History of China

Chinese civilization originated in various regional centers along both the Yellow River and the Yangtze River valleys in the Neolithic era, but the Yellow River is said to be the cradle of Chinese civilization. With thousands of years of continuous history, China is one of the world's oldest civilizations.[1] The written history of China can be found as early as the Shang Dynasty (c. 1700–1046 BC),[2] although ancient historical texts such as the Records of the Grand Historian (ca. 100 BC) and Bamboo Annals assert the existence of a Xia Dynasty before the Shang.[2][3] Much of Chinese culture, literature and philosophy further developed during the Zhou Dynasty (1045–256 BC).

The Zhou Dynasty began to bow to external and internal pressures in the 8th century BC, and the kingdom eventually broke apart into smaller states, beginning in the Spring and Autumn Period and reaching full expression in the Warring States period. This is one of multiple periods of failed statehood in Chinese history (the most recent of which was the Chinese Civil War).

In between eras of multiple kingdoms and warlordism, Chinese dynasties have ruled parts or all of China; in some eras, including the present, control has stretched as far as Xinjiang and/or Tibet. This practice began with the Qin Dynasty: in 221 BC, Qin Shi Huang united the various warring kingdoms and created the first Chinese empire. Successive dynasties in Chinese history developed bureaucratic systems that enabled the Emperor of China to directly control vast territories. China's last dynasty was Qing, which was replaced by the Republic of China in 1912, and in the mainland by the People's Republic of China in 1949.

The conventional view of Chinese history is that of alternating periods of political unity and disunity, with China occasionally being dominated by steppe peoples, most of whom were in turn assimilated into the Han Chinese population. Cultural and political influences from other parts of Asia and the Western world, carried by successive waves of immigration, expansion, foreign contact, and cultural assimilation are part of the modern culture of China.

Prehistory

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleolithic

What is now China was inhabited by Homo erectus more than a million years ago.[4] Recent study shows that the stone tools found at Xiaochangliang site are magnetostratigraphically dated to 1.36 million years ago.[5] The archaeological site of Xihoudu in Shanxi Province is the earliest recorded use of fire by Homo erectus, which is dated 1.27 million years ago.[4] The excavations at Yuanmou and later Lantian show early habitation. Perhaps the most famous specimen of Homo erectus found in China is the so-called Peking Man discovered in 1923–27.

Neolithic

The Neolithic age in China can be traced back to about 10,000 BC.[6]

Early evidence for proto-Chinese millet agriculture is radiocarbon-dated to about 7000 BC.[7] Farming gave rise to the Jiahu culture (7000 to 5800 BC). At Damaidi in Ningxia, 3,172 cliff carvings dating to 6000–5000 BC have been discovered, "featuring 8,453 individual characters such as the sun, moon, stars, gods and scenes of hunting or grazing." These pictographs are reputed to be similar to the earliest characters confirmed to be written Chinese.[8][9] Excavation of a Peiligang culture site in Xinzheng county, Henan, found a community that flourished in 5,500–4,900 BC, with evidence of agriculture, constructed buildings, pottery, and burial of the dead.[10] With agriculture came increased population, the ability to store and redistribute crops, and the potential to support specialist craftsmen and administrators.[11] In late Neolithic times, the Yellow River valley began to establish itself as a center of Yangshao culture (5000 BC to 3000 BC), and the first villages were founded; the most archaeologically significant of these was found at Banpo, Xi'an.[12] Later, Yangshao culture was superseded by the Longshan culture, which was also centered on the Yellow River from about 3000 BC to 2000 BC.

The early history of China is obscured by the lack of written documents from this period, coupled with the existence of later accounts that attempted to describe events that had occurred several centuries previously. In a sense, the problem stems from centuries of introspection on the part of the Chinese people, which has blurred the distinction between fact and fiction in regards to this early history.

Ancient China

Xia Dynasty (c. 2100 – c. 1600 BC)

The Xia Dynasty of China (from c. 2100 to c. 1600 BC) is the first dynasty to be described in ancient historical records such as Sima Qian's Records of the Grand Historian and Bamboo Annals.[2][3]

Although there is disagreement as to whether the dynasty actually existed, there is some archaeological evidence pointing to its possible existence. Sima Qian, writing in the late 2nd century BC, dated the founding of the Xia Dynasty to around 2200 BC, but this date has not been corroborated. Most archaeologists now connect the Xia to excavations at Erlitou in central Henan province,[13] where a bronze smelter from around 2000 BC was unearthed. Early markings from this period found on pottery and shells are thought to be ancestral to modern Chinese characters.[14] With few clear records matching the Shang oracle bones or the Zhou bronze vessel writings, the Xia era remains poorly understood.

According to mythology, the dynasty ended around 1600 BC as a consequence of the Battle of Mingtiao.

Shang Dynasty (c. 1700–1046 BC)

Capital: Yin, near Anyang (Shang Dynasty period)

Archaeological findings providing evidence for the existence of the Shang Dynasty, c. 1600–1046 BC, are divided into two sets. The first set – from the earlier Shang period – comes from sources at Erligang, Zhengzhou, and Shangcheng. The second set – from the later Shang or Yin (殷) period – is at Anyang, in modern-day Henan, which has been confirmed as the last of the Shang's nine capitals (c. 1300–1046 BC).[citation needed] The findings at Anyang include the earliest written record of Chinese past so far discovered: inscriptions of divination records in ancient Chinese writing on the bones or shells of animals – the so-called "oracle bones", dating from around 1200 BC.[15]

The Shang Dynasty featured 31 kings, from Tang of Shang to King Zhou of Shang. In this period, the Chinese worshipped many different gods – weather gods and sky gods – and also a supreme god, named Shangdi, who ruled over the other gods. Those who lived during the Shang Dynasty also believed that their ancestors – their parents and grandparents – became like gods when they died, and that their ancestors wanted to be worshipped, too, like gods. Each family worshipped its own ancestors.

The Records of the Grand Historian states that the Shang Dynasty moved its capital six times. The final (and most important) move to Yin in 1350 BC led to the dynasty's golden age. The term Yin Dynasty has been synonymous with the Shang dynasty in history, although it has lately been used to specifically refer to the latter half of the Shang Dynasty.

Chinese historians living in later periods were accustomed to the notion of one dynasty succeeding another, but the actual political situation in early China is known to have been much more complicated. Hence, as some scholars of China suggest, the Xia and the Shang can possibly refer to political entities that existed concurrently, just as the early Zhou is known to have existed at the same time as the Shang.

Although written records found at Anyang confirm the existence of the Shang dynasty,[citation needed] Western scholars are often hesitant to associate settlements that are contemporaneous with the Anyang settlement with the Shang dynasty. For example, archaeological findings at Sanxingdui suggest a technologically advanced civilization culturally unlike Anyang. The evidence is inconclusive in proving how far the Shang realm extended from Anyang. The leading hypothesis is that Anyang, ruled by the same Shang in the official history, coexisted and traded with numerous other culturally diverse settlements in the area that is now referred to as China proper.

Zhou Dynasty (1046–256 BC)

The Zhou Dynasty was the longest-lasting dynasty in Chinese history, from 1066 BC to approximately 256 BC. By the end of the 2nd millennium BC, the Zhou Dynasty began to emerge in the Yellow River valley, overrunning the territory of the Shang. The Zhou appeared to have begun their rule under a semi-feudal system. The Zhou lived west of the Shang, and the Zhou leader had been appointed "Western Protector" by the Shang. The ruler of the Zhou, King Wu, with the assistance of his brother, the Duke of Zhou, as regent, managed to defeat the Shang at the Battle of Muye.

The king of Zhou at this time invoked the concept of the Mandate of Heaven to legitimize his rule, a concept that would be influential for almost every succeeding dynasty. Like Shangdi, Heaven (tian) ruled over all the other gods, and it decided who would rule China. It was believed that a ruler had lost the Mandate of Heaven when natural disasters occurred in great number, and when, more realistically, the sovereign had apparently lost his concern for the people. In response, the royal house would be overthrown, and a new house would rule, having been granted the Mandate of Heaven.

The Zhou initially moved their capital west to an area near modern Xi'an, on the Wei River, a tributary of the Yellow River, but they would preside over a series of expansions into the Yangtze River valley. This would be the first of many population migrations from north to south in Chinese history.

Spring and Autumn Period (722–476 BC)

Capitals: of the State of Yan, Beijing; of the State of Qin, Xi'an

In the 8th century BC, power became decentralized during the Spring and Autumn period, named after the influential Spring and Autumn Annals. In this period, local military leaders used by the Zhou began to assert their power and vie for hegemony. The situation was aggravated by the invasion of other peoples from the northwest, such as the Qin, forcing the Zhou to move their capital east to Luoyang. This marks the second major phase of the Zhou dynasty: the Eastern Zhou. The Spring and Autumn Period is marked by a falling apart of the central Zhou power. In each of the hundreds of states that eventually arose, local strongmen held most of the political power and continued their subservience to the Zhou kings in name only. Some local leaders even started using royal titles for themselves. China now consisted of hundreds of states, some of them only as large as a village with a fort.

