Dynamometer

- For the dynamometer used in railroading, see dynamometer car.

- For the climbing technique, see dyno (climbing).

.jpg)

A dynamometer or "dyno" for short, is a device for measuring force, moment of force (torque), or power. For example, the power produced by an engine, motor or other rotating prime mover can be calculated by simultaneously measuring torque and rotational speed (RPM).

A dynamometer can also be used to determine the torque and power required to operate a driven machine such as a pump. In that case, a motoring or driving dynamometer is used. A dynamometer that is designed to be driven is called an absorption or passive dynamometer. A dynamometer that can either drive or absorb is called a universal or active dynamometer.

In addition to being used to determine the torque or power characteristics of a machine under test (MUT), dynamometers are employed in a number of other roles. In standard emissions testing cycles such as those defined by the United States Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), dynamometers are used to provide simulated road loading of either the engine (using an engine dynamometer) or full powertrain (using a chassis dynamometer). In fact, beyond simple power and torque measurements, dynamometers can be used as part of a testbed for a variety of engine development activities, such as the calibration of engine management controllers, detailed investigations into combustion behavior, and tribology.

In the medical terminology, hand-held dynamometers are used for routine screening of grip and hand strength, and the initial and ongoing evaluation of patients with hand trauma or dysfunction. They are also used to measure grip strength in patients where compromise of the cervical nerve roots or peripheral nerves is suspected.

In the rehabilitation, kinesiology, and ergonomics realms, force dynamometers are used for measuring the back, grip, arm, and/or leg strength of athletes, patients, and workers to evaluate physical status, performance, and task demands. Typically the force applied to a lever or through a cable is measured and then converted to a moment of force by multiplying by the perpendicular distance from the force to the axis of the level.[1]

Principles of operation of torque power (absorbing) dynamometers

An absorbing dynamometer acts as a load that is driven by the prime mover that is under test (e.g. Pelton wheel). The dynamometer must be able to operate at any speed and load to any level of torque that the test requires.

Absorbing dynamometers are not to be confused with "inertia" dynamometers, which calculate power solely by measuring power required to accelerate a known mass drive roller and provide no variable load to the prime mover.

An absorption dynamometer is usually equipped with some means of measuring the operating torque and speed.

The Power Absorption Unit of a dynamometer absorbs the power developed by the prime mover. This power absorbed by the dynamometer is then converted into heat, which generally dissipates into the ambient air or transfers to cooling water that dissipates into the air. Regenerative dynamometers, in which the prime mover drives a DC motor as a generator to create load, make excess DC power and potentially - using a DC/AC inverter - can feed AC power back into the commercial electrical power grid.

Absorption dynamometers can be equipped with two types of control systems to provide different main test types.

Constant Force

The dynamometer has a "braking" torque regulator - the Power Absorption Unit (PAU) is configured to provide a set braking force torque load, while the prime mover is configured to operate at whatever throttle opening, fuel delivery rate, or any other variable it is desired to test. The prime mover is then allowed to accelerate the engine through the desired speed or RPM range. Constant Force test routines require the PAU to be set slightly torque deficient as referenced to prime mover output to allow some rate of acceleration. Power is calculated based on rotational speed x torque x constant. The constant varies depending on the units used.

Constant Speed

If the dynamometer has a speed regulator (human or computer), the PAU provides a variable amount of braking force (torque) that is necessary to cause the prime mover to operate at the desired single test speed or RPM. The PAU braking load applied to the prime mover can be manually controlled or determined by a computer. Most systems employ eddy current, oil hydraulic, or DC motor produced loads because of their linear and quick load change abilities.

Power is calculated based on rotational speed x torque x constant, with the constant varying with the output unit desired and the input units used.

A motoring dynamometer acts as a motor that drives the equipment under test. It must be able to drive the equipment at any speed and develop any level of torque that the test requires. In common usage, AC or DC motors are used to drive the equipment or "load" device.

