Einstein ring

| Gravitational Lensing |

|---|

|

|

Introduction Formalism Strong lensing Microlensing Weak lensing |

|

Strong Lens Systems Abell 1689 · Abell 2218 CL0024+17 · Bullet Cluster QSO2237+0305 · SDSSJ0946+1006 B1359+154 · QSO 0957+561 |

|

Surveys Strong: CLASS · SLACS (SDSS) Micro: OGLE Weak: DLS · Pan-STARRS · CFHTLS . DES · LSST · SNAP · DESTINY |

In observational astronomy an Einstein ring is the deformation of the light from a source (such as a galaxy or star) into a ring through gravitational lensing of the source's light by an object with an extremely large mass (such as another galaxy, or a black hole). This occurs when the source, lens and observer are all aligned. The first complete Einstein ring, designated B1938+666, was discovered by collaboration between astronomers at the University of Manchester and NASA's Hubble Space Telescope in 1998.[1]

Introduction

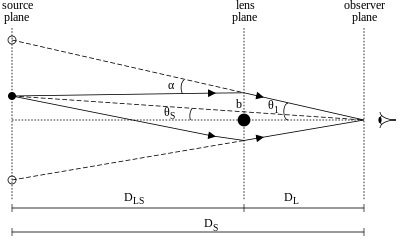

Gravitational lensing is predicted by Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity. Instead of light from a source traveling in a straight line (in three dimensions), it is bent by the presence of a massive body, which distorts spacetime. An Einstein Ring is a special case of gravitational lensing, caused by the exact alignment of the source, lens and observer. This results in a symmetry around the lens, causing a ring-like structure.

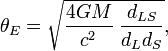

The size of an Einstein ring is given by the Einstein radius. In radians, it is

where

-

is the gravitational constant,

is the gravitational constant, -

is the mass of the lens,

is the mass of the lens, -

is the speed of light,

is the speed of light, -

is the angular diameter distance to the lens,

is the angular diameter distance to the lens, -

is the angular diameter distance to the source, and

is the angular diameter distance to the source, and -

is the angular diameter distance between the lens and the source.

is the angular diameter distance between the lens and the source.

Note that, over cosmological distances  in general.

in general.

History

The bending of light by a gravitational body was predicted by Einstein in 1912, a few years before the publication of General Relativity in 1916 (see Renn et al. 1997). The ring effect was first mentioned in academic literature by Orest Chwolson in 1924. Albert Einstein remarked upon this effect in 1936 in a paper prompted by a letter by a Czech engineer, R W Mandl , but stated

Of course, there is no hope of observing this phenomenon directly. First, we shall scarcely ever approach closely enough to such a central line. Second, the angle β will defy the resolving power of our instruments.—Science vol 84 p 506 1936

In this statement, β is the Einstein Radius currently denoted by  (see above). However, Einstein was only considering the chance of observing Einstein rings produced by stars, which is low; however, the chance of observing those produced by larger lenses such as galaxies or black holes is higher since the angular size of an Einstein ring increases with the mass of the lens.

(see above). However, Einstein was only considering the chance of observing Einstein rings produced by stars, which is low; however, the chance of observing those produced by larger lenses such as galaxies or black holes is higher since the angular size of an Einstein ring increases with the mass of the lens.

Known Einstein rings

Hundreds of gravitational lenses are currently known. About half a dozen of them are partial Einstein rings with diameters up to an arcsecond, although as either the mass distribution of the lenses is not perfectly axially symmetrical, or the source, lens and observer are not perfectly aligned, we have yet to see a perfect Einstein ring. Most rings have been discovered in the radio range.

The first Einstein ring was discovered by Hewett et al. (1988), who observed the radio source MG1131+0456 using the Very Large Array.[2] The first complete Einstein ring to be discovered was B1938+666, which was found by King et al. (1998) via optical follow-up with the Hubble Space Telescope of a gravitational lens imaged with MERLIN.[3][4]

| Name | Location (RA, dec) | Radius | Arc size | Optical/radio | Discovery |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FOR J0332-3557 | 03h:32m:59s:94, -35°57'51".7, J2000 | 1".48 | Partial, 260° | Radio | Cabanac (2005) |

| SDSSJ0946+1006 | 09h 46m 56.s68, +10° 06' 52."6 J2000 | Optical | Gavazzi (2008) | ||

| MG1131 + 0456 |

Extra rings

Using the Hubble Space Telescope, a double ring has been found by Raphael Gavazzi of the STScI and Tommaso Treu of the University of California, Santa Barbara. This arises from the light from three galaxies at distances of 3, 6 and 11 billion light years. Such rings help in understanding the distribution of dark matter, dark energy, the nature of distant galaxies, and the curvature of the universe. The odds of finding such a double ring are 1 in 10,000. Sampling 50 suitable double rings would provide astronomers with a more accurate measurement of the dark matter content of the universe and the equation of state of the dark energy to within 10 percent precision.[5]