The Hundred Schools of Thought of Chinese philosophy blossomed during this period, and such influential intellectual movements as Confucianism, Taoism, Legalism and Mohism were founded, partly in response to the changing political world.

Warring States Period (476–221 BC)

Several capitals, due to there being multiple states

After further political consolidation, seven prominent states remained by the end of 5th century BC, and the years in which these few states battled each other are known as the Warring States period. Though there remained a nominal Zhou king until 256 BC, he was largely a figurehead and held little real power.

As neighboring territories of these warring states, including areas of modern Sichuan and Liaoning, were annexed, they were governed under the new local administrative system of commandery and prefecture (郡縣/郡县). This system had been in use since the Spring and Autumn Period, and parts can still be seen in the modern system of Sheng & Xian (province and county, 省縣/省县).

The final expansion in this period began during the reign of Ying Zheng, the king of Qin. His unification of the other six powers, and further annexations in the modern regions of Zhejiang, Fujian, Guangdong and Guangxi in 214 BC, enabled him to proclaim himself the First Emperor (Qin Shi Huang).

Imperial China

Qin Dynasty (221–206 BC)

Capital: Xianyang Historians often refer to the period from Qin Dynasty to the end of Qing Dynasty as Imperial China. Though the unified reign of the First Qin Emperor lasted only 12 years, he managed to subdue great parts of what constitutes the core of the Han Chinese homeland and to unite them under a tightly centralized Legalist government seated at Xianyang (close to modern Xi'an). The doctrine of Legalism that guided the Qin emphasized strict adherence to a legal code and the absolute power of the emperor. This philosophy, while effective for expanding the empire in a military fashion, proved unworkable for governing it in peacetime. The Qin Emperor presided over the brutal silencing of political opposition, including the event known as the burning of books and burying of scholars. This would be the impetus behind the later Han synthesis incorporating the more moderate schools of political governance.

The Qin Dynasty is well known for beginning the Great Wall of China, which was later augmented and enhanced during the Ming Dynasty. The other major contributions of the Qin include the concept of a centralized government, the unification of the legal code, development of the written language, measurement, and currency of China after the tribulations of the Spring and Autumn and Warring States Periods. Even something as basic as the length of axles for carts had to be made uniform to ensure a viable trading system throughout the empire.

Han Dynasty (202 BC–AD 220)

Capitals: Chang'an, Luoyang, Liyang, Xuchang

Western Han

The Han Dynasty was founded by Liu Bang, who emerged victorious in the civil war that followed the collapse of the unified but short-lived Qin Dynasty. A golden age in Chinese history, the Han Dynasty's long period of stability and prosperity consolidated the foundation of China as a unified state under a central imperial bureaucracy, which was to last intermittently for most of the next two millennium. During the Han Dynasty, territory of China was extended to most of the China proper and to areas far west. Confucianism was officially elevated to orthodox status and was to shape the subsequent Chinese Civilization. Art, Culture and Science all advanced to unprecedented heights. With the profound and lasting impacts of this period of Chinese history, the dynasty name "Han" had been taken as the name of the Chinese people, now the dominant ethnic group in modern China, and had been commonly used to refer to Chinese language and written characters.

After the initial Laissez-faire policies of Emperors Wen and Jing, the ambitious Emperor Wu brought the empire to its zenith. To consolidate his power, Confucianism, which emphasizes stability and order in a well-structured society, was given exclusive patronage to be the guiding philosophical thoughts and moral principles of the empire. Imperial Universities were established to support its study and further development, while other schools of thoughts were discouraged.

Major military campaigns were launched to weaken the nomadic Xiongnu Empire, limiting their influence north of the Great Wall. Along with the diplomatic efforts led by Zhang Qian, the sphere of influence of the Han Empire extended to the states in the Tarim Basin, opened up the Silk Road that connected China to west, stimulating prosperous bilateral trades and cultural exchange. To the south, various small kingdoms far beyond the Yangtze River Valley were formally incorporated into the empire.

Emperor Wu also dispatched a series of military campaigns against the Baiyue tribes. The Han annexed Minyue in 135 BC and 111 BC, Nanyue in 111 BC, and Dian in 109 BC.[16] Migration and military expeditions led to the cultural assimilation of the south.[17] It also brought the Han into contact with kingdoms in Southeast Asia, introducing diplomacy and trade.[18]

After Emperor Wu, the empire slipped into gradual stagnation and decline. Economically, the state treasury was strained by excessive campaigns and projects, while land acquisitions by elite families gradually drained the tax base. Various consort clans exerted increasing control over strings of incompetent emperors and eventually the dynasty was briefly interrupted by the usurpation of Wang Mang.

Xin Dynasty

In AD 9, the usurper Wang Mang claimed that the Mandate of Heaven called for the end of the Han dynasty and the rise of his own, and he founded the short-lived Xin ("New") Dynasty. Wang Mang started an extensive program of land and other economic reforms, including the outlawing of slavery and land nationalization and redistribution. These programs, however, were never supported by the landholding families, because they favored the peasants. The instability of power brought about chaos, uprisings, and loss of territories. This was compounded by mass flooding of the Yellow River; silt buildup caused it to split into two channels and displaced large numbers of farmers. Wang Mang was eventually killed in Weiyang Palace by an enraged peasant mob in AD 23.

Eastern Han

Emperor Guangwu reinstated the Han Dynasty with the support of landholding and merchant families at Luoyang, east of the former capital Xi'an. Thus, this new era is termed the Eastern Han Dynasty. With the capable administrations of Emperors Ming and Zhang, former glories of the dynasty was reclaimed, with brilliant military and cultural achievements. The Xiongnu Empire was decisively defeated. The diplomat and general Ban Chao further expanded the conquests across the Pamirs to the shores of the Caspian Sea,[19] thus reopening the Silk Road, and bringing trade, foreign cultures, along with the arrival of Buddhism. With extensive connections with the west, the first of several Roman embassies to China were recorded in Chinese sources, coming from the sea route in AD 166, and a second one in AD 284.

The Eastern Han Dynasty was one of the most prolific era of science and technology in ancient China, notably the historic invention of papermaking by Cai Lun, and the numerous contributions by the polymath Zhang Heng.

By the 2nd century, the empire declined amidst land acquisitions, invasions, and feuding between consort clans and eunuchs. The Yellow Turban Rebellion broke out in AD 184, ushering in an era of warlords. In the ensuing turmoil, three states tried to gain predominance in the period of the Three Kingdoms. This time period has been greatly romanticized in works such as Romance of the Three Kingdoms.

Wei and Jin Period (AD 265–420)

Capitals: of Cao Wei and Western Jin, Luoyang; of Shu Han, Chengdu; of Eastern Wu and Eastern Jin, Jiankang; of Western Jin, Chang'an

After Cao Cao reunified the north in 208, his son proclaimed the Wei dynasty in 220. Soon, Wei's rivals Shu and Wu proclaimed their independence, leading China into the Three Kingdoms Period. This period was characterized by a gradual decentralization of the state that had existed during the Qin and Han dynasties, and an increase in the power of great families. Although the Three Kingdoms were reunified by the Jin Dynasty in 280, this structure was essentially the same until the Wu Hu uprising.

Wu Hu Period (AD 304–439)

Several capitals, due to there being several states and warring

Taking advantage of civil war in the Jin Dynasty, the contemporary non-Han Chinese (Wu Hu) ethnic groups controlled much of the country in the early 4th century and provoked large-scale Han Chinese migrations to south of the Yangtze River. In 303 the Di people rebelled and later captured Chengdu, establishing the state of Cheng Han. Under Liu Yuan, the Xiongnu rebelled near today's Linfen County and established the state of Han Zhao. Liu Yuan's successor Liu Cong captured and executed the last two Western Jin emperors. Sixteen kingdoms were a plethora of short-lived non-Chinese dynasties that came to rule the whole or parts of northern China in the 4th and 5th centuries. Many ethnic groups were involved, including ancestors of the Turks, Mongols, and Tibetans. Most of these nomadic peoples had, to some extent, been "sinicized" long before their ascent to power. In fact, some of them, notably the Qiang and the Xiongnu, had already been allowed to live in the frontier regions within the Great Wall since late Han times.

Southern and Northern Dynasties (AD 420–589)

Capitals: of the Northern Dynasties: Ye, Chang'an, of the Southern Dynasties: Jiankang

Signaled by the collapse of East Jin Dynasty in 420, China entered the era of the Southern and Northern Dynasties. The Han people managed to survive the military attacks from the nomadic tribes of the north, such as the Xianbei, and their civilization continued to thrive.

