Draco mindanensis

| Draco mindanensis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Preserved museum specimen | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Subphylum: | Vertebrata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Order: | Squamata |

| Family: | Agamidae |

| Genus: | Draco |

| Species: | D. mindanensis |

| Binomial name | |

| Draco mindanensis Stejneger, 1908 | |

| Synonyms | |

Draco mindanensis, commonly known as the Mindanao flying dragon, is a lizard species endemic to the Philippines. Characterized by a dull grayish brown body color and a vivid tangerine orange dewlap, this species is one of the largest of the genus Draco. It is diurnal, arboreal, and capable of gliding.

The Mindanao flying dragon inhabits regions of primary and secondary-growth forests. There appears to be a dependence on primary dipterocarp forest for this species' survival. D. mindanensis is noted for being a bioindicator for the forested regions of Mindanao.

Threatened heavily by deforestation, the IUCN has listed D. mindanensis as vulnerable. Currently, there are no specific conservation efforts being made to preserve the species. Rather, there are projects that target the protection of the habitats in which the Mindanao flying dragon lives.

Taxonomy

This species of flying dragon is classified under the kingdom Animalia, phylum Chordata, class Reptilia, order Squamata, and family Agamidae.[2]

Description

Characteristics

Draco mindanensis is a member of the genus Draco. Its body color is a dull grayish brown, almost sepia, with pale rounded spots.[3] On its back, there are about five series of whitish round spots alternating with four series of larger, more conspicuous spots.[3] The surface of this species' patagium, or the extensible fold of skin used in flight, is red in males and dusky in females.[4] Also, D. mindanensis can be distinguished from other species of Draco in the Philippines by its larger size (maximum length has been recorded at 105 mm[4]), mode of five ribs supporting its patagium, upward directed nostril,[3] lack of Y-shaped series of scales on forehead,[3] presence of lacrimal bone[5] and dorsal body coloration of pale brown with a slight greenish case in males.[4] In males of this species, the dewlap, or the inflatable loose skin under the throat, is large, triangular and narrow, and is vivid tangerine orange in coloration.[4] In females, the tip of small dewlap is cream yellow.[5]

Behavior

Draco mindanensis is diurnal and arboreal.[6] The stomach contents of D. mindanensis consist of several families of insects. However, this species is not an ant-feeding specialist like its congener, Draco volans.[6] Near Mt. Apo on Mindanao, this species was reported in sympatry with D. bimaculatus, D. cyanopterus, and D. guentheri.[4]

Habitat

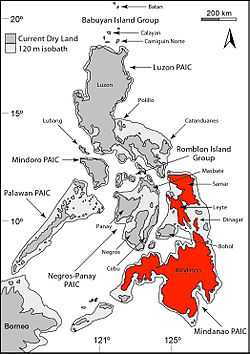

This species has been found in areas dominated by trees of the family Dipterocarpaceae in the rain forests of the Philippines.[6] In South Cotobato, Mindanao, D. mindanensis was only found in the largest dipterocarp trees.[5] Specimens have been collected at 1100 feet at the base of the Malindang Mountain in northwestern Mindanao.[6] Also, specimens have been collected in the coastal mountains (Diuata Range) of east central Mindanao.[6] Vegetation of this area was early second-growth and primary dipterocarp forest.[6]

This species has been collected on the islands of Dinagat, Leyte,and Samar at elevations of around 200 to 900 meters.[2] D. mindanensis appears to be a forest obligate species, restricted to primary and possibly mature secondary growth forest.[2] There appears to be a strong dependence on primary and secondary forest habitats that are exceedingly rare and D. mindanensis livelihood due their absence in nearby coconut groves adjacent to these forests.[5] For this very reason, experts believe that this species of Draco is the most endangered species in the Philippines.[5]

Gliding

D. mindanensis, like other members of the Draco species, is famous for its use of gliding as a form of locomotive behavior.[7] These lizards have a set of elongated ribs, which they can extend and retract. The ribs are quite flexible and apparently they are subject to a certain amount of bending.[8] Between these ribs are folds of skin that rest flat against the body when not in use, but act as wings when unfurled, allowing the Draco to catch the wind and glide.[9] Gliding ability is of daily importance and has important consequences in contexts of both natural and sexual selection.[7]

With D. mindanensis being a larger glider compared to its family members, it descends greater distances and will attain higher air velocities to reach equilibrium gliding.[7] Findings suggest that takeoff heights greater than six meters or horizontal transit distances greater than nine meters are required to achieve equilibrium glides.[7] Furthermore, in order to support its mass, glides occur at a higher velocity than smaller Draco lizards.

