Dutch people

1st row: Erasmus • William of Orange • Johan van Oldenbarnevelt • Maurice of Nassau • Piet Heyn 2nd row: Grotius • Frederick Henry of Orange • Jan Leeghwater • Rembrandt • Michiel de Ruyter 3rd row: Johan de Witt • Spinoza • Christiaan Huygens • William III of Orange • Antonie van Leeuwenhoek 4th row: Belle van Zuylen • Thorbecke • Multatuli • Vincent van Gogh • Johannes van der Waals 5th row: Hendrik Lorentz • Aletta Jacobs • Wilhelmina • Willem Drees • Johan Cruyff | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

|

16–25 million (est.)[3] (~23 million native Dutch speakers worldwide) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|

13,236,618 (Ethnic Dutch) ~472,600[4] (Dutch Indonesians) | |

| 7,000,000 (Dutch ancestry)[5][6] | |

| 5,087,191 (Dutch ancestry)[5] | |

| 1,000,000(Dutch ancestry)[7] | |

| 1,000,000 (Dutch ancestry)[8] | |

| 350,000 (Dutch nationals)[9] | |

| 335,500 (Dutch ancestry)[10] | |

| 120,970[11] | |

| est. 100,000[12] | |

| est. 30,000[13] | |

| est. 20,000[14] | |

| est. 15,000[15] | |

| 15,000[13] | |

| est. 13,000[16] | |

| est. 10,000[13] | |

The Dutch people (Dutch: ![]() Nederlanders (help·info)), occasionally referred to as Netherlanders, are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands.[17][18] They share a common culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Suriname, Chile, Brazil, Canada,[19] Australia,[20] South Africa,[21] New Zealand, and the United States.[22]

Nederlanders (help·info)), occasionally referred to as Netherlanders, are an ethnic group native to the Netherlands.[17][18] They share a common culture and speak the Dutch language. Dutch people and their descendants are found in migrant communities worldwide, notably in Suriname, Chile, Brazil, Canada,[19] Australia,[20] South Africa,[21] New Zealand, and the United States.[22]

The traditional art and culture of the Dutch encompasses various forms of traditional music, dances, architectural styles and clothing, some of which are globally recognizable. Internationally, Dutch painters such as Rembrandt, Vermeer and Van Gogh are held in high regard. The dominant religion of the Dutch is Christianity (both Catholic and Protestant), although in modern times the majority is no longer religious. Significant percentages of the Dutch are adherents of humanism, agnosticism, atheism or individual spirituality.[23][24]

In the Middle Ages the Low Countries were situated around the border of France and the Holy Roman Empire, forming a part of their respective peripheries, and the various territories of which they consisted had de facto become virtually autonomous by the 13th century.[25] Under the Habsburgs, the Netherlands were organised into a single administrative unit, and in the 16th and 17th centuries the Northern Netherlands gained independence from Spain as the Dutch Republic.[26] The high degree of urbanization characteristic of Dutch society was attained at a relatively early date.[27] During the Republic the first series of large scale Dutch migrations outside of Europe took place.

History

Emergence

As with all ethnic groups the ethnogenesis of the Dutch (and their predecessors) has been a lengthy and complex process. Though the majority of the defining characteristics (such as language, religion, architecture or cuisine) of the Dutch ethnic group have accumulated over the ages, it is difficult (if not impossible) to clearly pinpoint the exact emergence of the Dutch people; the interpretation of which is often highly personal. The text below hence focuses on the history of the Dutch ethnic group; for Dutch national history, please see the history-articles of the Netherlands. For Dutch colonial history, see the article on the Dutch Empire.

General

In the first centuries CE, the Germanic tribes formed tribal societies with no apparent form of autocracy (chiefs only being elected in times of war), beliefs based Germanic paganism and speaking a dialect still closely resembling Common Germanic. Following the end of the migration period in the West around 500, with large federations (such as the Franks, Vandals, Alamanni and Saxons) settling the decaying Roman Empire, a series of monumental changes took place within these Germanic societies. Among the most important of these are their conversion from Germanic paganism to Christianity, the emergence of a new political system, centered on kings, and a continuing process of emerging mutual unintelligibility of their various dialects.

Specific

The general situation described above is applicable to most if not all modern European ethnic groups with origins among the Germanic tribes, such as the Frisians, Germans, English and the North-Germanic peoples. In the Low Countries, this phase began when the Franks, themselves a union of multiple smaller tribes (many of them, such as the Batavi, Chauci, Chamavi and Chattuarii, were already living in the Low Countries prior to the forming of the Frankish confederation), began to incur the northwestern provinces of the Roman Empire. Eventually, in 358, the Salian Franks, one of the three main subdivisions among the Frankish alliance[28] settled the area's Southern lands as a foederati; Roman allies in charge of border defense.[29]

Linguistically Old Frankish gradually evolved into Old Dutch,[30][31] which was first attested in the 6th century,[32] whereas religiously the Franks (beginning with the upper class) converted to Christianity from around 500 to 700. On a political level, the Frankish warlords abandoned tribalism[33] and founded a number of kingdoms, eventually culminating in the Frankish Empire of Charlemagne.

However, the population make-up of the Frankish Empire, or even early Frankish kingdoms such as Neustria and Austrasia, was not dominated by Franks. Though the Frankish leaders controlled most of Western Europe, the Franks themselves were confined to the Northwestern part (i.e the Low Countries and Northern France) of the Empire.[34] Eventually, the Franks in Northern France were assimilated by the general Gallo-Roman population, and took over their dialects (which became French), whereas the Franks in the Low Countries retained their language, which would evolve into Dutch. The current Dutch-French language border has (with the exception of the Nord-Pas-de-Calais in France and Brussels and the surrounding municipalities in Belgium) remained virtually identical ever since, and could be seen as marking the furthest pale of gallicization among the Franks.[35]

Convergence

The medieval cities of the Low Countries, who experienced major growth during the 11th and 12th century, were instrumental in breaking down the already relatively loose local form of feudalism. As they became increasingly powerful, they used their economical strength to influence the politics of their nobility.[36][37][38] During the early 14th century, beginning in and inspired by the County of Flanders,[39] the cities in the Low Countries gained huge autonomy and generally dominated or greatly influenced the various political affairs of the fief, including marriage succession.