In southern China, fierce debates about whether Buddhism should be allowed to exist were held frequently by the royal court and nobles. Finally, near the end of the Southern and Northern Dynasties era, both Buddhist and Taoist followers compromised and became more tolerant of each other.

In 589, Sui annexed the last Southern Dynasty, Chen, through military force, and put an end to the era of Southern and Northern Dynasties.

Sui Dynasty (AD 589–618)

Official capital: Daxing; secondary capital: Dongdu

The Sui Dynasty, which managed to reunite the country in 589 after nearly four centuries of political fragmentation, played a role more important than its length of existence would suggest. The Sui brought China together again and set up many institutions that were to be adopted by their successors, the Tang. These included the government system of Three Departments and Six Ministries, standard coinage, improved defense and expansion of the Great Wall, and official support for Buddhism. Like the Qin, however, the Sui overused their resources and collapsed.

Tang Dynasty (AD 618–907)

Capitals: Chang'an and Luoyang

Tang Dynasty was founded by Emperor Gaozu on 18 June 618. It was a golden age of Chinese civilization with significant developments in art, literature, particularly poetry, and technology. Buddhism became the predominant religion for common people. Chang'an (modern Xi'an), the national capital, was the largest city in the world of its time.

Started by the second emperor, Taizong, military campaigns were launched to dissolve threats from nomadic tribes, extend the border, and submit neighboring states into a tributary system. Military victories in the Tarim Basin kept the Silk Road open, connecting Chang'an to Central Asia and areas far to the west. In the south, lucrative maritime trade routes began from port cities such as Guangzhou. There was extensive trade with distant foreign countries, and many foreign merchants settled in China, boosting a vibrant cosmopolitan culture. The Tang culture and social systems were admired and adapted by neighboring countries like Japan. Internally, the Grand Canal linked the political heartland in Chang'an to the economic and agricultural centers in the eastern and southern parts of the empire.

Underlying the prosperity of the early Tang Dynasty was a strong centralized bureaucracy with efficient policies. The government was organized as "Three Departments and Six Ministries" to separately draft, review, and implement policies. These departments were run by royal family members as well as scholar officials who were selected from imperial examinations. These practices, which matured in the Tang Dynasty, were to be inherited by the later dynasties with some modifications.

The Tang land policy – the "Equal-field system" – claimed all lands as imperially owned, and were granted evenly to people according to the size of the households. The associated military policy – the "Fubing system" – conscripted all men in the nation for a fixed duty period each year in exchange for their land rights. These policies stimulated rapid growth of productivity, while boosting the army without much burden on the state treasury. However, lands gradually fell into the hands of private land owners, and standing armies were to replace conscription towards the middle period of the dynasty.

The dynasty continued to flourish under Empress Wu Zetian, the only empress regnant in Chinese history, and reached its zenith during the reign of Emperor Xuanzong, who oversaw an empire that stretched from the Pacific to the Aral Sea with at least 50 million people.

At the zenith of prosperity of the empire, the An Lushan Rebellion from 755 to 763 was a watershed event that devastated the population and drastically weakened the central imperial government. Regional military governors, known as Jiedushi, gained increasingly autonomous status while formerly submissive states raided the empire. Nevertheless, after the An Lushan Rebellion, the Tang civil society recovered and thrived amidst the weakened imperial bureaucracy.

From about 860, the Tang Dynasty declined due to a series of rebellions within China itself and in the former subject Kingdom of Nanzhao to the south. One warlord, Huang Chao, captured Guangzhou in 879, killing most of the 200,000 inhabitants, including most of the large colony of foreign merchant families there.[20][21] In late 880, Luoyang surrendered to Huang Chao, and on 5 January 881 he conquered Chang'an. The emperor Xizong fled to Chengdu, and Huang established a new temporary regime which was eventually destroyed by Tang forces. Another time of political chaos followed.

Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms (AD 907–960)

Various capitals

The period of political disunity between the Tang and the Song, known as the Five Dynasties and Ten Kingdoms period, lasted little more than half a century, from 907 to 960. During this brief era, when China was in all respects a multi-state system, five regimes rapidly succeeded one another in control of the old Imperial heartland in northern China. During this same time, sections of southern and western China were occupied by ten, more stable, regimes so the period is also referred to as the Ten Kingdoms.

Song, Liao, Jin, and Western Xia Dynasties (AD 960–1234)

Capitals: of the Song Dynasty, Kaifeng and Lin'an; of the Liao Dynasty, Shangjing, Nanjing, and Tokmok; of the Jin Dynasty, Shangjing, Zhongdu, and Kaifeng; of the Western Xia Dynasty, Yinchuan

In 960, the Song Dynasty gained power over most of China and established its capital in Kaifeng (later known as Bianjing), starting a period of economic prosperity, while the Khitan Liao Dynasty ruled over Manchuria, present-day Mongolia, and parts of Northern China. In 1115, the Jurchen Jin Dynasty emerged to prominence, annihilating the Liao Dynasty in 10 years. Meanwhile, in what are now the northwestern Chinese provinces of Gansu, Shaanxi, and Ningxia, there emerged a Western Xia Dynasty from 1032 to 1227, established by Tangut tribes.

The Jin Dynasty took power and conquered northern China in the Jin–Song Wars, capturing Kaifeng from the Song Dynasty, which moved its capital to Hangzhou (杭州). The Southern Song Dynasty also suffered the humiliation of having to acknowledge the Jin Dynasty as formal overlords. In the ensuing years, China was divided between the Song Dynasty, the Jin Dynasty and the Tangut Western Xia. Southern Song experienced a period of great technological development which can be explained in part by the military pressure that it felt from the north. This included the use of gunpowder weapons, which played a large role in the Song Dynasty naval victories against the Jin in the Battle of Tangdao and Battle of Caishi on the Yangtze River in 1161. Furthermore, China's first permanent standing navy was assembled and provided an admiral's office at Dinghai in 1132, under the reign of Emperor Renzong of Song.

The Song Dynasty is considered by many to be classical China's high point in science and technology, with innovative scholar-officials such as Su Song (1020–1101) and Shen Kuo (1031–1095). There was court intrigue between the political rivals of the Reformers and Conservatives, led by the chancellors Wang Anshi and Sima Guang, respectively. By the mid-to-late 13th century, the Chinese had adopted the dogma of Neo-Confucian philosophy formulated by Zhu Xi. Enormous literary works were compiled during the Song Dynasty, such as the historical work of the Zizhi Tongjian ("Comprehensive Mirror to Aid in Government"). Culture and the arts flourished, with grandiose artworks such as Along the River During the Qingming Festival and Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute, along with great Buddhist painters like the prolific Lin Tinggui.

Yuan Dynasty (AD 1271–1368)

The Jurchen-founded Jin Dynasty was defeated by the Mongols, who then proceeded to defeat the Southern Song in a long and bloody war, the first war in which firearms played an important role. During the era after the war, later called the Pax Mongolica, adventurous Westerners such as Marco Polo travelled all the way to China and brought the first reports of its wonders to Europe. In the Yuan Dynasty, the Mongols were divided between those who wanted to remain based in the steppes and those who wished to adopt the customs of the Chinese.

Kublai Khan, grandson of Genghis Khan, wanting to adopt the customs of China, established the Yuan Dynasty. This was the first dynasty to rule the whole of China from Beijing as the capital. Beijing had been ceded to Liao in AD 938 with the Sixteen Prefectures of Yan Yun. Before that, it had been the capital of the Jin, who did not rule all of China.

Before the Mongol invasion, Chinese dynasties reportedly had approximately 120 million inhabitants; after the conquest was completed in 1279, the 1300 census reported roughly 60 million people.[22] While it is tempting to attribute this major decline solely to Mongol ferocity, scholars today have mixed sentiments regarding this subject. Scholars such as Frederick W. Mote argue that the wide drop in numbers reflects an administrative failure to record rather than an actual decrease; others such as Timothy Brook argue that the Mongols created a system of enserfment among a huge portion of the Chinese populace, causing many to disappear from the census altogether; other historians like William McNeill and David Morgan argue that the Bubonic Plague was the main factor behind the demographic decline during this period.

In the 14th century, China suffered additional depredations from epidemics of plague. The Black Death is estimated to have killed 25 million people or 30% of the population of China.[23]

Ming Dynasty (AD 1368–1644)

Capitals: Nanjing, Beijing, Fuzhou, and Zhaoqing

Throughout the Yuan Dynasty, which lasted less than a century, there was relatively strong sentiment among the populace against the Mongol rule. The frequent natural disasters since the 1340s finally led to peasant revolts. The Yuan Dynasty was eventually overthrown by the Ming Dynasty in 1368.

Urbanization increased as the population grew and as the division of labor grew more complex. Large urban centers, such as Nanjing and Beijing, also contributed to the growth of private industry. In particular, small-scale industries grew up, often specializing in paper, silk, cotton, and porcelain goods. For the most part, however, relatively small urban centers with markets proliferated around the country. Town markets mainly traded food, with some necessary manufactures such as pins or oil.

