Djedefre

| Djedefre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Djedefra, Radjedef, Ratoises,[1] Rhampsinit, Rhauosis[2] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Red granite head of Djedefre from Abu Rawash, Musée du Louvre | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh of Egypt | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | 10 to 14 years, ca. 2575 BC, 4th Dynasty | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Khufu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Khafra | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort(s) | Hetepheres II, Khentetka | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Setka, Baka, Hernet, Neferhetepes, Hetepheres ?, Nikaudjedefre ? | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | Khufu | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Burial | Pyramid of Djedefre, Great Sphinx of Giza ?[3] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments | Pyramid of Djedefre | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Djedefre (also known as Djedefra and Radjedef) was an ancient Egyptian king (pharaoh) of 4th dynasty during the Old Kingdom. He is well known under his Hellenized name form Ratoises (by Manetho). Djedefre was the son and immediate throne successor of Khufu, the builder of the Great Pyramid of Giza; his mother is not known for sure. He was the king who introduced the royal title Sa-Rê (meaning “Son of Ra”) and the first to connect his cartouche name with the sun god Ra.

Family

He married his (half-) sister Hetepheres II. He also had another wife, Khentetka with whom he had (at least) three sons, Setka, Baka and Hernet, and one daughter, Neferhetepes. These children are attested to by statuary fragments found in the ruined mortuary temple adjoining the pyramid. Various fragmentary statues of Khentetka were found in this ruler's mortuary temple at Abu Rawash.[4] Abu Rawash actually sits at an elevation higher than the rest of Giza, making it the highest, albeit not the tallest, pyramid. Some historians claim that the "pyramid" at Abu Rawash isn't even a pyramid at all; instead, it may be a "sun temple." Archaeologist Vassil Dobrev has claimed that it may not even be Djedefre's. Excavations by the French team under Michel Valloggia have recently added another potential daughter, Hetepheres, as well as a son, Nikaudjedefre, to this.

Djedefre married his brother Kawab's widow, Hetepheres II, who was sister to both of them, and perhaps married a third brother of theirs, Khafre, after Djedefre's death.[5] Another queen, Khentetka is known to us from statue fragments in the Abu Rowash mortuary temple.[6] Known children of Djedefre are:

- Hornit (“Eldest King's Son of His Body”) known from a statue depicting him and his wife.[7]

- Baka (“Eldest King's Son”) known from a statue base found in Djedefre's mortuary temple, depicting him with his wife Hetepheres.[8]

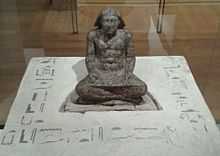

- Setka (“Eldest King's Son of His Body; Unique Servant of the King”) known from a scribe statue found in his father's pyramid complex.[9] It is possible that he ruled for a short while after his father's death; an unfinished pyramid at Zawiyet el-Arian was started for a ruler whose name ends in ka; this could have been Setka or Baka.[5]

- Neferhetepes (“King's Daughter of His Body; God's Wife”) is known from a statue fragment from Abu Rowash. Until recently, it was believed to be the mother of a pharaoh of the next dynasty, either Userkaf or Sahure.[9]

The French excavation team led by Michel Vallogia found the names of two other possible children of Djedefre in the pyramid complex:

- Nikaudjedefre (“King's Son of His Body”) was buried in Tomb F15 in Abu Rowash; it is possible that he wasn't a son of Djedefre but lived later and his title was only honorary.[9]

- Hetepheres (“King's Daughter of His Body”) was mentioned on a statue fragment.[7]

Reign

The Turin King List credits him with a rule of eight years, but the highest known year referred to during this reign appears to be the Year of his 11th cattle count. The anonymous Year of the 11th count date presumably of Djedefre was found written on the underside of one of the massive roofing-block beams which covered Khufu's southern boat-pits by Egyptian work crews.[10] Miroslav Verner notes that in the work crew's mason marks and inscriptions, "either Djedefra's throne name or his Golden Horus name occur exclusively."[11] Verner writes that the current academic opinion regarding the attribution of this date to Djedefre is disputed among Egyptologists: Rainer Stadelman, Vassil Dobrev, Peter Janosi favour dating it to Djedefre whereas Wolfgang Helck, Anthony Spalinger, Jean Vercoutter and W.S. Smith attribute this date to Khufu instead on the assumption "that the ceiling block with the date had been brought to the building site of the boat pit already in Khufu's time and placed in position [only] as late as during the burial of the funerary boat in Djedefra's time.[11]

