors common to both endometrial cancer and colon cancer. The tumor marker CA-125 is sometimes checked, since this can predict advanced stage disease.[10] In addition to this, both D&C and Pipelle biopsy curettage give 65-70% positive predictive value. But most important of these is hysteroscopy which gives 90-95% positive predictive value.

Staging

Endometrial carcinoma is surgically staged using the FIGO cancer staging system. The 2010 FIGO staging system is as follows:

- IA Tumor confined to the uterus,

- 1B < ½ myometrial invasion

- IC > ½ myometrial invasion

- IIA Tumor involves the endocervical glands

- 11B Tumor involves the uterus and the cervical stroma

- IIIA Tumor invades serosa or adnexa

- IIIB Vaginal and/or parametrial involvement

- IIIC1 Pelvic lymph node involvement

- IIIC2 Para-aortic lymph node involvement, with or without pelvic node involvement

- IVA Tumor invasion bladder mucosa and/or bowel mucosa

- IVB Distant metastases including abdominal metastases and/or inguinal lymph nodes

Treatment

The primary treatment is surgical. Surgical treatment should consist of, at least, cytologic sampling of the peritoneal fluid, abdominal exploration, palpation and biopsy of suspicious lymph nodes, abdominal hysterectomy, and removal of both ovaries (bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy). Lymphadenectomy, or removal of pelvic and para-aortic lymph nodes, is sometimes performed for tumors that have high risk features, such as pathologic grade 3 serous or clear-cell tumors, invasion of more than 1/2 the myometrium, or extension to the cervix or adnexa. Sometimes, removal of the omentum is also performed.

Abdominal hysterectomy is recommended over vaginal hysterectomy because it affords the opportunity to examine and obtain washings of the abdominal cavity to detect any further evidence of cancer.

Women with stage 1 disease who are at increased risk for recurrence and those with stage 2 disease are often offered surgery in combination with radiation therapy.[11] Chemotherapy may be considered in some cases, especially for those with stage 3 and 4 disease. Hormonal therapy with progestins and antiestrogens has been used for the treatment of endometrial stromal sarcomas.[12]

The antibody Herceptin, which is used to treat breast cancers that overexpress the HER2/neu protein, has been tried with some success in a phase II trial in women with uterine papillary serous carcinomas that overexpress HER2/neu.[13]

Complications of treatment

- Uterine perforation may occur during a dilatation and curettage (D&C) or an endometrial biopsy.

Prognosis

While endometrial cancers are 40% more common in Caucasian women, an African American woman who is diagnosed with uterine cancer is twice as likely to die (possibly due to the higher frequency of aggressive subtypes in that population, but more probably due to delay in the diagnosis).[citation needed] Approximately 8,200 people die annually from endometrial cancer.[citation needed]

Survival rates

The 5-year survival rates for endometrial adenocarcinoma following appropriate treatment is 80%.[1] Most women, over 75%, have FIGO stage 1 or 2, which have the best prognosis.[1][2] Below is a list of 5-year survival rates by FIGO stage:[14]

| Stage | 5 year survival rate |

|---|---|

| I-A | 90% |

| I-B | 88% |

| I-C | 75% |

| II | 69% |

| III-A | 58% |

| III-B | 50% |

| III-C | 47% |

| IV-A | 17% |

| IV-B | 15% |

Recurrence rates

Recurrence of early stage endometrial cancer ranges from 3 to 17%, depending on primary and adjuvant treatment.[1] Most recurrences (70%) occur in the first three years.[1]

Quality of life

Over 70% of endometrial cancer survivors have a co-morbidity and on average they have between 2 and 3 co-morbidities.[2] It has been shown that obesity has a negative consequence for the quality of life of endometrial cancer survivors.[2]

On average endometrial cancer survivors make more use of healthcare check ups than other people.[1][15] This seems to be related to fear for recurrence, and it has been shown that this fear does not decrease even after a period of 10 years.[1]

Studies among endometrial cancer survivors show that satisfaction with information provided about the disease and treatment increases the quality of life, lowers depression and results in less anxiety.[16] People who receive information on paper, compared to oral, indicate that they receive more information and are more satisfied about the information provided.[17] The American Institute of Medicine and the Dutch Health Council recommend the use of a Survivorship Care Plan; which is a summary of patients' course of treatment, with recommendations for subsequent surveillance, management of late effects, and strategies for health promotion.[18]

Epidemiology

Endometrial cancer is the most frequent cancer occurring in the female genital tract in the United States and many other Western countries.[1][2] It has an incidence of 15–25 per 100,000 women annually.[1] It appears most frequently between ages of 55 and 65, and uncommon below 40 years of age. There are two types of endometrial cancer, type I, which occurs in perimenopausal women with estrogen excess, and type II, which occurs in older women with endometrial atrophy.[19]

Additional images

-

Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma - intermediate magnification. H&E stain.

-

Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma - high magnification. H&E stain.

-

Endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma - very high magnification. H&E stain.

-

Uterine papillary serous carcinoma. H&E stain.

