Diplodocus

| Diplodocus Temporal range: Late Jurassic, 154–150Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Mounted D. carnegii holotype skeleton, Carnegie Museum of Natural History | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Suborder: | †Sauropodomorpha |

| Family: | †Diplodocidae |

| Subfamily: | †Diplodocinae |

| Genus: | †Diplodocus Marsh, 1878 |

| Type species | |

| Diplodocus longus Marsh, 1878 | |

| Species | |

|

D. longus Marsh, 1878 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Seismosaurus Gillette, 1991 | |

Diplodocus (/dɪˈplɒdəkəs/,[1][2] /daɪˈplɒdəkəs/,[2] or /ˌdɪploʊˈdoʊkəs/[1]) is an extinct genus of diplodocid sauropod dinosaur whose fossils were first discovered in 1877 by S. W. Williston. The generic name, coined by Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878, is a Neo-Latin term derived from Greek διπλός (diplos) "double" and δοκός (dokos) "beam",[1][3] in reference to its double-beamed chevron bones located in the underside of the tail. These bones were initially believed to be unique to Diplodocus; however, they have since then been discovered in other members of the diplodocid family and in non-diplodocid sauropods such as Mamenchisaurus.

This genus of dinosaurs lived in what is now western North America at the end of the Jurassic Period. Diplodocus is one of the more common dinosaur fossils found in the Upper Morrison Formation, a sequence of shallow marine and alluvial sediments deposited about 155 to 148 million years ago, in what is now termed the Kimmeridgian and Tithonian stages (Diplodocus itself ranged from about 154 to 150 million years ago[4]). The Morrison Formation records an environment and time dominated by gigantic sauropod dinosaurs such as Camarasaurus, Barosaurus, Apatosaurus and Brachiosaurus.[5]

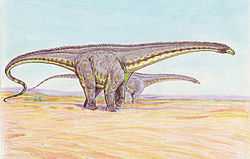

Diplodocus is among the most easily identifiable dinosaurs, with its classic dinosaur shape, long neck and tail and four sturdy legs. For many years, it was the longest dinosaur known. Its great size may have been a deterrent to the predators Allosaurus and Ceratosaurus: their remains have been found in the same strata, which suggests they coexisted with Diplodocus.

Description

One of the best-known sauropods, Diplodocus was a very large long-necked quadrupedal animal, with a long, whip-like tail. Its forelimbs were slightly shorter than its hind limbs, resulting in a largely horizontal posture. The long-necked, long-tailed animal with four sturdy legs has been mechanically compared with a suspension bridge.[6] In fact, Diplodocus is the longest dinosaur known from a complete skeleton.[6] The partial remains of D. hallorum have increased the estimated length, though not as much as previously thought; when first described in 1991, discoverer David Gillette calculated it may have been up to 54 m (177 ft) long, making it the longest known dinosaur (excluding those known from exceedingly poor remains, such as Amphicoelias). Some weight estimates ranged as high as 113 tons (125 US short tons). The estimated length was later revised downward to 33 metres (108 ft)[7] based on findings that show that Gillette had originally misplaced vertebrae 12–19 at vertebrae 20–27. The nearly complete Diplodocus skeleton at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, on which estimates of Seismosaurus are based, also was found to have had its 13th tail vertebra come from another dinosaur, throwing size estimates for Seismosaurus further off. While dinosaurs such as Supersaurus were probably longer, fossil remains of these animals are only fragmentary.[8] Modern mass estimates for Diplodocus (exclusive of D. hallorum) have tended to be in the 10 to 16 tonne (11–17.6 ton) range: 10 tonnes (11 tons);[9] 11.5 tonnes (12.7 tons);[10] 12.7 tonnes (14 tons);[11] and 16 tonnes (17.6 tons).[12]

The skull of Diplodocus was very small, compared with the size of the animal, which could reach up to 35 m (115 ft),[13] of which over 6 m (20 ft) was neck.[14] Diplodocus had small, 'peg'-like teeth that pointed forward and were only present in the anterior sections of the jaws.[15] Its braincase was small. The neck was composed of at least fifteen vertebrae and is now believed to have been generally held parallel to the ground and unable to have been elevated much past horizontal.[16]

Diplodocus had an extremely long tail, composed of about 80 caudal vertebrae,[17] which is almost double the number some of the earlier sauropods had in their tails (such as Shunosaurus with 43), and far more than contemporaneous macronarians had (such as Camarasaurus with 53). There has been speculation as to whether it may have had a defensive[18] or noisemaking (by cracking it like a coachwhip) function.[19] The tail may have served as a counterbalance for the neck. The middle part of the tail had 'double beams' (oddly shaped bones on the underside, which gave Diplodocus its name). They may have provided support for the vertebrae, or perhaps prevented the blood vessels from being crushed if the animal's heavy tail pressed against the ground. These 'double beams' are also seen in some related dinosaurs.[20]