In most dynamometers power (P) is not measured directly, but must be calculated from torque (τ) and angular velocity (ω)[citation needed] values or force (F) and linear velocity (v):

- or

- where

- P is the power in watts

- τ is the torque in newton metres

- ω is the angular velocity in radians per second

- F is the force in newtons

- v is the linear velocity in metres per second

Division by a conversion constant may be required, depending on the units of measure used.

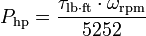

For imperial units,

- where

- Php is the power in horsepower

- τlb·ft is the torque in pound-feet

- ωRPM is the rotational velocity in revolutions per minute

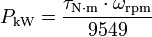

For metric units,

- where

- PkW is the power in kilowatts

- τN·m is the torque in newton metres

- ωrpm is the rotational velocity in revolutions per minute

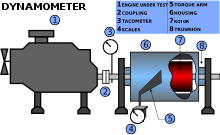

Detailed dynamometer description

A dynamometer consists of an absorption (or absorber/driver) unit, and usually includes a means for measuring torque and rotational speed. An absorption unit consists of some type of rotor in a housing. The rotor is coupled to the engine or other equipment under test and is free to rotate at whatever speed is required for the test. Some means is provided to develop a braking torque between the rotor and housing of the dynamometer. The means for developing torque can be frictional, hydraulic, electromagnetic, or otherwise, according to the type of absorption/driver unit.

One means for measuring torque is to mount the dynamometer housing so that it is free to turn except as restrained by a torque arm. The housing can be made free to rotate by using trunnions connected to each end of the housing to support it in pedestal-mounted trunnion bearings. The torque arm is connected to the dyno housing and a weighing scale is positioned so that it measures the force exerted by the dyno housing in attempting to rotate. The torque is the force indicated by the scales multiplied by the length of the torque arm measured from the center of the dynamometer. A load cell transducer can be substituted for the scales in order to provide an electrical signal that is proportional to torque.

Another means to measure torque is to connect the engine to the dynamometer through a torque sensing coupling or torque transducer. A torque transducer provides an electrical signal that is proportional to the torque.

With electrical absorption units, it is possible to determine torque by measuring the current drawn (or generated) by the absorber/driver. This is generally a less accurate method and not much practiced in modern times, but it may be adequate for some purposes.

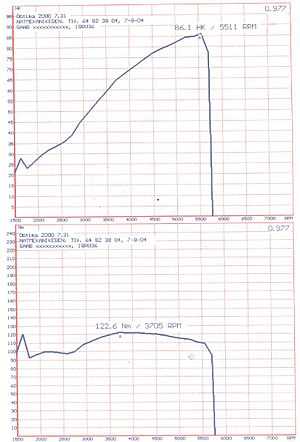

When torque and speed signals are available, test data can be transmitted to a data acquisition system rather than being recorded manually. Speed and torque signals can also be recorded by a chart recorder or plotter.

Types of dynamometers

In addition to classification as Absorption, Motoring, or Universal, as described above, dynamometers can also be classified in other ways.

A dyno that is coupled directly to an engine is known as an engine dyno.

A dyno that can measure torque and power delivered by the power train of a vehicle directly from the drive wheel or wheels (without removing the engine from the frame of the vehicle), is known as a chassis dyno.

Dynamometers can also be classified by the type of absorption unit or absorber/driver that they use. Some units that are capable of absorption only can be combined with a motor to construct an absorber/driver or "universal" dynamometer.

Types of absorption/driver units

- Eddy current or electromagnetic brake (absorption only)

- Magnetic powder brake (absorption only)

- Hysteresis brake (absorption only)

- Electric motor/generator (absorb or drive)

- Fan brake (absorption only)

- Hydraulic brake (absorption only)

- Mechanical friction brake or Prony brake (absorption only)

- Water brake (absorption only)

- Compound dyno (usually an absorption dyno in tandem with an electric/motoring dyno)

Eddy current type absorber

Eddy current (EC) dynamometers are currently the most common absorbers used in modern chassis dynos. The EC absorbers provide a quick load change rate for rapid load settling. Most are air cooled, but some are designed to require external water cooling systems.

Eddy current dynamometers require an electrically conductive core, shaft, or disc moving across a magnetic field to produce resistance to movement. Iron is a common material, but copper, aluminum, and other conductive materials are also usable.