Despite the xenophobia and intellectual introspection characteristic of the increasingly popular new school of neo-Confucianism, China under the early Ming Dynasty was not isolated. Foreign trade and other contacts with the outside world, particularly Japan, increased considerably. Chinese merchants explored all of the Indian Ocean, reaching East Africa with the voyages of Zheng He.

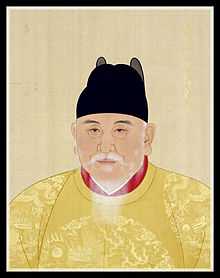

Zhu Yuanzhang or Hong-wu, the founder of the dynasty, laid the foundations for a state interested less in commerce and more in extracting revenues from the agricultural sector. Perhaps because of the Emperor's background as a peasant, the Ming economic system emphasized agriculture, unlike that of the Song and the Mongolian Dynasties, which relied on traders and merchants for revenue. Neo-feudal landholdings of the Song and Mongol periods were expropriated by the Ming rulers. Land estates were confiscated by the government, fragmented, and rented out. Private slavery was forbidden. Consequently, after the death of Emperor Yong-le, independent peasant landholders predominated in Chinese agriculture. These laws might have paved the way to removing the worst of the poverty during the previous regimes.

The dynasty had a strong and complex central government that unified and controlled the empire. The emperor's role became more autocratic, although Zhu Yuanzhang necessarily continued to use what he called the "Grand Secretaries" (内阁) to assist with the immense paperwork of the bureaucracy, including memorials (petitions and recommendations to the throne), imperial edicts in reply, reports of various kinds, and tax records. It was this same bureaucracy that later prevented the Ming government from being able to adapt to changes in society, and eventually led to its decline.

The Yong-le Emperor strenuously tried to extend China's influence beyond its borders by demanding other rulers send ambassadors to China to present tribute. A large navy was built, including four-masted ships displacing 1,500 tons. A standing army of 1 million troops (some estimate as many as 1.9 million ) was created. The Chinese armies conquered Vietnam for around 20 years, while the Chinese fleet sailed the China seas and the Indian Ocean, cruising as far as the east coast of Africa. The Chinese gained influence in eastern Moghulistan. Several maritime Asian nations sent envoys with tribute for the Chinese emperor. Domestically, the Grand Canal was expanded and proved to be a stimulus to domestic trade. Over 100,000 tons of iron per year were produced. Many books were printed using movable type. The imperial palace in Beijing's Forbidden City reached its current splendor. It was also during these centuries that the potential of south China came to be fully exploited. New crops were widely cultivated and industries such as those producing porcelain and textiles flourished.

In 1449 Esen Tayisi led an Oirat Mongol invasion of northern China which culminated in the capture of the Zhengtong Emperor at Tumu. In 1542 the Mongol leader Altan Khan began to harass China along the northern border. In 1550 he even reached the suburbs of Beijing. The empire also had to deal with Japanese pirates attacking the southeastern coastline;[24] General Qi Jiguang was instrumental in defeating these pirates. The deadliest earthquake of all times, the Shaanxi earthquake of 1556 that killed approximately 830,000 people, occurred during the Jiajing Emperor's reign.

During the Ming dynasty the last construction on the Great Wall was undertaken to protect China from foreign invasions. While the Great Wall had been built in earlier times, most of what is seen today was either built or repaired by the Ming. The brick and granite work was enlarged, the watch towers were redesigned, and cannons were placed along its length.

Qing Dynasty (AD 1644–1911)

Capitals: Shenyang and Beijing

The Qing Dynasty (1644–1911) was the last imperial dynasty in China. Founded by the Manchus, it was the second non-Han Chinese dynasty. The Manchus were formerly known as Jurchen, residing in the northeastern part of the Ming territory outside the Great Wall. They emerged as the major threat to the late Ming Dynasty after Nurhaci united all Jurchen tribes and established an independent state. However, the Ming Dynasty would be overthrown by Li Zicheng's peasants rebellion, with Beijing captured in 1644 and the last Ming Emperor Chongzhen committing suicide. The Manchu allied with the Ming Dynasty general Wu Sangui to seize Beijing, which was made the capital of the Qing dynasty, and then proceeded to subdue the remaining Ming's resistance in the south. The decades of Manchu conquest caused enormous loss of lives and the economic scale of China shrank drastically. In total, the Manchu conquest of China (1618–1683) cost as many as 25 million lives.[25] Nevertheless, the Manchus adopted the Confucian norms of traditional Chinese government in their rule and were considered a Chinese dynasty.

The Manchus enforced a 'queue order,' forcing the Han Chinese to adopt the Manchu queue hairstyle and Manchu-style clothing. The traditional Han clothing, or Hanfu, was also replaced by Manchu-style clothing Qipao (bannermen dress and Tangzhuang). The Kangxi Emperor ordered the creation of Kangxi Dictionary, the most complete dictionary of Chinese characters ever put together at the time. The Qing dynasty set up the "Eight Banners" system that provided the basic framework for the Qing military organization. The bannermen were prohibited from participating in trade and manual labour unless they petitioned to be removed from banner status. They were considered a form of nobility and were given preferential treatment in terms of annual pensions, land and allotments of cloth.

Over the next half-century, all areas previously under the Ming Dynasty were consolidated under the Qing. Xinjiang, Tibet, and Mongolia were also formally incorporated into Chinese territory. Between 1673 and 1681, the Emperor Kangxi suppressed an uprising of three generals in Southern China who had been denied hereditary rule to large fiefdoms granted by the previous emperor; he also put down a Ming restorationist invasion from Taiwan, called the Revolt of the Three Feudatories. In 1683, the Qing staged an amphibious assault on southern Taiwan, bringing down the rebel Grand Duchy of Tungning, which was founded by the Ming loyalist Koxinga in 1662 after the fall of the Southern Ming, and had served as a base for continued Ming resistance in Southern China.

By the end of Qianlong Emperor's long reign, the Qing Empire was at its zenith. China ruled more than one-third of the world's population, and had the largest economy in the world. By area of extent, it was one of the largest empires ever in history.

In the 19th century, the empire was internally stagnated and externally threatened by imperialism. The defeat by the British Empire in the First Opium War (1840) led to the Treaty of Nanking (1842), under which Hong Kong was ceded and opium import was legitimized. Subsequent military defeats and unequal treaties with other imperial powers would continue even after the fall of the Qing Dynasty.

Internally, the Taiping Rebellion (1851–1864), a quasi-Christian religious movement led by the "Heavenly King" Hong Xiuquan, raided roughly a third of Chinese territory for over a decade until they were finally crushed in the Third Battle of Nanking in 1864. Arguably one of the largest wars in the 19th century in terms of troop involvement, there was massive loss of life, with a death toll of about 20 million.[26] A string of rebellions followed, which included the Punti–Hakka Clan Wars, Nien Rebellion, Muslim Rebellion, and Panthay Rebellion.[27] Although all rebellions were eventually put down at enormous cost and with many casualties, the central imperial authority was seriously weakened. The Banner system the Manchus had relied upon so long proved a total failure, as the Banner forces were unable to suppress the rebels. The government called upon local officials in the provinces who raised “New Armies,” which did prove a success in crushing the rebellion. China never rebuilt a strong central army, but the local officials often became warlords, who used military power to effectively rule independently in their provinces.[28]

In response to calamities within the empire and threats from imperialism, the Self-Strengthening Movement was an institutional reform in the second half of the 1800s. The aim was to modernize the empire, with prime emphasis on strengthening the military. However, the reform was undermined by corrupt officials, cynicism, and quarrels within the imperial family. As a result, the "Beiyang Fleet" were soundly defeated in the First Sino-Japanese War (1894–1895). Guangxu Emperor and the reformists then launched a more comprehensive reform effort, the Hundred Days' Reform (1898), but it was shortly overturned by the conservatives under Empress Dowager Cixi in a military coup.

At the turn of the 20th century, a conservative anti-foreign movement, the Boxer Rebellion, violently revolted against foreign influence in Northern China. The group proceeded to attack Chinese Christians and missionaries. The Empress Dowager, probably seeking to ensure her continual grip on power, sided with the Boxers as they advanced on Beijing. In response, a relief expedition of the Eight-Nation Alliance invaded China to rescue the besieged foreign missions. Consisting of British, Japanese, Russian, Italian, German, French, US, and Austrian troops, the alliance defeated the Boxers and demanded further concessions from the Qing government.

The early 1900s saw increasing civil disorder, despite reform talk by Cixi and the Qing government. Slavery in China was abolished in 1910.[29] The Xinhai Revolution in 1911 overthrew the Qing's imperial rule.