Like other sauropods, the manus (front "feet") of Diplodocus were highly modified, with the finger and hand bones arranged into a vertical column, horseshoe-shaped in cross section. Diplodocus lacked claws on all but one digit of the front limb, and this claw was unusually large relative to other sauropods, flattened from side to side, and detached from the bones of the hand. The function of this unusually specialized claw is unknown.[21]

Discovery and species

Several species of Diplodocus were described between 1878 and 1924. The first skeleton was found at Cañon City, Colorado by Benjamin Mudge and Samuel Wendell Williston in 1877, and was named Diplodocus longus ('long double-beam'), by paleontologist Othniel Charles Marsh in 1878.[22] Diplodocus remains have since been found in the Morrison Formation of the western U.S. States of Colorado, Utah, Montana and Wyoming. Fossils of this animal are common, except for the skull, which is often missing from otherwise complete skeletons. Although not the type species, D. carnegii is the most completely known and most famous due to the large number of casts of its skeleton in museums around the world.[20]

The two Morrison Formation sauropod genera Diplodocus and Barosaurus had very similar limb bones. In the past, many isolated limb bones were automatically attributed to Diplodocus but may, in fact, have belonged to Barosaurus.[23] Fossil remains of Diplodocus have been recovered from stratigraphic zone 5 of the Morrison Formation.[24]

Valid species

- D. longus, the type species, is known from two skulls and a caudal series from the Morrison Formation of Colorado and Utah.[13]

- D. carnegii (also spelled D. carnegiei), named after Andrew Carnegie, is the best known, mainly due to a near-complete skeleton (specimen CM 84) collected by Jacob Wortman, of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and described and named by John Bell Hatcher in 1901.[25]

- D. hayi, known from a partial skeleton discovered by William H. Utterback in 1902 near Sheridan, Wyoming, was described in 1924.[26]

- D. hallorum, first described in 1991 by Gillette as Seismosaurus halli from a partial skeleton comprising vertebrae, pelvis and ribs. George Olshevsky later attempted to emend the name as S. hallorum, citing incorrect grammar on the part of the original authors, a recommendation that has been followed by others, including Carpenter (2006).[27] In 2004, a presentation at the annual conference of the Geological Society of America made a case for Seismosaurus being a junior synonym of Diplodocus.[28] This was followed by a much more detailed publication in 2006, which not only renamed the species Diplodocus hallorum, but also speculated that it could prove to be the same as D. longus.[29] The position that D. hallorum should be regarded as a specimen of D. longus was also taken by the authors of a redescription of Supersaurus, refuting a previous hypothesis that Seismosaurus and Supersaurus were the same.[30]

Nomina dubia (doubtful species)

- D. lacustris is a nomen dubium, named by Marsh in 1884, from remains of a smaller animal from Morrison, Colorado.[31] These remains are now believed to have been from an immature animal, rather than from a separate species.[32]

Paleobiology

Due to a wealth of skeletal remains, Diplodocus is one of the best-studied dinosaurs. Many aspects of its lifestyle have been subjects of various theories over the years.[20]

Habitat

Marsh and then Hatcher[33] assumed the animal was aquatic, because of the position of its nasal openings at the apex of the cranium. Similar aquatic behavior was commonly depicted for other large sauropods such as Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus. However, a 1951 study by Kenneth A. Kermack indicates that sauropods probably could not have breathed through their nostrils when the rest of the body was submerged, as the water pressure on the chest wall would be too great.[34] Since the 1970s, general consensus has the sauropods as firmly terrestrial animals, browsing on trees, ferns and bushes.[35]

Posture

The depiction of Diplodocus posture has changed considerably over the years. For instance, a classic 1910 reconstruction by Oliver P. Hay depicts two Diplodocus with splayed lizard-like limbs on the banks of a river. Hay argued that Diplodocus had a sprawling, lizard-like gait with widely splayed legs,[36] and was supported by Gustav Tornier. However, this hypothesis was contested by William Jacob Holland, who demonstrated that a sprawling Diplodocus would have needed a trench to pull its belly through.[37] Finds of sauropod footprints in the 1930s eventually put Hay's theory to rest.[35]

