Electroscope

An electroscope is an early scientific instrument that is used to detect the presence and magnitude of electric charge on a body. It was the first electrical measuring instrument. The first electroscope, a pivoted needle called the versorium, was invented by British physician William Gilbert around 1600.[1] The pith-ball electroscope and the gold-leaf electroscope are two classical types of electroscope that are still used in physics education to demonstrate the principles of electrostatics. A type of electroscope is also used in the quartz fiber radiation dosimeter. Electroscopes were used by the Austrian scientist Victor Hess in the discovery of cosmic rays.

Electroscopes detect electric charge by the motion of a test object due to the Coulomb electrostatic force. The electric potential or voltage of an object equals its charge divided by its capacitance, so electroscopes can be regarded as crude voltmeters. The accumulation of enough charge to detect with an electroscope requires hundreds or thousands of volts, so electroscopes are only used with high voltage sources such as static electricity and electrostatic machines. Electroscopes generally give only a rough, qualitative indication of the magnitude of the charge; an instrument that measures charge quantitatively is called an electrometer.

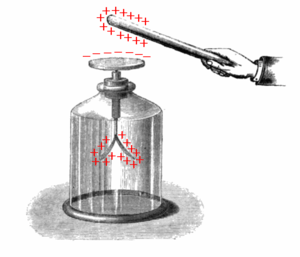

Pith-ball electroscope

A pith-ball electroscope, invented by British weaver's apprentice John Canton in 1754,[2] consists of a small ball of some lightweight nonconductive substance, originally a spongy plant material called pith, although modern electroscopes use plastic balls. The ball is suspended by a silk thread from the hook of an insulated stand. In order to test the presence of a charge on an object, the object is brought near to the uncharged pith ball.[3] If the object is charged, the ball will be attracted to it and move toward it.

The attraction occurs because of induced polarization[4] of the atoms inside the pith ball.[5][6][7][8] The pith is a nonconductor, so the electrons in the ball are bound to atoms of the pith and are not free to leave the atoms and move about in the ball, but they can move a little within the atoms. See diagram at right. If, for example, a positively charged object (B) is brought near the pith ball (A), the negative electrons (blue) in each atom (yellow ovals) will be attracted and move slightly toward the side of the atom nearer the object. The positively charged nuclei (red) will be repelled and will move slightly away. Since the negative charges in the pith ball are now nearer the object than the positive charges (C), their attraction is greater than the repulsion of the positive charges, resulting in a net attractive force.[5] This separation of charge is microscopic, but since there are so many atoms, the tiny forces add up to a large enough force to move a light pith ball.

The pith ball can be charged by touching it to a charged object, so some of the charges on the surface of the charged object move to the surface of the ball. Then the ball can be used to distinguish the polarity of charge on other objects because it will be repelled by objects charged with the same polarity or sign it has, but attracted to charges of the opposite polarity.

Often the electroscope will have a pair of suspended pith balls. This allows one to tell at a glance whether the pith balls are charged. If one of the pith balls is touched to a charged object, charging it, the second one will be attracted and touch it, communicating some of the charge to the surface of the second ball. Now both balls have the same polarity charge, so they repel each other. They hang in an inverted 'V' shape with the balls spread apart. The distance between the balls will give a rough idea of the magnitude of the charge.

Pith-ball Electroscope in 19th Century,a pig swallowed a radium needle,it took a gold-leaf electroscope to find it.Early story on locating a radium needle in a pig.Dr. Taft began working with radium in 1933. Radium is used in very small quantities for the treatment of medical diseases. The quantities were typically about the size of a quarter inch of pencil lead. These radium sources could cost as much as $12,000 each in 1938. Dr. Taft employed an early homemade electroscope for his routine exposure measurements when working with the radium. A colleague requested that Dr. Taft assist him in locating a lost 75 mg radium source. He used his electroscope and then after locating the source began improvements to his instrument. His instrument became known as the “Radium Hound”.

Dr. Taft worked with charging devices for electroscopes and various derivations as early as 1926. He responded to a request for locating a lost radium source in a doctor’s office. He used his electroscope and then after locating the source began improvements to his instrument. Radium is used in very small quantities for the treatment of medical diseases. The quantities were typically about the size of a quarter inch of pencil lead. These radium sources could cost as much as $12,000 each in 1938. His instrument became known as the “Radium Hound”. In 1944, Dr Taft was Professor of Radiology at the Medical College of Charleston.

