Edmonson sisters

Mary Edmonson (1832–1853) and Emily Edmonson (1835–1895), "two respectable young women of light complexion", were African Americans who became celebrities in the United States abolitionist movement after gaining their freedom from slavery. On April 15, 1848, they were among the seventy-seven slaves who tried to escape from Washington, DC on the schooner The Pearl to sail up the Chesapeake Bay to freedom in New Jersey.

Although that effort failed, they were freed from slavery by funds raised by the Congregational Church in Brooklyn, New York, whose pastor was Henry Ward Beecher, an abolitionist. After gaining freedom, the Edmonsons were supported to go to school; they also worked. They campaigned with Beecher throughout the North for the end of slavery in the United States.[1][2]

Early life

The Edmonson sisters were the daughters of Paul and Amelia Edmonson, a free black man and an enslaved woman in Montgomery County, Maryland. Mary and Emily were two of thirteen or fourteen children who survived to adulthood, all of whom were born into slavery. Since the 17th century, law common to all slave states decreed that the children of an enslaved mother inherited their mother's legal status, by the principle of partus sequitur ventrem.[3][4]

Their father, Paul Edmonson, was set free by his owner's will. Maryland was a state with a high percentage of free blacks. Most descended from slaves freed in the first two decades after the American Revolution, when slaveholders were encouraged to manumission by the principles of the war and activist Quaker and Methodist preachers. By 1810, more than 10 percent of blacks in the Upper South were free, with most of them in Maryland and Delaware.[5] By 1860, 49.7 percent of the blacks in Maryland were free.[6]

Edmonson purchased land in the Norbeck area of Montgomery County, where he farmed and established his family. Amelia was allowed to live with her husband, but continued to work for her master. The couple's children began work at an early age as servants, laborers and skilled workers. Beginning about age 13 or 14, they were "hired out" to work in elite private homes in nearby Washington, D.C. under a type of lease arrangement, where their wages went to the slaveholder.[3] This practice of "hiring out" grew from the shift away from the formerly labor-intensive tobacco plantation system, leaving planters in this part of the United States with surplus slaves. They hired out slaves or sold them to traders for the Deep South. Many slaves worked as servants in homes and hotels of the capital. Men were sometimes hired out as craftsmen, artisans or to work at the ports on the Potomac River.

By 1848 four of the older Edmonson sisters had bought their freedom (with the help of husbands and family), but the master had decided against allowing any more of the siblings to do so. Six were hired out for his benefit, including the two youngest sisters.[7]

Escape attempt

On April 15, 1848, the schooner Pearl docked at a Washington wharf. The Edmonson sisters and four of their brothers joined a large group of slaves (a total of 77) in an attempt to escape on the Pearl to freedom in New Jersey. Starting as a modest attempt of escape for seven slaves, the effort had been widely communicated and organized within the communities of free blacks and slaves, changing it to a major and unified effort, without the knowledge of the white organizers or crew. In 1848 free blacks outnumbered slaves in the District of Columbia by three to one; the community demonstrated it could act in a unified way.[8] Seventy-seven slaves boarded the Pearl, which was to sail down the Potomac River and up the Chesapeake Bay to the Chesapeake and Delaware Canal, from where they would travel up the Delaware River to freedom in New Jersey, a total of 225 miles. At the time, Emily was 13 years old and Mary was 15 or 16.[3]

The Pearl, with the fugitives hidden among boxes, began its way down the Potomac. It was delayed overnight by the shift in tides and then had to wait out rough weather from its anchor down the bay. In Washington the alarm was raised in the morning, as numerous slaveholders found their slaves had escaped. Historical accounts conflict and are not clear as to what details were known. Slaveholders put together an armed posse that went downriver on a steamboat. The steamboat caught up with the Pearl at Point Lookout, Maryland; and the posse seized it, towing the ship and its valuable cargo back to Washington, DC. If the posse had gone north to Baltimore, another likely escape route, the Pearl might have gotten away and reached its destination.[9]

When the Pearl arrived in Washington, a mob awaited the ship. Daniel Drayton and Edward Sayres, the two white captains, had to be taken into safety as pro-slavery people attacked them for threatening their control of property. The fugitive slaves were taken to a local jail. It was later reported that when somebody from the crowd asked the Edmonson girls if they were ashamed for what they had done, Emily replied proudly that they would do exactly the same thing again.[9] Three days of riots and disturbances followed, as pro-slavery agitators attacked anti-slavery offices and presses in the city in an attempt to suppress the abolitionist movement. Most of the masters of the fugitive slaves decided to sell them quickly to slave traders, rather than provide another chance to escape. Fifty of the slaves were transported by train to Baltimore, from where they were sold and transported to the Deep South.[9]

