Dzungaria

| Dzungaria | |||||||||||

Dzungaria | |||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 准噶尔 | ||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 準噶爾 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Beijiang | |||||||||||

| Chinese | 北疆 | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Mongolian name | |||||||||||

| Mongolian | Зүүнгарын нутаг | ||||||||||

| Uyghur name | |||||||||||

| Uyghur |

جوڭغار | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Russian name | |||||||||||

| Russian | Джунгария | ||||||||||

| Romanization | Dzhungariya | ||||||||||

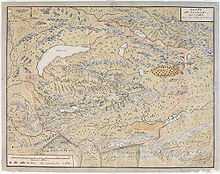

Dzungaria is a geographical region in northwest China corresponding to the northern half of Xinjiang, also known as Beijiang (Chinese: 北疆; pinyin: Běijiāng; literally "Northern Xinjiang"). Bounded by the Tian Shan mountain range to the south and the Altai Mountains to the north, it covers approximately 777,000 km2 (300,000 sq mi), extending into western Mongolia and eastern Kazakhstan. Formerly the term could cover a wider area, if considered conterminous with the Dzungar Khanate, a separatist state led by the native Oirat Mongols in the 18th century which was based in the area.

Although geographically, historically, and ethnically distinct from the Turkic-speaking Tarim Basin area, the Qing Dynasty and subsequent Chinese governments integrated both areas into one province, Xinjiang. As the center of Xinjiang's heavy industry, generator of most of Xinjiang's GDP, as well as containing its political capital Ürümqi ("beautiful pasture" in Mongolian), northern Xinjiang continues to attract intraprovincial and interprovincial migration to its cities. In comparison to southern Xinjiang (Nanjiang, or the Tarim Basin), Dzungaria is relatively well-integrated with the rest of China by rail and trade links.[1]

Etymology

The name Dzungaria is a corruption of the Mongolian term "Züün Gar" or "Jüün Gar" depending on the dialect of Mongolian used. "Züün"/"Jüün" means "left" and "Gar" means "hand". The name originates from the notion that the Western Mongols are on the left hand side when the Mongol Empire began its division into East and West Mongols. After this fragmentation, the western Mongolian nation was called "Zuun Gar". Today, the cradle of this former nation retains its name: Zungaria.

Dzungarian Basin

The core of Dzungaria is the triangular Dzungarian Basin (also Junggar Basin) with its central Gurbantunggut Desert. It is bounded by the Tien Shan to the south, the Altai Mountains to the northeast and the Tarbagatai Mountains to the northwest.[2] The three corners are relatively open. The northern corner is the valley of the upper Irtysh River. The western corner is the Dzungarian Gate, a historically important gateway between Dzungaria and the Kazakh Steppe; presently, a highway and a railway (opened in 1990) run through it, connecting China with Kazakhstan. The eastern corner of the basin leads to Gansu and the rest of China. In the south an easy pass leads from Ürümqi to the Turfan Depression. In the southwest the tall Borohoro Mountains branch of the Tian Shan separates the basin from the upper Ili River.

The basin is similar to the larger Tarim Basin on the southern side of the Tian Shan Range. Only a gap in the mountains to the north allows moist air masses to provide the basin lands with enough moisture to remain semi-desert rather than becoming a true desert like most of the Tarim Basin, and allows a thin layer of vegetation to grow. This is enough to sustain populations of wild camels, jerboas, and other wild species.[3]

The Dzungarian Basin is a structural basin with thick sequences of Paleozoic-Pleistocene rocks with large estimated oil reserves.[4] The Gurbantunggut Desert, China’s second largest, is in the center of the basin.[5]

The Dzungarian basin does not have a single catchment center. The northernmost section of Dzungaria is part of the basin of the Irtysh River, which ultimately drains into the Arctic Ocean. The rest of the region is split into a number of endorheic basins. In particular, south of the Irtysh, the Ulungur River ends up in the (presently) endorheic Lake Ulungur. The Southwestern part of the Dzungarian basin drains into the Aibi Lake. In the west-central part of the region, streams flow into (or toward) a group of endorheic lakes that include Lake Manas and Lake Ailik. During the region's geological past, a much larger lake (the "Old Manas Lake") was located in the area of today's Manas Lake; it was fed not only by the streams that presently flow toward it, but also by the Irtysh and Ulungur, which too were flowing toward the Old Manas Lake at the time.[6]