In current (2009) applications, most EC brakes use cast iron discs similar to vehicle disc brake rotors, and use variable electromagnets to change the magnetic field strength to control the amount of braking.

The electromagnet voltage is usually controlled by a computer, using changes in the magnetic field to match the power output being applied.

Sophisticated EC systems allow steady state and controlled acceleration rate operation.

Powder dynamometer

A powder dynamometer is similar to an eddy current dynamometer, but a fine magnetic powder is placed in the air gap between the rotor and the coil. The resulting flux lines create "chains" of metal particulate that are constantly built and broken apart during rotation, creating great torque. Powder dynamometers are typically limited to lower RPM due to heat dissipation problems.

Hysteresis dynamometers

Hysteresis dynamometers use a steel rotor that is moved through flux lines generated between magnetic pole pieces. This design (as in the usual "disc type" eddy current absorbers) allows for full torque to be produced at zero speed, as well as at full speed. Heat dissipation is assisted by forced air. Hysteresis and "disc type" EC dynamometers are one of the most efficient technologies in small (200 hp (150 kW) and less) dynamometers. A hysteresis brake is an eddy current absorber that, unlike most "disc type" eddy current absorbers, puts the electromagnet coils inside a vented and ribbed cylinder and rotates the cylinder, instead of rotating a disc between electromagnets. The potential benefit for the hysteresis absorber is that the diameter can be decreased and operating RPM of the absorber may be increased.

Electric motor/generator dynamometer

Electric motor/generator dynamometers are a specialized type of adjustable-speed drive. The absorption/driver unit can be either an alternating current (AC) motor or a direct current (DC) motor. Either an AC motor or a DC motor can operate as a generator that is driven by the unit under test or a motor that drives the unit under test. When equipped with appropriate control units, electric motor/generator dynamometers can be configured as universal dynamometers. The control unit for an AC motor is a variable-frequency drive, while the control unit for a DC motor is a DC drive. In both cases, regenerative control units can transfer power from the unit under test to the electric utility. Where permitted, the operator of the dynamometer can receive payment (or credit) from the utility for the returned power via net metering.

In engine testing, universal dynamometers can not only absorb the power of the engine, but can also drive the engine for measuring friction, pumping losses, and other factors.

Electric motor/generator dynamometers are generally more costly and complex than other types of dynamometers.

Fan brake

A fan is used to blow air to provide engine load. The torque absorbed by a fan brake may be adjusted by changing the gearing or the fan itself, or by restricting the airflow through the fan. It should be noted that, due to the low viscosity of air, this variety of dynamometer is inherently limited in the amount of torque that it can absorb.

Hydraulic brake

The hydraulic brake system consists of a hydraulic pump (usually a gear-type pump), a fluid reservoir, and piping between the two parts. Inserted in the piping is an adjustable valve, and between the pump and the valve is a gauge or other means of measuring hydraulic pressure. In simplest terms, the engine is brought up to the desired RPM and the valve is incrementally closed. As the pumps outlet is restricted, the load increases and the throttle is simply opened until at the desired throttle opening. Unlike most other systems, power is calculated by factoring flow volume (calculated from pump design specifications), hydraulic pressure, and RPM. Brake HP, whether figured with pressure, volume, and RPM, or with a different load cell-type brake dyno, should produce essentially identical power figures. Hydraulic dynos are renowned for having the quickest load change ability, just slightly surpassing eddy current absorbers. The downside is that they require large quantities of hot oil under high pressure and an oil reservoir.

Water brake-type absorber

The water brake absorber is sometimes mistakenly called a "hydraulic dynamometer". Invented by British engineer William Froude in 1877 in response to a request by the Admiralty to produce a machine capable of absorbing and measuring the power of large naval engines,[2] water brake absorbers are relatively common today. They are noted for their high power capability, small size, light weight, and relatively low manufacturing costs as compared to other, quicker reacting, "power absorber" types.

