Dihedral group

| Algebraic structure → Group theory Group theory |

|---|

|

Modular groups

|

Infinite dimensional Lie group

|

In mathematics, a dihedral group is the group of symmetries of a regular polygon, including both rotations and reflections.[1] Dihedral groups are among the simplest examples of finite groups, and they play an important role in group theory, geometry, and chemistry. It is well-known and easy to prove that a group generated by two involutions on a finite domain is a dihedral group.

Notation

There are two competing notations for the dihedral group associated to a polygon with n sides. In geometry the group is denoted Dn, while in algebra the same group is denoted by D2n to indicate the number of elements. Coxeter notation is another notation, denoting the reflectional dihedral symmetry as [n], order 2n, and rotational dihedral symmetry as [n]+, order n. Orbifold notation gives the reflective symmetry as *n• and rotational symmetry as n•.

In this article, Dn (and sometimes Dihn) refers to the symmetries of a regular polygon with n sides.

Definition

Elements

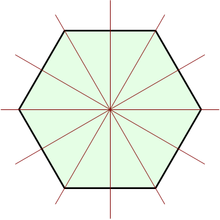

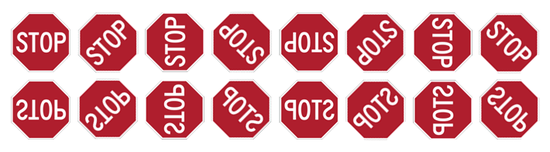

A regular polygon with n sides has 2n different symmetries: n rotational symmetries and n reflection symmetries. The associated rotations and reflections make up the dihedral group Dn. If n is odd each axis of symmetry connects the midpoint of one side to the opposite vertex. If n is even there are n/2 axes of symmetry connecting the midpoints of opposite sides and n/2 axes of symmetry connecting opposite vertices. In either case, there are n axes of symmetry altogether and 2n elements in the symmetry group. Reflecting in one axis of symmetry followed by reflecting in another axis of symmetry produces a rotation through twice the angle between the axes. The following picture shows the effect of the sixteen elements of D8 on a stop sign:

The first row shows the effect of the eight rotations, and the second row shows the effect of the eight reflections.

Group structure

As with any geometric object, the composition of two symmetries of a regular polygon is again a symmetry. This operation gives the symmetries of a polygon the algebraic structure of a finite group.

The following Cayley table shows the effect of composition in the group D3 (the symmetries of an equilateral triangle). R0 denotes the identity; R1 and R2 denote counterclockwise rotations by 120 and 240 degrees; and S0, S1, and S2 denote reflections across the three lines shown in the picture to the right.

| R0 | R1 | R2 | S0 | S1 | S2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| R0 | R0 | R1 | R2 | S0 | S1 | S2 |

| R1 | R1 | R2 | R0 | S1 | S2 | S0 |

| R2 | R2 | R0 | R1 | S2 | S0 | S1 |

| S0 | S0 | S2 | S1 | R0 | R2 | R1 |

| S1 | S1 | S0 | S2 | R1 | R0 | R2 |

| S2 | S2 | S1 | S0 | R2 | R1 | R0 |

For example, S2S1 = R1 because the reflection S1 followed by the reflection S2 results in a 120-degree rotation. (This is the normal backwards order for composition.) Note that the composition operation is not commutative.

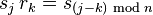

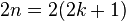

In general, the group Dn has elements R0,...,Rn−1 and S0,...,Sn−1, with composition given by the following formulae:

In all cases, addition and subtraction of subscripts should be performed using modular arithmetic with modulus n.

Matrix representation

If we center the regular polygon at the origin, then elements of the dihedral group act as linear transformations of the plane. This lets us represent elements of Dn as matrices, with composition being matrix multiplication. This is an example of a (2-dimensional) group representation.