Modern China

Historians agree that the fall of the Qing dynasty demarcated the modern era in Chinese history. Scholars, however, are studying the reasons for that fall in the previous 130 years. Keith Schoppa, the editor of The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History argues, "A date around 1780 as the beginning of modern China is thus closer to what we know today as historical 'reality."' It also allows us to have a better baseline to understand the precipitous decline of the Chinese polity in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries."[30]

Republic of China (1912–1949)

Capitals: Nanjing, Beijing, Chongqing, and several short-lived wartime capitals; Taipei after 1949

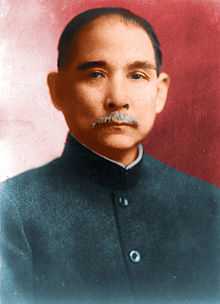

Frustrated by the Qing court's resistance to reform and by China's weakness, young officials, military officers, and students began to advocate the overthrow of the Qing Dynasty and the creation of a republic. They were inspired by the revolutionary ideas of Sun Yat-sen. A revolutionary military uprising, the Wuchang Uprising, began on 10 October 1911, in Wuhan. The provisional government of the Republic of China was formed in Nanjing on 12 March 1912.

Sun Yat-sen was declared President, but Sun was forced to turn power over to Yuan Shikai, who commanded the New Army and was Prime Minister under the Qing government, as part of the agreement to let the last Qing monarch abdicate (a decision Sun would later regret). Over the next few years, Yuan proceeded to abolish the national and provincial assemblies, and declared himself emperor in late 1915. Yuan's imperial ambitions were fiercely opposed by his subordinates; faced with the prospect of rebellion, he abdicated in March 1916, and died in June of that year.

Yuan's death in 1916 left a power vacuum in China; the republican government was all but shattered. This ushered in the Warlord Era, during which much of the country was ruled by shifting coalitions of competing provincial military leaders.

In 1919, the May Fourth Movement began as a response to the terms imposed on China by the Treaty of Versailles ending World War I, but quickly became a nationwide protest movement about the domestic situation in China. The protests were a moral success as the cabinet fell and China refused to sign the Treaty of Versailles, which had awarded German holdings to Japan. The New Culture Movement stimulated by the May Fourth Movement waxed strong throughout the 1920s and 1930s. According to Ebrey:

- "Nationalism, patriotism, progress, science, democracy, and freedom were the goals; imperialism, feudalism, warlordism, autocracy, patriarchy, and blind adherence to tradition where the enemies. Intellectuals struggled with how to be strong and modern and yet Chinese, how to preserve China as a political entity in the world of competing nations."[31]

The discrediting of liberal Western philosophy amongst leftist Chinese intellectuals led to more radical lines of thought inspired by the Russian Revolution, and supported by agents of the Comintern sent to China by Moscow. This created the seeds for the irreconcilable conflict between the left and right in China that would dominate Chinese history for the rest of the century.

In the 1920s, Sun Yat-sen established a revolutionary base in south China, and set out to unite the fragmented nation. With assistance from the Soviet Union (themselves fresh from a socialist uprising), he entered into an alliance with the fledgling Communist Party of China. After Sun's death from cancer in 1925, one of his protégés, Chiang Kai-shek, seized control of the Kuomintang (Nationalist Party or KMT) and succeeded in bringing most of south and central China under its rule in a military campaign known as the Northern Expedition (1926–1927). Having defeated the warlords in south and central China by military force, Chiang was able to secure the nominal allegiance of the warlords in the North. In 1927, Chiang turned on the CPC and relentlessly chased the CPC armies and its leaders from their bases in southern and eastern China. In 1934, driven from their mountain bases such as the Chinese Soviet Republic, the CPC forces embarked on the Long March across China's most desolate terrain to the northwest, where they established a guerrilla base at Yan'an in Shaanxi Province. During the Long March, the communists reorganized under a new leader, Mao Zedong (Mao Tse-tung).

The bitter struggle between the KMT and the CPC continued, openly or clandestinely, through the 14-year long Japanese occupation of various parts of the country (1931–1945). The two Chinese parties nominally formed a united front to oppose the Japanese in 1937, during the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), which became a part of World War II. Japanese forces committed numerous war atrocities against the civilian population, including biological warfare (see Unit 731) and the Three Alls Policy (Sankō Sakusen), the three alls being: "Kill All, Burn All and Loot All".[32]

Following the defeat of Japan in 1945, the war between the Nationalist government forces and the CPC resumed, after failed attempts at reconciliation and a negotiated settlement. By 1949, the CPC had established control over most of the country (see Chinese Civil War). Westad says the Communists won the Civil War because they made fewer military mistakes than Chiang, and because in his search for a powerful centralized government, Chiang antagonized too many interest groups in China. Furthermore, his party was weakened in the war against Japanese. Meanwhile the Communists told different groups, such as peasants, exactly what they wanted to hear, and cloaked themselves in the cover of Chinese Nationalism.[33] When the Nationalist government forces was defeated by CPC forces in mainland China in 1949, the Nationalist government retreated to Taiwan with its forces, along with Chiang and most of the KMT leadership and a large number of their supporters; the Nationalist government had taken effective control of Taiwan at the end of WWII as part of the overall Japanese surrender, when Japanese troops in Taiwan surrendered to Republic of China troops.[34]

People's Republic of China (1949–present)

Major combat in the Chinese Civil War ended in 1949 with Kuomintang (KMT) pulling out of the mainland, with the government relocating to Taipei and maintaining control only over a few islands. The Communist Party of China was left in control of mainland China. On 1 October 1949, Mao Zedong proclaimed the People's Republic of China.[35] "Communist China" and "Red China" were two common names for the PRC.[36]

.jpg)

The PRC was shaped by a series of campaigns and five-year plans. The economic and social plan known as the Great Leap Forward resulted in an estimated 45 million deaths.[37] Mao's government carried out mass executions of landowners, instituted collectivisation and implemented the Laogai camp system. In 1966, Mao and his allies launched the Cultural Revolution, which would last until Mao's death a decade later. The Cultural Revolution, motivated by power struggles within the Party and a fear of the Soviet Union, led to a major upheaval in Chinese society.

In 1972, at the peak of the Sino-Soviet split, Mao and Zhou Enlai met Richard Nixon in Beijing to establish relations with the United States. In the same year, the PRC was admitted to the United Nations in place of the Republic of China for China's membership of the United Nations, and permanent membership of the Security Council.

A power struggle followed Mao's death in 1976. The Gang of Four were arrested and blamed for the excesses of the Cultural Revolution, marking the end of a turbulent political era in China. Deng Xiaoping outmaneuvered Mao's anointed successor chairman Hua Guofeng, and gradually emerged as the de facto leader over the next few years.

Deng Xiaoping was the Paramount Leader of China from 1978 to 1992, although he never became the head of the party or state, and his influence within the Party led the country to significant economic reforms. The Communist Party subsequently loosened governmental control over citizens' personal lives and the communes were disbanded with many peasants receiving multiple land leases, which greatly increased incentives and agricultural production. This turn of events marked China's transition from a planned economy to a mixed economy with an increasingly open market environment, a system termed by some[38] as "market socialism", and officially by the Communist Party of China as "Socialism with Chinese characteristics". The PRC adopted its current constitution on 4 December 1982.

In 1989, the death of former general secretary Hu Yaobang helped to spark the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989, during which students and others campaigned for several months, speaking out against corruption and in favour of greater political reform, including democratic rights and freedom of speech. However, they were eventually put down on 4 June when PLA troops and vehicles entered and forcibly cleared the square, resulting in numerous casualties. This event was widely reported and brought worldwide condemnation and sanctions against the government.[39][40] The "Tank Man" incident in particular became famous.

CPC general secretary and PRC President Jiang Zemin and PRC Premier Zhu Rongji, both former mayors of Shanghai, led post-Tiananmen PRC in the 1990s. Under Jiang and Zhu's ten years of administration, the PRC's economic performance pulled an estimated 150 million peasants out of poverty and sustained an average annual gross domestic product growth rate of 11.2%.[41][42] The country formally joined the World Trade Organization in 2001.

Although the PRC needs economic growth to spur its development, the government has begun to worry that rapid economic growth has negatively impacted the country's resources and environment. Another concern is that certain sectors of society are not sufficiently benefiting from the PRC's economic development; one example of this is the wide gap between urban and rural areas. As a result, under former CPC general secretary and President Hu Jintao and Premier Wen Jiabao, the PRC has initiated policies to address these issues of equitable distribution of resources, but the outcome remains to be seen.[43] More than 40 million farmers have been displaced from their land,[44] usually for economic development, contributing to 87,000 demonstrations and riots across China in 2005.[45] For much of the PRC's population, living standards have seen extremely large improvements and freedom continues to expand, but political controls remain tight and rural areas poor.[46]

See also

- Chinese armour

- Chinese exploration

- Chinese historiography

- Chinese sovereign

- Economic history of China

- Ethnic groups in Chinese history

- Foreign relations of Imperial China

- Four occupations

- History of Hong Kong

- History of Islam in China

- History of Macau

- History of science and technology in China

- History of the Great Wall of China

- List of Chinese monarchs

- List of Neolithic cultures of China

- List of rebellions in China

- List of recipients of tribute from China

- List of tributaries of Imperial China

- Military history of China (pre-1911)

- Naval history of China

- Religion in China

- Timeline of Chinese history

Notes

- ↑ "China country profile". BBC News. 18 October 2010. Retrieved 2010-11-07.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "Public Summary Request Of The People's Republic Of China To The Government Of The United States Of America Under Article 9 Of The 1970 Unesco Convention". Bureau of Educational and Cultural Affairs, U.S. State Department. Archived from the original on 15 December 2007. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 "The Ancient Dynasties". University of Maryland. Retrieved 2008-01-12.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Rixiang Zhu, Zhisheng An, Richard Pott, Kenneth A. Hoffman (June 2003). "Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans of in China" (PDF). Earth Science Reviews 61 (3–4): 191–361.

