Dunkleosteus

| Dunkleosteus Temporal range: Late Devonian, 380–360Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Reconstructed skull, Queensland Museum | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | †Placodermi |

| Order: | †Arthrodira |

| Family: | †Dunkleosteidae |

| Genus: | †Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956 |

| Type species | |

| Dinichthys terrelli Newberry, 1873 | |

| Species | |

|

D. terrelli (Newberry, 1873 [originally Dinichthys]) | |

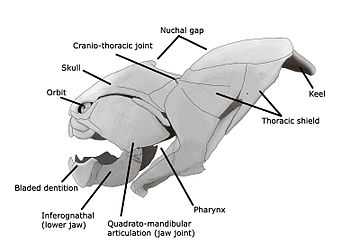

Dunkleosteus (from "[David] Dunkle" + osteus [οστεος, Greek: bone]) is a genus of prehistoric fish existing during the Late Devonian period, about 380–360 million years ago. Some of the species, such as D. terrelli, D. marsaisi, and D. magnificus, are among the largest arthrodire placoderms ever to have lived.

The largest species, D. terrelli, measuring up to 10 metres (33 ft)[1][2] and weighing 3.6 tonnes (4.0 short tons),[3] was a hypercarnivorous apex predator. Few other placoderms, save, perhaps, its contemporary, Titanichthys, rivaled Dunkleosteus in size.

Dunkleosteus is a pachyosteomorph arthrodire originally placed in the family Dinichthyidae, a family composed mostly of large, carnivorous arthrodires like Gorgonichthys. Anderson (2009) suggests that because of its primitive jaw structure Dunkleosteus should be placed outside the family Dinichthyidae, perhaps close to the base of the clade Pachyosteomorpha, near Eastmanosteus. Carr and Hlavin (2010) resurrect Dunkleosteidae and place Dunkleosteus, Eastmanosteus and a few other genera from Dinichthyidae within it[4] (Dinichthyidae, in turn, is made into a monospecific family[5]).

New studies have revealed several features in both its food and biomechanics as well as its ecology and physiology. Placodermi first appeared in the Silurian, and the group became extinct during the transition from the Devonian to the Carboniferous, leaving no descendants. The class lasted barely 50 million years, in comparison to the 400 million year long history of sharks.[6]

In recent decades, Dunkleosteus has achieved recognition in popular culture, with a large number of specimens on display, and notable appearances in entertainment media. Numerous fossils of some species have been found in North America, Poland, Belgium and Morocco.

Description

Due to its heavily armoured nature, Dunkleosteus was probably a relatively slow but powerful swimmer. It is thought to have dwelt in diverse zones of inshore waters. Fossilization tends to have preserved only the especially armoured frontal sections of specimens, and thus it is uncertain what exactly the hind sections of this ancient fish were like. As such, the reconstructions of the hindquarters are often based on smaller arthrodires, such as Coccosteus, that had hind sections preserved.

The most famous specimens of Dunkleosteus are displayed at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. Others are displayed at the American Museum of Natural History and in the Queensland Museum in Brisbane, Queensland.

Instead of teeth, Dunkleosteus possessed two pairs of sharp bony plates which formed a beak-like structure.

Different bite forces are provided by different reports. After studying a biomechanical model of the fish's jaws, scientists at the Field Museum of Natural History and the University of Chicago concluded that Dunkleosteus had the second most powerful bite of any fish (megalodon being the strongest). Dunkleosteus could create a pressure of 1,100 pounds per square inch (7.6 MPa) and up to 1,800 pounds per square inch (12 MPa)[7] at the tip of one of its fangs, placing Dunkleosteus in the same league as Tyrannosaurus rex and modern crocodiles as having one of the most powerful known bite forces.[8] However, in 2008, a team of scientists led by S. Wroe conducted an experiment to determine the bite force of the great white shark, using a 2.4 metres (8 ft) long specimen, and then isometrically scaling the results for its maximum confirmed size and the conservative minimum and maximum body mass of Megalodon, placing the bite force of the latter between 108,514 N (24,400 lbf) and 182,201 N (41,000 lbf) in a posterior bite. Compared to 18,216 N (4,100 lbf) for the largest confirmed great white shark,[9] and 5,300 N (1,200 lbf) for Dunkleosteus.[10]

Dunkleosteus could open its mouth in one-fiftieth of a second, which would have caused a powerful suction that pulled the prey into its mouth,[8] a food-capture technique used by many fish today.

The discovery of Dunkleosteus armor with unhealed bite marks strongly suggest that they cannibalized each other when the opportunity arose. Frequently, fossils of Dunkleosteus are found with boluses of fish bones, semi-digested and partially eaten remains of other fish.[6] As a result, the fossil record indicates that it may have routinely regurgitated prey bones rather than digest them.

Dunkleosteus, together with most other placoderms, may have also been among the first vertebrates to internalize egg fertilization, as seen in some modern sharks.

Morphological studies done on the "jaw bones" (inferognathals) of juvenile and adult Dunkleosteus suggest that Dunkleosteus went through a change in jaw morphology and diet as it aged. Juveniles had stiffer jaws more similar to Coccosteus, and appear to have fed on various soft-bodied aquatic animals. The jaws of adults were more flexible to hold struggling prey, and were well equipped to bite through the bony armor of hard-bodied animals such as other placoderms.

Species

There have been at least ten different species[4][11] of Dunkleosteus described so far.

The type species D. terrelli is the largest, best known species of the genus. It has a rounded snout. D. terrelli's fossil remains are found in Upper Frasnian to Upper Famennian Late Devonian strata of the United States (Huron and Cleveland Shales of Ohio, the Conneaut of Pennsylvania, Chattanooga Shale of Tennessee, Lost Burro Formation, California, and possibly Ives breccia of Texas[11]) and Europe.