For example, the elements of the group D4 can be represented by the following eight matrices:

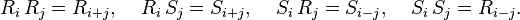

In general, the matrices for elements of Dn have the following form:

Rk is a rotation matrix, expressing a counterclockwise rotation through an angle of 2πk ⁄ n. Sk is a reflection across a line that makes an angle of πk ⁄ n with the x-axis.

Small dihedral groups

For n = 1 we have Dih1. This notation is rarely used except in the framework of the series, because it is equal to Z2. For n = 2 we have Dih2, the Klein four-group. Both are exceptional within the series:

- They are abelian; for all other values of n the group Dihn is not abelian.

- They are not subgroups of the symmetric group Sn, corresponding to the fact that 2n > n ! for these n.

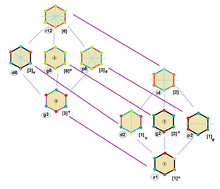

The cycle graphs of dihedral groups consist of an n-element cycle and n 2-element cycles. The dark vertex in the cycle graphs below of various dihedral groups stand for the identity element, and the other vertices are the other elements of the group. A cycle consists of successive powers of either of the elements connected to the identity element.

|

Dih4 |

The dihedral group as symmetry group in 2D and rotation group in 3D

An example of abstract group Dihn, and a common way to visualize it, is the group Dn of Euclidean plane isometries which keep the origin fixed. These groups form one of the two series of discrete point groups in two dimensions. Dn consists of n rotations of multiples of 360°/n about the origin, and reflections across n lines through the origin, making angles of multiples of 180°/n with each other. This is the symmetry group of a regular polygon with n sides (for n ≥ 3; this extends to the cases n = 1 and n = 2 where we have a plane with respectively a point offset from the "center" of the "1-gon" and a "2-gon" or line segment).

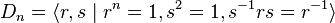

Dihedral group Dn is generated by a rotation r of order n and a reflection s of order 2 such that

In geometric terms: in the mirror a rotation looks like an inverse rotation.

In terms of complex numbers: multiplication by  and complex conjugation.

and complex conjugation.

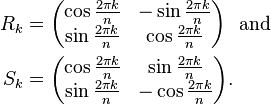

In matrix form, by setting

and defining  and

and  for

for  we can write the product rules for Dn as

we can write the product rules for Dn as

(Compare coordinate rotations and reflections.)

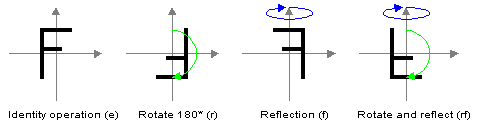

The dihedral group D2 is generated by the rotation r of 180 degrees, and the reflection s across the x-axis. The elements of D2 can then be represented as {e, r, s, rs}, where e is the identity or null transformation and rs is the reflection across the y-axis.

D2 is isomorphic to the Klein four-group.

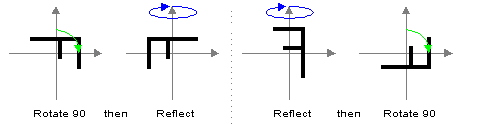

For n>2 the operations of rotation and reflection in general do not commute and Dn is not abelian; for example, in D4, a rotation of 90 degrees followed by a reflection yields a different result from a reflection followed by a rotation of 90 degrees.

Thus, beyond their obvious application to problems of symmetry in the plane, these groups are among the simplest examples of non-abelian groups, and as such arise frequently as easy counterexamples to theorems which are restricted to abelian groups.

The 2n elements of Dn can be written as e, r, r2, ..., rn−1, s, r s, r2 s, ..., rn−1 s. The first n listed elements are rotations and the remaining n elements are axis-reflections (all of which have order 2). The product of two rotations or two reflections is a rotation; the product of a rotation and a reflection is a reflection.