While the cities were of great political importance, they also formed catalysts for medieval Dutch culture. Trade flourished, population numbers increased dramatically, and (advanced) education was no longer limited to the clergy; Dutch epic literature such as Elegast (1150), the Roelantslied and Van den vos Reynaerde (1200) were widely enjoyed. The various city guilds as well as the necessity of water boards (in charge of dikes, canals, etc.) in the Dutch delta and coastal regions resulted in an exceptionally high degree of communal organization. It is also around this time, that ethnonyms such as Diets and Nederlands emerge.[40]

In the second half of the 14th century, the dukes of Burgundy gained a foothold in the Low Countries through the marriage in 1369 of Philip the Bold of Burgundy to the heiress of the Count of Flanders. This was followed by a series of marriages, wars, and inheritances among the other Dutch fiefs and around 1450 the most important fiefs are under Burgundian rule, while complete control is achieved in 1503, thereby unifying the fiefs of the Low Countries under one ruler. This process marks a new episode in the development of the Dutch ethnic group, as now political unity starts to emerge, consolidating the strengthened cultural and linguistic unity.

Consolidation

Despite the linguistic and cultural unity, and (in the case of Flanders, Brabant and Holland) economical similarities; there was still little sense of political unity among the Dutch.[41]

However, the centralist policies of Burgundy in the 14th and 15th centuries, at first violently opposed by the cities of the Low Countries, had a profound impact and changed this. During Charles the Bold's many wars, which were a major economic burden for the Burgundian Netherlands, tensions slowly increased. In 1477, the year of Charles' sudden death at Nancy, the Low Countries rebeled against their new liege, Mary of Burgundy and presented her with a set of demands.

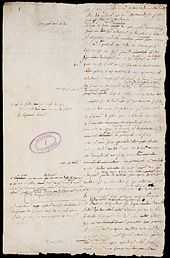

The subsequently issued great privilege met a lot of these demands (which included that Dutch, not French, should be the administrative language in the Dutch-speaking provinces and that the States General had the right to hold meetings without the monarch's permission or presence) and despite the fact that the overall tenure of the document (which was declared void by her son, and successor, Philip IV) aimed for more autonomy for the counties and duchies, the fact that all fiefs presented their demands together, rather than separately, are evidence that by this time a sense of common interest was emerging among the provinces of the Netherlands.[42]

Following Mary's marriage to Maximilian I, Holy Roman Emperor, the Netherlands were now part of the Habsburg lands. Further centralized policies by the Habsburgs (like their Burgundian predecessors) again met with resistance, but, peaking with the formation of the collateral councils of 1531 and the Pragmatic Sanction of 1549, were still implemented. The rule of Philip II of Spain sought even further centralist reforms, which, accompanied by religious dictates and excessive taxation, resulted in the Dutch Revolt. The Dutch provinces, though fighting alone now, for the first time in their history found themselves fighting a common enemy. This, together with the growing number of Dutch intelligentsia and the Dutch Golden Age in which Dutch culture, as a whole, would get international prestige, consolidated the Dutch as an ethnic group.

National identity

By the middle of the 16th century an overarching, 'national' (rather than 'ethnic') identity seemed in development in the Habsburg Netherlands, when inhabitants began to refer to it as their 'fatherland' and were beginning to be seen as a collective entity abroad; however, the persistence of language barriers, traditional strife between towns, and provincial particularism continued to form an impediment to more thorough unification.[43] Following excessive taxation together with attempts at diminishing the traditional autonomy of the cities and estates in the Low Countries, followed by the religious oppression after being transferred to Habsburg Spain, the Dutch revolted, in what would become the Eighty Years' War. For the first time in their history, the Dutch established their independence from foreign rule.[44] However, during the war it became apparent that the goal of liberating all the provinces and cities that had signed the Union of Utrecht, which roughly corresponded to the Dutch-speaking part of the Spanish Netherlands, was unreachable. The Northern provinces were free, but during the 1580s the South was recaptured by Spain, and, despite various attempts, the armies of the Republic were unable to expel them. In 1648, the Peace of Münster, ending the Eighty Years' War, acknowledged the independence of the Dutch Republic, but maintained Spanish control of the Southern Netherlands. Apart from a brief reunification from 1815 until 1830, within the United Kingdom of the Netherlands (which included the Francophones/Walloons) the Dutch have been separated from the Flemings to this day.

Ethnic identity

The ideologies associated with (Romantic) Nationalism of the 19th and 20th centuries never really caught on in the Netherlands, and this, together with being a relatively mono-ethnic society up until the late 1950s, has led to a relatively obscure use of the terms nation and ethnicity as both were largely overlapping in practice. Today, despite other ethnicities making up 19.6% of the Netherlands' population, this obscurity continues in colloquial use, in which Nederlander sometimes refers to the ethnic Dutch, sometimes to anyone possessing Dutch citizenship.[45] In addition to this, many Dutchmen will object to being called Hollanders as a national denominator on much of the same grounds that many Welshmen or Scots would object to being called English instead of British.

However, the (re)definition of Dutch cultural identity has become a subject of public debate in recent years following the increasing influence of the European Union and the influx of non-Western immigrants in the post-World War II period. In this debate 'typically Dutch traditions' have been put to the foreground.[46]

In sociological studies and governmental reports, ethnicity is often referred to with the terms autochtoon and allochtoon.[47] These legal concepts refer to place of birth and citizenship rather than cultural background and do not coincide with the more fluid concepts of ethnicity used by cultural anthropologists.

Greater Netherlands

As did many European ethnicities during the 19th century,[48] the Dutch also saw the emerging of various Greater Netherlands- and pan-movements seeking to unite the Dutch-speaking peoples across the continent. During the first half of the 20th century, there was a prolific surge in writings concerning the subject. One of its most active proponents was the historian Pieter Geyl, who wrote De Geschiedenis van de Nederlandsche stam (Dutch: The History of the Dutch tribe/people) as well as numerous essays on the subject.

During World War II, when both Belgium and the Netherlands fell to German occupation, fascist elements (such as the NSB and Verdinaso) tried to convince the Nazis into combining the Netherlands and Flanders. The Germans however refused to do so, as this conflicted with their ultimate goal of a 'Germanic Europe'.[49] During the entire Nazi occupation, the Germans denied any assistance to Greater Dutch ethnic nationalism, and, by decree of Hitler himself, actively opposed it.[50]

The 1970s marked the beginning of formal cultural and linguistic cooperation between Belgium (Flanders) and the Netherlands on an international scale.

Statistics

The total number of Dutch can be defined in roughly two ways. By taking the total of all people with full Dutch ancestry, according to the current CBS definition, resulting in an estimated 16,000,000 Dutch people,[51] or by the sum of all people with both full and partial Dutch ancestry, which would result in a number around 25,000,000.