Later, diplodocids were often portrayed with their necks held high up in the air, allowing them to graze from tall trees. Studies using computer models have shown that neutral posture of the neck was horizontal, rather than vertical, and scientists such as Kent Stephens have used this to argue that sauropods including Diplodocus did not raise their heads much above shoulder level.[38][39] A nuchal ligament may have held the neck in this position.[38] However, subsequent studies demonstrated that all tetrapods appear to hold their necks at the maximum possible vertical extension when in a normal, alert posture, and argued that the same would hold true for sauropods barring any unknown, unique characteristics that set the soft tissue anatomy of their necks apart from other animals. One of the sauropod models in this study was Diplodocus, which they found would have held its neck at about a 45-degree angle with the head pointed downwards in a resting posture.[40]

As with the related genus Barosaurus, the very long neck of Diplodocus is the source of much controversy among scientists. A 1992 Columbia University study of Diplodocid neck structure indicated that the longest necks would have required a 1.6 ton heart — a tenth of the animal's body weight. The study proposed that animals like these would have had rudimentary auxiliary 'hearts' in their necks, whose only purpose was to pump blood up to the next 'heart'.[6]

While the long neck has traditionally been interpreted as a feeding adaptation, it was also suggested[41] that the oversized neck of Diplodocus and its relatives may have been primarily a sexual display, with any other feeding benefits coming second. However, a 2011 study refuted this idea in detail.[42]

Diet and feeding

Diplodocus has highly unusual teeth compared to other sauropods. The crowns are long and slender, elliptical in cross-section, while the apex forms a blunt triangular point.[15] The most prominent wear facet is on the apex, though unlike all other wear patterns observed within sauropods, Diplodocus wear patterns are on the labial (cheek) side of both the upper and lower teeth.[15] What this means is Diplodocus and other diplodocids had a radically different feeding mechanism than other sauropods. Unilateral branch stripping is the most likely feeding behavior of Diplodocus,[43][44][45] as it explains the unusual wear patterns of the teeth (coming from tooth–food contact). In unilateral branch stripping, one tooth row would have been used to strip foliage from the stem, while the other would act as a guide and stabilizer. With the elongated preorbital (in front of the eyes) region of the skull, longer portions of stems could be stripped in a single action.[15] Also the palinal (backwards) motion of the lower jaws could have contributed two significant roles to feeding behaviour: 1) an increased gape, and 2) allowed fine adjustments of the relative positions of the tooth rows, creating a smooth stripping action.[15]

Young et al. (2012) used bio-mechanical modelling to examine the performance of the Diplodocus skull. It was concluded that the proposal that its dentition was used of bark-stripping was not supported by the data, which showed that under that scenario, the skull and teeth would undergo extreme stresses. However the hypotheses of branch-stripping and/or precision biting were both shown to be bio-mechanically plausible feeding behaviors.[46] Diplodocus teeth were also continually replaced throughout its life, usually in less than 35 days, as was discovered by Michael D'Emic et al. Within each tooth socket, as many as five replacement teeth were developing to replace the next one. Studies of the teeth also reveal that it preferred different vegetation than the other sauropods of the Morrison, such as Camarasaurus. This may have better allowed the various species of sauropod to exist without competition.[47]

With a laterally and dorsoventrally flexible neck, and the possibility of using its tail and rearing up on its hind limbs (tripodal ability), Diplodocus would have had the ability to browse at many levels (low, medium, and high), up to approximately 10 metres (33 ft) from the ground.[48] The neck's range of movement would have also allowed the head to graze below the level of the body, leading some scientists to speculate on whether Diplodocus grazed on submerged water plants, from riverbanks. This concept of the feeding posture is supported by the relative lengths of front and hind limbs. Furthermore, its peglike teeth may have been used for eating soft water plants.[38]

In 2010, Whitlock et al. described a juvenile skull of Diplodocus (CM 11255) that differs greatly from adult skulls of the same genus: its snout is not blunt, and the teeth are not confined to the front of the snout. These differences suggest that adults and juveniles were feeding differently. Such an ecological difference between adults and juveniles had not been previously observed in sauropodomorphs.[49]

Other anatomical aspects

The head of Diplodocus has been widely depicted with the nostrils on top due to the position of the nasal openings at the apex of the skull. There has been speculation over whether such a configuration meant that Diplodocus may have had a trunk.[50] A 2006 study[51] surmised there was no paleoneuroanatomical evidence for a trunk. It noted that the facial nerve in an animal with a trunk, such as an elephant, is large as it innervates the trunk. The evidence suggests that the facial nerve is very small in Diplodocus. Studies by Lawrence Witmer (2001) indicated that, while the nasal openings were high on the head, the actual, fleshy nostrils were situated much lower down on the snout.[52]