New Orleans

Despite Paul Edmonson's desperate efforts to delay the sale of his children so he could raise sufficient money to purchase their freedom, the slave trading partners Bruin & Hill from Alexandria, Virginia bought the six Edmonson siblings. Under inhumane conditions, the siblings were transported by ship to New Orleans. New Orleans was the largest slave market in the nation, and well known for selling "fancy girls" (pretty light-skinned enslaved young women) as sex slaves.[3][10]

Hamilton Edmonson, the eldest of the siblings, had already been living as a freeman for several years. He worked as a cooper. With the help of donations from a Methodist minister arranged by their father, Hamilton arranged for the purchase of his brother Samuel Edmonson by a prosperous New Orleans cotton merchant to work as his butler. When the merchant died in 1853, Samuel moved with that family and its other slaves to what is now the 1850 House in the Pontalba Buildings on Jackson Square.[3][11][12][13]

In New Orleans, the other siblings were forced to stay for days in an open porch facing the street waiting for buyers. The sisters were handled brusquely and exposed to obscene comments. Before the family could rescue the remainder of its members, a yellow fever epidemic erupted in New Orleans. The slave traders transported the Edmonson sisters back to Alexandria as a measure to protect their investments.[3][12]

Ephraim Edmonson and John Edmonson, two other brothers who had tried to escape on the Pearl, were kept in New Orleans. Their brother Hamilton worked for and eventually obtained their purchase and freedom.[12]

Henry Ward Beecher

In Alexandria, the Edmonson sisters were hired out to do laundering, ironing and sewing, with wages going to the slave traders. They were locked up at night. Paul Edmonson continued his campaign to free his daughters while Bruin & Hill demanded $2,250 for their release.[3]

With letters from Washington-area supporters, Paul Edmonson met Henry Ward Beecher, a young Congregationalist preacher with a church in Brooklyn, New York who was known to support abolitionism. Beecher's church members raised the funds to purchase the Edmonson sisters and give them freedom. Accompanied by William Chaplin, a white abolitionist who had helped pay for the Pearl for the escape attempt, Beecher went to Washington to arrange the transaction.[3]

Mary Edmonson and Emily Edmonson were emancipated on November 4, 1848. The family gathered for a celebration at another sister's house in Washington. Beecher's church continued to contribute money to send the sisters to school for their education. They first enrolled at New York Central College, an interracial institution in Cortland, New York. They also worked as cleaning servants to support themselves.[3]

While studying, the sisters participated in anti-slavery rallies around New York state. The story of their slavery, escape attempt, and suffering was often repeated. Beecher's son and biographer recorded that "this case at the time attracted wide attention."[1][3] At the rallies, the Edmonson sisters participated in mock slave auctions designed by Beecher to attract publicity to the abolitionist cause. In describing the role that women such as the Edmonson sisters played in such well-publicized political theater, a scholar at the University of Maryland asserted in 2002:

| “ | Beecher staged his most successful auctions using attractive mulatto women or female children (such as the Edmonson sisters, or the beautiful little girl, Pinky, who, according to Beecher, "No one would know from a white child"), making a material choice in "casting" his political protest that was calculated to arouse the audience's interest. As he displayed the women's bodies on the stage, Beecher exhorted his audience to imagine the fate that awaited these young women, or "marketable commodities", as he termed them, in the fancy girl auctions of New Orleans. His casting choices could only work with beautiful, fair-skinned women.[10] | ” |

Fugitive Slave Law convention

In summer 1850, the Edmonson sisters attended the Slave Law Convention, an anti-slavery meeting in Cazenovia, New York organized by local abolitionist Theodore Dwight Weld and others, to demonstrate against the Fugitive Slave Act soon to be passed by the U.S. Congress. Under this act, slave owners had powers to arrest fugitive slaves in the North. The convention declared all slaves to be prisoners of war and warned the nation of an unavoidable insurrection of slaves unless they were emancipated.[3][14]

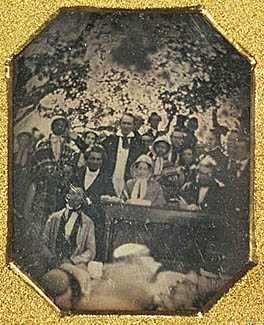

At this convention, the sisters were included in a historic daguerreotype photograph taken by Theodore Dwight Weld's brother, Ezra Greenleaf Weld. Also included in the picture are abolitionist Abby Kelley Foster and the legendary orator Frederick Douglass.[3][14][15]

While there were many slaves "whom it was impossible to tell from a white", the Edmonson sisters' mixed-race appearance may have well suited their role as two of the "public faces" of American slavery.[1]

Oberlin College

In 1853, the Edmonson sisters attended the Young Ladies Preparatory School at Oberlin College in Ohio through the support of Beecher and his sister, Harriet Beecher Stowe, author of Uncle Tom's Cabin. Since its founding in the 1830s, the school had admitted blacks as well as whites, and was a center of abolitionist activism. Six months after arriving at Oberlin, Mary Edmonson died of tuberculosis.[3]