Dutch-speakers in Europe |

People of Dutch ancestry outside the Netherlands and Belgium. |

Linguistics

Language

.png)

Dutch is the language spoken by most Dutch people. It is a West Germanic language spoken by around 22 million people. The language was first attested around 500,[52] in a Frankish legal text, the Lex Salica, and has a written record of more than 1500 years, although the material before c. 1200 is fragmentary and discontinuous.

As a West Germanic language, Dutch is related to other languages in that group such as Frisian, English and German. Many West Germanic dialects experienced a series of sound shifts. The Anglo-Frisian nasal spirant law and Anglo-Frisian brightening resulted in certain early Germanic languages evolving into what are now English and Frisian, while the Second Germanic sound shift resulted in what would become German. Dutch experienced none of these sound changes and can thus be said to occupy a central position within the West Germanic languages.

Standard Dutch has a sound inventory of 13 vowels, 6 diphthongs and 23 consonants, of which the voiceless velar fricative (hard ch) is considered a well known sound, perceived as typical for the language. Other relatively well known features of the Dutch language and use are the frequent use digraphs like Oo, Ee, Uu and Aa, the ability to form long compounds and the use of diseases as profanity.

General consensus among linguists is that the Dutch language has 28 main dialects. These dialects are usually grouped into six main categories; Hollandic, West-Flemish/Zealandic, East Flemish, Brabantic, Limburgish and Dutch Saxon.[53] Of these dialects, Brabantic and East Flemish are spoken exclusively by the Southern Dutch, whereas Hollandic and Dutch Saxon are solely spoken by Northerners. West-Flemish/Zealandic and Limburgish are cross border dialects in this respect. Lastly, the dialectal situation is characterised by the major distinction between 'Hard G' and 'Soft G' speaking areas (see also Dutch phonology).

Dutch immigrants also exported the Dutch language. Dutch was spoken in United States as a native language from the arrival of the first permanent Dutch settlers in 1615, surviving in isolated ethnic pockets until ~1900, when it ceased to be spoken with the exception of 1st generation Dutch immigrants. The Dutch language nevertheless had a significant impact on the region around New York. For example, the first language of American president Martin Van Buren was Dutch.[54] Most of the Dutch immigrants of the 20th century quickly began to speak the language of their new country. For example, of the inhabitants of New Zealand, 0.7% say their home language is Dutch,[55] despite the percentage of Dutch heritage being considerably higher.[56]

Dutch is currently an official language of the Netherlands, Belgium, Suriname, Aruba, Sint Maarten, Curaçao, the European Union and the Union of South American Nations (due to Suriname being a member). In South Africa, Afrikaans is spoken, a daughter language of Dutch, which itself was an official language of South Africa until 1983. The Dutch, Flemish and Surinamese governments coordinate their language activities in the Nederlandse Taalunie (Dutch Language Union), an institution also responsible for governing the Dutch Standard language, for example in matters of orthography.

Etymology of autonym and exonym

The origins of the word Dutch go back to Proto-Germanic, the ancestor of all Germanic languages, *theudo (meaning "national/popular"); akin to Old Dutch dietsc, Old High German diutsch, Old English þeodisc and Gothic þiuda all meaning "(of) the common (Germanic) people". As the tribes among the Germanic peoples began to differentiate its meaning began to change. The Anglo-Saxons of England for example gradually stopped referring to themselves as þeodisc and instead started to use Englisc, after their tribe. On the continent *theudo evolved into two meanings: Diets (meaning "Dutch (people)" (archaic)[57] and Deutsch (German, meaning "German (people)"). At first the English language used (the contemporary form of) Dutch to refer to any or all of the Germanic speakers on the European mainland (e.g. the Dutch, the Frisians and the -various- Germans). Gradually its meaning shifted to the Germanic people they had most contact with, both because of their geographical proximity, but also because of the rivalry in trade and overseas territories: the people from the Republic of the Netherlands, the Dutch.[58]

In the Dutch language, the Dutch refer to themselves as Nederlanders. Nederlanders derives from the Dutch word "Neder", a cognate of English "Nether" both meaning "low", and "near the sea" (same meaning in both English and Dutch), a reference to the geographical texture of the Dutch homeland; the western portion of the North European Plain.[59][60][61] Although not as old as Diets, the term Nederlands has been in continuous use since 1250.[40]

Names

Dutch surnames (and surnames of Dutch origin) are generally easily recognizable. There are several main types of surnames in Dutch:

- Patronymic surnames; the name is based on the personal name of the father of the bearer. Historically this has been by far the most dominant form. These type of names fluctuated in form as the surname was not constant. If a man called Willem Janssen (William, John's son) had a son named Jacob, he would be known as Jacob Willemsen (Jacob, Williams' son). Following civil registry, the form at time of registry became permanent. Hence today many Dutch people are named after ancestors living in the early 19th century when civil registry was introduced to the Low Countries. These names rarely feature tussenvoegsels.

- Toponymic surnames; the name is based on the location on which the bearer lives or lived. In Dutch this form of surname nearly always includes one or several tussenvoegsels, mainly van, van de and variants. Many immigrants removed the spacing, leading to derived names for well known people like Cornelius Vanderbilt.[62] While "van" denotes "of", Dutch surnames are sometimes associated with the upper class of society or aristocracy (cf. William of Orange). However, in Dutch van often reflects the original place of origin (Van Der Bilt - He who comes from De Bilt); rather than denote any aristocratic status.[63]

- Occupational surnames; the name is based on the occupation of the bearer. Well known examples include Molenaar, Visser and Smit. This practice is similar to English surnames (the example names translate perfectly to Miller, Fisher and Smith).[64]

- Cognominal surnames; based on nicknames relating to physical appearance/other features, on the appearance or character of the bearer (at least at the time of registration). For example "De Lange" (the tall one), "De Groot" (the big one), "De Dappere" (the brave one).

- Other surnames may relate to animals. For example; De Leeuw (The Lion), Vogels (Birds), Koekkoek (Cuckoo) and Devalck (The Falcon); to a desired social status; e.g., Prins (Prince), De Koninck/Koning (King), De Keyzer/keizer (Emperor). There is also a set of made up or descriptive names; e.g. Naaktgeboren (born naked).

Dutch names can differ greatly in spelling. The surname Baks, for example is also recorded as Backs, Bacxs, Bakx, Baxs, Bacx, Backx, Bakxs and Baxcs. Though written differently, pronunciation remains identical. Dialectal variety also commonly occurs, with De Smet and De Smit both meaning Smith for example. Surnames of Dutch migrants in foreign environments (mainly the Anglosphere and Francophonie) are often adapted, not only in pronunciation but also in spelling.