So far, we have considered Dn to be a subgroup of O(2), i.e. the group of rotations (about the origin) and reflections (across axes through the origin) of the plane. However, notation Dn is also used for a subgroup of SO(3) which is also of abstract group type Dihn: the proper symmetry group of a regular polygon embedded in three-dimensional space (if n ≥ 3). Such a figure may be considered as a degenerate regular solid with its face counted twice. Therefore it is also called a dihedron (Greek: solid with two faces), which explains the name dihedral group (in analogy to tetrahedral, octahedral and icosahedral group, referring to the proper symmetry groups of a regular tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron respectively).

Examples of 2D dihedral symmetry

-

2D D6 symmetry – The Red Star of David

-

2D D24 symmetry – Ashoka Chakra, as depicted on the National flag of the Republic of India.

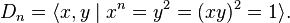

Equivalent definitions

Further equivalent definitions of Dihn are:

- The automorphism group of the graph consisting only of a cycle with n vertices (if n ≥ 3).

- The group with presentation

- or

- From the second presentation follows that Dihn belongs to the class of Coxeter groups.

- The semidirect product of cyclic groups Zn and Z2, with Z2 acting on Zn by inversion (thus, Dihn always has a normal subgroup isomorphic to the group Zn)

is isomorphic to Dihn if

is isomorphic to Dihn if  is the identity and

is the identity and  is inversion.

is inversion.

Properties

The properties of the dihedral groups Dihn with n ≥ 3 depend on whether n is even or odd. For example, the center of Dihn consists only of the identity if n is odd, but if n is even the center has two elements, namely the identity and the element rn / 2 (with Dn as a subgroup of O(2), this is inversion; since it is scalar multiplication by −1, it is clear that it commutes with any linear transformation).

For odd n, abstract group Dih2n is isomorphic with the direct product of Dihn and Z2.

In the case of 2D isometries, this corresponds to adding inversion, giving rotations and mirrors in between the existing ones.

If m divides n, then Dihn has n / m subgroups of type Dihm, and one subgroup Zm. Therefore the total number of subgroups of Dihn (n ≥ 1), is equal to d(n) + σ(n), where d(n) is the number of positive divisors of n and σ(n) is the sum of the positive divisors of n. See list of small groups for the cases n ≤ 8.

Conjugacy classes of reflections

All the reflections are conjugate to each other in case n is odd, but they fall into two conjugacy classes if n is even. If we think of the isometries of a regular n-gon: for odd n there are rotations in the group between every pair of mirrors, while for even n only half of the mirrors can be reached from one by these rotations. Geometrically, in an odd polygon every axis of symmetry passes through a vertex and a side, while in an even polygon there are two sets of axes, each corresponding to a conjugacy class: those that pass through two vertices and those that pass through two sides.

Algebraically, this is an instance of the conjugate Sylow theorem (for n odd): for n odd, each reflection, together with the identity, form a subgroup of order 2, which is a Sylow 2-subgroup ( is the maximum power of 2 dividing

is the maximum power of 2 dividing  ), while for n even, these order 2 subgroups are not Sylow subgroups because 4 (a higher power of 2) divides the order of the group.

), while for n even, these order 2 subgroups are not Sylow subgroups because 4 (a higher power of 2) divides the order of the group.

For n even there is instead an outer automorphism interchanging the two types of reflections (properly, a class of outer automorphisms, which are all conjugate by an inner automorphism).

Automorphism group

The automorphism group of Dihn is isomorphic to the holomorph of Z/nZ, i.e. to Hol(Z/nZ)  and has order

and has order  where

where  is Euler's totient function, the number of k in

is Euler's totient function, the number of k in  coprime to n.

coprime to n.

It can be understood in terms of the generators of a reflection and an elementary rotation (rotation by  , for k coprime to n); which automorphisms are inner and outer depends on the parity of n.

, for k coprime to n); which automorphisms are inner and outer depends on the parity of n.

- For n odd, the dihedral group is centerless, so any element defines a non-trivial inner automorphism; for n even, the rotation by 180° (reflection through the origin) is the non-trivial element of the center.

