Drift velocity

The drift velocity is the average velocity that a particle, such as an electron, attains due to an electric field. It can also be referred to as axial drift velocity since particles defined are assumed to be moving along a plane. In general, an electron will ‘rattle around’ in a conductor at the Fermi velocity randomly. An applied electric field will give this random motion a small net velocity in one direction.

In a semiconductor, the two main carrier scattering mechanisms are ionized impurity scattering and lattice scattering.

Because current is proportional to drift velocity, which is, in turn, proportional to the magnitude of an external electric field, Ohm's law can be explained in terms of drift velocity.

Drift velocity is expressed in the following equations:

where  is the current density,

is the current density,  is charge density (in units C/m3), and

is charge density (in units C/m3), and  is the drift velocity, and where

is the drift velocity, and where  is the electron mobility (in units (m^2)/V*s) and

is the electron mobility (in units (m^2)/V*s) and  is the electric field (in units V/m).

is the electric field (in units V/m).

Mathematical formula

The formula for evaluating the drift velocity of charge carriers in a material of constant cross-sectional area is given by:[1]

where v is the drift velocity of electrons, I is the current flowing through the material, n is the charge-carrier density, A is the area of cross-section of the material and q is the charge on the charge-carrier.

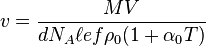

In terms of the basic properties of the right-cylindrical current-carrying metallic conductor, where the charge-carriers are electrons, this expression can be rewritten as [citation needed]:

where,

- v is again the drift velocity of the electrons, in m·s−1;

- M is the molar mass of the metal, in kg·mol−1;

- V is the voltage applied across the conductor, in V;

- NA is Avogadro’s number, in mol−1;

- d is the density (mass per unit volume) of the conductor, in kg·m−3;

- e is the fundamental electric charge, in C;

- ρ0 is the resistivity of the conductor at 0°C, in Ω·m;

- α0 is the temperature coefficent of resistivity of the conductor at 0°C, in K−1;

- T is the temperature of the conductor, in °C,

- ℓ is the length of the conductor, in m; and

- f is the number of free electrons released by each atom.

Numerical example

Electricity is most commonly conducted in a copper wire. Copper has a density of 8.94 g/cm³, and an atomic weight of 63.546 g/mol, so there are 140685.5 mol/m³. In 1 mole of any element there are 6.02×1023 atoms (Avogadro's constant). Therefore in 1m³ of copper there are about 8.5×1028 atoms (6.02×1023 × 140685.5 mol/m³). Copper has one free electron per atom, so n is equal to 8.5×1028 electrons per m³.

Assume a current I = 3 amperes, and a wire of 1 mm diameter (radius in meters = 0.0005m). This wire has a cross sectional area of 7.85×10−7 m2 (A = π×0.00052). The charge of 1 electron is q=−1.6×10−19 Coulombs. The drift velocity therefore can be calculated:

Analysed dimensionally:

[v] = [amperes] / ( [electron/m3] × [m2] × [coulombs/electron] )

- = [coulombs] / ( [seconds] × [electron/m3] × [m2] × [coulombs/electron] )

- = [coulombs] / ( [seconds] × [meters-1] × [coulombs] )

- = [meters] / [second]

Therefore in this wire the electrons are flowing at the rate of −0.00029 m/s, or very nearly −1.0 m/hour.

By comparison, the Fermi velocity of these electrons (which, at room temperature, can be thought of as their approximate velocity in the absence of electric current) is around 1570 km/s.[2]

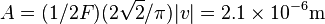

In the case of alternating current, the direction of electron drift switches with the frequency of the current. In the example above, if the current were to alternate with the frequency of F = 60 Hz, drift velocity would likewise vary in a sine-wave pattern, and electrons would fluctuate about their initial positions with the amplitude of:

See also

- Electron mobility

- Speed of electricity

- Drift chamber

- Guiding center

References

- ↑ Griffiths, David (1999). Introduction to Electrodynamics (3 ed.). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice-Hall. p. 289.

- ↑ http://230nsc1.phy-astr.gsu.edu/hbase/electric/ohmmic.html Ohm's Law, Microscopic View, retrieved Feb 14, 2009

External links

- Ohm's Law: Microscopic View at Hyperphysics