- ↑ "Earliest Presence of Humans in Northeast Asia". Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Neolithic Period in China". Timeline of Art History. Metropolitan Museum of Art. October 2004. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Rice and Early Agriculture in China". Legacy of Human Civilizations. Mesa Community College. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Chinese writing '8,000 years old'". BBC News. 18 May 2007. Retrieved 2010-05-04.

- ↑ "Carvings may rewrite history of Chinese characters". Xinhua online. 18 May 2007. Retrieved 2007-05-19.

- ↑ "Peiligang Site". Ministry of Culture of the People's Republic of China. 2003. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Pringle, Heather (1998). "The Slow Birth of Agriculture". Science 282: 1446.

- ↑ Wertz, Richard R. (2007). "Neolithic and Bronze Age Cultures". Exploring Chinese History. ibiblio. Retrieved 2008-02-10.

- ↑ Bronze Age China at National Gallery of Art

- ↑ Scripts found on Erlitou pottery (written in Simplified Chinese)

- ↑ Boltz, William (1999). "Language and Writing". In Loewe, Michael; Shaughnessy, Edward L. The Cambridge History of Ancient China. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 74–123. ISBN 978-0-521-47030-8.

- ↑ Yu, Yingshi (1986). Denis Twitchett; Michael Loewe, eds. Cambridge History of China: Volume I: the Ch'in and Han Empires, 221 B.C. – A.D. 220. University of Cambridge Press. pp. 455–458. ISBN 978-0-5212-4327-8.

- ↑ Xu, Pingfang (2005). The Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective. Yale University Press. p. 281. ISBN 978-0-300-09382-7.

- ↑ Gernet, Jacques (1996). A History of Chinese Civilization. Cambridge University Press. pp. 126–127. ISBN 978-0-521-49781-7.

- ↑ Ban Chao, Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ Gabriel Ferrand, ed. (1922). Voyage du marchand arabe Sulaymân en Inde et en Chine, rédigé en 851, suivi de remarques par Abû Zayd Hasan (vers 916). p. 76.

- ↑ "Kaifung Jews". University of Cumbria, Division of Religion and Philosophy.

- ↑ Ho, Ping-ti (1970). "An Estimate of the Total Population of Sung-Chin China". Études Song. 1 (1): 33–53.

- ↑ "Course: Plague". Archived from the original on 18 November 2007.

- ↑ "China > History > The Ming dynasty > Political history > The dynastic succession", Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2007

- ↑ John M. Roberts (1997). A Short History of the World. Oxford University Press. p.272. ISBN 0-19-511504-X.

- ↑ White, Matthew. "Statistics of Wars, Oppressions and Atrocities of the Nineteenth Century". Retrieved 2007-04-11.

- ↑ Harper, Damsan; Fallon, Steve; Gaskell, Katja; Grundvig, Julie; Heller, Carolyn; Huhti, Thomas; Maynew, Bradley; Pitts, Christopher (2005). Lonely Planet China (9 ed.). ISBN 1-74059-687-0.

- ↑ Philip Kuhn, Rebellion and its Enemies in Late Imperial China: Militarization and Social Structure, 1796-1864 (1970) ch 6

- ↑ "Commemoration of the Abolition of Slavery Project". Archived from the original on 14 November 2007.

- ↑ R. Keith Schoppa (2000). The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia University Press. p. 15.

- ↑ Patricia Buckley Ebrey, Cambridge Illustrated History of China (1996) p 271

- ↑ Fairbank, J. K.; Goldman, M. (2006). China: A New History (2nd ed.). Harvard University Press. p. 320. ISBN 9780674018280.

- ↑ Odd Arne Westad, Restless Empire: China and the World Since 1750 (2012) p 291

- ↑ Surrender Order of the Imperial General Headquarters of Japan, 2 September 1945, "(a) The senior Japanese commanders and all ground, sea, air, and auxiliary forces within China (excluding Manchuria), Formosa, and French Indochina north of 16 degrees north latitude shall surrender to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek."

- ↑ The Chinese people have stood up. UCLA Center for East Asian Studies. Retrieved 16 April 2006.

- ↑ Smith, Joseph; and Davis, Simon. [2005] (2005). The A to Z of the Cold War. Issue 28 of Historical dictionaries of war, revolution, and civil unrest. Volume 8 of A to Z guides. Scarecrow Press publisher. ISBN 0-8108-5384-1, ISBN 978-0-8108-5384-3.

- ↑ Akbar, Arifa (17 September 2010). "Mao's Great Leap Forward 'killed 45 million in four years'". London: The Independent. Retrieved 30 October 2010.

- ↑ Hart-Landsberg, Martin; Burkett, Paul (March 2010). "China and Socialism: Market Reforms and Class Struggle". Monthly Review Press. ISBN 1-58367-123-4. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ Youngs, R. The European Union and the Promotion of Democracy. Oxford University Press, 2002. ISBN 978-0-19-924979-4.

- ↑ Carroll, J. M. A Concise History of Hong Kong. Rowman & Littlefield, 2007. ISBN 978-0-7425-3422-3.

- ↑ "Nation bucks trend of global poverty". China Daily. 11 July 2003.

- ↑ "China's Average Economic Growth in 90s Ranked 1st in World". People's Daily. 1 March 2000.

- ↑ "China worried over pace of growth". BBC. Retrieved 16 April 2006.

- ↑ "China: Migrants, Students, Taiwan". Migration News 13 (1). January 2006.

- ↑ "In Face of Rural Unrest, China Rolls Out Reforms". The Washington Post. 28 January 2006.

- ↑ Thomas, Antony (11 April 2006). "Frontline: The Tank Man transcript". Frontline. PBS. Retrieved 12 July 2008.

Bibliography

Surveys

- Blunden, Caroline, and Mark Elvin. Cultural Atlas of China (2nd ed 1998) excerpt and text search

- Catchpole, Brian. Map History of Modern China (1977)

- Eberharad, Wolfram. A History of China (2005), 380 pages' full text online free

- Ebrey, Patricia Buckley, and Kwang-ching Liu. The Cambridge Illustrated History of China (1999) 352 pages

- Fairbank, John King and Goldman, Merle. China: A New History. 2nd ed. Harvard U. Press, (2006). 640 pp.

- Gernet, Jacques, J. R. Foster, and Charles Hartman. A History of Chinese Civilization (1996), called the best one-volume survey;

- Hsu, Cho-yun. China: A New Cultural History (Columbia University Press; 2012) 612 pages; stress on China's encounters with successive waves of globalization.

- Hsü, Immanuel Chung-yueh. The Rise of Modern China, 6th ed. (Oxford University Press, 1999), highly detailed coverage of 1644–1999, in 1136pp.

- Huang, Ray. China, a Macro History (1997) 335pp, an idiosyncratic approach, not for beginners; online edition from Questia

- Keay, John. China: A History (2009), 642pp

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott. The Development of China (1917) 273 pages; full text online outdated survey

- Franz, Michael. China through the Ages: History of a Civilization. (1986). 278pp; online edition from Questia

- Mote, Frederick W. Imperial China, 900–1800 Harvard University Press, 1999, 1,136 pages, the authoritative treatment of the Song, Yuan, Ming, and Qing dynasties;

- Perkins, Dorothy. Encyclopedia of China: The Essential Reference to China, Its History and Culture. Facts on File, 1999. 662 pp.

- Roberts, J. A. G. A Concise History of China. Harvard U. Press, 1999. 341 pp.

- Schoppa, R. Keith. The Columbia Guide to Modern Chinese History. Columbia U. Press, 2000. 356 pp. online edition from Questia

- Spence, Jonathan D. The Search for Modern China (1999), 876pp; survey from 1644 to 1990s complete edition online at Questia

- Ven, Hans van de, ed. Warfare in Chinese History. E. J. Brill, 2000. 456 pp. online edition

- Wang, Ke-wen, ed. Modern China: An Encyclopedia of History, Culture, and Nationalism. Garland, 1998. 442 pp.