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 Nicolaije K.A. et al. Follow-up practice in endometrial cancer and the association with patient and hospital characteristics: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry, Gynecologic Oncology, 129 (2), May 2013, page 324–331, PMID 23435365.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Oldenburg C.S. et al. The relationship of body mass index with quality of life among endometrial cancer survivors: a study from the population-based PROFILES registry. Gynecologic Oncology, 129 (1), April 2013, page 216–21, PMID 23296262.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Hoffman, Barbara L. (2012). Williams Gynecology: Chapter 33, Endometrial Cancer (2nd ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill Medical. ISBN 978-0071716727.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Richard Cote, Saul Suster, Lawrence Weiss, Noel Weidner (Editor) (2002). Modern Surgical Pathology (2 Volume Set). London: W B Saunders. ISBN 0-7216-7253-1.

- ↑ J.C.E. Underwood and S.S. Cross (2009). General and Systemic pathology. London: Elsevier (Churchill Livingstone). ISBN 978-0-443-06889-8.

- ↑ Goodman, ET; et al (1997). "Diet, body size, physical activity, and the risk of endometrial cancer". Cancer Res 57 (22): 5077–85. PMID 9371506.

- ↑ Friedenreich, CM; Neilson, HK, Lynch, BM (September 2010). "State of the epidemiological evidence on physical activity and cancer prevention". European journal of cancer (Oxford, England : 1990) 46 (14): 2593–604. doi:10.1016/j.ejca.2010.07.028. PMID 20843488.

- ↑ "Thirteen studies to date have reported on the relationship between endometrial cancer and alcohol consumption. Only two of these studies have reported that endometrial cancer incidence is associated with consumption of alcohol; all the others have reported either no definite association, or an inverse association." (Six studies showed an inverse association; that is, drinking was associated with a lower risk of endometrial cancer) "…if such an inverse association exists, it appears to be more pronounced in younger, or premenopausal, women."[3] "Our results suggest that only alcohol consumption equivalent to 2 or more drinks per day increases risk of endometrial cancer in postmenopausal women."

- ↑ Yamazawa, K; Shimada, H; Hirai, M; Hirashiki, K; Ochiai, T; Ishikura, H; Shozu, M; Isaka, K (2007). "Serum p53 antibody as a diagnostic marker of high-risk endometrial cancer". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 197 (5): 505.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.04.033. PMID 17980190.

- ↑ Dotters, DJ (2000). "Preoperative CA 125 in endometrial cancer: is it useful?". American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 182 (6): 1328–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2000.106251. PMID 10871446.

- ↑ Chong, I; Hoskin, PJ (2008). "Vaginal vault brachytherapy as sole postoperative treatment for low-risk endometrial cancer". Brachytherapy 7 (2): 195–9. doi:10.1016/j.brachy.2008.01.001. PMID 18358790.

- ↑ American Cancer Society - Uterine Sarcomas - Hormonal Therapy (accessed 5-25-07)

- ↑ Santin AD, Bellone S, Roman JJ, McKenney JK, Pecorelli S. (2008). "Trastuzumab treatment in patients with advanced or recurrent endometrial carcinoma overexpressing HER2/neu". Int J Gynaecol Obstet 102 (2): 128–31. doi:10.1016/j.ijgo.2008.04.008. PMID 18555254.

- ↑ American Cancer Society (2009-10-22). "How Is Endometrial Cancer Staged?". Retrieved 2010-03-09 [Note Stage I definitions in ref differed from those used on Wiki page, so adjusted table labels from 0, IA, IB, to IA, IB, IC matching definitions used here].

- ↑ Ezendam N.P. et al. Health Care Use Among Endometrial Cancer Survivors: A Study From PROFILES, a Population-Based Survivorship Registry. International Journal of Gynecological Cancer, Epub ahead of print, July 22, 2013, PMID 23881102.

- ↑ Husson O. et al, The relation between information provision and health-related quality of life, anxiety and depression among cancer survivors: a systematic review, Ann Oncol, 22, 2011, page 761–772

- ↑ Nicolaije K.A. et al. Endometrial cancer survivors are unsatisfied with received information about diagnosis, treatment and follow-up: A study from the population-based PROFILES registry, Patient education and counseling, 88(3), Sep 2012, page 427–35, PMID 22658248

- ↑ Van de Poll-Franse L.V. et al. The impact of a cancer Survivorship Care Plan on gynecological cancer patient and health care provider reported outcomes (ROGY Care): study protocol for a pragmatic cluster randomized controlled trial. Trials, 5 (12). 2011 Dec, page 256, PMID 22141750

- ↑ Di Cristofano, Antonio; Ellenson, Lora Hedrick (February 2007). "Endometrial Carcinoma". Annual Review of Pathology: Mechanisms of Disease 2 (1): 57–85. doi:10.1146/annurev.pathol.2.010506.091905.

External links

- American Cancer Society's Detailed Guide: Endometrial Cancer

- U.S. National Cancer Institute: Endometrial cancer

- NIH Endometrial cancer fact page

- Anatomical pathology images

- MedPix endometrial cancer images

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||