That same year, Stowe included part of the Edmonson sisters' history with other factual accounts of slavery experiences in A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin.[3]

Normal School for Colored Girls

Eighteen-year-old Emily returned to Washington with her father, where she enrolled in the Normal School for Colored Girls. Located near the current Dupont Circle, the school trained young African-American women to become teachers. For protection, the Edmonson family moved to a cabin on the grounds. Emily and Myrtilla Miner, the founder of the school, learned to shoot.[3]

Later life

At age 25 in 1860, Emily Edmonson married Larkin Johnson. They returned to the Sandy Spring, Maryland area and lived there for twelve years before moving to Anacostia in Washington, DC. There they purchased land and became founding members of the Hillsdale community. At least one of their children was born in Montgomery County before their move to Anacostia.[3] Edmonson maintained her relationship with fellow Anacostia resident Frederick Douglass, and both continued working in the abolitionist movement. Even after the ratification of the 13th Amendment, they remained so close that Emily's granddaughters observed that they were like "brother and sister." Emily Edmonson Johnson died at her home on September 15, 1895.[3]

Legacy and honors

- 2010, the city of Alexandria, Virginia named a park on Duke Street as Edmonson Plaza after the two sisters. It is near a former slave trader's facility and other historical sites associated with slavery.

- 2010, a 10-foot-tall (3.0 m) bronze sculpture of the two sisters by the sculptor Erik Blome was installed at Edmonson Plaza at 1701 Duke Street in Alexandria, Virginia, next to the site that was Bruin & Hill's slave holding facility (now a private office).[16]

Other representation

- 1992, Judlyne A. Lilly's play, The Pearl, was given its première by The Source Theatre in Washington, D.C.; it was adapted from Paynter's 1930 book on the events.[8]

See also

References and notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "White Slaves". The Multiracial Activist. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ "Syracuse and the Underground Railroad, An exhibition of the Special Collections Research Center". Syracuse University Library. 2005-09-30. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 3.11 3.12 3.13 3.14 3.15 3.16 "Women's History Archives". Montgomery County Commission for Women Counseling & Career Center. Retrieved 2007-01-06.; Harriet Beecher Stowe, A Key to Uncle Tom's Cabin, (1852); John H. Paynter, Fugitives of the Pearl, Washington D.C.: Associated Publishers (1930); and Mary Kay Ricks, "A Passage to Freedom", Washington Post Magazine (February 17, 2002): 21-36

- ↑ ", Mary and Emily Edmonson". The Sojourn Journals. potomacheritage.org. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, p. 81

- ↑ Peter Kolchin, American Slavery: 1619-1877, New York: Hill and Wang, p. 82

- ↑ Mary Kay Ricks, Escape on the Pearl: The Heroic Bid for Freedom on the Underground Railroad (HarperCollins Publishers, January 2007) ISBN 0-06-078660-4,

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Mary Beth Corrigan, "The Legacy and Significance of a Failed Mass Slave Escape", H-Net Reviews: Josephine Pacheco, The Pearl: A Failed Slave Escape on the Potomac, April 2006, accessed 12 Jan 2009

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 [Josephine F. Pacheco, The Pearl], Raleigh, NC: University of North Carolina Press, 2005, pp.57-58, accessed 12 Jan 2009

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Nathans, Heather S. (University of Maryland) (16 November 2002). "Casting the Civil War: The "Slave Auctions" of Henry Ward Beecher",". Seminar Abstracts. ASTR Conference. Archived from the original on 2006-08-13. Retrieved 2007-01-07.

- ↑ "Dilapidated to Elegant" _Louisiana Cultural Vistas_ Fall 2001, pp.9-10

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 "Daily Journals". Potomac Sojourn 2001. Potomac Heritage Partnership. 2001. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Samuel Edmonson never abandoned his pursuit of freedom. In 1859 he escaped on a ship to Jamaica. From there he went on to Liverpool and, with his wife and child, sailed to a new life in Australia.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Weiskotten, Daniel H. (2003-05-25). ""Great Cazenovia Fugitive Slave Law Convention" at Cazenovia, NY, August 21 and 22, 1850". rootsweb.com. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ "Fugitive Slave Law Convention, Cazenovia, New York". J. Paul Getty Museum. Retrieved 2007-01-06.

- ↑ Danforth, Austin. "Slavery and Freedom, Embodied," The Alexandria Times, 27 May 2010

Additional reading

- Debby Applegate, The Most Famous Man in America: The Biography of Henry Ward Beecher (Doubleday, June 2006) ISBN 0-385-51397-6

- Stanley Harrold, Subversives: Antislavery Community in Washington, D.C., 1828-1865 (Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 2003)

- Mary Kay Ricks, "A Passage to Freedom," Washington Post Magazine (February 17, 2002)

- Hilary Russell, "Underground Railroad Activists in Washington, D.C.", Washington History 13. no. 2 (Fall/Winter 2002): pp. 38–39.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||