Culture

Religion

Prior to the arrival of Christianity, the ancestors of the Dutch adhered to a form of Germanic paganism augmented with various Celtic elements. At the start of the 6th century, the first (Hiberno-Scottish) missionaries arrived. They were later replaced by Anglo-Saxon missionaries, who eventually succeeded in converting most of the inhabitants by the 8th century.[65] Since then, Christianity has been the dominant religion in the region.

In the early 16th century, the Protestant Reformation began to form and soon spread in the Westhoek and the County of Flanders, where secret open-air sermons were held, called hagenpreken ("hedgerow orations") in Dutch. The ruler of the Dutch regions, Philip II of Spain, felt it was his duty to fight Protestantism and, after the wave of iconoclasm, sent troops to crush the rebellion and make the Low Countries a Catholic region once more.[66] The Protestants in the southern Low Countries fled North en masse.[66] Most of the Dutch Protestants were now concentrated in the free Dutch provinces north of the river Rhine, while the Catholic Dutch were situated in the Spanish-occupied or -dominated South. After the Peace of Westphalia in 1648, Protestantism did not spread South, resulting in a difference in religious situations that lasts to this day.

Contemporary Dutch are generally nominally Christians.[67][68] People of Dutch ancestry in the United States are generally more religious than their European counterparts; for example, the numerous Dutch communities of western Michigan remain strongholds of the Reformed Church in America and the Christian Reformed Church, both descendants of the Dutch Reformed Church.

Cultural divergences

One cultural division within Dutch culture is that between the Protestant North and the Catholic South, which encompasses various cultural differences between the Northern Dutch on one side and the Southern Dutch on the other. This subject has historically received attention from historians, notably Pieter Geyl (1887–1966) and Carel Gerretson (1884–1958). The historical pluriformity of the Dutch cultural landscape has given rise to several theories aimed at both identifying and explaining cultural divergences between different regions. One theory, proposed by A.J. Wichers in 1965, sees differences in mentality between the southeastern, or 'higher', and northwestern, or 'lower' regions within the Netherlands, and seeks to explain these by referring to the different degrees to which these areas were feudalised during the Middle Ages.[69] Another, more recent cultural divide is that between the Randstad, the urban agglomeration in the West of the country, and the other provinces of the Netherlands.

In Dutch, the cultural division between North and South is also referred to by the colloquialism "below/above the great rivers" as the rivers Rhine and Meuse roughly form a natural boundary between the Northern Dutch (those Dutch living North of these rivers), and the Southern Dutch (those living South of them). The division is partially caused by (traditional) religious differences, with the North predominantly Protestant and the South having a majority of Catholics. Linguistic (dialectal) differences (positioned along the Rhine/Meuse rivers [sic].) and to a lesser extent, historical economic development of both regions are also important elements in any dissimilarity.

On a smaller scale cultural pluriformity can also be found; be it in local architecture or (perceived) character. This wide array of regional identities positioned within such a relatively small area, has often been attributed to the fact that many of the current Dutch provinces were de facto independent states for much of their history, as well as the importance of local Dutch dialects (which often largely correspond with the provinces themselves) to the people who speak them.[70]

Northern Dutch culture

Frisians

Frisians, specifically West Frisians, are an ethnic group; present in the North of the Netherlands; mainly concentrating in the Province of Friesland. Culturally, modern Frisians and the (Northern) Dutch are rather similar; the main and generally most important difference being that Frisians speak West Frisian, one of the three sub-branches of the Frisian languages, alongside Dutch.

West Frisians in the general do not feel or see themselves as part of a larger group of Frisians, and, according to a 1970 inquiry, identify themselves more with the Dutch than with East or North Frisians.[72] Because of centuries of cohabitation and active participation in Dutch society, as well as being bilingual, the Frisians are not treated as a separate group in Dutch official statistics.

Southern Dutch culture

The Southern Dutch sphere generally consists of the areas in which the population was traditionally Catholic. During the early Middle Ages up until the Dutch Revolt, the Southern regions were more powerful, as well as more culturally and economically developed.[71] At the end of the Dutch Revolt, it became clear the Habsburgs were unable to reconquer the North, while the North's military was too weak to conquer the South, which, under the influence of the Counter-Reformation, had started to develop a political and cultural identity of its own.[73] The Southern Dutch, including Dutch Brabant and Limburg, remained Catholic or returned to Catholicism. The Dutch dialects spoken by this group are Brabantic, Limburgish and East and West Flemish. In the Netherlands, an oft-used adage used for indicating this cultural boundary is the phrase boven/onder de rivieren (Dutch: above/below the rivers), in which 'the rivers' refer to the river Rhine and Meuse. Southern Dutch culture has been influenced more by French culture, opposed to more German influence in the Northern Dutch culture area.[74]

Flemings

Within the field of ethnography, it is argued that the Dutch-speaking populations of the Netherlands and Belgium have a number of common characteristics, with a mostly shared language, some generally similar or identical customs, and with no clearly separate ancestral origin or origin myth.[75]

However, the popular perception of being a single group varies greatly, depending on subject matter, locality, and personal background. Generally, the Flemish will seldom identify themselves as being Dutch and vice versa, especially on a national level.[76] This is partly caused by the popular stereotypes in the Netherlands as well as Flanders, which are mostly based on the "cultural extremes" of both Northern and Southern culture. Though these stereotypes tend to ignore the transitional area formed by the Southern provinces of the Netherlands and most Northern reaches of Belgium, resulting in overgeneralizations.[77]

In the case of Belgium, there is the added influence of nationalism as the Dutch language and culture were oppressed by the francophone government. This was followed by a nationalist backlash during the late 19th and early 20th centuries that saw little help from the Dutch government (which for a long time following the Belgian Revolution had a reticent and contentious relationship with the newly formed Belgium and a largely indifferent attitude towards its Dutch-speaking inhabitants)[78] and, hence, focused on pitting Flemish culture against "French culture", resulting in the forming of the Flemish nation within Belgium, a consciousness of which can be very marked among some Dutch-speaking Belgians.[79]

Dutch diaspora

Since World War II, Dutch Emigrants mainly went to the United States, Canada, Australia, New Zealand, and (until the 1970s) to South Africa. Today Dutch immigrants can be found in most developed countries. In several former Dutch colonies and trading settlements, there are isolated ethnic groups of full or partial Dutch ancestry.

