Elagabalium

The Elagabalium was a temple built by the Roman emperor Elagabalus, located on the north-east corner of the Palatine Hill. During Elagabalus' reign from 218 until 222, the Elagabalium was the center of a controversial religious cult, dedicated to Deus Sol Invictus, of which the emperor himself was the high priest.

History

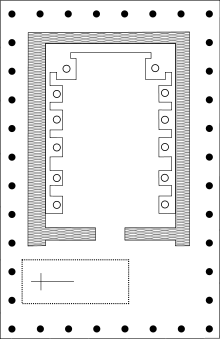

The temple was a colonnaded structure some 70 metres by 40 metres, in front of the Colosseum, within a colonnaded enclosure. The temple platform was originally built under Domitian between 81 and 96, and may have been a place of worship to Jupiter.[1] The remnants of this terrace are still visible today at the north-east corner of the Palatine Hill.

When Elagabalus became emperor in 218 the temple was expanded and rededicated to the god El-Gabal, the patron deity of his homeplace Emesa in Syria.[2] Elagabalus renamed the god Deus Sol Invictus and personally led a cult that worshipped this deity. Deus Sol Invictus was personified by a conical black stone, which has been suggested to have been a piece of meteorite rock.[3]

After Elagabalus' death the temple was again dedicated to Jupiter by Severus Alexander. A second, smaller temple to the god El-Gabal was built where the church of Santa Croce in Gerusalemme now stands.

The cult of Elagabalus

Since the reign of Septimius Severus, sun worship had increased throughout the Empire.[4] Elagabalus saw this as an opportunity to set up his god, El-Gabal, as the chief deity of the Roman pantheon. El-Gabal, renamed Deus Sol Invictus or God the Undefeated Sun, was placed over even Jupiter.[5] As a sign of the union between the two religions, Elagabalus gave either Astarte, Minerva, Urania, or some combination of the three, to El-Gabal as a wife.[6] Herodian writes that Elagabalus forced senators to watch while he danced around the altar of El-Gabal to the sound of drums and cymbals,[2] and that each summer solstice became a great festival to El-Gabal popular with the masses because of its widely distributed food.[6] During this festival, Elagabalus placed El-Gabal on a chariot adorned with gold and jewels, which he paraded through the city, after which he threw gifts into the Roman crowds:[6]

After thus bringing the god out and placing him in the temple, Heliogabalus performed the rites and sacrifices described above; then, climbing to the huge, lofty towers which he had erected, he threw down, indiscriminately, cups of gold and silver, clothing, and cloth of every type to the mob below.[6]

The most sacred relics from the Roman religion were transferred from their respective shrines to the Elagabalium, including the Great Mother, the fire of Vesta, the Shields of the Salii and the Palladium.[7] Ancient history records lurid tales of human sacrifice taking place inside the temple, involving children which were collected all over Italy from the richest and noblest families.[8][9] The religious excesses of Elagabalus' reign eventually contributed to his demise. On March 11, 222, Elagabalus was killed by members of the Praetorian Guard, and replaced by his cousin Severus Alexander. Elagabalus' religious edicts were reversed, and the statues which had been moved to the Elagabalium were restored to their original shrines.[10]

Notes

- ↑ Van Zoonen, Lauren. "Temple of Elagabal". Livius.org. Archived from the original on 2007-04-16. Retrieved 2007-08-08.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Herodian, Roman History V.5

- ↑ Herodian, Roman History V.3.5

- ↑ Halsberghe, Gaston H. (1972). The Cult of Sol Invictus. Leiden: Brill. p. 36.

- ↑ Cassius Dio, Roman History LXXX.11

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Herodian, Roman History V.6

- ↑ Augustan History, Life of Elagabalus I.3

- ↑ Augustan History, Life of Elagabalus I.8

- ↑ Casssius Dio, Roman History LXXX.11.3

- ↑ Herodian, Roman History VI.1

External links

- The Elagabalium, history and description from livius.org