D. ? belgicus is known from fragments described from the Famennian of Belgium. The median dorsal plate is characteristic of the genus, but, a plate that was described as a suborbital is apparently an anterior-lateral plate.[11]

D. denisoni is known from a small median dorsal plate, typical in appearance for Dunkleosteus, but much smaller than normal.[11]

D. marsaisi refers to the Dunkleosteus fossils from the Lower Famennian Late Devonian strata of the Atlas Mountains in Morocco. It differs in size, the known skulls averaging a length of 35 centimetres and in form to D. terrelli. In D. marsaisi, the snout is narrower, and there may be a postpineal fenestra present. Many researchers and authorities consider it a synonym of D. terrelli.[12] H. Schultze regards D. marsaisi as a member of Eastmanosteus.[11][13]

D. magnificus is a large placoderm from the Frasnian Rhinestreet shale of New York. It was originally described as "Dinichthys magnificus" by Hussakof and Bryant in 1919, then as "Dinichthys mirabilis" by Heintz in 1932. Dunkle and Lane moved it to Dunkleosteus in 1971.[11]

D. missouriensis is known from fragments from Frasnian Missouri. Dunkle and Lane regard them as being very similar to D. terrelli.[11]

D. newberryi is known primarily from a 28 centimetre long infragnathal that has a prominent anterior cusp. Found in the Frasnian portion of the Genesee group of New York, and originally described as "Dinichthys newberryi".[11]

D. amblyodoratus is known from some fragmentary remains from Late Devonian strata of Kettle Point, Canada. The species name means "blunt spear," and refers to the way the nuchal and paranuchal plates in the back of the head form the shape of a blunted spearhead. Although it is known only from fragments, it is estimated to have been about 20 feet long in life.[4]

D. raveri is a small, possibly 1-metre-long species known from an uncrushed skull roof, found in a carbonate concretion from near the bottom of the Huron Shale, of the Famennian Ohio Shale strata. Besides its small size, it had comparatively large eyes. Because D. raveri was found in the strata directly below the strata where the remains of D. terrelli are found, it is suggested that D. raveri may have given rise to D. terrelli. The species name commemorates Clarence Raver of Wakeman, Ohio, U.S., who discovered the concretion the holotype was found in.[4]

History

Dunkleosteus was named in 1956 to honour David Dunkle, then curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the Cleveland Museum of Natural History. The type species (D. terreli) was originally described in 1873 as a species of Dinichthys.

See also

- List of placoderms

References

- ↑ Ancient Fish With Killer Bite. Science News. May 19, 2009.

- ↑ Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London: Marshall Editions. p. 33. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- ↑ Monster fish crushed opposition with strongest bite ever. The Sydney Morning Herald. November 30, 2006.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 Carr R. K., Hlavin V. J. (2010). "Two new species of Dunkleosteus Lehman, 1956, from the Ohio Shale Formation (USA, Famennian) and the Kettle Point Formation (Canada, Upper Devonian), and a cladistic analysis of the Eubrachythoraci (Placodermi, Arthrodira)". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 159 (1): 195–222. doi:10.1111/j.1096-3642.2009.00578.x.

- ↑ Carr, Robert K.; William J. Hlavin (September 2, 1995). "Dinichthyidae (Placodermi):A paleontological fiction?". Geobios 28: 85–87. doi:10.1016/S0016-6995(95)80092-1.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 "Dunkleosteus Placodermi Devonian Armored Fish from Morocco". Fossil Archives. The Virtual Fossil Museum. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ "Ancient predator had strongest bite of any fish, rivaling bite of large alligators and T. rex". http://phys.org. Retrieved November 28, 2006.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Roy Britt, Robert (28 November 2006). "Prehistoric Fish Had Most Powerful Jaws". LiveScience. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- ↑ Wroe, S.; Huber, D. R. ; Lowry, M. ; McHenry, C. ; Moreno, K. ; Clausen, P. ; Ferrara, T. L. ; Cunningham, E. ; Dean, M. N. ; Summers, A. P. (2008). "Three-dimensional computer analysis of white shark jaw mechanics: how hard can a great white bite?". Journal of Zoology 276 (4): 336–342. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2008.00494.x.

- ↑ Anderson, Philip; Westneat, Mark (February 2007). "Feeding mechanics and bite force modelling of the skull of Dunkleosteus terrelli, an ancient apex predator". Royal Society 3 (1): 77–80. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2006.0569.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Denison, Robert (1978). Placodermi Volume 2 of Handbook of Paleoichthyology'. Stuttgart New York: Gustav Fischer Verlag. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-89574-027-4.

- ↑ Murray, A.M. (2000). "The Palaeozoic, Mesozoic and Early Cenozoic fishes of Africa". Fish and Fisheries 1 (2): 111–145. doi:10.1046/j.1467-2979.2000.00015.x.

- ↑ Schultz, H (1973). "Large Upper Devonian arthrodires from Iran". Fieldiana Geology 23: 53–78.

- Shape variation between arthrodire morphotypes indicates possible feeding niches by Philip S. L. Anderson, Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology volume 28, #4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dunkleosteus. |

- Introduction to the Placodermi: Extinct Armored Fishes with Jaws. Waggoner, Ben (2000). Retrieved Aug 1, 2005

- MSNBC: Prehistoric fish packed a mean bite

- BBC: Ancient 'Jaws' had monster bite

- Dunkleosteus on Prehistoric Wildlife, with size comparison

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||