Central and Eastern Europe

During the German eastward expansion (mainly taking place between the 10th and 13th century),[80] a number of Dutchmen moved as well. They settled mainly east of the Elbe and Saale rivers, regions largely inhabited by Polabian Slavs[81] After the capture of territory along the Elbe and Havel Rivers in the 1160s, Dutch settlers from flooded regions in Holland used their expertise to build dikes in Brandenburg, but also settled in and around major German cities such as Bremen and Hamburg and German regions of Mecklenburg and Brandenburg.[82] From the 13th to the 15th centuries, Prussia invited several waves of Dutch and Frisians to settle throughout the country (mainly along the Baltic Sea coast)[83]

In the early-to-mid-16th century, Mennonites began to move from the Low Countries (especially Friesland and Flanders) to the Vistula delta region in Royal Prussia, seeking religious freedom and exemption from military service.[84] After the partition of Poland, the Prussian government took over and its government eliminated exemption from military service on religious grounds. The Mennonites emigrated to Russia. They were offered land along the Volga River. Some settlers left for Siberia in search for fertile land.[85] The Russian capital itself, Moscow, also had a number of Dutch immigrants, mostly working as craftsmen. Arguably the most famous of which was Anna Mons, the mistress of Peter the Great.

Historically Dutch also lived directly on the eastern side of the German border, most have since been assimilated (apart from ~40,000 recent border migrants), especially since the establishment of Germany itself in 1872. Cultural marks can still be found though. In some villages and towns a Dutch Reformed church is present, and a number of border districts (such as Cleves, Borken and Viersen) have towns and village with an etymologically Dutch origin. In the area around Cleves (Ger.Kleve, Du. Kleef) traditional dialect is Dutch, rather than surrounding (High/Low) German. More to the South, cities historically housing many Dutch traders have retained Dutch exonyms for example Aachen (Aken) and Cologne/Köln (Keulen) to this day.

Southern Africa

Although Portuguese explorers made contact with the Cape of Good Hope as early as 1488, much of present-day South Africa was ignored by Europeans until the Dutch East India Company established its first outpost at Cape Town, in 1652.[86][87] Dutch settlers began arriving shortly thereafter, making the Cape home to the oldest Western-based civilisation south of the Sahara.[88] Some of the earliest mulatto communities in the country were subsequently formed through unions between colonists, their slaves, and various Hottentot tribes.[89] This led to the development of a major South African ethnic group, Cape Coloureds, who adopted the Dutch language and culture.[87] As the number of Europeans - particularly females - in the Cape swelled, South African whites closed ranks as a community to protect their privileged status, eventually marginalising 'Coloureds' as a separate and inferior racial group.[90]

Since Company employees proved inept farmers, tracts of land were granted to Dutch and German peasants under the understanding that they would develop their farms as vassals.[88] Upon the revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685, they were joined by French Huguenots fleeing religious persecution at home, who interspersed among the original freemen.[86] Some trekboers eventually turned to cattle ranching, creating their own distinct sub-culture centered around a semi-nomadic lifestyle and isolated patriarchal communities.[88] By the eighteenth century there had emerged a new people in Africa who identified as "Afrikaners" which literally in Dutch translate into African, rather than Dutchmen, after the land they had permanently adopted.[91]

Afrikaners are dominated by two main groups, the Cape Dutch and Boers, which are partly defined by different traditions of society, law, and historical economic bases.[88] Although their language (Afrikaans) and religion remain undeniably linked to that of the Netherlands,[92] Afrikaner culture has been strongly shaped by three centuries in South Africa.[91] Afrikaans, which developed from Middle Dutch, has been influenced by English, French, German, Malay-Portuguese creole, and various African tongues. Although Dutch was taught to South African students as late as 1914, and a few upper-class Afrikaners used it in polite society, the first Afrikaans literature had already appeared in 1861.[88] The Union of South Africa granted Dutch official status upon its inception, but in 1925 Parliament openly recognised Afrikaans as a separate language.[88] It differs from Standard Dutch by several pronunciations borrowed from French, Malay, German, or English, the loss of case and gender distinctions, and in the extreme simplification of grammar (e.g. voël becomes vogel, and reën becomes regen).[93] The dialects are no longer considered quite mutually intelligible.[94]

Southeast Asia

Since the 16th century, there has been a Dutch presence in South East Asia, Taiwan and Japan. In many cases the Dutch were the first Europeans the natives would encounter. Between 1602 and 1796, the VOC sent almost a million Europeans to work in the Asia.[95] The majority died of disease or made their way back to Europe, but some of them made the Indies their new home.[96] Interaction between the Dutch and native population mainly took place in Sri Lanka and the modern Indonesian Islands. Most of the time Dutch soldiers intermarried with local women and settled down in the colonies. Through the centuries there developed a relatively large Dutch-speaking population of mixed Dutch and Indonesian descent, known as Indos or Dutch-Indonesians. The expulsion of Dutchmen following the Indonesian Revolt, means that currently the majority of this group lives in the Netherlands. Statistics show that Indos are in fact the largest minority group in the Netherlands and number close to half a million (excluding the third generation).[97]

Australia and New Zealand

Though the Dutch were the first Europeans to visit Australia and New Zealand, colonization did not take place and it was only after World War II that a sharp increase in Dutch emigration to Australia occurred. Poor economic prospects for many Dutchmen as well as increasing demographic pressures, in the post-war Netherlands were a powerful incentive to emigrate. Due to Australia experiencing a shortage of agricultural and metal industry workers it, and to a lesser extent New Zealand, seemed an attractive possibility, with the Dutch government actively promoting emigration.[98]

The effects of Dutch migration to Australia can still be felt. There are many Dutch associations and a Dutch-language newspaper continues to be published. The Dutch have remained a tightly knit community, especially in the large cities. In total, about 310,000 people of Dutch ancestry live in Australia whereas New Zealand has some 100,000 Dutch descendants.[98]

North America

(in attire typical of the South Beveland island of Zealand)

The Dutch had settled in America long before the establishment of the United States of America.[99] For a long time the Dutch lived in Dutch colonies, owned and regulated by the Dutch Republic, which later became part of the Thirteen Colonies.

Nevertheless, many Dutch communities remained virtually isolated towards the rest of America up until the American Civil War, in which the Dutch fought for the North and adopted many American ways.[100]

Most future waves of Dutch immigrants were quickly assimilated. There have been three American presidents of Dutch descent: Martin Van Buren (8th, first president who was not of British descent, first language was Dutch), Franklin D. Roosevelt (32nd, elected to four terms in office, he served from 1933 to 1945, the only U.S. president to have served more than two terms) and Theodore Roosevelt (26th).

