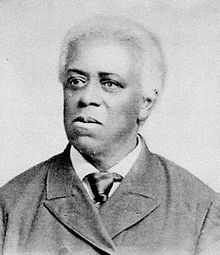

Edward G. Walker

| Edward G. Walker | |

|---|---|

| |

| Edward G. Walker (1830-1901), son of David Walker (abolitionist), one of the first two black men elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature. | |

| Member of Massachusetts State Legislature | |

| In office 1866–1867 | |

Edward Garrison Walker, also known as Edwin Garrison Walker (1830-1901), was an American artisan in Boston who became an attorney in 1861 as one of the first black men to pass the Massachusetts bar. He later became a politician, sharing with Charles Lewis Mitchell the distinction in 1866 of being one of the first two black men elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature. Walker was the son of Eliza and David Walker, an abolitionist, who had written an appeal in 1829 calling for the end of slavery.

An independent thinker, Walker had different ideas than many Republicans, and did not receive renomination to the legislature. He joined the Democratic Party and was nominated by the governor three times to a position as a judge; the Republican-majority legislature rejected Walker each time.[1] In 1896 Walker was nominated as a candidate for United States President by the Negro Party.[1]

Early life

Edward Garrison Walker was born in Boston to Eliza Walker,[nb 1] the widow of David Walker, in 1830.[nb 2] His father is commonly believed to have died of tuberculosis.[2]

At the time when the couple was expecting the birth of Edward, they already had a daughter named Lydia Ann. In 1830 a tuberculosis epidemic in Boston took the lives of Lydia Ann on July 30 and David on August 6. David had collapsed and died at the entrance to his store.[3]

When Walker died, his wife was unable to keep up the annual payments of $266 ("a huge sum for Walker") made to George Parkman for the purchase of their home, and she lost in this very city, when a man of color dies, if he owned any real estate it most get the home. In his pamphlet Appeal, Walker had earlier written: "But I must, really, observe that generally galls into the hands of some white persons. The wife and children of the deceased may weep and lament if they please, but the estate will be kept snug enough of its white possessor."[4]

Eliza Butler Walker met and married Alexander Dewson on September 19, 1833. He had a son Alexander, born about 1830, whom he brought to the new family.[5][6][nb 3] He was listed as a laborer in the city directory in 1837.[5][nb 4] They had a daughter, Margareta, who died at five months of age on April 11, 1837 of lung fever.[5]

By 1848 and at least through 1852, the Dewsons lived on 13 Southac Street.[7][8] Southac Street is not Phillips Street, located in Beacon Hill.[9][10] Alexander Dewson died at the age of 46 of consumption (tuberculosis) on May 3, 1851.[5]

Walker attended public schools in Charlestown, Massachusetts.[1][11]

Leatherwork

Walker received training in working with leather as a young man. He established a business that eventually employed 15 people.[1]

Abolitionist

Walker was an abolitionist who in 1851 collaborated with attorney Robert Morris and activist Lewis Hayden of the Boston Vigilance Committee to gain the release of Shadrach Minkins, a fugitive slave from Virginia who had been arrested in Boston by US Marshals under the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850. The men helped him hide and travel via the Underground Railroad to Canada, where he settled in Montreal. The men were "well-known Boston abolitionists" who were praised for their efforts to obtain Minkins' release.[1]

Marriage and children

Walker married Hannah Jane Van Vronker on November 15, 1858 in Boston. He was 28 and his bride was 23.[12] Hannah was born in Lowell on October 10, 1835,[13] one of Henry and Lucinda Webster Van Vronker’s three daughters.[12][14][nb 5]

The couple had a son named Edwin E. Walker about 1859 and a daughter Grace born about 1864. The family lived with Walker's mother, Eliza Dewson, also recorded as Susan, in Charlestown. Hannah is not living with the family by 1870.[15]

Lawyer

Having been inspired by Blackstone's Commentaries, Walker studied law at the Georgetown, Massachusetts office of Charles A. Tweed and John Q. A. Griffin. He studied while continuing to run his leatherwork business.[1][11][nb 6] He became the first (or third) black lawyer in the state of Massachusetts when he was admitted to the bar in May 1861 in Suffolk County.[1][11][3][nb 7] He was described as one of Boston's "prominent" attorneys.[16]

Massachusetts State Legislature

In 1866 Walker, representing Boston's Ward 3,[3] and Charles Lewis Mitchell (1829-1912) representing Ward 6, were the first black men elected to the Massachusetts State Legislature.[1][16] Both men were Republicans.[17] (Note: At one time Walker was thought to have been the first black elected to the state legislature, but documentation was found about Lewis' being elected the same year.)

On Tuesday, November 6, 1866, Claude August Crommelin remarked about the otherwise quiet election day:

Only the election of two colored men as representatives in the state legislature made some noise here and gave sufficient matter for conversation, as this is the first election of its kind. Messrs. Mitchell and Walker are the first of the 'despised race' who are called to post such as this one. And that a combination of circumstances has caused that Mr. Walker is representing Beacon Street and Commonwealth Avenue makes the case even more special.[18]

As the men began their one-year terms in 1867, the country was in the midst of Reconstruction following the end of the Civil War. In southern states, slaves were emancipated, laws were changed to allow African-American men to vote and hold public office, and states were drafting laws to begin providing equal rights to African-American people.[19]

During his term as a legislator, Walker opposed many of the approaches developed by fellow Republicans. In 1867 he was not renominated for a second term. He joined the Democratic Party, being one of many Boston African Americans to switch parties.[1][16]