- Wright, David Curtis. History of China (2001) 257pp; online edition

- Wills, Jr., John E. Mountain of Fame: Portraits in Chinese History (1994)

Prehistory

- Chang, Kwang-chih. The Archaeology of Ancient China, Yale University Press, 1986.

- Discovery of residue from fermented beverage consumed up to 9,000 years ago in Jiahu, Henan Province, China. By Dr. Patrick E McGovern, University of Pennsylvania archaeochemist and colleagues from China, Great Britain and Germany.

- Zhu, Rixiang; Zhisheng An, Richard Potts, Kenneth A. Hoffman. "Magnetostratigraphic dating of early humans in China" (PDF). doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(02)00132-0. Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- The Discovery of Early Pottery in China by Zhang Chi, Department of Archaeology, Peking University, China.

Shang Dynasty

- Durant, Stephen W. The Cloudy Mirror: Tension and Conflict in the Writings of Sima Qian (1995),

Han Dynasty

- de Crespigny, Rafe. 1972. The Ch’iang Barbarians and the Empire of Han: A Study in Frontier Policy. Papers on Far Eastern History 16, Australian National University. Canberra.

- de Crespigny, Rafe. 1984. Northern Frontier. The Policies and Strategies of the Later Han Empire. Rafe de Crespigny. 1984. Faculty of Asian Studies, Australian National University. Canberra.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1990). Chapter One from Generals of the South: the Foundation and early history of the Three Kingdoms state of Wu. "South China under the Later Han Dynasty". Asian Studies Monographs, New Series No. 16 (Faculty of Asian Studies, The Australian National University, Canberra). Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1996). "Later Han Military Administration: An Outline of the Military Administration of the Later Han Empire". Asian Studies Monographs, New Series No. 21 (Based on the Introduction to Emperor Huan and Emperor Ling being the Chronicle of Later Han for the years 189 to 220 CE as recorded in Chapters 59 to 69 of the Zizhi tongjian of Sima Guang ed.) (Faculty of Asian Studies, The Australian National University). Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- Dubs, Homer H. 1938–55. The History of the Former Han Dynasty by Pan Ku. (3 vol)

- Hill, John E. Through the Jade Gate to Rome: A Study of the Silk Routes during the Later Han Dynasty, 1st to 2nd centuries CE. (2009) ISBN 978-1-4392-2134-1.

- Hulsewé, A. F. P. and Loewe, M. A. N., eds. China in Central Asia: The Early Stage 125 BCE – CE 23: an annotated translation of chapters 61 and 96 of the History of the Former Han Dynasty. (1979)

- Twitchett, Denis and Loewe, Michael, eds. 1986. The Cambridge History of China. Volume I. The Ch’in and Han Empires, 221 BCE – CE 220. Cambridge University Press.

- Yap, Joseph P. ``Wars With the Xiongnu – A Translation From Zizhi tongjian`` (Zhan-guo, Qin, Han and Xin 403 BCE – 23 CE.) AuthorHouse (2009) ISBN 1-4900-0604-4

Jin, the Sixteen Kingdoms, and the Northern and Southern Dynasties

- de Crespigny, Rafe (1991). "The Three Kingdoms and Western Jin: A History of China in the Third Century AD". East Asian History (Faculty of Asian Studies, Australian National University, Canberra) (1 June 1991, pp. 1–36, & no. 2 December 1991, pp. 143–164). Retrieved 2011-01-23.

- Miller, Andrew. Accounts of Western Nations in the History of the Northern Chou Dynasty. (1959)

Sui Dynasty

- Wright, Arthur F. 1978. The Sui Dynasty: The Unification of China. CE 581–617. Alfred A. Knopf, New York. ISBN 0-394-49187-4, ISBN 0-394-32332-7 (pbk).

Tang Dynasty

- Benn, Charles. 2002. China's Golden Age: Everyday Life in the Tang Dynasty. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-517665-0.

- Schafer, Edward H. 1963. The Golden Peaches of Samarkand: A study of T’ang Exotics. University of California Press. Berkeley and Los Angeles. 1st paperback edition. 1985. ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- Schafer, Edward H. 1967. The Vermilion Bird: T’ang Images of the South. University of California Press, Berkeley and Los Angeles. Reprint 1985. ISBN 0-520-05462-8.

- Shaffer, Lynda Norene. 1996. Maritime Southeast Asia to 1500. Armonk, New York, M.E. Sharpe, Inc. ISBN 1-56324-144-7.

- Wang, Zhenping. 1991. "T’ang Maritime Trade Administration." Wang Zhenping. Asia Major, Third Series, Vol. IV, 1991, pp. 7–38.

Song Dynasty

- Ebrey, Patricia. The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period (1990)

- Hymes, Robert, and Conrad Schirokauer, eds. Ordering the World: Approaches to State and Society in Sung Dynasty China, U of California Press, 1993; complete text online free

- Shiba, Yoshinobu. 1970. Commerce and Society in Sung China. Originally published in Japanese as So-dai sho-gyo—shi kenkyu-. Tokyo, Kazama shobo-, 1968. Yoshinobu Shiba. Translation by Mark Elvin, Centre for Chinese Studies, University of Michigan.

Ming Dynasty

- Brook, Timothy. The Confusions of Pleasure: Commerce and Culture in Ming China. (1998).

- Brook, Timothy. The Troubled Empire: China in the Yuan and Ming Dynasties (2010) 329 pages. Focus on the impact of a Little Ice Age on the empire, as the empire, beginning with a sharp drop in temperatures in the 13th century during which time the Mongol leader Kubla Khan moved south into China.

- Dardess, John W. A Ming Society: T'ai-ho County, Kiangsi, Fourteenth to Seventeenth Centuries. (1983); uses advanced "new social history" complete text online free

- Farmer, Edward. Zhu Yuanzhang and Early Ming Legislation: The Reordering of Chinese Society Following the Era of Mongol Rule. E.J. Brill, 1995.

- Goodrich, L. Carrington, and Chaoying Fang. Dictionary of Ming Biography. (1976).

- Huang, Ray. 1587, A Year of No Significance: The Ming Dynasty in Decline. (1981).

- Mote, Frederick W. and Twitchett, Denis, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 7: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1. (1988). 976 pp.

- Schneewind, Sarah. A Tale of Two Melons: Emperor and Subject in Ming China. (2006).

- Tsai, Shih-shan Henry. Perpetual Happiness: The Ming Emperor Yongle. (2001).

- Mote, Frederick W., and Denis Twitchett, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 7, part 1: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644 (1988). 1008 pp. excerpt and text search

- Twitchett, Denis and Frederick W. Mote, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 1.

- Twitchett, Denis and Frederick W. Mote, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 8: The Ming Dynasty, 1368–1644, Part 2. (1998). 1203 pp.

Qing Dynasty

- Fairbank, John K. and Liu, Kwang-Ching, ed. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 2: Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911, Part 2. Cambridge U. Press, 1980. 754 pp.

- Mann, Susan. Precious Records: Women in China's Long Eighteenth Century (1997)

- Naquin, Sysan, and Evelyn S. Rawski. Chinese Society in the Eighteenth Century (1989) excerpt and text search

- Peterson, Willard J., ed. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 9, Part 1: The Ch'ing Dynasty to 1800. Cambridge U. Press, 2002. 753 pp.

- Rawski, Evelyn S. The Last Emperors: A Social History of Qing Imperial Institutions (2001) complete text online free

- Struve, Lynn A., ed. The Qing Formation in World-Historical Time. (2004). 412 pp.

- Struve, Lynn A., ed. Voices from the Ming-Qing Cataclysm: China in Tigers' Jaws (1998)

- Yizhuang, Ding. "Reflections on the 'New Qing History' School in the United States," Chinese Studies in History, Winter 2009/2010, Vol. 43 Issue 2, pp 92–96, It drops the theme of "sinification" in evaluating the dynasty and the non-Han Chinese regimes in general. It seeks to analyze the success and failure of Manchu rule in China from the Manchu perspective and focus on how Manchu rulers sought to maintain the Manchu ethnic identity throughout Qing history.

Republican era

- Bergere, Marie-Claire. Sun Yat-Sen (1998), 480pp, the standard biography

- Boorman, Howard L., ed. Biographical Dictionary of Republican China. (Vol. I-IV and Index. 1967–1979). 600 short scholarly biographies excerpt and text search

- Boorman, Howard L. "Sun Yat-sen" in Boorman, ed. Biographical Dictionary of Republican China (1970) 3: 170–89, '%C3%9C-Y%C3%9CN&source=web&ots=2vo5nB_pW4&sig=z9_ba59M35GI7n85WvjZR5zS3HU&hl=en&sa=X&oi=book_result&resnum=1&ct=result#PPA170,M1 complete text online

- Dreyer, Edward L. China at War, 1901–1949. (1995). 422 pp.

