Empennage

| Empennage | |

|---|---|

| |

| The empennage of a Boeing 747-200 | |

The empennage (/ˌɑːmpɨˈnɑːʒ/ or /ˈɛmpɨnɪdʒ/),[1][2] also known as the tail or tail assembly, of most aircraft[1][2] gives stability to the aircraft, in a similar way to the feathers on an arrow;[3] the term derives from the French for this.[4] Most aircraft feature empennage incorporating vertical and horizontal stabilising surfaces which stabilise the flight dynamics of pitch and yaw,[1][2] as well as housing control surfaces.

In spite of effective control surfaces, many early aircraft that lacked stabilising empennage were virtually unflyable. Today, only a few (often relatively unstable) heavier than air aircraft are able to fly without empennage ("tailless").

Structure

Structurally, the empennage consists of the entire tail assembly, including the fin, the tailplane and the part of the fuselage to which these are attached.[1][2] On an airliner this would be all the flying and control surfaces behind the rear pressure bulkhead.

The front, usually fixed section of the tailplane is called the horizontal stabilizer and is used to balance and share lifting loads of the mainplane dependent on centre of gravity considerations by limiting oscillations in pitch. The rear section is called the elevator and is usually hinged to the horizontal stabilizer. The elevator is a movable airfoil that controls changes in pitch, the up-and-down motion of the aircraft's nose. Some aircraft employ an all-moving stabilizer and elevators in one unit, known as a stabilator.[1][2]

The vertical tail structure (or fin) has a fixed front section called the vertical stabilizer, used to restrict side-to-side motion of the aircraft (yawing). The rear section of the vertical fin is the rudder, a movable airfoil that is used to turn the aircraft in combination with the ailerons.[1][2]

Some aircraft are fitted with a tail assembly that is hinged to pivot in two axes forward of the fin and stabilizer, in an arrangement referred to as a movable tail. The entire empennage is rotated vertically to actuate the horizontal stabiliser, and sideways to actuate the fin.[5]

The aircraft's cockpit voice recorder and flight data recorder are often located in the empennage, because the aft of the aircraft provides better protection for these in most aircraft crashes.

Trim

In some aircraft trim devices are provided to eliminate the need for the pilot to maintain constant pressure on the elevator or rudder controls.[5][6]

The trim device may be:

- a trim tab on the rear of the elevators or rudder which act to change the aerodynamic load on the surface. Usually controlled by a cockpit wheel or crank.[5][7]

- an adjustable stabilizer into which the stabilizer may be hinged at its spar and adjustably jacked a few degrees in incidence either up or down. Usually controlled by a cockpit crank.[5][8]

- a bungee trim system which uses a spring to provide an adjustable preload in the controls. Usually controlled by a cockpit lever.[5][6]

- an anti-servo tab used to trim some elevators and stabilators as well as increased control force feel. Usually controlled by a cockpit wheel or crank.[5]

- a servo tab used to move the main control surface, as well as act as a trim tab. Usually controlled by a cockpit wheel or crank.[5]

Multi-engined aircraft often have trim tabs on the rudder to reduce the pilot effort required to keep the aircraft straight in situations of asymmetrical thrust, such as single engine operations.[7]

Tail configurations

Aircraft empennage designs may be classified broadly according to the fin and tailplane configurations.

The overall shapes of individual tail surfaces (tailplane planforms, fin profiles) are similar to Wing planforms.

Tailplanes

The tailplane comprises the tail-mounted fixed horizontal stabiliser and movable elevator. Besides its planform, it is characterised by:

- Number of tailplanes - from 0 (Tailless or canard) to 3 (Roe triplane)

- Location of tailplane - mounted high, mid or low on the fuselage, fin or tail booms.

- Fixed stabiliser and movable elevator surfaces, or a single combined stabilator or flying tail.[9] (General Dynamics F-111)

Some locations have been given special names:

- Cruciform tail - The horizontal stabilizers are placed midway up the vertical stabilizer, giving the appearance of a cross when viewed from the front. Cruciform tails are often used to keep the horizontal stabilizers out of the engine wake, while avoiding many of the disadvantages of a T-tail. Examples include the Hawker Sea Hawk and Douglas A-4 Skyhawk.

- T-tail - The horizontal stabilizer is mounted on top of the fin, creating a "T" shape when viewed from the front. T-tails keep the stabilizers out of the engine wake, and give better pitch control. T-tails have a good glide ratio, and are more efficient on low speed aircraft. However, T-tails are more likely to enter a deep stall, and are more difficult to recover from a spin. T-tails must be stronger, and therefore heavier than conventional tails. T-tails also have a larger radar cross section. Examples include the Gloster Javelin, Boeing 727 and McDonnell Douglas DC-9.