In Canada 923,310 Canadians claim full or partial Dutch ancestry. The first Dutch people to come to Canada were Dutch Americans among the United Empire Loyalists. The largest wave was in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, when large numbers of Dutch helped settle the Canadian west. During this period significant numbers also settled in major cities like Toronto.

While interrupted by World War I, this migration returned in the 1920s, but again halted during the Great Depression and World War II. After the war a large number of Dutch immigrants moved to Canada, including a number of war brides of the Canadian soldiers who liberated the Low Countries.

See also

- Dutch Brazil

- Dutch Chilean

- Dutch customs and etiquette

- Dutch Surinamese

- List of Dutch people

- List of Germanic peoples

- Netherlands (terminology)

- New Netherlands now called New York.

- Pennsylvania Dutch

Notes

- ↑ Estimate based on the population of the Netherlands, without the Southern Provinces and non-Ethnic Dutch.

References

- ↑ 'Clovis' conversion to Christianity, regardless of his motives, is a turning point in Dutch history as the elite now changed their beliefs. Their choice would way down its way on the common folk, of whom many (especially in the Frankish heartland of Brabant and Flanders) were less enthousiastic than the ruling class. Taken from Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse stam, part I: till 1648. Page 203, 'A new religion', by Pieter Geyl. Wereldbibliotheek Amsterdam/Antwerp 1959.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 This image is based on the rough definition given by in the 2005 " number 3" edition of the magazine "Neerlandia" by the ANV; it states the dividing line between both areas lies where "the great rivers divide the Brabantic from the Hollandic dialects and where Protestantism traditionally begins".

- ↑ In the 1950s (the peak of traditional emigration) about 350,000 people left the Netherlands, mainly to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and South Africa. About one-fifth returned. The maximum Dutch-born emigrant stock for the 1950s is about 300,000 (some have died since). The maximum emigrant stock (Dutch-born) for the period after 1960 is 1.6 million. Discounting pre-1950 emigrants (who would be about 85 or older), at most around 2 million people born in the Netherlands are now living outside the country. Combined with the 13,1 million ethnically Dutch inhabitants of the Netherlands, there are about 16 million people who are Dutch, in a minimally accepted sense. Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006', (external link) (Dutch)

- ↑ According to a 1990 study by Statistics Netherlands there were 472,600 Dutch Indonesians residing in the Netherlands. They are the descendants of both Dutchmen and native peoples of Indonesia.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Nicholaas, Han; Sprangers, Arno. "Dutch-born 2001, Figure 3 in DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens" (PDF). Nidi.knaw.nl.

- ↑ Based on adding together Afrikaner and Coloured populations.

- ↑ "210,000 emigrants since World War II, after return migration there were 120,000 Netherlands-born residents in Canada in 2001. DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens" (PDF). Nidi.knaw.nl.

- ↑ "210,000 emigrants since World War II, after return migration there were 120,000 Netherlands-born residents in Canada in 2001. DEMOS, 21, 4. Nederlanders over de grens" (PDF). Nidi.knaw.nl.

- ↑ Federal Statistics Office - Foreign population

- ↑ "ABS Ancestry". 2012.

- ↑ Number of people with the Dutch nationality in Belgium as reported by Statistic Netherlands (Dutch)

- ↑ "New Zealand government website on Dutch-Australians". Teara.govt.nz. 2009-03-04. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Joshua Project. "Dutch Ethnic People in all Countries". Joshua Project. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ↑ http://www.bfs.admin.ch/bfs/portal/de/index/themen/01/22/publ.Document.88215.pdf

- ↑ "CBS - One in eleven old age pensioners live abroad - Web magazine". Cbs.nl. 2007-02-20. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ↑ "Table 5 Persons with immigrant background by immigration category, country background and sex. 1 January 2009". Ssb.no. 2009-01-01. Retrieved 2012-08-07.

- ↑ Netherlanders in America, an example of usage of the term Netherlanders, in the title of a 20th century book.

- ↑ Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006, (external link) This includes the Frisians as well.

- ↑ Based on Statistics Canada, Canada 2001 Census.Link to Canadian statistics.

- ↑ "2001CPAncestryDetailed (Final)" (PDF). Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Based on figures given by Professor JA Heese in his book Die Herkoms van die Afrikaner (The Origins of Afrikaners), who claims the modern Afrikaners (who total around 4.5 million) have 35% Dutch heritage. How 'Pure' was the Average Afrikaner?

- ↑ According to Factfinder.census.gov

- ↑ "CBS statline Church membership". Statline.cbs.nl. 2009-12-15. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Religion in the Netherlands. (Dutch)

- ↑ Winkler Prins Geschiedenis der Nederlanden I (1977), p. 150; I.H. Gosses, Handboek tot de staatkundige geschiedenis der Nederlanden I (1974 [1959]), 84 ff.

- ↑ The actual independence was accepted by in the 1648 treaty of Munster, in practice the Dutch Republic had been independent since the last decade of the 16th century.

- ↑ D.J. Noordam, "Demografische ontwikkelingen in West-Europa van de vijftiende tot het einde van de achttiende eeuw", in H.A. Diederiks e.a., Van agrarische samenleving naar verzorgingsstaat (Leiden 1993), 35-64, esp. 40

- ↑ Britannica: "They were divided into three groups: the Salians, the Ripuarians, and the Chatti, or Hessians."(Link)

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;The Franks, who had settled in Toxandria, in Brabant, were given the job of defending the border areas, which they did until the mid-5th century

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'Dutch language' 10 May. 2009; "It derives from Low Franconian, the speech of the Western Franks, which was restructured through contact with speakers of North Sea Germanic along the coast."

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'West Germanic languages'. 10 May. 2009;restructured Frankish—i.e., Dutch;

- ↑ W. Pijnenburg, A. Quak, T. Schoonheim & D. Wortel, Oudnederlands Woordenboek.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009; The administrative organization of the Low Countries (...) was basically the same as that of the rest of the Frankish empire.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;During the 6th century, Salian Franks had settled in the region between the Loire River in present-day France and the Coal Forest in the south of present-day Belgium. From the late 6th century, Ripuarian Franks pushed from the Rhineland westward to the Schelde. Their immigration strengthened the Germanic faction in that region, which had been almost completely evacuated by the Gallo-Romans.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'Fleming and Walloon'. 12 May. 2009;The northern Franks retained their Germanic language (which became modern Dutch), whereas the Franks moving south rapidly adopted the language of the culturally dominant Romanized Gauls, the language that would become French. The language frontier between northern Flemings and southern Walloons has remained virtually unchanged ever since.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;Thus, the town in the Low Countries became a communitas (sometimes called corporatio or universitas)—a community that was legally a corporate body, could enter into alliances and ratify them with its own seal, could sometimes even make commercial or military contracts with other towns, and could negotiate directly with the prince.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;The development of a town’s autonomy sometimes advanced somewhat spasmodically as a result of violent conflicts with the prince. The citizens then united, forming conjurationes (sometimes called communes)—fighting groups bound together by an oath—as happened during a Flemish crisis in 1127–28 in Ghent and Brugge and in Utrecht in 1159.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;All the towns formed a new, non-feudal element in the existing social structure, and from the beginning merchants played an important role. The merchants often formed guilds, organizations that grew out of merchant groups and banded together for mutual protection while traveling during this violent period, when attacks on merchant caravans were common.