- Eastman Lloyd. Seeds of Destruction: Nationalist China in War and Revolution, 1937– 1945. (1984)

- Eastman Lloyd et al. The Nationalist Era in China, 1927–1949 (1991)

- Fairbank, John K., ed. The Cambridge History of China, Vol. 12, Republican China 1912–1949. Part 1. (1983). 1001 pp.

- Fairbank, John K. and Feuerwerker, Albert, eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 13: Republican China, 1912–1949, Part 2. (1986). 1092 pp.

- Fogel, Joshua A. The Nanjing Massacre in History and Historiography (2000)

- Gordon, David M. "The China-Japan War, 1931–1945," The Journal of Military History v70#1 (2006) 137–182; major historiographical overview of all important books and interpretations; online

- Hsiung, James C. and Steven I. Levine, eds. China's Bitter Victory: The War with Japan, 1937–1945 (1992), essays by scholars; online from Questia;

- Hsi-sheng, Ch'i. Nationalist China at War: Military Defeats and Political Collapse, 1937–1945 (1982)

- Hung, Chang-tai. War and Popular Culture: Resistance in Modern China, 1937–1945 (1994) complete text online free

- Lara, Diana. The Chinese People at War: Human Suffering and Social Transformation, 1937–1945 (2010)

- Rubinstein, Murray A., ed. Taiwan: A New History (2006), 560pp

- Shiroyama, Tomoko. China during the Great Depression: Market, State, and the World Economy, 1929–1937 (2008)

- Shuyun, Sun. The Long March: The True History of Communist China's Founding Myth (2007)

- Taylor, Jay. The Generalissimo: Chiang Kai-shek and the Struggle for Modern China. (2009) ISBN 978-0-674-03338-2

- Westad, Odd Arne. Decisive Encounters: The Chinese Civil War, 1946–1950. (2003). 413 pp. the standard history

Communist era, 1949– present

- Barnouin, Barbara, and Yu Changgen. Zhou Enlai: A Political Life (2005)

- Baum, Richard D. "'Red and Expert': The Politico-Ideological Foundations of China's Great Leap Forward," Asian Survey, Vol. 4, No. 9 (Sep. 1964), pp. 1048–1057 in JSTOR

- Becker, Jasper. Hungry Ghosts: China's Secret Famine (1996), on the "Great Leap Forward" of 1950s

- Chang, Jung and Jon Halliday. Mao: The Unknown Story, (2005), 814 pages, ISBN 0-679-42271-4

- Davin, Delia (2013). Mao: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford UP.

- Dittmer, Lowell. China's Continuous Revolution: The Post-Liberation Epoch, 1949–1981 (1989) online free

- Dietrich, Craig. People's China: A Brief History, 3d ed. (1997), 398pp

- Kirby, William C., ed. Realms of Freedom in Modern China. (2004). 416 pp.

- Kirby, William C.; Ross, Robert S.; and Gong, Li, eds. Normalization of U.S.-China Relations: An International History. (2005). 376 pp.

- Li, Xiaobing. A History of the Modern Chinese Army (2007)

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Fairbank, John K., eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966–1982. Cambridge U. Press, 1992. 1108 pp.

- Meisner, Maurice. Mao's China and After: A History of the People’s Republic, 3rd ed. (Free Press, 1999), dense book with theoretical and political science approach.

- Spence, Jonatham. Mao Zedong (1999)

- Shuyun, Sun. The Long March: The True History of Communist China's Founding Myth (2007)

- Wang, Jing. High Culture Fever: Politics, Aesthetics, and Ideology in Deng's China (1996) complete text online free

- Wenqian, Gao. Zhou Enlai: The Last Perfect Revolutionary (2007)

Cultural Revolution, 1966–76

- Clark, Paul. The Chinese Cultural Revolution: A History (2008), a favorable look at artistic production excerpt and text search

- Esherick, Joseph W.; Pickowicz, Paul G.; and Walder, Andrew G., eds. The Chinese Cultural Revolution as History. (2006). 382 pp.

- Jian, Guo; Song, Yongyi; and Zhou, Yuan. Historical Dictionary of the Chinese Cultural Revolution. (2006). 433 pp.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Fairbank, John K., eds. The Cambridge History of China. Vol. 15: The People's Republic, Part 2: Revolutions within the Chinese Revolution, 1966–1982. Cambridge U. Press, 1992. 1108 pp.

- MacFarquhar, Roderick and Michael Schoenhals. Mao's Last Revolution. (2006).

- MacFarquhar, Roderick. The Origins of the Cultural Revolution. Vol. 3: The Coming of the Cataclysm, 1961–1966. (1998). 733 pp.

- Yan, Jiaqi and Gao, Gao. Turbulent Decade: A History of the Cultural Revolution. (1996). 736 pp.

Economy and environment

- Chow, Gregory C. China's Economic Transformation (2nd ed. 2007)

- Elvin, Mark. Retreat of the Elephants: An Environmental History of China. (2004). 564 pp.

- Elvin, Mark and Liu, Ts'ui-jung, eds. Sediments of Time: Environment and Society in Chinese History. (1998). 820 pp.

- Ji, Zhaojin. A History of Modern Shanghai Banking: The Rise and Decline of China's Finance Capitalism. (2003. 325) pp.

- Naughton, Barry. The Chinese Economy: Transitions and Growth (2007)

- Rawski, Thomas G. and Lillian M. Li, eds. Chinese History in Economic Perspective, University of California Press, 1992 complete text online free

- Sheehan, Jackie. Chinese Workers: A New History. Routledge, 1998. 269 pp.

- Stuart-Fox, Martin. A Short History of China and Southeast Asia: Tribute, Trade and Influence. (2003). 278 pp.

Women and gender

- Ebrey, Patricia. The Inner Quarters: Marriage and the Lives of Chinese Women in the Sung Period (1990)

- Hershatter, Gail, and Wang Zheng. "Chinese History: A Useful Category of Gender Analysis," American Historical Review, Dec 2008, Vol. 113 Issue 5, pp 1404–1421

- Hershatter, Gail. Women in China's Long Twentieth Century (2007), full text online

- Hershatter, Gail, Emily Honig, Susan Mann, and Lisa Rofel, eds. Guide to Women's Studies in China (1998)

- Ko, Dorothy. Teachers of Inner Chambers: Women and Culture in China, 1573–1722 (1994)

- Mann, Susan. Precious Records: Women in China's Long Eighteenth Century (1997)

- Wang, Shuo. "The 'New Social History' in China: The Development of Women's History," History Teacher, May 2006, Vol. 39 Issue 3, pp 315–323

Further reading

- Classical Historiography For Chinese History

- Abramson, Marc S. (2008). Ethnic Identity in Tang China. University of Pennsylvania Press, Philadelphia. ISBN 978-0-8122-4052-8.

- Ankerl, G. C. Coexisting Contemporary Civilizations: Arabo-Muslim, Bharati, Chinese, and Western. INU PRESS Geneva, 2000. ISBN 2-88155-004-5.

- Li, Xiaobing. China at War: An Encyclopedia (2012) in ebrary

- Wilkinson, Endymion Porter, Chinese history: a manual, (revised and enlarged. Harvard University, Asia Center (for the Harvard-Yenching Institute), 2000, 1181 p., ISBN 0-674-00247-4; ISBN 0-674-00249-0; for specialists.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of China. |

- Chinese Database by Academia Sinica (Chinese)

- Modernizing China from the Dean Peter Krogh Foreign Affairs Digital Archives

- Manuscript and Graphics Database by Academia Sinica (Chinese)

- A universal guide for China studies

- Oriental Style The Genuine Soul of Ancient Chinese People

- Chinese Text Project Texts and translations of historical Chinese works.

- Chinese Siege Warfare – Mechanical Artillery and Siege Weapons of Antiquity – An Illustrated History bought to you by History Forum

- Yin Yu Tang: A Chinese Home Explore the historical contents of domestic architecture during the Qing dynasty and its pertinence to Chinese heritage and historical culture.

- Early Medieval China is a journal devoted to academic scholarship relating to the period roughly between the end of the Han and beginning of the Tang eras.

- Cultural Revolution Propaganda Poster

- China Rediscovers its Own History 100-minute lecture on Chinese history given by renowned scholar/author Yu Ying-shih, Emeritus Professor of East Asian Studies and History at Princeton University.

- Resources for Middle School students Readable resources for students in grades 5–9 – more than 250 links.

- Wolfram Eberhard, A history of China (online), 7 February 2006 [EBook #17695], ISO-8859-1

- China from the Inside – 2006 PBS documentary. KQED Public Television and Granada Television for PBS, Granada International and the BBC

- Ancient Asian World History, culture and archaeology of the ancient Asian continent. Many articles and pictures

- History of China: Table of Contents – Chaos Group at University of Maryland

- History Forum – Discuss Chinese history at History Forum's Asian History section

- Li (2010). "Evidence that a West-East admixed population lived in the Tarim Basin as early as the early Bronze Age" (PDF). BMC Biology (8:15).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||