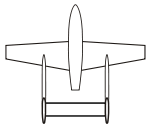

Fuselage mounted |

Cruciform |

T-tail |

Flying tailplane |

Fins

The fin comprises the fixed vertical stabiliser and rudder. Besides its profile, it is characterised by:

- Number of fins - usually one or two.

- Location of fins - on the fuselage (over or under), tailplane, tail booms or wings

Twin fins may be mounted at various points:

- Twin tail A twin tail, also called an H-tail, consists of two small vertical stabilizers on either side of the horizontal stabilizer. Examples include the Antonov An-225 Mriya, B-25 Mitchell, Avro Lancaster, and ERCO Ercoupe.

- Twin boom A twin boom has two fuselages or booms, with a vertical stabilizer on each, and a horizontal stabilizer between them. Examples include the P-38 Lightning, de Havilland Vampire, Sadler Vampire, and Edgley Optica.

- Wing mounted midwing as on the F7U Cutlass or on the wing tips as on the Handley Page Manx and Rutan Long-EZ

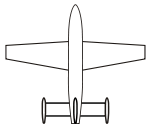

Tailplane mounted |

Twin tailboom |

Wing mounted |

Unusual fin configurations include:

- No fin - as on the McDonnell Douglas X-36. This configuration is sometimes incorrectly referred to as "tailless".

- Multiple fins - examples include the Lockheed Constellation (three), Bellanca 14-13 (three), and the Northrop Grumman E-2 Hawkeye (four).

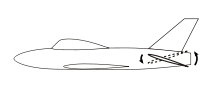

- Ventral fin - underneath the fuselage. Often used in addition to a conventional fin as on the (North American X-15 and Dornier Do 335).

Triple fins |

Ventral fin |

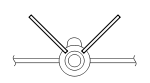

V and X tails

An alternative to the fin-and-tailplane approach is provided by the V-tail and X-tail designs. Here, the tail surfaces are set at diagonal angles, with each surface contributing to both pitch and yaw. The control surfaces, sometimes called ruddervators, act differentially to provide yaw control (in place of the rudder) and act together to provide pitch control (in place of the elevator).[1]

- V tail: A V-tail can be lighter than a conventional tail in some situations and produce less drag, as on the Fouga Magister trainer, Northrop Grumman RQ-4 Global Hawk RPV and X-37 spacecraft. A V-tail may also have a smaller radar signature. Other aircraft featuring a V-tail include the Beechcraft Model 35 Bonanza, and Davis DA-2. A slight modification to the V-tail can be found on the Waiex and Monnet Moni called a Y-tail.

- X tail: The Lockheed XFV and Convair XFY Pogo both featured "X" tails, which were reinforced and fitted with a wheel on each surface so that the craft could sit on its tail and take off and land vertically.

- Pelikan: The Pelikan tail is an all-flying variation on the V tail. It was proposed for the Boeing X-32 but abandoned, and has not yet been used on any aircraft. The design is said to have the advantages of greater pitch control and a smaller radar signature.

V-tail |

Inverted V-tail |

X-tail |

Pelikan tail |

Tailless

A tailless aircraft (often tail-less) traditionally has all its horizontal control surfaces on its main wing surface. It has no horizontal stabilizer - either tailplane or canard foreplane (nor does it have a second wing in tandem arrangement). A 'tailless' type usually still has a vertical stabilising fin (vertical stabilizer) and control surface (rudder). However, NASA adopted the 'tailless' description for the novel X-36 research aircraft which has a canard foreplane but no vertical fin.[citation needed]

The most successful tailless configuration has been the tailless delta, especially for combat aircraft.[citation needed]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 Crane, Dale: Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition, page 194. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ISBN 1-56027-287-2

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 Aviation Publishers Co. Limited, From the Ground Up, page 10 (27th revised edition) ISBN 0-9690054-9-0

- ↑ Air Transport Association (10 November 2011). "ATA Airline Handbook Chapter 5: How Aircraft Fly". Archived from the original on 10 November 2011. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ "Empannage". Oxford Dictionaries Online. Oxford Dictionaries. Retrieved 5 March 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 5.5 5.6 Aviation Publishers Co. Limited, From the Ground Up, page 14 (27th revised edition) ISBN 0-9690054-9-0

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Reichmann, Helmet: Flying Sailplanes, page 26. Thompson Publications, 1980.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Transport Canada: Flight Training Manual 4th Edition, page 12. Gage Educational Publishing Company, 1994. ISBN 0-7715-5115-0

- ↑ Crane, Dale: Dictionary of Aeronautical Terms, third edition, page 524. Aviation Supplies & Academics, 1997. ISBN 1-56027-287-2

- ↑ Anderson, John D., Introduction to Flight, 5th ed, p 517

| ||||||||||||||