Their drawbacks are that they can take a relatively long period of time to "stabilize" their load amount, and that they require a constant supply of water to the "water brake housing" for cooling. In many parts of the country, environmental regulations now prohibit "flow through" water, and so large water tanks must be installed to prevent contaminated water from entering the environment.

The schematic shows the most common type of water brake, known as the "variable level" type. Water is added until the engine is held at a steady RPM against the load, with the water then kept at that level and replaced by constant draining and refilling (which is needed to carry away the heat created by absorbing the horsepower). The housing attempts to rotate in response to the torque produced, but is restrained by the scale or torque metering cell that measures the torque.

Compound Dynamometers

In most cases, motoring dynamometers are symmetrical; a 300 kW AC dynamometer can absorb 300 kW as well as motor at 300 kW. This is an uncommon requirement in engine testing and development. Sometimes, a more cost-effective solution is to attach a larger absorption dynamometer with a smaller motoring dynamometer. Alternatively, a larger absorption dynamometer and a simple AC or DC motor may be used in a similar manner, with the electric motor only providing motoring power when required (and no absorption). The (cheaper) absorption dynamometer is sized for the maximum required absorption, whereas the motoring dynamometer is sized for motoring. A typical size ratio for common emission test cycles and most engine development is approximately 3:1. Torque measurement is somewhat complicated since there are two machines in tandem - an inline torque transducer is the preferred method of torque measurement in this case. An eddy-current or waterbrake dynamometer, with electronic control combined with a variable frequency drive and AC induction motor, is a commonly used configuration of this type. Disadvantages include requiring a second set of test cell services (electrical power and cooling), and a slightly more complicated control system. Attention must be paid to the transition between motoring and braking in terms of control stability.

How dynamometers are used for engine testing

Dynamometers are useful in the development and refinement of modern engine technology. The concept is to use a dyno to measure and compare power transfer at different points on a vehicle, thus allowing the engine or drivetrain to be modified to get more efficient power transfer. For example, if an engine dyno shows that a particular engine achieves 400 N·m (295 lbf·ft) of torque, and a chassis dynamo shows only 350 N·m (258 lbf·ft), one would know to look to the drivetrain for the major improvements. Dynamometers are typically very expensive pieces of equipment, and so are normally only used in certain fields that rely on them for a particular purpose.

Types of dynamometer systems

A 'brake' dynamometer applies variable load on the Prime Mover (PM) and measures the PM's ability to move or hold the RPM as related to the "braking force" applied. It is usually connected to a computer that records applied braking torque and calculates engine power output based on information from a "load cell" or "strain gauge" and a speed sensor.

An 'inertia' dynamometer provides a fixed inertial mass load, calculates the power required to accelerate that fixed and known mass, and uses a computer to record RPM and acceleration rate to calculate torque. The engine is generally tested from somewhat above idle to its maximum RPM and the output is measured and plotted on a graph.

A 'motoring' dynamometer provides the features of a brake dyne system, but in addition, can "power" (usually with an AC or DC motor) the Prime Mover (PM) and allow testing of very small power outputs (for example, duplicating speeds and loads that are experienced when operating a vehicle traveling downhill or during on/off throttle operations).

Types of dynamometer test procedures

There are essentially 3 types of dynamometer test procedures:

- Steady state: where the engine is held at a specified RPM (or series of usually sequential RPMs) for a desired amount of time by the variable brake loading as provided by the PAU (power absorber unit). These are performed with brake dynamometers.

- Sweep test: the engine is tested under a load (i.e. inertia or brake loading), but allowed to "sweep" up in RPM, in a continuous fashion, from a specified lower "starting" RPM to a specified "end" RPM. These tests can be done with inertia or brake dynamometers.

- Transient test: usually done with AC or DC dynamometers, the engine power and speed are varied throughout the test cycle. Different test cycles are used in different jurisdictions. Chassis test cycles include the US light-duty UDDS, HWFET, US06, SC03, ECE, EUDC, and CD34, while engine test cycles include ETC, HDDTC, HDGTC, WHTC, WHSC, and ED12.

