Duncan Curry

| Duncan Fraser Curry | |

|---|---|

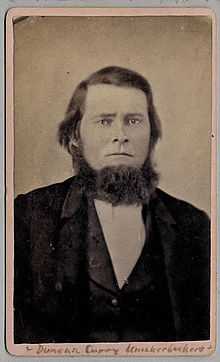

Early photograph of Curry | |

| Born |

Duncan Fraser Curry November 28, 1812 New York City, New York |

| Died |

April 0, 1894 (aged 81) Brooklyn, New York |

| Known for | first president of the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club, 1845 |

Duncan Fraser Curry (November 28, 1812 – April 1894) was an American baseball pioneer and insurance executive.

Curry was the first president of the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club, reported to be the first organized baseball club in 1845. He is also credited with participating in the drafting of the Knickerbocker Rules, the first written set of official baseball rules. He also served on the game's various rules committees from 1845 until at least 1856.

Curry was also one of the founders of the Republic Fire Insurance Company and served as its secretary from 1852 to 1882.

Biography

Curry was born in New York City in November 28, 1812.[1]

Curry worked in the insurance business for more than 35 years. From 1843 to 1852, he was the Secretary of the City Fire Insurance Company. In 1852, he was one of the founding officers of the Republic Fire Insurance Company, known as "The Pioneer Mutual Fire Insurance Co. Combining the Economy of the Mutual Plan with the Security of a Cash Capital."[2] He served as the Secretary of Republic Fire Insurance Company for 30 years from its formation in 1852 until 1882.[1][3][4]

In 1844, Duncan Curry was one of nine "sporting gentlemen" who, along with George L. Schuyler and Hamilton Wilkes formed the New York Yacht Club.

Knickerbockers Base Ball Club

Participation in early informal games

In 1842, Curry was part of a group of prominent New York businessmen who gathered in the afternoons to play a game that became baseball. Curry later recalled: "For several years it had been our habit to casually assemble on a plot of ground that is now known as Twenty-seventh street and Fourth avenue, where the Harlem Railroad Depot afterward stood. We would take our bats and balls with us and play any sort of game. We had no name in particular for it. Sometimes we batted the ball to one another or sometimes we played one o'cat."[5]

Baseball pioneer and Hall of Fame inductee John Montgomery Ward interviewed several of the early members of the group, including Curry, and later wrote the following about the early development of the game in New York: "When in about the year 1842 or earlier, Dr. D. L. Adams, Alexander J. Cartwright, Colonel James Lee, Duncan F. Curry, E. R. Dupignac, William F. Ladd and other prominent business and professional men of New York City, seeking some medium for outdoor exercise, turned to the boy's game of Base Ball, there was not a code of rules nor any written records of the game."[6] In his history of baseball, Al Spalding wrote of the group: "Nevertheless, it is of record that as early as the year 1842, a number of New York gentlemen -- and I used the term 'gentlemen' in its highest social significance -- were accustomed to meet regularly for Base Ball practice games. It does not appear that any of these were world-beaters in the realm of athletic sports."[7]

Formation of the Knickerbockers

In the spring of 1845, one of the members of the group, Alexander Cartwright, proposed that they establish a formal baseball club. A committee consisting of Cartwright, Curry, William Wheaton, William H. Tucker and Dupignac was charged with responsibility to secure signatures of players wishing to belong to the club and to otherwise organize the club.[8][9] On September 23, 1845, at a meeting held at McCarty's Hotel in New York City (located at Hudson and 12 Streets), the Knickerbockers Base Ball Club was formally established, and Curry was selected as its first president. The Knickerbockers were reported to have been the first organized baseball club.[1][10] In his history of the sport, Al Spalding cited the formation of the Knickerbockers as a seminal point in baseball history: "The organization of the Knickerbocker Base Ball Club was the beginning of a most important era in the history of the game, for it was the first recorded movement of that kind. The right and title to the distinction of being the first organized Base Ball club in the world belongs to the old Knickerbocker Club. That honor has never been called in question. For more than thirty years the Knickerbocker Club maintained an amateur organization, and as such was regarded as a model in every respect."[11]

Drafting of the Knickerbocker Rules

Curry also served on the committee that drafted the Knickerbocker Rules, reputed to be the first set of official written rules for the game of baseball.[1] Differing accounts as to who deserved credit for the establishment of the Knickerbocker Rules have been posthumously attributed to Curry over the years. On one occasion, he was reported to have stated that he and William Tucker had crafted the rules.[12] In the recounting of an interview with reporter Will Rankin, Curry was quoted as rejecting the notion that Henry Chadwick should be credited. According to Rankin, Curry said: "Thomas Fiddlesticks [Chadwick] had no more to do with the original rules than you had. William Wheaton, William H. Tucker and I drew up the first set of rules and the game was developed by the people who played it and were connected with it."[13] However, in a 1911 book published by Alfred Henry Spink, Curry was quoted as giving principal credit for creation of the new game to Alexander Cartwright. Spink's book attributed the following to Curry:

"Well do I remember the afternoon that Alex Cartwright came up to the ball field with a new scheme for playing ball. . . . On this afternoon I have already mentioned, Cartwright came to the field – the march of improvement had driven us further north and we located on a piece of property on the slope of Murray Hill, between the railroad cut and Third avenue – with his plans drawn up on paper. He had arranged for two nines, the ins and outs.

"That is, while one set of players were taking their turn at bat the other side was placed in their respective positions on the field. He had laid out a diamond-shaped field, with canvas bags filled with sand or sawdust for bases at three points and an iron plate for the home base. He had arranged for a catcher, a pitcher, three basemen, a short fielder and three outfielders. His plan met with much good derision, but he was so persistent in having us try his new game that we finally consented more to humor him than with any thought of it becoming a reality. . . When we saw what a great game Cartwright had given us, and as his suggestion for forming a club to play it met with our approval, we set about to organize a club."[5]

Organization of the first baseball game

"An awful beating you could say at our own game, but, you see, the majority of the New York Club's players were cricketers, and clever ones at that game, and their batting was the feature of their work. The chief trouble was that we had held our opponents too cheaply and few of us had practiced any prior to the contest, thinking that we knew more about the game than they did. . . . The pitcher of the New York nine was a cricket bowler of some note, and while one could use only the straight arm delivery he could pitch an awfully speedy ball. The game was in a crude state. No balls were called on the pitcher and that was a great advantage to him, and when he did get them over the plate they came in so fast our batsmen could not see them."[20]

Committee on Rules

Curry continued to be a prominent member of the Knickerbockers for many years.[21][22] He was also appointed by the Knickerbockers as a member of the game's various rules committees for more than a decade and through at least 1856. An 1848 pamphlet published by the Knickerbockers identifies Curry, Alexander Cartwright, Doc Adams, Eugene Plunkett, and J. P. Mumford as the members of the committee "to revise constitution and By-Laws."[23]

In November 1853, Curry was assigned to a rules committee that included Doc Adams, William H. Tucker, and members of another New York baseball club, the Eagle Club.[22][24] The committee met on April 1, 1854 at Smith's on Howard Street in New York. The committee adopted a set of rules that would govern play among the three leading clubs, the Knickerbockers, the Gotham Club, and the Eagle Club. Among other things, the 1854 rules included specifications for the size and weight of the ball, set the dimensions of the infield, and adopted the "force out rule" of tagging first base to put a batter out on a ground ball.[24]

In 1856, Curry became involved in a debate among the Knickerbockers as to whether to allow nonmembers to participate in games if fewer than 18 men were available to play. Curry, as the leader of the group that historian John Thorn has dubbed the "Old Fogy" or "exclusionary clique," resisted the proposal and offered a counter-proposal that no non-members should be allowed to participate as long as at least 14 members were available. The Curry measure was approved by a vote of 13 to 11. At that time, the club also debated a new rule to replace the prior practice of playing until a team scored 21 runs. The debate focused on whether the game should consist of seven or nine innings. Curry was an advocate of the seven-inning format and was appointed to a committee to consider the question.[25] Although the majority of the Knickerbockers sided with Curry on the seven-inning format, Louis F. Wadsworth (who favored the nine-inning format) called for a convention among the baseball clubs to agree on a format. The convention (known as the first National Association meetings) was held in 1857, at which time the delegates approved the nine-inning format. In his history of early baseball, John Thorn wrote that the adoption of Wadsworth's nine-inning format marked the end of power for the Knickerbockers' "Old Fogy" clique.[26]

Claim as "Father of Baseball"

In 1905, Al Spalding wrote in his Spalding's Official Base Ball Guide that "the original Knickerbocker Club should be honored and remembered as the founders of our national game." In particular, he cited 11 original Knickerbockers as deserving of the honor, including Curry, Doc Adams, Alexander Cartwright, E. R. Dupignac, William Wheaton and William H. Tucker.[27]

In March 1894, a controversy developed when James Whyte Davis, who had been president of the Knickerbockers from 1858 to 1860, announced plans to request ten cent subscriptions from baseball players so that, upon his death, a tombstone could be erected identifying him as the "Father of Baseball." Davis's request drew an angry letter from an anonymous baseball person that was published in The Sporting Life. The letter included the following comments about Curry:"Mr. Curry was one of the organizers of the Knickerbocker Club and was elected the first president of that organization in 1845 at the club's first meeting. He was on the Committee on Rules and helped draft the first rules under which base ball was regularly played. So if any one deserves the title of 'Father of Base Ball,' Mr. Curry does and not Mr. Davis."[28]