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica Online; entry 'History of the Low Countries'. 10 May. 2009;The achievements of the Flemish partisans inspired their colleagues in Brabant and Liège to revolt and raise similar demands; Flemish military incursions provoked the same reaction in Dordrecht and Utrecht

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands entry "Diets". (Dutch)

- ↑ J. Huizinga (1960: 62). Books.google.nl. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Also note that the document itself clearly distinguishes between the Dutch speaking and French speaking parts of the Seventeen provinces. (Link to 1477 document)

- ↑ Cf. G. Parker, The Dutch Revolt (1985), 33-36, and Knippenberg & De Pater, De eenwording van Nederland (1988), 17 ff.

- ↑ Source, the aforementioned 3rd chapter (p3), together with the initial paragraphs of chapter 4, on the establishment of the Dutch Republic.

- ↑ Figures based on a publication by the Netherlands National Institute for Public Health and the Environment (link).

- ↑ Shetter (2002), 201

- ↑ J. Knipscheer and R. Kleber, Psychologie en de multiculturele samenleving (Amsterdam 2005), 76 ff.

- ↑ cf. Pan-Germanism, Pan-Slavism and many other Greater state movements of the day.

- ↑ Het nationaal-socialistische beeld van de geschiedenis der Nederlanden by I. Schöffer. Amsterdam University Press. 2006. Page 92.

- ↑ For example he gave explicit orders not to create a voluntary Greater Dutch Waffen SS division composed of soldiers from the Netherlands and Flanders. (Link to documents)

- ↑ In the 1950s (the peak of traditional emigration) about 350,000 people left the Netherlands, mainly to Australia, New Zealand, Canada, the United States and South Africa. About one-fifth returned. The maximum Dutch-born emigrant stock for the 1950s is about 300,000 (some have died since). The maximum emigrant stock (Dutch-born) for the period after 1960 is 1.6 million. Discounting pre-1950 emigrants (who would be about 85 or older), at most around 2 million people born in the Netherlands are now living outside the country. Combined with the 13,1 million ethnically Dutch inhabitants of the Netherlands, there are about 16 million people who are Dutch, in a minimally accepted sense. Autochtone population at 1 January 2006, Central Statistics Bureau, Integratiekaart 2006', (external link) (Dutch)

- ↑ "Maltho thi afrio lito" is the oldest attested (Old) Dutch sentence, found in the Salic Law, a legal text written around 500.(Source; the Old Dutch dictionary) (Dutch)

- ↑ Taaluniversum website on the Dutch dialects and main groupings. (Dutch)

- ↑ Michael Medved's Biography. "No, America's never been a multicultural society". Townhall.com. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ 2006 New Zealand Census.

- ↑ As many as 100,000 New Zealanders are estimated to have Dutch blood in their veins (some 2% of the current population of New Zealand).

- ↑ Until World War II, Nederlander was used synonym with Diets. However the similarity to Deutsch resulted in its disuse when the German occupiers and Dutch fascists extensively used that name to stress the Dutch as an ancient Germanic people. (Source; Etymologisch Woordenboek) (Dutch)

- ↑ www.etymonline.com (English) and Etymologisch Woordenboek van het Nederlands (Dutch) entries "Dutch" and "Diets".

- ↑ See J. Verdam, Middelnederlandsch handwoordenboek (The Hague 1932 (reprinted 1994)): "Nederlant, znw. o. I) Laag of aan zee gelegen land. 2) het land aan den Nederrijn; Nedersaksen, -duitschland." (Dutch)

- ↑ Author M. Vanhalme on the use of 'Low Countries'. (De Nederlanden) (Dutch)

- ↑ neder- corresponds with the English nether-, which means "low" or "down". See Online etymological dictionary. Entry: Nether.

- ↑ See the history section of the Vanderbilt family article, or visit this link.

- ↑ "It is a common mistake of Americans, or anglophones in general, to think that the 'van' in front of a Dutch name signifies nobility." (Source.); "Von may be observed in German names denoting nobility while the van, van der, van de and van den (whether written separately or joined, capitalized or not) stamp the bearer as Dutch and merely mean 'at', 'at the', 'of', 'from' and 'from the' (Source: Genealogy.com), (Institute for Dutch surnames, in Dutch)

- ↑ Most common names of occupational origin. Source 1947 Dutch census. (Dutch)

- ↑ The Anglo-Saxon Church - Catholic Encyclopedia article

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 The Dutch Republic Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806, ISBN 0-19-820734-4

- ↑ A 2004 study conducted by Statistics Netherlands shows that 50% of the population claim to belong to a Christian denomination, 9% to other denominations and 42% to none. In the same study, 19% of the people claim go to church at least once a month, another 9% less than once a month, and 72% hardly ever or never. Statistical Yearbook of the Netherlands 2006, page 43

- ↑ Religion in the Netherlands, by Statistics Netherlands. (Dutch)

- ↑ A.M. van der Woude, Nederland over de schouder gekeken (Utrecht 1986), 11-12. (Dutch)

- ↑ Dutch Culture in a European Perspective; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ↑ 71.0 71.1 Voor wie Nederland en Vlaanderen wil leren kennen. By J. Wilmots

- ↑ Frisia. 'Facts and fiction' (1970), by D. Tamminga. (Dutch)

- ↑ Cf. Geoffrey Parker, The Dutch Revolt: "Gradually a consistent attitude emerged, a sort of 'collective identity' which was distinct and able to resist the inroads, intellectual as well as military, of both the Northern Dutch (especially during the crisis of 1632) and the French. This embryonic 'national identity' was an impressive monument to the government of the archdukes, and it survived almost forty years of grueling warfare (1621-59) and the invasions of Louis XIV until, in 1700, the Spanish Habsburgs died out." (Penguin edition 1985, p. 260). See also J. Israel, The Dutch Republic, 1477-1806, 461-463 (Dutch language version).