Types of sweep tests

- Inertia Sweep: an inertia dyno system provides a fixed inertial mass flywheel and computes the power required to accelerate the flywheel (the load) from the starting to the ending RPM. The actual rotational mass of the engine (or engine and vehicle in the case of a chassis dyno) is not known, and the variability of even the mass of the tires will skew the power results. The inertia value of the flywheel is "fixed", so low-power engines are under load for a much longer time and internal engine temperatures are usually too high by the end of the test, skewing optimal "dyno" tuning settings away from the optimal tuning settings of the outside world. Conversely, high powered engines commonly complete a "4th gear sweep" test in less than 10 seconds, which is not a reliable load condition as compared to operation in the real world. By not providing enough time under load, internal combustion chamber temperatures are unrealistically low and power readings - especially past the power peak - are skewed to the low side.

- Loaded Sweep, of the brake dyno type, includes:

- Simple Fixed Load Sweep: a fixed load - of somewhat less than the output of the engine - is applied during the test. The engine is allowed to accelerate from its starting RPM to its ending RPM, varying at its own acceleration rate, depending on power output at any particular rotational speed. Power is calculated using (rotational speed x torque x constant) + the power required to accelerate the dyno and engine's/vehicle's rotating mass.

- Controlled Acceleration Sweep: similar in basic usage as the (above) Simple Fixed Load Sweep Test, but with the addition of active load control that targets a specific rate of acceleration. Commonly, 20fps/ps is used.

- Controlled Acceleration Rate: the acceleration rate used is controlled from low power to high power engines, and overextension and contraction of "test duration" is avoided, providing more repeatable tests and tuning results.

In every type of sweep test, there remains the issue of potential power reading error due to the variable engine/dyno/vehicle total rotating mass. Many modern computer-controlled brake dyno systems are capable of deriving that "inertial mass" value, so as to eliminate this error.

Interestingly, a "sweep test" will almost always be suspect, as many "sweep" users ignore the rotating mass factor, preferring to use a blanket "factor" on every test on every engine or vehicle. Simple inertia dyno systems aren't capable of deriving "inertial mass", and thus are forced to use the same (assumed) inertial mass on every vehicle tested.

Using Steady State testing eliminates the rotating inertial mass error of a sweep test, as there is no acceleration during this type of test.

Transient test characteristics

Aggressive throttle movements, engine speed changes, and engine motoring are characteristics of most transient engine tests. The usual purpose of these tests are vehicle emissions development and homologation. In some cases, the lower-cost eddy-current dynamometer is used to test one of the transient test cycles for early development and calibration. An eddy current dyno system offers fast load response, which allows rapid tracking of speed and load, but does not allow motoring. Since most required transient tests contain a significant amount of motoring operation, a transient test cycle with an eddy-current dyno will generate different emissions test results. Final adjustments are required to be done on a motoring-capable dyno.

Engine dynamometer

An engine dynamometer measures power and torque directly from the engine's crankshaft (or flywheel), when the engine is removed from the vehicle. These dynos do not account for power losses in the drivetrain, such as the gearbox, transmission, and differential.

Chassis dynamometer (rolling road)

A chassis dynamometer, sometimes referred to as a rolling road,[3] measures power delivered to the surface of the "drive roller" by the drive wheels. The vehicle is often parked on the roller or rollers, which the car then turns, and the output measured thereby.

Modern roller-type chassis dyno systems use the "Salvisberg roller",[4] which improves traction and repeatability, as compared to the use of smooth or knurled drive rollers. Chassis dynamometers can be fixed or portable, and can do much more than display RPM, horsepower, and torque. With modern electronics and quick reacting, low inertia dyno systems, it is now possible to tune to best power and the smoothest runs in real time.

Other types of chassis dynamometers are available that eliminate the potential for wheel slippage on old style drive rollers, attaching directly to the vehicle hubs for direct torque measurement from the axle.

Motor vehicle emissions development and homologation dynamometer test systems often integrate emissions sampling, measurement, engine speed and load control, data acquisition, and safety monitoring into a complete test cell system. These test systems usually include complex emissions sampling equipment (such as constant volume samplers and raw exhaust gas sample preparation systems) and analyzers. These analyzers are much more sensitive and much faster than a typical portable exhaust gas analyzer. Response times of well under one second are common, and are required by many transient test cycles. In retail settings it is also common to tune the air-fuel ratio using a wideband oxygen sensor that is graphed along with the RPM.