Curry died one month after the controversy. He was buried at Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery with a white marble monument identifying him as the "Father of Baseball."[29] In his 2003 book "Baseball Legends of Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery," baseball historian Peter Nash wrote that Green-Wood is the common resting place of four men vying for the "Father of Baseball" title—Curry, Henry Chadwick, William Wheaton, and William Tucker.[30][31] Nash opined that "a case can be made that "Curry, Wheaton, Tucker, and Cartwright were the true founding fathers of the modern game."[32]

Role in Mills Commission findings

Curry also played a posthumous role in the conclusion of the Mills Commission crediting Abner Doubleday with inventing the game of baseball. In an 1877 interview with reporter Will Rankin, Curry reportedly said that a Mr. Wadsworth had in 1845 brought a diagram to the field where the Knickerbockers played showing the baseball diamond laid out substantially in its current form. According to Curry, the diagram led to much discussion, and the club agreed to try it. In a decision that has been hotly debated for over 100 years, the Mills Commission concluded in 1905 that the diagram could be traced to Doubleday and cited it as evidence of Doubleday's role in the origin of the game.[33]

Family and later years

At the time of the 1850 United States Census, Curry was living in New York City's 16th Ward, and his occupation was listed as a clerk. Other members of his household were his grandmother Flora Fraser (age 90),[34] Elizabeth Robinson (age 53), Margaret Blount (age 47), Mary Ann Blount (age 21), David Blount (age 15), George Blount (age 13), Duncan F. Blount (age 10), and servant Amenia Hafe (age 18).[35]

On August 16, 1859, Curry was married at the Church of the Transfiguration in New York to Angie Kerr, the youngest daughter of William R. Kerr of Cincinnati, Ohio.[36]

At the time of the 1860 United States Census, Curry was living in New York City's 22nd Ward, and his occupation was listed as a bookkeeper. He was shown in the Census as having real estate valued at $8,000 and personal estate valued at $1,000. Other members of his household were Elizabeth Robinson (age 64), Angie Curry (age 30), Mary G. Curry (age 6 months), and two domestics Mary Kenn and Catherine Bolen.[37]

Federal tax assessor's records show D. F. Curry of New York as having taxable property of $4,800 in 1864, $5,165 in 1865 and $4,921 in 1866. The 1866 lists shows his address as 153 Broadway.[38][39]

By 1884, Curry had moved to Brooklyn and was residing at 221 Gates Avenue.[40] He later lived in Brooklyn at 282A Gates Avenue and 279 Ryerson.[41][42] Curry died at his home in Brooklyn in April 1894 at age 81.[1] He died due to heart disease.[43][44] His funeral was held at St. James Episcopal Church in Brooklyn. He was survived by a son, Duncan Curry, and a daughter, Mary Gray Curry Wolff.[1]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 1.5 "Duncan Fraser Curry". The New York Times. April 19, 1894.

- ↑ "Certificate issued by Republic Fire Ins. Co.". Library of Congress. c. 1860.

- ↑ "Insurance". The New York Times. June 19, 1852.(listing Curry as Secretary in the year of Republic's formation)

- ↑ "Insurance Affairs: Reported Withdrawal of Several Companies -- The Latest, The Republic". The New York Times. January 22, 1882.(listing Curry as Secretary)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Alfred Henry Spink (1911). The National Game. SIU Press. pp. 54–55.

- ↑ John M. Ward letter to Albert Spaulding, dated June 19, 1907, on the origin of baseball.

- ↑ Albert G. Spaulding. America's National Game. p. 49.

- ↑ Spalding, p. 52.

- ↑ Joel Zoss, John Bowman (2004). Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball. University of Nebraska Press. p. 16. ISBN 0803299206.("Wheaton, Cartwright, Curry, W. H. Tucker, and Dupignac were appointed by their mates to organize the club.")

- ↑ William J. Ryczek (2009). Baseball's First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War. McFarland. p. 43. ISBN 0786441941.

- ↑ Spaulding, p. 55.

- ↑ William J. Ryczek (2009). Baseball's First Inning: A History of the National Pastime Through the Civil War. McFarland. p. 29. ISBN 0786441941.

- ↑ Peter J. Nash (2003). Baseball Legends of Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery. Arcadia Publishing. p. 20. ISBN 0738534781.