The German scholar Dieter Arnold, in a 1981 MDAIK paper noted that the marks and inscriptions of the blocks from Khufu's boat pit seem to form a coherent collection relating to the different stages of the same building project realised by Djedefra's crews.[12] Verner stresses that such marks and inscriptions usually pertained to the breaking of the blocks in the quarry, their transportation, their storage and manipulation in the building site itself.:[13] "In this context, the attribution of just a single inscription--and what is more, the only one with a date--on all the blocks from the boat pit to somebody other than Djedefra does not seem very plausible."[14]

Verner also notes that the French-Swiss team excavating Djedefra's pyramid have discovered that this king's pyramid was really finished in his reign. According to Vallogia, Djedefre's pyramid largely made use of a natural rock promontory which represented circa 45% of its core; the side of the pyramid was 200 cubits long and its height was 125 cubits.[15] The original volume of the monument of Djedefra, hence, approximately equalled that of Menkaura's own pyramid.[16] Therefore, the argument that Djedefre enjoyed a short reign because his pyramid was unfinished is somewhat discredited.[17] This means that Djedefre likely ruled Egypt for a minimum of eleven years if the cattle count was annual or 21 years if it was biennal; Verner, himself, supports the shorter 11 year figure and notes that "the relatively few monuments and records left by Djedefra do not seem to favour a very long reign" for this king.[17]

Pyramid complex

Djedefre continued the move north in the location of pyramids by building his (now ruined) pyramid at Abu Rawash, some 8 km to the north of Giza. It is the northernmost part of the Memphite necropolis.

Some believe that the sphinx of his wife, Hetepheres II, was the first sphinx created. It was part of Djedefre's pyramid complex at Abu Rawash. In 2004, evidence that Djedefre is responsible for the building of the Sphinx at Giza in the image of his father was reported by the French Egyptologist Vassil Dobrev.[18]

While Egyptologists previously assumed that his pyramid at the heavily denuded site of Abu Rawash—some 5 miles north of Giza—was unfinished upon his death, more recent excavations from 1995 to 2005 have established that it was indeed completed.[19] The most recent evidence rather indicates that his pyramid complex was extensively plundered in later periods while "the king's statues [were] smashed as late as the 2nd century AD."[19]

Due to the poor condition of Abu Rawash, only small traces of his mortuary complex have been found; his pyramid causeway proved to run from north to south rather than the more conventional east to west while no valley temple has been found.[20] Only the rough ground plan of his mud-brick mortuary temple was traced—with some difficulty--"in the usual place on the east face of the pyramid."[20]

References

- ↑ Kim Ryholt: The political Situation in Egypt during the second intermediate Period: c. 1800 - 1550 B.C., Museum Tusculanum Press, Copenhagen 1997, ISBN 87-7289-421-0; William Gillian Waddell: Manetho (The Loeb classical Library)

- ↑ Alan B. Lloyd: Herodotus, book II.

- ↑ The riddle of the Spinx

- ↑ Aidan Dodson & Dyan Hilton, The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt, Thames & Hudson (2004), p.59

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Dodson & Hilton, p.55

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton, p.59

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Dodson & Hilton, p.58

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton, pp.56, 58

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 Dodson & Hilton, p.61

- ↑ Miroslav Verner, Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology, Archiv Orientální, Volume 69: 2001, p.375

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Verner, p.375

- ↑ Dieter Arnold, MDAIK 37 (1981), p.28

- ↑ M. Verner, Baugraffiti der Ptahscepses-Mastaba, Praha 1992. p.184

- ↑ Verner, p.376

- ↑ Michel Vallogia, Études sur l'Ancien Empire et la nécropole de Saqqara (Fs Lauer) 1997. p.418

- ↑ Vallogia, op. cit., p.418

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Verner, p.377

- ↑ Riddle of the Sphinx

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 Clayton, pp.50-51

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Clayton, p.50

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Djedefra. |

![I9 [f] f](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/h/i/e/r/hiero_I9.png)