The cold climate of nearby Siberia influences the climate of the Dzungarian Basin, making the temperature colder—as low as −4 °F (−20 °C)—and providing more precipitation, ranging from 3 to 10 inches (76 to 254 mm), compared to the warmer, drier basins to the south. Runoff from the surrounding mountains into the basin supplies several lakes. The ecologically rich habitats traditionally included meadows, marshlands, and rivers. However most of the land is now used for agriculture.[3]

It is a largely steppe and semi-desert basin surrounded by high mountains: the Tian Shan (ancient Mount Imeon) in the south and the Altai in the north. Geologically it is an extension of the Paleozoic Kazakhstan Block and was once part of an independent continent before the Altai mountains formed in the late Paleozoic. It does not contain the abundant minerals of Kazakhstan and may have been a pre-existing continental block before the Kazakhstan Block was formed.

Ürümqi, Yining and Karamai are the main cities; other smaller oasis towns dot the piedmont areas.

Paleontology

Dzungaria and its derivatives are used to name a number of pre-historic animals[7] hailing from the rocky outcrops located in an eponymous sedimentary basin of that region, the Junggar Basin.

- Dsungaripterus weii (pterosaur)

- Junggarsuchus sloani (crocodylomorph)

A recent notable find, in February 2006, is the oldest tyrannosaur fossil unearthed by a team of scientists from George Washington University who were conducting a study in the Dzungarian Basin. The species, named Guanlong, lived 160 million years ago, more than 90 million years before the famed Tyrannosaurus rex.[citation needed]

Ecology

Dzungaria is home to a semi-desert steppe ecoregion known as the Dzungarian Basin semi-desert. The vegetation consists mostly of low scrub of Anabasis brevifolia. Taller shrublands of saxaul bush (Haloxylon ammodendron) and Ephedra przewalskii can be found near the margins of the basin. Streams descending from the Tian Shan and Altai ranges support stands of poplar (Populus diversifolia) together with Nitraria roborovsky, N. sibirica, Achnatherum splendens, tamarisk (Tamarix sibirimosissima), and willow (Salix ledebouriana).

The northeastern portion of the Dzungarian Basin semi-desert lies within Great Gobi National Park, and is home to herds of Asian wild ass (Equus hemionus) and goitered gazelle (Gazella subgutturosa), and wild Bactrian camels (Camelus ferus).

The basin was one of the last habitats of Przewalski's Horse (Equus przewalskii), which is now extinct in the wild.

History

One of the earliest mentions of the Dzungaria region occurs when the Han Dynasty dispatched an explorer to investigate lands to the west, using the northernmost Silk Road trackway of about 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) in length, which connected the ancient Chinese capital of Xi'an to the west over the Wushao Ling Pass to Wuwei and emerged in Kashgar.[8]

Istämi of the Göktürks received the lands of Dzungaria as an inheritance after the death of his father in the latter half of the sixth century AD.[9]

Dzungaria is named after a Mongolian kingdom which existed in Central Asia during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. It derived its name from the Dzungars, who were so called because they formed the left wing (züün, left; gar, hand) of the Mongolian army, self-named Oirats. Dzungar power reached its height in the second half of the 17th century, when Kaldan (also known as Galdan Boshigtu Khan), repeatedly intervened in the affairs of the Kazakhs to the west, but it was completely destroyed by the Kazakhs about 1757–1759. It has played an important part in the history of Mongolia and the great migrations of Mongolian stems westward.

Since 1761, its territory fell mostly to the Qing dynasty (Xinjiang and north-western Mongolia) and partly to Russian Turkestan (earlier Kazakh state provinces of Semirechye- Jetysu and Irtysh river).

Its widest limit included Kashgar, Yarkand, Khotan, the whole region of the Tian Shan, and in short the greater proportion of that part of Central Asia which extends from 35° to 50° N and from 72° to 97° E.

As a political or geographical term Dzungaria has practically disappeared from the map; but the range of mountains stretching north-east along the southern frontier of the Jeti-su, as the district to the south-east of Lake Balkhash preserves the name of Dzungarian Alatau. It also gave name to Dzungarian Hamsters.

