Electric susceptibility

In electromagnetism, the electric susceptibility  (latin: susceptibilis “receptive”) is a dimensionless proportionality constant that indicates the degree of polarization of a dielectric material in response to an applied electric field. The greater the electric susceptibility, the greater the ability of a material to polarize in response to the field, and thereby reduce the total electric field inside the material (and store energy). It is in this way that the electric susceptibility influences the electric permittivity of the material and thus influences many other phenomena in that medium, from the capacitance of capacitors to the speed of light.[1][2]

(latin: susceptibilis “receptive”) is a dimensionless proportionality constant that indicates the degree of polarization of a dielectric material in response to an applied electric field. The greater the electric susceptibility, the greater the ability of a material to polarize in response to the field, and thereby reduce the total electric field inside the material (and store energy). It is in this way that the electric susceptibility influences the electric permittivity of the material and thus influences many other phenomena in that medium, from the capacitance of capacitors to the speed of light.[1][2]

Definition of volume susceptibility

Electric susceptibility is defined as the constant of proportionality (which may be a tensor) relating an electric field E to the induced dielectric polarization density P such that:

where

-

is the polarization density;

is the polarization density; -

is the electric permittivity of free space;

is the electric permittivity of free space; -

is the electric susceptibility;

is the electric susceptibility; -

is the electric field.

is the electric field.

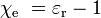

The susceptibility is also related to the polarizability of individual particles in the medium by the Clausius-Mossotti relation. The susceptibility is related to its relative permittivity  by:

by:

So in the case of a vacuum:

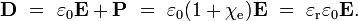

At the same time, the electric displacement D is related to the polarization density P by:

Molecular polarizability

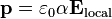

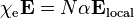

A similar parameter exists to relate the magnitude of the induced dipole moment p of an individual molecule to the local electric field E that induced the dipole. This parameter is the molecular polarizability and the dipole moment resulting from the local electric field Elocal is given by:

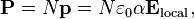

This introduces a complication however, as locally the field can differ significantly from the overall applied field. We have:

where P is the polarization per unit volume, and N is the number of molecules per unit volume contributing to the polarization. Thus, if the local electric field is parallel to the ambient electric field, we have:

Thus only if the local field equals the ambient field can we write:

Nonlinear susceptibility

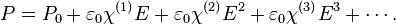

In many materials the polarizability starts to saturate at high values of electric field. This saturation can be modelled by a nonlinear susceptibility. These susceptibilities are important in nonlinear optics and lead to effects such as second harmonic generation (such as used to convert infrared light into visible light, in green laser pointers).

The standard definition of nonlinear susceptibilities in SI units is via a Taylor expansion of the polarization's reaction to electric field:[3]

(Except in ferroelectric materials, the built-in polarization is zero,  .)

The first susceptibility term,

.)

The first susceptibility term,  , corresponds to the linear susceptibility described above. While this first term is dimensionless, the subsequent nonlinear susceptibilities

, corresponds to the linear susceptibility described above. While this first term is dimensionless, the subsequent nonlinear susceptibilities  have units of (m/V)n-1.

have units of (m/V)n-1.

The nonlinear susceptibilities can be generalized to anisotropic materials (where each susceptibility  becomes an n+1-rank tensor).

becomes an n+1-rank tensor).

Dispersion and causality

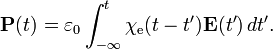

In general, a material cannot polarize instantaneously in response to an applied field, and so the more general formulation as a function of time is

That is, the polarization is a convolution of the electric field at previous times with time-dependent susceptibility given by  . The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines

. The upper limit of this integral can be extended to infinity as well if one defines  for

for  . An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility

. An instantaneous response corresponds to Dirac delta function susceptibility  .

.

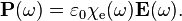

It is more convenient in a linear system to take the Fourier transform and write this relationship as a function of frequency. Due to the convolution theorem, the integral becomes a simple product,

This frequency dependence of the susceptibility leads to frequency dependence of the permittivity. The shape of the susceptibility with respect to frequency characterizes the dispersion properties of the material.

Moreover, the fact that the polarization can only depend on the electric field at previous times (i.e.  for

for  ), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility

), a consequence of causality, imposes Kramers–Kronig constraints on the susceptibility  .

.

See also

- Application of tensor theory in physics

- Magnetic susceptibility

- Maxwell's equations

- Permittivity

- Clausius-Mossotti relation

- Linear response function

- Green–Kubo relations

References

- ↑ "Electric susceptibility". Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Cardarelli, François (2000, 2008). Materials Handbook: A Concise Desktop Reference (2nd ed.). London: Springer-Verlag. pp. 524 (Section 8.1.16). doi:10.1007/978-1-84628-669-8. ISBN 978-1-84628-668-1.

- ↑ Paul N. Butcher, David Cotter, The Elements of Nonlinear Optics