Recent discoveries have suggested that Diplodocus and other diplodocids may have had narrow, pointed keratinous spines lining their back, much like those on an iguana.[53][54] This radically different look has been incorporated into recent reconstructions, notably Walking with Dinosaurs. It is unknown exactly how many diplodocids had this trait, and whether it was present in other sauropods.[55]

Reproduction and growth

While there is no evidence for Diplodocus nesting habits, other sauropods such as the titanosaurian Saltasaurus have been associated with nesting sites.[56][57] The titanosaurian nesting sites indicate that may have laid their eggs communally over a large area in many shallow pits, each covered with vegetation. It is possible that Diplodocus may have done the same. The documentary Walking with Dinosaurs portrayed a mother Diplodocus using an ovipositor to lay eggs, but it was pure speculation on the part of the documentary.[55]

Based on a number of bone histology studies, Diplodocus, along with other sauropods, grew at a very fast rate, reaching sexual maturity at just over a decade, and continued to grow throughout their lives.[58][59][60]

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Diplodocus and modern birds and reptiles suggest that it may have been cathemeral, active throughout the day at short intervals.[61]

Classification

Diplodocus is both the type genus of, and gives its name to Diplodocidae, the family to which it belongs.[31] Members of this family, while still massive, are of a markedly more slender build when compared with other sauropods, such as the titanosaurs and brachiosaurs. All are characterised by long necks and tails and a horizontal posture, with forelimbs shorter than hindlimbs. Diplodocids flourished in the Late Jurassic of North America and possibly Africa.[17]

A subfamily, Diplodocinae, was erected to include Diplodocus and its closest relatives, including Barosaurus. More distantly related is the contemporaneous Apatosaurus, which is still considered a diplodocid although not a diplodocine, as it is a member of the subfamily Apatosaurinae.[62][63] The Portuguese Dinheirosaurus and the African Tornieria have also been identified as close relatives of Diplodocus by some authors.[64][65]

The Diplodocoidea comprises the diplodocids, as well as dicraeosaurids, rebbachisaurids, Suuwassea,[62][63] Amphicoelias[65] and possibly Haplocanthosaurus,[66] and/or the nemegtosaurids.[14] This clade is the sister group to, Camarasaurus, brachiosaurids and titanosaurians; the Macronaria.[14][66]

The following cladogram is based on the phylogenetic analysis conducted by Whitlock in 2011, showing the relationships of Diplodocus among the other genera assigned to the taxon Diplodocidae:[67]

| Diplodocidae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |

In popular culture

.001_-_London.JPG)

Diplodocus has been a famous and much-depicted dinosaur as it has been on display in more places than any other sauropod dinosaur.[68] Much of this has probably been due to its wealth of skeletal remains and former status as the longest dinosaur. However, the donation of many mounted skeletal casts by industrialist Andrew Carnegie to potentates around the world at the beginning of the twentieth century[69] did much to familiarize it to people worldwide. Casts of Diplodocus skeletons are still displayed in many museums worldwide, including an unusual D. hayi in the Houston Museum of Natural Science, and D. carnegii in a number of institutions.[35]

This includes donations by Carnegie or his trust to:[69]

- The Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh (original, unveiled in 1907)

- The Natural History Museum in London (replica, unveiled on 12 May 1905)

- The Museum für Naturkunde in Berlin, Germany (replica, unveiled in early May, 1908)

- The National Natural History Museum in Paris, France (replica, unveiled on 15 June 1908)

- The Natural History Museum in Vienna, Austria (replica, unveiled in 1909)

- The Museum for Paleontology and Geology in Bologna, Italy (replica, unveiled in 1909). Skulls from this cast (i.e., 'second-generation') are on display in museums in Milan and Naples.

- The Zoological Museum of the Russian Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg, Russia (replica, unveiled in 1910)

- The Museo de la Plata in La Plata near Buenos Aires, Argentina (replica, unveiled in 1912)

- The National Natural History Museum in Madrid, Spain (replica, unveiled in November 1913)[70]

- The Museo de Paleontología in Mexico City (replica, unveiled in 1930)

- The Paleontological Museum in Munich, Germany (replica, donated in 1932 and still unmounted)

This project, along with its association with 'big science', philanthropism and capitalism, drew much public attention in Europe. The German satirical weekly Kladderadatsch devoted a poem to the dinosaur:

... Auch ein viel älterer Herr noch muß

Den Wanderburschen spielen

An mehrere Monarchen ...