Dzungaria and the Silk Road

A traveler going west from China must go either north of the Tien Shan through Dzungaria or south of the Tien Shan through the Tarim Basin. Trade usually took the south side and migrations the north. This is most likely because the Tarim leads to the Ferghana Valley and Iran, while Dzungaria leads only to the open steppe. The difficulty with south side was the high mountains between the Tarim and Ferghana. There is also another reason. The Taklamakan is too dry to support much grass, and therefore nomads when they are not robbing caravans. Its inhabitants live mostly in oases formed where rivers run out of the mountains into the desert. These are inhabited by peasants who are unwarlike and merchants who have an interest in keeping trade running smoothly. Dzungaria has a fair amount of grass, few towns to base soldiers in and no significant mountain barriers to the west. Therefore trade went south and migrations north.[10]

People

The Dzungar (or Zunghar), Oirat Mongols who lived in an area that stretched from the west end of the Great Wall of China to present-day eastern Kazakhstan and from present-day northern Kyrgyzstan to southern Siberia (most of this area is called Xinjiang nowadays), were the last nomadic empire to threaten China, which they did from the early 17th century to the middle of the 18th century.[11] After a series of inconclusive military conflicts that started in the 1680s, the Dzungars were subjugated by the Manchu-led Qing dynasty (1644–1911) in the late 1750s. According to Qing scholar Wei Yuan, 40% of the 600,000 Zunghar people were killed by smallpox, 20% fled to Russia or sought refuge among the Kazakh tribes, and 30% were killed by the army.[12][13] Clarke has argued that the Qing campaign in 1757–58 "amounted to the complete destruction of not only the Zunghar state but of the Zunghars as a people."[14] Historian Peter Perdue has attributed the decimation of the Dzungars to a "deliberate use of massacre" and has described it as an "ethnic genocide".[13] Mark Levene, a historian whose recent research interests focus on genocide,[15] has stated that the extermination of the Dzungars was "arguably the eighteenth century genocide par excellence."[16] The Qing subsequently began to repopulate the area with Turki people from the south (the Turkic-speaking peoples now known as Uyghurs).

The population in the 21st century consists of Kazakhs, Kyrgyz, Mongols, Uyghurs and Han Chinese. Since 1953, northern Xinjiang has attracted skilled workers from all over China—who have mostly been Han Chinese—to work on water conservation and industrial projects, especially the Karamay oil fields. Intraprovincial migration has mostly been directed towards Dzungaria also, with immigrants from the poor Uyghur areas of southern Xinjiang flooding to the provincial capital of Ürümqi to find work.

Economy

Wheat, barley, oats, and sugar beets are grown, and cattle, sheep, and horses are raised. The fields are irrigated with melted snow from the permanently white-capped mountains.

Dzungaria has deposits of coal, iron, and gold, as well as large oil fields.

References

- ↑ Stahle, Laura N (August 2009). "Ethnic Resistance and State Environmental Policy: Uyghurs and Mongols". University of southern California.

- ↑ "Junggar Basin". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 World Wildlife Fund (2001). "Junggar Basin semi-desert". WildWorld Ecoregion Profile. National Geographic Society. Archived from the original on 2010-03-08. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ "Geochemistry of oils from the Junggar Basin, Northwest China". AAPG Bulletin, GeoScience World. 1997. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ "Junggar Basin semi-desert". Terrestrial Ecoregions. World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2008-02-13.

- ↑ Yao, Yonghui; Li, Huiguo (2010), "Tectonic geomorphological characteristics for evolution of the Manas Lake", JOURNAL OF ARID LAND 2 (3): 167−173

- ↑ Nature, Nature Publishing Group, Norman Lockyer, 1869

- ↑ Silk Road, North China, C.Michael Hogan, the Megalithic Portal, ed. A. Burnham

- ↑ The Empire of the Steppes: A History of Central Asia, By René Grousset

- ↑ Grosset, 'The Empire of the Steppes', p xxii,

- ↑ Chapters 3–7 of Perdue 2005 describe the rise and fall of the Dzungar empire and its relations with other Mongol tribes, the Qing dynasty, and the Russian empire.

- ↑ Wei Yuan, 聖武記 Military history of the Qing Dynasty, vol.4. "計數十萬戶中,先痘死者十之四,繼竄入俄羅斯哈薩克者十之二,卒殲於大兵者十之三。"

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Perdue 2005, p. 283-285.

- ↑ Clarke 2004, p. 37.

- ↑ Dr. Mark Levene, Southampton University, see "Areas where I can offer Postgraduate Supervision". Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- ↑ Levene 2008, p. 188

Sources

![]() This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Coordinates: 45°00′N 85°00′E / 45.000°N 85.000°E