Subsequent political career

Walker was nominated as a state judge by Democratic Governor Benjamin F. Butler at a time when the Republicans held a majority in the state legislature. They voted to give the position to George Lewis Ruffin, an African American considered by the Republicans to be "loyal" to their party. Walker was nominated for a position as judge three times by the governor but rejected by the legislature each time.[1]

In 1885 Walker, with wealthy restauranteur George T. Downing and other black leaders, formed the Negro Political Independence Movement. Walker was elected Colored National League president in 1890. He was nominated for president in 1896 by the Negro Party.[1]

Death

Walker died of pneumonia on January 13, 1901 in Boston.[1]

See also

- African-American officeholders in the United States, 1789-1866

Notes

- ↑ His mother may have been Emily[1] or Eliza, a runaway slave.[2] Another theory is that she was Eliza Butler, from a notable black family in Boston.[3]

- ↑ The Bench and Bar of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts stated that Walker was born in 1835.[7] If he was born in 1835, then David Walker would not have been his father, and this was 2 years after his mother's marriage to Alexander Dewson. Hinks further comments that this is not likely, because of the improbability of Edwin having taken the last name Walker if he was the son of Dewson.[4]

- ↑ Alexander had been left $1000 for the construction of a house from William H. Bordman, who had died on June 15, 1872. Since Alexander had died by this time, there was a question about whether Eliza, son Alexander and stepson Alexander were entitled to the inheritance. Further, whether Alexander is entitled to the entire portion, or if it should be split three ways. The case - John D. Bates & another, administrator, vs. Alexander Dewson, and others - was presented to the Massachusetts Supreme Court. It was decided that Alexander's family should inherit the money and that it should be split equally two ways: his wife Eliza and son Alexander.[6]

- ↑ Hinks says that Dewson (or Duson) was not in the city records after 1839.[4]

- ↑ The transcribed marriage record gives her last name as Van Kronker.[5]

- ↑ Davis said that he studied at Tweed's office in Boston.[7]

- ↑ Davis and Valle said that he was the first black to be admitted to the bar in the state; Black Past said he was the third.[2][7][8]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 1.6 1.7 1.8 1.9 1.10 1.11

- ↑ "David Walker, 1785-1830". University of North Carolina. Retrieved Retrieved April 22, 2013.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Paul Della Valle (13 January 2009). Massachusetts Troublemakers: Rebels, Reformers, and Radicals from the Bay State. Globe Pequot. p. 103. ISBN 978-0-7627-5795-4. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Peter Hinks (1997). To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren: David Walker and the Problem of Antebellum Slave Resistance. Penn State Press. pp. 77–. ISBN 978-0-271-04274-9. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Peter Hinks (30 January 1996). To Awaken My Afflicted Brethren: David Walker And the Problem of Antebellum Slave Resistance. Penn State Press. pp. 270–. ISBN 978-0-271-02927-6. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Massachusetts. Supreme Judicial Court (1881). Massachusetts Reports: Cases Argued and Determined in the Supreme Judicial Court of Massachusetts. H.O. Houghton and Company. pp. 334–35. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Alex Dewson ID #1717. Black Boston Database. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ The Boston Directory: ...including All Localities Within the City Limits, as Allston, Brighton, Charlestown, Dorchester, Hyde Park, Roslindale, Roxbury, West Roxbury. Sampson & Murdock Company. 1850. p. 317. Retrieved 24 April 2013.

- ↑ Black Heritage Trail: Lewis Hayden. Historic Buildings of Massachusetts. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ 13 Phillips (previously Southac) Street, Boston. Google maps. Retrieved April 24, 2013.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 Boston Marriages in 1858. Town and City Clerks of Massachusetts. Massachusetts Vital and Town Records. Provo, UT. p. 105.

- ↑ "Massachusetts, Births and Christenings, 1639-1915," index, FamilySearch (https://familysearch.org/pal:/MM9.1.1/FZ91-P72 : accessed 30 Nov 2013), Hannah Jane Van Vronker, 10 Oct 1835.

- ↑ Contee, Clarence G. Edwin G. Walker, Black Leader: Generally Acknowledged Son of David Walker, Negro History Bulletin, 39 (March 1976): 556-59.

- ↑ 1860 Charlestown, 1870 Charlestown and 1880 Boston, U.S. census, population schedule. NARA microfilm publication M653, 1,438 rolls. Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Alton Hornsby Jr. (31 August 2011). Black America: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia: A State-by-State Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 385. ISBN 978-1-57356-976-7. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ George Lowell Austin (1875). The History of Massachusetts: From the Landing of the Pilgrims to the Present Time. Including a Narrative of the Persecutions by State and Church in England; the Early Voyages to North America; the Explorations of the Early Settlers; Their Hardships, Sufferings and Conflicts with the Savages; the Rise of the Colonial Power; the Birth of Independence; the Formation of the Commonwealth; and the Gradual Progress of the State from Its Earliest Infancy to Its Present High Position. B.B. Russell. p. 530. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

- ↑ Claude August Crommelin (28 March 2011). A Young Dutchman Views Post--Civil War America: Diary of Claude August Crommelin. Indiana University Press. p. 83. ISBN 978-0-253-00090-3. Retrieved 22 April 2013.

- ↑ Charles W. Carey (1 January 2004). African-American Political Leaders. Infobase Publishing. p. vii. ISBN 978-1-4381-0780-6. Retrieved 23 April 2013.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

[[Category:Members of the Massachu setts House of Representatives]]