Er ist genannt Diplodocus‚ und zählt zu den Fossilen

Herr Carnegie verpackt ihn froh

In riesengroße Archen

Und schickt als Geschenk ihn so

(Translation: ... But even a much older gent • Sees itself forced to wander • Goes by the name Diplodocus • And belongs among the fossils • Mr. Carnegie packs him joyfully • In giant arcs • And sends him as gift this way • To multiple monarchs ...)[71] "Le diplodocus" became a generic term for sauropods in French, much as "brontosaur" is in English.[72]

D. longus is displayed the Senckenberg Museum in Frankfurt (a skeleton made up of several specimens, donated in 1907 by the American Museum of Natural History), Germany.[73][74] A mounted and more complete skeleton of D. longus is at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C.,[75] while a mounted skeleton of D. hallorum (formerly Seismosaurus), which may be the same as D. longus, can be found at the New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.[76]

Diplodocus has been a frequent subject in dinosaur films, both factual and fictional. It was featured in the second episode of the award-winning BBC television series Walking with Dinosaurs. The episode "Time of the Titans" follows the life of a simulated Diplodocus 152 million years ago. In literature, James A. Michener's book Centennial has a chapter devoted to Diplodocus, narrating the life and death of one individual.[69]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Simpson, John; Edmund Weiner (eds.) (1989). The Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-861186-2.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Pickett, Joseph P. et al. (eds.) (2000). The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language (4th ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 0-395-82517-2.

- ↑ "diplodocus". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F., (1999). "Biostratigraphy of dinosaurs in the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation of the Western Interior, U.S.A." Pp. 77–114 in Gillette, D.D. (ed.), Vertebrate Paleontology in Utah. Utah Geological Survey Miscellaneous Publication 99-1.

- ↑ Turner, C.E. and Peterson, F. (2004). "Reconstruction of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation extinct ecosystem—a synthesis". Sedimentary Geology 167: 309–355. doi:10.1016/j.sedgeo.2004.01.009.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 Lambert D. (1993). The Ultimate Dinosaur Book. DK Publishing. ISBN 0-86438-417-3.

- ↑ Lucas, Herne, Heckert, Hunt & Sullivan (2004). "Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, a Late Jurassic Sauropod". Proceedings, Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology 36 (5): 422..

- ↑ Wedel, M.J. and Cifelli, R.L. Sauroposeidon: Oklahoma's Native Giant. 2005. Oklahoma Geology Notes 65:2.

- ↑ Dodson, P., Behrensmeyer, A.K., Bakker, R.T., and McIntosh, J.S. (1980). "Taphonomy and paleoecology of the dinosaur beds of the Jurassic Morrison Formation". Paleobiology 6: 208–232. JSTOR 240035.

- ↑ Paul, G.S. (1994). Big sauropods – really, really big sauropods. The Dinosaur Report, The Dinosaur Society Fall:12–13.

- ↑ Foster, J.R. (2003). Paleoecological Analysis of the Vertebrate Fauna of the Morrison Formation (Upper Jurassic), Rocky Mountain Region, U.S.A. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science:Albuquerque, New Mexico. Bulletin 23.

- ↑ Coe, M.J., Dilcher, D.L., Farlow, J.O., Jarzen, D.M., and Russell, D.A. "Dinosaurs and land plants". In Friis, E.M., Chaloner, W.G., and Crane, P.R. The Origins of Angiosperms and Their Biological Consequences. Cambridge University Press. pp. 225–258. ISBN 0-521-32357-6.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 Upchurch P, Barrett PM, Dodson P (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H. The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press. p. 305. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Upchurch P, Barrett PM, Dodson P (2004). "Sauropoda". In Weishampel DB, Dodson P, Osmólska H. The Dinosauria (2nd Edition). University of California Press. p. 316. ISBN 0-520-24209-2.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Upchurch, P. & Barrett, P.M. (2000). "The evolution of sauropod feeding mechanism". In Sues, Hans Dieter. Evolution of Herbivory in Terrestrial Vertebrates. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-59449-9.

- ↑ Stevens, K.A. & Parrish, M. (1999). Neck Posture and Feeding Habits of Two Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaurs 284 (5415). Science. pp. 798–800. doi:10.1126/science.284.5415.798. PMID 10221910.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Wilson JA (2005). "Overview of Sauropod Phylogeny and Evolution". In Rogers KA & Wilson JA(eds). The Sauropods:Evolution and Paleobiology. Indiana University Press. pp. 15–49. ISBN 0-520-24623-3.

- ↑ Holland WJ (1915). "Heads and Tails: a few notes relating to the structure of sauropod dinosaurs". Annals of the Carnegie Museum 9: 273–278.