A simulation

To the right is a simulation depicting a zoom on a Schwarzschild black hole in front of the Milky Way. The first Einstein ring corresponds to the most distorted region of the picture and is clearly depicted by the galactic disc. The zoom then reveals a series of 4 extra rings, increasingly thinner and closer to the black hole shadow. They are easily seen through the multiple images of the galactic disk. The odd-numbered rings correspond to points which are behind the black hole (from the observer's position) and correspond here to the bright yellow region of the galactic disc (close to the galactic center), whereas the even-numbered rings correspond to images of objects which are behind the observer, which appear bluer since the corresponding part of the galactic disc is thinner and hence dimmer here.

See also

- Einstein Cross

- Einstein radius

- Gravitational lens

- Conservation of angular momentum

References

- ↑ "A Bull's Eye for MERLIN and the Hubble". University of Manchester. 27 March 1998.

- ↑ "Discovery of the First "Einstein Ring" Gravitational Lens". NRAO. 2000. Retrieved 2012-02-08.

- ↑ "A Bull's Eye for MERLIN and the Hubble". University of Manchester. 27 March 1998.

- ↑ Browne, Malcolm W. (1998-03-31). "'Einstein Ring' Caused by Space Warping Is Found". The New York Times. Retrieved 2010-05-01.

- ↑ "Hubble Finds Double Einstein Ring". http://hubblesite.org. Space Telescope Science Institute. Retrieved 2008-01-26.

Journals

- Cabanac, R. A.; et al. (2005). "Discovery of a high-redshift Einstein ring". Astronomy and Astrophysics 436 (2): L21–L25. arXiv:astro-ph/0504585. Bibcode:2005A&A...436L..21C. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:200500115. (refers to FOR J0332-3357)

- Chwolson, O (1924). "Über eine mögliche Form fiktiver Doppelsterne". Astronomische Nachrichten 221 (20): 329. Bibcode:1924AN....221..329C. doi:10.1002/asna.19242212003. (The first paper to propose rings)

- Einstein, Albert (1936). "Lens-like Action of a Star by the Deviation of Light in the Gravitational Field". Science 84 (2188): 506–507. Bibcode:1936Sci....84..506E. doi:10.1126/science.84.2188.506. PMID 17769014. (The famous Einstein Ring paper)

- Hewitt, J (1988). "Unusual radio source MG1131+0456 - A possible Einstein ring". Nature 333: 537. Bibcode:1988Natur.333..537H. doi:10.1038/333537a0.

- Renn, Jurgen; Tilman Sauer and John Stachel (1997). "The Origin of Gravitational Lensing: A Postscript to Einstein's 1936 Science paper". Science 275 (5297): 184–186. Bibcode:1997Sci...275..184R. doi:10.1126/science.275.5297.184. PMID 8985006.

- King, L (1998). "A complete infrared Einstein ring in the gravitational lens system B1938 + 666". MNRAS 295: 41. arXiv:astro-ph/9710171. Bibcode:1998MNRAS.295L..41K. doi:10.1046/j.1365-8711.1998.295241.x.

News

- Barbour, Jeff (2005-04-29). "Nearly perfect Einstein ring discovered". Universe Today. Retrieved 2006-06-15. (refers to FOR J0332-3357)

- "Hubble Finds Double Einstein Ring". Science Daily. 2008-01-12. Retrieved 2008-01-14.

Further reading

- Kochanek, C.S.; C.R. Keeton and B.A. McLeod (2001). "The Importance of Einstein Rings". The Astrophysical Journal 547 (1): 50–59. arXiv:astro-ph/0006116. Bibcode:2001ApJ...547...50K. doi:10.1086/318350.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Einstein Rings. |