- ↑ "Baseball's First Game Recreated". The New York Times. June 18, 1976.(referring to the game as "the first 'officially recorded' game of baseball")

- ↑ "Baseball's First Organized Game In 1846". Sarasota Journal (UPI story). June 18, 1964.("In 1846, the first baseball game between organized teams took place in Hoboken, N.J.")

- ↑ "Hoboken .Marks 150th Anniversary Of First Baseball Game". Rochester Sentinel. June 19, 1996.("Baseball historians tend to side with New Jersey and agree the first game was played June 1846 in Hoboken ...")

- ↑ Ed Shakespeare. When Baseball Returned to Brooklyn. p. 82.("The New York Nine won this first ever baseball game, at Elysian Fields, by a score of 23-1.")

- ↑ Joel Zoss, John Bowman (2004). Diamonds in the Rough: The Untold History of Baseball. p. 289.("Instead, most histories of the game are content to settle on the famous 'only accepted date of baseball's beginning' -- a game played on the Elysian Fields in Hoboken, New Jersey, on June 19, 1846")

- ↑ Maxine N. Lurie, Marc Mappen. Encyclopedia of New Jersey. Rutgers University Press. p. 58.("Baseball as it is played today throughout the world began on June 18, 1846, at the Elysian Fields in Hoboken.")

- ↑ Spink, p. 56.

- ↑ "Handwritten notes of Henry Chadwick, Henry Chadwick personal research file". Robert Edward Auctions. Retrieved June 4, 2012.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Nash 2003, p. 21.

- ↑ Monica Nucciarone, John Thorn (2009). Alexander Cartwright: The Life Behind the Baseball Legend. University of Nebraska Press. p. 162.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Dean A. Sullivan (1997). Early Innings: A Documentary History of Baseball, 1825-1908. Univ. of Nebraska Press. p. 18.

- ↑ Thorn 2012, pp. 51-52.

- ↑ Thorn 2012, p. 53.

- ↑ Nucciarone & Thorn, p. 210.

- ↑ "Mr. Davis Called Down". The Sporting Life. March 31, 1894. p. 4.("Among the enrolled members of the Knickerbocker Club in 1854 - the closing of the 10th season were: Duncan F. Curry (who died in 1894).")

- ↑ Peter J. Nash (2003). Baseball Legends of Brooklyn's Green-Wood Cemetery. Arcadia Publishing. p. 8. ISBN 0738534781.("I stumbled across a weathered white marble monument that literally stopped me in my tracks. It read, 'Duncan Curry, Father of Baseball.'")

- ↑ Nash 2003, p. 22.

- ↑ "Ground as Hallowed as Cooperstown: Green-Wood Cemetery, Home to 200 Baseball Pioneers". The New York Times. April 1, 2004.

- ↑ Nash 2003, p. 20.

- ↑ John Thorn (2012). Baseball in the Garden of Eden: The Secret History of the Early Game. Simon and Schuster. pp. 15–21. ISBN 0743294041.

- ↑ New York, Death Newspaper Extracts, 1801-1890 (Barber Collection) Record identifies Flora Frazer as follows: "Apr. 6 [1851] Flora Vans Faser 91y wid Duncan Fraser gr s D F Curry of 229 W 10 St."

- ↑ Census entry for Duncan F. Curry, age 38. Ancestry.com. 1850 United States Federal Census [database on-line]. Census Place: New York Ward 16 District 2, New York, New York; Roll: M432_553; Page: 187B; Image: 380.

- ↑ "Married". The New York Times. August 19, 1859.

- ↑ Census entry for Duncan F. Curry.

- ↑ Ancestry.com. U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 [database on-line]. National Archives (NARA) microfilm series: M603, M754-M771, M773-M777, M779-M780, M782, M784, M787-M789, M791-M793, M795, M1631, M1775-M1776, T227, T1208-T1209.

- ↑ Ancestry.com. U.S. IRS Tax Assessment Lists, 1862-1918 [database on-line]. National Archives (NARA) microfilm series: M603, M754-M771, M773-M777, M779-M780, M782, M784, M787-M789, M791-M793, M795, M1631, M1775-M1776, T227, T1208-T1209.

- ↑ Brooklyn, New York, City Directory, 1884, p. 166. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 (Beta) [database on-line].

- ↑ Brooklyn, New York, City Directory, 1885, p. 337. Ancestry.com. U.S. City Directories, 1821-1989 (Beta) [database on-line].

- ↑ Ancestry.com. Brooklyn, New York Directories, 1888-1890 [database on-line].

- ↑ "none". The Chronicle. April 26, 1894. p. 210.

- ↑ "Personals". The Weekly Underwriter, vol. 50. p. 286.