- ↑ Myhrvold NP and Currie PJ (1997). "Supersonic sauropods? Tail dynamics in the diplodocids". Paleobiology 23: 393–409.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 Benton, Michael J. (2012). Prehistoric Life. Dorling Kindersley. pp. 268–269. ISBN 978-0-7566-9910-9.

- ↑ Bonnan, M. F. (2003). The evolution of manus shape in sauropod dinosaurs: implications for functional morphology, forelimb orientation, and phylogeny 23 (3). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. pp. 595–613. doi:10.1671/A1108.

- ↑ Marsh OC (1878). "Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part I". American Journal of Science 3: 411–416.

- ↑ McIntosh (2005). "The Genus Barosaurus (Marsh)". In Carpenter, Kenneth and Tidswell, Virginia (ed.). Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 38–77. ISBN 0-253-34542-1.

- ↑ Foster, J. (2007). "Appendix." Jurassic West: The Dinosaurs of the Morrison Formation and Their World. Indiana University Press. pp. 327–329.

- ↑ Brezinski, D. K.; Kollar, A. D. (2008). "Geology of the Carnegie Museum Dinosaur Quarry Site of Diplodocus carnegii, Sheep Creek, Wyoming". Annals of Carnegie Museum 77 (2): 243. doi:10.2992/0097-4463-77.2.243.

- ↑ Holland WJ. The skull of Diplodocus. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum IX; 379–403 (1924).

- ↑ Carpenter, K. (2006). "Biggest of the big: a critical re-evaluation of the mega-sauropod Amphicoelias fragillimus." In Foster, J.R. and Lucas, S.G., eds., 2006, Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Jurassic Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science Bulletin 36: 131–138.

- ↑ Lucas S, Herne M, Heckert A, Hunt A, and Sullivan R. Reappraisal of Seismosaurus, A Late Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaur from New Mexico. The Geological Society of America, 2004 Denver Annual Meeting (7–10 November 2004). Retrieved on 2007-05-24.

- ↑ Lucas, S.G., Spielman, J.A., Rinehart, L.A., Heckert, A.B., Herne, M.C., Hunt, A.P., Foster, J.R., and Sullivan, R.M. (2006). "Taxonomic status of Seismosaurus hallorum, a Late Jurassic sauropod dinosaur from New Mexico". In Foster, J.R., and Lucas, S.G. Paleontology and Geology of the Upper Morrison Formation. New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science (bulletin 36). pp. 149–161. ISSN 1524-4156.

- ↑ Lovelace, David M.; Hartman, Scott A.; and Wahl, William R. (2007). "Morphology of a specimen of Supersaurus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda) from the Morrison Formation of Wyoming, and a re-evaluation of diplodocid phylogeny". Arquivos do Museu Nacional 65 (4): 527–544.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Marsh, O.C. 1884. Principal characters of American Jurassic dinosaurs. Part VII. On the Diplodocidae, a new family of the Sauropoda. American Journal of Science 3: 160–168.

- ↑ Upchurch, P., Barrett, P.M., and Dodson, P. (2004). "Sauropoda". In D. B. Weishampel, P. Dodson, and H. Osmólska. The Dinosauria (2nd edition). University of California Press. pp. 259–322. ISBN 0-520-25408-2.

- ↑ Hatcher JB. "Diplodocus (Marsh): Its osteology, taxonomy, and probable habits, with a restoration of the skeleton,". Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, vol. 1 (1901), pp. 1–63

- ↑ Kermack, Kenneth A. (1951). "A note on the habits of sauropods". Annals and Magazine of Natural History 12 (4): 830–832.

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 Gangewere, J.R. (1999). "Diplodocus carnegii". Carnegie Magazine.

- ↑ Hay, Dr. Oliver P., "On the Habits and Pose of the Sauropod Dinosaurs, especially of Diplodocus." The American Naturalist, Vol. XLII, Oct. 1908

- ↑ Holland, Dr. W. J., "A Review of Some Recent Criticisms of the Restorations of Sauropod Dinosaurs Existing in the Museums of the United States, with Special Reference to that of Diplodocus carnegii in the Carnegie Museum", The American Naturalist, 44:259–283. 1910.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 Stevens KA, Parrish JM (2005). "Neck Posture, Dentition and Feeding Strategies in Jurassic Sauropod Dinosaurs". In Carpenter, Kenneth and Tidswell, Virginia (ed.). Thunder Lizards: The Sauropodomorph Dinosaurs. Indiana University Press. pp. 212–232. ISBN 0-253-34542-1.