- ↑ Fred M. Shelley, Nation Shapes: The Story Behind the World's Borders, 2013, page 97

- ↑ National minorities in Europe, W. Braumüller, 2003, page 20.

- ↑ Nederlandse en Vlaamse identiteit, Civis Mundi 2006 by S.W Couwenberg. ISBN 90-5573-688-0. Page 62. Quote: "Er valt heel wat te lachen om de wederwaardigheden van Vlamingen in Nederland en Nederlanders in Vlaanderen. Ze relativeren de verschillen en beklemtonen ze tegelijkertijd. Die verschillen zijn er onmiskenbaar: in taal, klank, kleur, stijl, gedrag, in politiek, maatschappelijke organisatie, maar het zijn stuk voor stuk varianten binnen één taal-en cultuurgemeenschap." The opposite opinion is stated by L. Beheydt (2002): "Al bij al lijkt een grondiger analyse van de taalsituatie en de taalattitude in Nederland en Vlaanderen weinig aanwijzingen te bieden voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit. Dat er ook op andere gebieden weinig aanleiding is voor een gezamenlijke culturele identiteit is al door Geert Hofstede geconstateerd in zijn vermaarde boek Allemaal andersdenkenden (1991)." L. Beheydt, "Delen Vlaanderen en Nederland een culturele identiteit?", in P. Gillaerts, H. van Belle, L. Ravier (eds.), Vlaamse identiteit: mythe én werkelijkheid (Leuven 2002), 22-40, esp. 38. (Dutch)

- ↑ Dutch Culture in a European Perspective: Accounting for the past, 1650-2000; by D. Fokkema, 2004, Assen.

- ↑ Geschiedenis van de Nederlanden, by J.C.H Blom and E. Lamberts, ISBN 978-90-5574-475-6; page 383. (Dutch)

- ↑ Languages in contact and conflict ... - Google Books. Books.google.com. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Taschenatlas Weltgeschichte, part 1, by H. Kinder and W. Hilgemann. ISBN 978-90-5574-565-4, page 171. (German)

- ↑ "Boise State University thesis by E.L. Knox on the German Eastward Expansion ('Ostsiedlung')". Oit.boisestate.edu. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Voortrekkers van Oud-Nederland; from Nederlands Geschiedenis buiten de grenzen" by J. Dekker (Dutch)

- ↑ Dutch and Flemish Colonization in Mediaeval Germany, by James Westfall Thompson

- ↑ "Article on Dutch settlers in Poland published by the Polish Genealogical Society of America and written by Z. Pentek". Pgsa.org. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ Article published by the Mercator Research center on Dutch settlers in Siberia

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Thomas McGhee, Charles C.; N/A, N/A, eds. (1989). The plot against South Africa (2nd ed.). Pretoria: Varama Publishers. ISBN 0-620-14537-4.

- ↑ 87.0 87.1 Fryxell, Cole. To Be Born a Nation. pp. 9–327.

- ↑ 88.0 88.1 88.2 88.3 88.4 88.5 Kaplan, Irving. Area Handbook for the Republic of South Africa. p. 42-591.

- ↑ Nelson, Harold. Zimbabwe: A Country Study. pp. 237–317.

- ↑ Roskin, Roskin. Countries and concepts: an introduction to comparative politics. pp. 343–373.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 Dowden, Richard (2010). Africa: Altered States, Ordinary Miracles. Portobello Books. pp. 380–415. ISBN 978-1-58648-753-9.

- ↑ "Is Afrikaans Dutch?". DutchToday.com. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ↑ "Afrikaans language - Britannica Online Encyclopedia". Britannica.com. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ↑ "The Afrikaans Language | about | language". Kwintessential.co.uk. Retrieved 2012-09-10.

- ↑ http://portal.unesco.org/ci/en/files/22635/11546101681netherlands_voc_archives.doc/netherlands%2Bvoc%2Barchives.doc

- ↑ "Easternization of the West: Children of the VOC". Dutchmalaysia.net. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

- ↑ (Dutch) Willems, Wim, ’De uittocht uit Indie 1945-1995’ (Uitgeverij Bert Bakker, Amsterdam, 2001) ISBN 90-351-2361-1

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 Nederland-Australie 1606-2006 on Dutch emigration.

- ↑ The U.S. declared its independence in 1776; the first Dutch settlement was built in 1614: Fort Nassau, where presently Albany, New York is positioned.

- ↑ "How the Dutch became Americans, American Civil War. (includes reference on fighting for the North)". Library.thinkquest.org. Retrieved 2010-08-27.

Further reading

- Blom, J. C. H. and E. Lamberts, eds. History of the Low Countries (2006) 504pp excerpt and text search; also complete edition online

- Bolt, Rodney.The Xenophobe's Guide to the Dutch. Oval Projects Ltd 1999, ISBN 1-902825-25-X

- Boxer. Charles R. The Dutch in Brazil, 1624-1654. By The Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1957, ISBN 0-208-01338-5

- Burke, Gerald L. The making of Dutch towns: A study in urban development from the 10th-17th centuries (1960)

- De Jong, Gerald Francis. The Dutch in America, 1609–1974.Twayne Publishers 1975, ISBN 0-8057-3214-4

- Hunt, John. Dutch South Africa: early settlers at the Cape, 1652–1708. By John Hunt, Heather-Ann Campbell. Troubador Publishing Ltd 2005, ISBN 1-904744-95-8.

- Koopmans, Joop W., and Arend H. Huussen, Jr. Historical Dictionary of the Netherlands (2nd ed. 2007)excerpt and text search

- Kossmann-Putto, J. A. and E. H. Kossmann. The Low Countries: History of the Northern and Southern Netherlands (1987)

- Kroes, Rob. The Persistence of Ethnicity: Dutch Calvinist pioneers. By University of Illinois Press 1992, ISBN 0-252-01931-8

- Stallaerts, Robert. The A to Z of Belgium (2010), a historical encyclopedia

- White & Boucke. The UnDutchables. ISBN 978-1-888580-44-0.

Other languages

- Voor wie Nederland en Vlaanderen wil leren kennen. By J. Wilmots and J. De Rooij, 1978, Hasselt/Diepenbeek. (Dutch)

- Handgeschreven wereld. Nederlandse literatuur en cultuur in de middeleeuwen. By D. Hogenelst and Frits van Oostrom, 1995, Amsterdam. (Dutch)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Notable Dutch people over the ages. |

| Wikiquote has a collection of quotations related to: Dutch proverbs |

| ||||||||||||||||||||