Flight is described in three stages: dive flight, glide flight, and ascent flight or landing phase.[8] Dive flight occurs when the lizard launches itself from a tree and there is a steep downward glide at an angle of 45 degrees.[8] The kinetic energy that develops during the dive flight is utilized in the second phase of glide flight.[8] During glide flight, the lizard's body axis and tail are straightened to maximize flight distance.[8] Finally, the third phase, ascent flight occurs. The trajectory of D. mindanensis rises so that the lizard can swoop upwards as it lands on its target.[8] Rotation of the lizard's tail plays an important role in maintaining position in the air[8]

Although, D. mindanensis is able to utilize physiological advantages to achieve top performance in flight, there are certain disadvantages. This species cannot utilize lower forest strata to the same extent as can smaller species while maintaining the ability to complete glides to adjacent trees.[7] Also, from an evolutionary standpoint, potential modification of wing area is limited by the architecture of the gliding mechanism.[7]

Conservation

Status

The Mindanao Flying Dragon is listed as Vulnerable according to the IUCN because it is suspected that a population decline, estimated to be more than 30% would be met over a ten-year period which is ongoing from the recent past to the near future, inferred from the loss of its primary and possibly mature second growth forest habitat.[2]

Threats

Habitat loss due to deforestation (including for agricultural conversion) is the major threat to this species. Forest disturbance is likely also a threat. It is not known with certainty if this species is collected for traditional medicinal use, and further studies are needed to determine this.[2]

Management

There are currently no conservation acts or projects focused directly on the perservation of D. mindanensis. Rather, there are projects and initiatives directed in the conservation of D. mindanensis rainforest habitat in the Mindanao region. D. mindanensis is found in multiple protected areas, including on Samar and Leyte.[2] In 2005, Conservation International Philippines began work in the Eastern Mindanao Corridor to conserve the area's globally significant biodiversity by establishing more protected areas and improving management of existing protected areas.[10] Another organization focusing on conservation of Mindanao Flying Dragon habitat is the Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund. This five-year investment program focuses on building alliances and civil society capacity essential for the success of conservation of this region.[11] Both of these organizations work with local governments, local NGOs, and local communities to build awareness and advocate for better corridor and protected area management.

Importance

Conservation of Draco mindanensis offers various advantages. Draco lizards have much potential as a model system for the study of diverse evolutionary phenomena including topics such as evolution of gliding performance, evolution of display structures and behavior, evolution of sexual size dimorphism and dichromatism, and the evolution of niche partitioning and community assembly.[7] The Mindanao Flying Dragon is considered a bioindicator meaning that it relies heavily on the quality of its preferred habitat, in this case being primary or good secondary-growth forest.[12] Unlike many of the other Draco species which can be found in disturbed environments such as coconut tree plantations, residential fields, etc., the Mindanao Flying Dragon is slowly becoming more difficult to find due to its habitat becoming "extinct" itself in the Philippines due to severe deforestation.[12] Thus, it is critical to document and understand the diversity and distribution of D. mindanensis in order to attempt to protect the remaining populations of it in the wild.[12]

References

- ↑ The Reptile Database. www.reptile-database.org.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 "Draco mindanensis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Stejneger, Leonhard (1908). "A new species of flying lizard from the Philippine Islands". Proc. United States Natl. Mus. 33. pp. 677–679. url=http://si-pddr.si.edu/jspui/bitstream/10088/14010/1/USNMP-33_1583_1908.pdf|publisher=Si-pddr.si.edu|accessdate=23 October 2012

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 4.4 Siler, Cameron. "Biodiversity Research & Education Outreach". Philbreo.lifedesks.org. Retrieved 23 October 2012.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 5.4 McGuire, Jimmy. "Phylogentic Systematics, Scaling Relationships, and the Evolution of Gliding Performance in Gliding Lizards (Genus Draco)". Zo.utexas.edu. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 6.5 Smith, Brian E. (1993). "Notes on Squamate Reptiles from Eastern Mindanao". Asiatic Herpetological Research (Asiatic-herpetological.org). Retrieved 2012-11-30.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 7.5 7.6 McGuire, Jimmy A., and Robert Dudley (2005). "The cost of living large: comparative gliding performance in flying lizards (Agamidae: Draco)". The American Naturalist: 93–106.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 8.2 8.3 8.4 8.5 8.6 Colbert, E.H. (1967). "Adaptations for gliding in the lizard Draco". American Museum Novitates.

- ↑ "Draco lizard". National Geographic. Retrieved 30 October 2012.

- ↑ "Eastern Mindanao Corridor". Conservation.org. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ "Critical Ecosystem Partnership Fund". Cepf.net. Retrieved 5 November 2012.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 12.2 Siler, Cameron. Interview with R.D.Mira. Personal Interview.