- ↑ Upchurch, P, et al. (2000). "Neck Posture of Sauropod Dinosaurs" (PDF). Science 287 (5453): 547b. doi:10.1126/science.287.5453.547b. Retrieved 2006-11-28.

- ↑ Taylor, M.P., Wedel, M.J., and Naish, D. (2009). "Head and neck posture in sauropod dinosaurs inferred from extant animals". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 54 (2): 213–220. doi:10.4202/app.2009.0007.

- ↑ Senter, P. (2006). "Necks for Sex: Sexual Selection as an Explanation for Sauropod Neck Elongation". Journal of Zoology 271 (1): 45–53. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2006.00197.x.

- ↑ Taylor, M.P., Hone, D.W.E., Wedel, M.J. and Naish, D. (2011). "The long necks of sauropods did not evolve primarily through sexual selection". Journal of Zoology 285 (2): 151–160. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.2011.00824.x.

- ↑ Norman, D.B. (1985). "The illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs". London: Salamander Books Ltd

- ↑ Dodson, P. (1990). "Sauropod paleoecology". In Weishampel, D.B., Dodson, P. & Osmólska, H. The Dinosauria" 1st Edition. University of California Press. ASIN B008UBRHZM.

- ↑ Barrett, P.M. & Upchurch, P. (1994). Feeding mechanisms of Diplodocus. Gaia 10, 195–204

- ↑ Young, Mark T.; Emily J. Rayfield & Casey M. Holliday & Lawrence M. Witmer & David J. Button & Paul Upchurch & Paul M. Barrett (28 June 2012). "Cranial biomechanics of Diplodocus (Dinosauria, Sauropoda): testing hypotheses of feeding behaviour in an extinct megaherbivore". Naturwissenschaften 99: 637–643.

- ↑ D’Emic, M. D.; Whitlock, J. A.; Smith, K. M.; Fisher, D. C.; Wilson, J. A. (2013). "Evolution of high tooth replacement rates in sauropod dinosaurs". In Evans, A. R. PLoS ONE 8 (7): e69235. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0069235. PMC 3714237. PMID 23874921.

- ↑ Barrett, P.M. & Upchurch, P. (2005). "Sauropodomorph Diversity through Time, Paleoecological and Macroevolutionary Implications". In Curry, K. C., Wilson, J. A. The Sauropods: Evolution and Paleobiology. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-24623-3.

- ↑ Whitlock, John A.; Wilson, Jeffrey A. & Lamanna, Matthew C. (March 2010). "Description of a Nearly Complete Juvenile Skull of Diplodocus (Sauropoda: Diplodocoidea) from the Late Jurassic of North America". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology (2) 30 (2): 442–457. doi:10.1080/02724631003617647.

- ↑ Bakker, Robert T. (1986) The Dinosaur Heresies: New Theories Unlocking the Mystery of the Dinosaurs and their Extinction. New York: Morrow.

- ↑ Knoll, F., Galton, P.M., López-Antoñanzas, R. (2006). "Paleoneurological evidence against a proboscis in the sauropod dinosaur Diplodocus". Geobios 39 (2): 215–221. doi:10.1016/j.geobios.2004.11.005.

- ↑ Lawrence M. Witmer et al. (2001). "Nostril Position in Dinosaurs and other Vertebrates and its Significance for Nasal Function". Science 293: 850–853. doi:10.1126/science.1062681. PMID 11486085.

- ↑ Czerkas, S. A. (1993). "Discovery of dermal spines reveals a new look for sauropod dinosaurs." Geology 20, 1068–1070

- ↑ Czerkas, S. A. (1994). "The history and interpretation of sauropod skin impressions." In Aspects of Sauropod Paleobiology (M. G. Lockley, V. F. dos Santos, C. A. Meyer, and A. P. Hunt, Eds.), Gaia No. 10. (Lisbon, Portugal).

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 Haines, T., James, J. Time of the Titans. ABC Online.

- ↑ Walking on Eggs: The Astonishing Discovery of Thousands of Dinosaur Eggs in the Badlands of Patagonia, by Luis Chiappe and Lowell Dingus. 19 June 2001, Scribner

- ↑ Grellet-Tinner, Chiappe, & Coria (2004). "Eggs of titanosaurid sauropods from the Upper Cretaceous of Auca Mahuevo (Argentina)". Canadian Journal of Earth Science 41 (8): 949–960. doi:10.1139/e04-049.

- ↑ Sander, P. M. (2000). "Long bone histology of the Tendaguru sauropods: Implications for growth and biology". Paleobiology 26 (3): 466–488. JSTOR 2666121.