Integration of the dynamometer control system with automatic calibration tools for engine system calibration is often found in development test cell systems. In these systems, the dynamometer load and engine speed are varied to many engine operating points, while selected engine management parameters are varied and the results recorded automatically. Later analysis of this data may then be used to generate engine calibration data used by the engine management software.

Because of frictional and mechanical losses in the various drivetrain components, the measured rear wheel brake horsepower is generally 15-20 percent less than the brake horsepower measured at the crankshaft or flywheel on an engine dynamometer.[5]

History

The Graham-Desaguliers Dynamometer was invented by George Graham and mentioned in the writings of John Desagulier in 1719.[6] Desaguliers modified the first dynamometers, and so the instrument became known as the Graham-Desaguliers dynamometer.

The Regnier dynamometer was invented and made public in 1798 by Edme Régnier, a French rifle maker and engineer.[7]

A patent was issued (dated June 1817)[8][9] to Siebe and Marriot of Fleet Street, London for an improved weighing machine.

Gaspard de Prony invented the de Prony brake in 1821.

Macneill's road indicator was invented by John Macneill in the late 1820s, further developing Marriot's patented weighing machine.

Froude Hofmann, of Worcester, UK, manufactures engine and vehicle dynamometers. They credit William Froude with the invention of the hydraulic dynamometer in 1877, and say that the first commercial dynamometers were produced in 1881 by their predecessor company, Heenan & Froude.

In 1928, the German company "Carl Schenck Eisengießerei & Waagenfabrik" built the first vehicle dynamometers for brake tests that have the basic design of modern vehicle test stands.

The eddy current dynamometer was invented by Martin and Anthony Winther around 1931, but at that time, DC Motor/generator dynamometers had been in use for many years. A company founded by the Winthers brothers, Dynamatic Corporation, manufactured dynamometers in Kenosha, Wisconsin until 2002. Dynamatic was part of Eaton Corporation from 1946 to 1995. In 2002, Dyne Systems of Jackson, Wisconsin acquired the Dynamatic dynamometer product line. Starting in 1938, Heenan & Froude manufactured eddy current dynamometers for many years under license from Dynamatic and Eaton.[10]

See also

- Dynamometer car for railroad usage

- Engine test stand dynamometer for engines (e.g. combustion engines)

- Hand strength dynamometer

- Machine tool dynamometer

- Miles per gallon

- Universal testing machine

Notes

- ↑ health.uottawa.ca, Dynamometry

- ↑ "History | About Us". Froude Hoffmann. Retrieved 9 Jan 2013.

- ↑ "Rolling Road Dyno". Tuning Tools. Retrieved 3 August 2012.

- ↑ uspto.gov

- ↑ John Dinkel, "Chassis Dynamometer", Road and Track Illustrated Automotive Dictionary, (Bentley Publishers, 2000) p. 46.

- ↑ Burton, Allen W. and Daryl E. Miller, 1998, Movement Skill Assessment

- ↑ Régnier, Edmé. Description et usage du dynamomètre, 1798.

- ↑ 's+patent+weighing+machine&hl=no&ei=L-XITq_lLaiB4ASfo5jcAg&sa=X&oi=book_result&ct=result&resnum=2&ved=0CEwQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=marriott's%20patent%20weighing%20machine&f=false Marriot's patent weighing machine

- ↑ Marriott's improved weighing machine

- ↑ Winther, Martin P. (1976). Eddy Currents. Cleveland, Ohio: Eaton Corporation.

References

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dynamometers. |

- Winther, J. B. (1975). Dynamometer Handbook of Basic Theory and Applications. Cleveland, Ohio: Eaton Corporation.

- Martyr, A.; Plint, M. (2007). Engine Testing - Theory and Practice (Fourth ed.). Oxford, UK: ELSEVIER. ISBN 978-0-08-096949-7.