Eighteen Arhats

The Eighteen Arhats (Chinese: 十八羅漢/十八阿羅漢; pinyin: Shíbā Luóhàn/Shíbā āLuóhàn; Wade-Giles:Lóhàn) are depicted in Mahayana Buddhism as the original followers of the Buddha who have followed the Eightfold Path and attained the Four Stages of Enlightenment. They have reached the state of Nirvana and are free of worldly cravings. They are charged to protect the Buddhist faith and to await on earth for the coming of Maitreya, a prophesied enlightened Buddha to arrive on earth many millennia after Gautama Buddha's death and nirvana. In China, the eighteen arhats are also a popular subject of Buddhist art.

In China

Originally, the arhats composed of only 10 disciples of Gautama Buddha, although the earliest Indian sutras indicate that only 4 of them, Pindola, Kundadhana, Panthaka and Nakula, were instructed to await the coming of Maitreya.[1] Earliest Chinese representations of the arhats can be traced back to as early as the fourth century,[2] and mainly focused on Pindola who was popularized in art by the book Method for Inviting Pindola (Chinese: 請賓度羅法; pinyin: Qǐng Bīndùluó Fǎ).

Later this number increased to 16 to include patriarchs and other spiritual adepts. Teachings about the Arhats eventually made their way to China where they were called Luohan (羅漢, shortened from a-luo-han a Chinese transcription for Arhat), but it wasn't until 654 AD when the Nandimitrāvadāna (Chinese: 法住記; pinyin: Fǎzhùjì), Record on the Duration of the Law, spoken by the Great arhat Nadimitra, was translated by Xuanzang into Chinese that the names of these arhats were known. For some reason Kundadhana was dropped from this list.[3]

Somewhere between the late Tang Dynasty and early Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period of China two other Luohans were added to the roster increasing the number to 18.[4] But this depiction of having 18 Luohans only gained a foothold in China whereas other areas like Japan continue to revere only sixteen and whose roster differs somewhat. This depiction of having 18 instead of 16 Luohans continues into modern Chinese Buddhist traditions. A cult built around the Luohans as guardians of Buddhist faith gained momentum amongst Chinese Buddhists at the end of the ninth century for they had just been through a period a great persecution under the reign of Emperor Tang Wuzong. In fact the last two additions to this roster, Taming Dragon and Taming Tiger, are thinly veiled swipes against Taoism.

In Chinese art

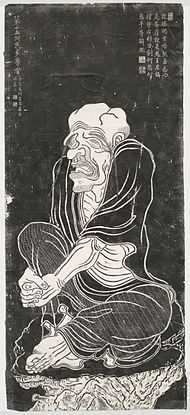

Because no historical records detailing how the Luohans looked like existed there were no distinguishing features to tell the Luohans apart in early Chinese depictions.[5] The first portraits of the 18 Luohans was painted by the monk Guan Xiu (Chinese: 貫休; pinyin: Guànxiū) in 891 AD who at the time was residing in Chengdu. Legend has it that the 18 Luohans knew of Guan Xiu's expert calligraphy and painting skills they appeared to the monk in a dream to make a request that he paint their portraits.[6] The paintings depicted them as foreigners having bushy eyebrows, large eyes, hanging cheeks and high noses. They were seated in landscapes, leaning against pine trees and stones. An additional theme in these paintings were that they were portrayed as being unkempt and "eccentric" which emphasize that they were vagabonds and beggars who have left all worldly desires behind. When Guan Xiu was asked how he came up with the depictions, he answered: "It was in a dream that I saw these Gods and Buddhas. After I woke up, I painted what I saw in the dream. So, I guess I can refer to these Luohans as 'Luohans in a dream'." These portraits painted by Guan Xiu has become the definitive images for the 18 Luohans in Chinese Buddhist iconography, although in modern depiction they bear more Sinitic features and at the same time lost their exaggerated foreign features in exchange for more exaggerated expressions. The paintings were donated by Guan Xiu to the Shengyin Temple in Qiantang (present day Hangzhou) where they are preserved with great care and ceremonious respect.[7] Many prominent artists such as Wu Bin and Ding Guanpeng would later try to faithfully imitate the original paintings.