- ↑ Sander, P. M., N. Klein, E. Buffetaut, G. Cuny, V. Suteethorn, and J. Le Loeuff (2004). "Adaptive radiation in sauropod dinosaurs: Bone histology indicates rapid evolution of giant body size through acceleration". Organisms, Diversity & Evolution 4 (3): 165–173. doi:10.1016/j.ode.2003.12.002.

- ↑ Sander, P. M., and N. Klein (2005). "Developmental plasticity in the life history of a prosauropod dinosaur". Science 310 (5755): 1800–1802. doi:10.1126/science.1120125. PMID 16357257.

- ↑ Schmitz, L.; Motani, R. (2011). "Nocturnality in Dinosaurs Inferred from Scleral Ring and Orbit Morphology". Science 332. doi:10.1126/science.1200043. PMID 21493820.

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Taylor, M.P. & Naish, D. (2005). "The phylogenetic taxonomy of Diplodocoidea (Dinosauria: Sauropoda)". PaleoBios 25 (2): 1–7. ISSN 0031-0298.

- ↑ 63.0 63.1 Harris, J.D. (2006). "The significance of Suuwassea emiliae (Dinosauria: Sauropoda) for flagellicaudatan intrarelationships and evolution". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology 4 (2): 185–198. doi:10.1017/S1477201906001805.

- ↑ Bonaparte, J.F. & Mateus, O. 1999. A new diplodocid, Dinheirosaurus lourinhanensis gen. et sp. nov., from the Late Jurassic beds of Portugal. Revista del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales. 5(2) 13–29. (download here)

- ↑ 65.0 65.1 Rauhut, O.W.M., Remes, K., Fechner, R., Cladera, G., & Puerta, P. (2005). "Discovery of a short-necked sauropod dinosaur from the Late Jurassic period of Patagonia". Nature 435 (7042): 670–672. doi:10.1038/nature03623. PMID 15931221.

- ↑ 66.0 66.1 Wilson, J. A. (2002). "Sauropod dinosaur phylogeny: critique and cladistica analysis". Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society 136 (2): 217–276. doi:10.1046/j.1096-3642.2002.00029.x.

- ↑ Whitlock, J.A. (2011). "A phylogenetic analysis of Diplodocoidea (Saurischia: Sauropoda)." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, Article first published online: 12 January 2011.

- ↑ "Diplodocus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 58–59. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- ↑ 69.0 69.1 69.2 Rea, Tom (2001). Bone Wars. The Excavation and Celebrity of Andrew Carnegie's Dinosaur. Pittsburgh University Press. See particularly pages 1–11 and 198–216.

- ↑ Pérez-Garcia, Adán & Sánchez Chillón, B., "Historia de Diplodocus carnegii del MNCN: primer esqueleto de dinosaurio en la Peninsula Iberica", Revista Española de Paleontologiá 24(2), pp. 133–148.

- ↑ "Die Wanderbursche", in: Kladderadatsch, 7 May 1908

- ↑ Russell, Dale A. (1988). An Odyssey in Time: the Dinosaurs of North America. NorthWord Press, Minocqua, WI. p. 76.

- ↑ Sachs, Sven (2001). "Diplodocus - Ein Sauropode aus dem Oberen Jura (Morrison-Formation) Nordamerikas", Natur und Museum 131(5), pp. 133–150.

- ↑ Beasley, Walter (1907). "An American Dinosaur for Germany." The World Today, August 1907: 846-849.

- ↑ "Dinosaur Collections". National Museum of Natural History. 2008.

- ↑ "Age of Giants Hall". New Mexico Museum of Natural History and Science.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Diplodocus. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Diplodocus |

- Diplodocus in the Dino Directory

- Museo Nacional de Ciencias Naturales, Madrid

- Diplodocus Marsh, by J.B. Hatcher 1901 – Its Osteology, Taxonomy, and Probable Habits, with a Restoration of the Skeleton. Memoirs of the Carnegie Museum, Volume 1, Number 1, 1901. Full text, Free to read.

- Carnegie Museum of Natural History – History

- Skeletal restorations of diplodocids including D. carnegii, D. longus, and D. hallorum, from Scott Hartman's Skeletal Drawing website.

- Chapter 5: The Amphibious Dinosaurs – Brontosaurus, Diplodocusw, etc. Sub-Order Opisthocœlia (Cetiosauria or Sauropoda) by W. D. Matthew, who is credited amongst other accomplishments as authorship of the family Dromaeosauridae, and former Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology at the American Museum of Natural History in New York; Originally published in 1915