- Thus for n odd, the inner automorphism group has order 2n, and for n even the inner automorphism group has order n.

- For n odd, all reflections are conjugate; for n even, they fall into two classes (those through two vertices and those through two faces), related by an outer automorphism, which can be represented by rotation by

(half the minimal rotation).

(half the minimal rotation). - The rotations are a normal subgroup; conjugation by a reflection changes the sign (direction) of the rotation, but otherwise leaves them unchanged. Thus automorphisms that multiply angles by k (coprime to n) are outer unless

Examples of automorphism groups

Dih9 has 18 inner automorphisms. As 2D isometry group D9, the group has mirrors at 20° intervals. The 18 inner automorphisms provide rotation of the mirrors by multiples of 20°, and reflections. As isometry group these are all automorphisms. As abstract group there are in addition to these, 36 outer automorphisms, e.g. multiplying angles of rotation by 2.

Dih10 has 10 inner automorphisms. As 2D isometry group D10, the group has mirrors at 18° intervals. The 10 inner automorphisms provide rotation of the mirrors by multiples of 36°, and reflections. As isometry group there are 10 more automorphisms; they are conjugates by isometries outside the group, rotating the mirrors 18° with respect to the inner automorphisms. As abstract group there are in addition to these 10 inner and 10 outer automorphisms, 20 more outer automorphisms, e.g. multiplying rotations by 3.

Compare the values 6 and 4 for Euler's totient function, the multiplicative group of integers modulo n for n = 9 and 10, respectively. This triples and doubles the number of automorphisms compared with the two automorphisms as isometries (keeping the order of the rotations the same or reversing the order).

Generalizations

There are several important generalizations of the dihedral groups:

- The infinite dihedral group is an infinite group with algebraic structure similar to the finite dihedral groups. It can be viewed as the group of symmetries of the integers.

- The orthogonal group O(2), i.e. the symmetry group of the circle, also has similar properties to the dihedral groups.

- The family of generalized dihedral groups includes both of the examples above, as well as many other groups.

- The quasidihedral groups are family of finite groups with similar properties to the dihedral groups.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dihedral groups. |

- Dicyclic group

- Coordinate rotations and reflections

- Dihedral group of order 6

- Dihedral group of order 8

- Dihedral symmetry in three dimensions

- Dihedral symmetry groups in 3D

- Cycle index of the dihedral group

References

- ↑ Dummit, David S.; Foote, Richard M. (2004). Abstract Algebra (3rd ed.). John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 0-471-43334-9.

External links

- Dihedral Group n of Order 2n by Shawn Dudzik, Wolfram Demonstrations Project.

- Dihedral group at Groupprops

![{\begin{matrix}R_{0}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}1&0\\[0.2em]0&1\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&R_{1}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}0&-1\\[0.2em]1&0\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&R_{2}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}-1&0\\[0.2em]0&-1\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&R_{3}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}0&1\\[0.2em]-1&0\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},\\[1em]S_{0}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}1&0\\[0.2em]0&-1\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&S_{1}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}0&1\\[0.2em]1&0\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&S_{2}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}-1&0\\[0.2em]0&1\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )},&S_{3}={\bigl (}{\begin{smallmatrix}0&-1\\[0.2em]-1&0\end{smallmatrix}}{\bigr )}.\end{matrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/7/6/5/8/765808b9507c5e643ba1eb4cb52ae666.png)

![r_{1}={\begin{bmatrix}\cos {2\pi \over n}&-\sin {2\pi \over n}\\[8pt]\sin {2\pi \over n}&\cos {2\pi \over n}\end{bmatrix}}\qquad s_{0}={\begin{bmatrix}1&0\\0&-1\end{bmatrix}}](/2014-wikipedia_en_all_02_2014/I/media/5/c/f/e/5cfe1877f88bfb9d09e6469da4b02c19.png)