Gold-leaf electroscope

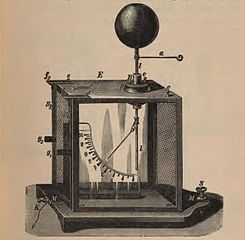

The gold-leaf electroscope was developed in 1787 by British clergyman and physicist Abraham Bennet,[2] as a more sensitive instrument than pith ball or straw blade electroscopes then in use.[9] It consists of a vertical metal rod, usually brass, from the end of which hang two parallel strips of thin flexible gold leaf. A disk or ball terminal is attached to the top of the rod, where the charge to be tested is applied.[9] To protect the gold leaves from drafts of air they are enclosed in a glass bottle, usually open at the bottom and mounted over a conductive base. Often there are grounded metal plates or foil strips in the bottle flanking the gold leaves on either side. These are a safety measure; if an excessive charge is applied to the delicate gold leaves, they will touch the grounding plates and discharge before tearing. They also capture charge leaking through the air that could accumulate on the glass walls, and increase the sensitivity of the instrument. In precision instruments the inside of the bottle was occasionally evacuated, to prevent the charge on the terminal from leaking off through ionization of the air.

When the metal terminal is touched with a charged object, the gold leaves spread apart in a 'V'. This is because some of the charge on the object is conducted through the terminal and metal rod to the leaves.[9] Since they receive the same sign charge they repel each other and thus diverge. If the terminal is grounded by touching it with a finger, the charge is transferred through the human body into the earth and the gold leaves close together.

The electroscope can also be charged without touching it to a charged object, by electrostatic induction. If a charged object is brought near the electroscope terminal, the leaves also diverge, because the electric field of the object causes the charges in the electroscope rod to separate. Charges of the opposite polarity to the charged object are attracted to the terminal, while charges with the same polarity are repelled to the leaves, causing them to spread. If the electroscope terminal is grounded while the charged object is nearby, by touching it momentarily with a finger, the same polarity charges in the leaves drain away to ground, leaving the electroscope with a net charge of opposite polarity to the object. The leaves close because the charge is all concentrated at the terminal end. When the charged object is moved away, the charge at the terminal spreads into the leaves, causing them to spread apart again.

- Gold-leaf electroscopes

-

"Condensing" electroscope, Rome University physics dept.

-

Electroscope from about 1910 with grounding electrodes inside jar, as described above

-

-

Kolbe electrometer, precision form of gold-leaf instrument. This has a light pivoted aluminum vane hanging next to a vertical metal plate. When charged the vane is repelled by the plate and hangs at an angle.

-

Homemade electroscope, 1900

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Gilbert, William; Edward Wright (1893). On the Lodestone and Magnetic Bodies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 79. a translation by P. Fleury Mottelay of William Gilbert (1600) Die Magnete, London

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Derry, Thomas K.; Williams, Trevor (1993). A Short History of Technology from Earliest Times to A.D.1900. Courier Dover. ISBN 0-486-27472-1. p.609

- ↑ Elliott (1999)

- ↑ Sherwood, Bruce A.; Ruth W. Chabay (2011). Matter and Interactions, 3rd Ed.. USA: John Wiley and Sons. pp. 594–596. ISBN 0-470-50347-5.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Kaplan MCAT Physics 2010-2011. USA: Kaplan Publishing. 2009. p. 329. ISBN 1-4277-9875-3.

- ↑ Paul E. Tippens, Electric Charge and Electric Force, Powerpoint presentation, p.27-28, 2009, S. Polytechnic State Univ. on DocStoc.com website

- ↑ Henderson, Tom (2011). "Charge and Charge Interactions". Static Electricity, Lesson 1. The Physics Classroom. Retrieved 2012-01-01.

- ↑ Winn, Will Winn (2010). Introduction to Understandable Physics Vol. 3: Electricity, Magnetism and Ligh. USA: Author House. p. 20.4. ISBN 1-4520-1590-2.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 [Anon.] (2001)

Bibliography

- "Fleming, J. A., Electroscope". Encyclopaedia Britannica, 11th Ed. 9. The Encyclopaedia Britannica Co. 1910. pp. 239–240.

- Elliott, P. (1999). "Abraham Bennet F.R.S. (1749-1799): a provincial electrician in eighteenth-century England" (PDF). Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London 53 (1): 59–78. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1999.0063.{Audit}

External links

- "Pith-ball electroscope". Physics demonstration resource. St. Mary's University. Retrieved 2007-09-02.

- "Computer simulation of electroscopes". Molecular Workbench. Concord Consortium.

- "Pith Ball and Charged Rod Video". St. Mary's Physics YouTube Channel. St. Mary's Physics Online.