Electrodialysis

Method

The E stream is the electrode stream that flows past each electrode in the stack. This stream may consist of the same composition as the feed stream (e.g., sodium chloride) or may be a separate solution containing a different species (e.g., sodium sulfate).[5] Depending on the stack configuration, anions and cations from the electrode stream may be transported into the C stream, or anions and cations from the D stream may be transported into the E stream. In each case, this transport is necessary to carry current across the stack and maintain electrically neutral stack solutions.

Anode and cathode reactions

Reactions take place at each electrode. At the cathode,[3]

2e- + 2 H2O → H2 (g) + 2 OH-

while at the anode,[3]

H2O → 2 H+ + ½ O2 (g) + 2e- or 2 Cl- → Cl2 (g) + 2e-

Small amounts of hydrogen gas are generated at the cathode and small amounts of either oxygen or chlorine gas (depending on composition of the E stream and end ion exchange membrane arrangement) at the anode. These gases are typically subsequently dissipated as the E stream effluent from each electrode compartment is combined to maintain a neutral pH and discharged or re-circulated to a separate E tank. However, some (e.g.,) have proposed collection of hydrogen gas for use in energy production.

Efficiency

Current efficiency is a measure of how effective ions are transported across the ion exchange membranes for a given applied current. Typically current efficiencies >80% are desirable in commercial stacks to minimize energy operating costs. Low current efficiencies indicate water splitting in the diluate or concentrate streams, shunt currents between the electrodes, or back-diffusion of ions from the concentrate to the diluate could be occurring.

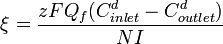

Current efficiency is calculated according to:[8]

where

= current utilization efficiency

= current utilization efficiency

= charge of the ion

= charge of the ion

= Faraday constant, 96,485 Amp-s/mol

= Faraday constant, 96,485 Amp-s/mol

= diluate flow rate, L/s

= diluate flow rate, L/s

= diluate ED cell inlet concentration, mol/L

= diluate ED cell inlet concentration, mol/L

= diluate ED cell outlet concentration, mol/L

= diluate ED cell outlet concentration, mol/L

= number of cell pairs

= number of cell pairs

= current, Amps.

= current, Amps.

Current efficiency is generally a function of feed concentration.[9]

Applications

In application, electrodialysis systems can be operated as continuous production or batch production processes. In a continuous process, feed is passed through a sufficient number of stacks placed in series to produce the final desired product quality. In batch processes, the diluate and/or concentrate streams are re-circulated through the electrodialysis systems until the final product or concentrate quality is achieved.

Electrodialysis is usually applied to deionization of aqueous solutions. However, desalting of sparingly conductive aqueous organic and organic solutions is also possible. Some applications of electrodialysis include:[2][4][5][10]

- Large scale brackish and seawater desalination and salt production.

- Small and medium scale drinking water production (e.g., towns & villages, construction & military camps, nitrate reduction, hotels & hospitals)

- Water reuse (e.g., industrial laundry wastewater, produced water from oil/gas production, cooling tower makeup & blowdown, metals industry fluids, wash-rack water)

- Pre-demineralization (e.g., boiler makeup & pretreatment, ultrapure water pretreatment, process water desalination, power generation, semiconductor, chemical manufacturing, food and beverage)

- Food processing

- Agricultural water (e.g., water for greenhouses, hydroponics, irrigation, livestock)

- Glycol desalting (e.g., antifreeze / engine-coolants, capacitor electrolyte fluids, oil and gas dehydration, conditioning and processing solutions, industrial heat transfer fluids, secondary coolants from heating, venting, and air conditioning (HVAC))

- Glycerin Purification

The major application of electrodialysis has historically been the desalination of brackish water or seawater as an alternative to RO for potable water production and seawater concentration for salt production (primarily in Japan).[4] In normal potable water production without the requirement of high recoveries, RO (Reverse Osmosis) is generally believed to be more cost-effective when total dissolved solids (TDS) are 3,000 parts per million (ppm) or greater, while electrodialysis is more cost-effective for TDS feed concentrations less than 3,000 ppm or when high recoveries of the feed are required.

Another important application for electrodialysis is the production of pure water and ultrapure water by electrodeionization (EDI). In EDI, the purifying compartments and sometimes the concentrating compartments of the electrodialysis stack are filled with ion exchange resin. When fed with low TDS feed (e.g., feed purified by RO), the product can reach very high purity levels (e.g., 18 MΩ-cm). The ion exchange resins act to retain the ions, allowing these to be transported across the ion exchange membranes. The main usage of EDI systems are in electronics, pharmaceutical, power generation, and cooling tower applications.

Limitations

Electrodialysis has inherent limitations, working best at removing low molecular weight ionic components from a feed stream. Non-charged, higher molecular weight, and less mobile ionic species will not typically be significantly removed. Also, in contrast to RO, electrodialysis becomes less economical when extremely low salt concentrations in the product are required and with sparingly conductive feeds: current density becomes limited and current utilization efficiency typically decreases as the feed salt concentration becomes lower, and with fewer ions in solution to carry current, both ion transport and energy efficiency greatly declines. Consequently, comparatively large membrane areas are required to satisfy capacity requirements for low concentration (and sparingly conductive) feed solutions. Innovative systems overcoming the inherent limitations of electrodialysis (and RO) are available; these integrated systems work synergistically, with each sub-system operating in its optimal range, providing the least overall operating and capital costs for a particular application.[11]

As with RO, electrodialysis systems require feed pretreatment to remove species that coat, precipitate onto, or otherwise "foul" the surface of the ion exchange membranes. This fouling decreases the efficiency of the electrodialysis system. Species of concern include calcium and magnesium hardness, suspended solids, silica, and organic compounds. Water softening can be used to remove hardness, and micrometre or multimedia filtration can be used to remove suspended solids. Hardness in particular is a concern since scaling can build up on the membranes. Various chemicals are also available to help prevent scaling. Also, electrodialysis reversal systems seek to minimize scaling by periodically reversing the flows of diluate and concentrate and polarity of the electrodes.

References

List of references and sources of additional information.

- ↑ Davis, T.A., "Electrodialysis", in Handbook of Industrial Membrane Technology, M.C. Porter, ed., Noyes Publications, New Jersey (1990)

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Strathmann, H., "Electrodialysis", in Membrane Handbook, W.S.W. Ho and K.K. Sirkar, eds., Van Nostrand Reinhold, New York (1992)

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Mulder, M., Basic Principles of Membrane Technology, Kluwer, Dordrecht (1996)

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Sata, T., Ion Exchange Membranes: Preparation, Characterization, Modification and Application, Royal Society of Chemistry, London (2004)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 Strathmann, H., Ion-Exchange Membrane Separation Processes, Elsevier, New York (2004)

- ↑ ED - Turning Seawater into Drinking Water

- ↑ AWWA, Electrodialysis and Electrodialysis Reversal, American Water Works Association, Denver (1995)

- ↑ Shaffer, L., and Mintz, M., "Electrodialysis" in Principles of Desalination, Spiegler, K., and Laird, A., eds., 2nd Ed., Academic Press, New York (1980)

- ↑ Current Utilization Efficiency

- ↑ ED Selected Applications

- ↑ How HEEPM Works

- A. A. Zagorodni, Ion Exchange Materials: Properties and Applications, Elsevier, Amsterdam, (2006) Chapter 17 - a simple introduction to electrodialysis and description of different electromembrane processes

See also

- Salinity gradient power

- Water desalination

- Electrodialysis reversal

- Reverse Osmosis

- Proton exchange membrane