The Qianlong Emperor was a great admirer of the Luohans and during his visit to see the paintings in 1757, Qianlong not only examined them closely but he also wrote a eulogy to each Luohan image. Copies of these eulogies were presented to the monastery and preserved. In 1764, Qianlong ordered that the paintings held at the Shengyin Monastery be reproduced and engraved onto stone tablets for preservation. These were mounted like facets into a marble stupa for public display. The temple was destroyed during the Taiping Rebellion but copies of ink rubbing of the steles were preserved in and outside of China.[8]

Roster

In the Chinese Tradition, the 18 Luohans are generally presented in the order they are said to have appeared to Guan Xiu, not according to their power: Deer Sitting, Happy, Raised Bowl, Raised Pagoda, Meditating, Oversea, Elephant Riding, Laughing Lion, Open Heart, Raised Hand, Thinking, Scratched Ear, Calico Bag, Plantain, Long Eyebrow, Doorman, Taming Dragon and Taming Tiger.

| Name | Qianlong's Eulogy | Synopsis |

|---|---|---|

|

01. Pindola the Bharadvaja* |

Sitting dignified on a deer, |

Guan Xiu's Dream: Deer Sitting Luohan (Chinese: 騎鹿羅漢; pinyin: Qílù Luóhàn) |

|

02. Kanaka the Vatsa |

Decimating the demons, |

|

|

03. Kanaka the Bharadvaja |

In majestic grandeur, |

|

|

A seven-storey pagoda, |

||

|

05. Nakula* |

Quietly cultivating the mind, |

|

|

06. Bodhidharma |

Bearing the sutras, |

|

|

07. Kalika |

Riding an elephant with a dignified air, |

Elephant Riding Lohan (Chinese: 騎象羅漢; pinyin: Qíxiàng Luóhàn) |

|

08. Vijraputra |

Playful and free of inhibitions, |

|

|

Open the heart and there is Buddha, |

||

|

10. Pantha the Elder* |

Easy and comfortable, |

|

|

11. Rahula |

Pondering and meditating, |

|

|

12. Nagasena |

Leisurely and contented, |

|

|

Buddha of infinite life, |

||

|

14. Vanavasa |

Carefree and leisurely, |

|

|

Compassionate elder, |

||

|

16. Pantha the Younger |

Powerful, husky and tough, |

|

|

In the hands are the spiritual pearl and the holy bowl, |

Taming Dragon Lohan (Chinese: 降龍羅漢; pinyin: Xiánglóng Luóhàn) | |

|

Precious ring with magical powers, |

References

- ↑ M.V. de Visser (1919). The Arhats in China and Japan. Princeton University Press. p. 62. ISBN 9780691117645.

- ↑ Patricia Bjaaland Welch (2008). Chinese art: a guide to motifs and visual imagery. Tuttle Publishing. p. 197. ISBN 9780804838641.

- ↑ John Strong (2004). Relics of the Buddha. Princeton University Press. p. 226. ISBN 9780691117645.

- ↑ Patricia Eichenbaum Karetzky (1996). Court Art of the Tang. University Press of America. p. 128. ISBN 9780761802013.

- ↑ Masako Watanabe (2000). Guanxiu and Exotic Imagery in Rakan Paintings. Orientations, vol. XXXI, no. 4. pp. 34–42.

- ↑ Roy Bates (2007). 10,000 Chinese Numbers. Lulu.com. p. 256. ISBN 9780557006212.

- ↑ Susan Bush and Ilsio-yen Shih (1985). Early Chinese Texts on Painting. Cambridge, MA, and London. p. 314.

- ↑ Harvard University Library.

| ||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||