Dielectric elastomers

the electrostatic pressure

the electrostatic pressure  acts. Due to the mechanical compression the elastomer film contracts in the thickness direction and expands in the film plane directions. The elastomer film moves back to its original position when it is short-circuited.

acts. Due to the mechanical compression the elastomer film contracts in the thickness direction and expands in the film plane directions. The elastomer film moves back to its original position when it is short-circuited.Dielectric elastomers (DEs) are smart material systems that produce large strains. They belong to the group of electroactive polymers (EAP). DE actuators (DEA) transform electric energy into mechanical work. They are lightweight and have a high elastic energy density. They have been investigated since the late 1990’s. Many prototype applications exist. Every year, conferences are held in the US[1](registration required)

and Europe.[2]

Working principles

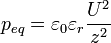

A DEA is a compliant capacitor (see image), where a passive elastomer film is sandwiched between two compliant electrodes. When a voltage  is applied, the electrostatic pressure

is applied, the electrostatic pressure  arising from the Coulomb forces acts between the electrodes. The electrodes squeeze the elastomer film. The equivalent electromechanical pressure

arising from the Coulomb forces acts between the electrodes. The electrodes squeeze the elastomer film. The equivalent electromechanical pressure  is twice the electrostatic pressure

is twice the electrostatic pressure  and is given by:

and is given by:

where  is the vacuum permittivity,

is the vacuum permittivity,  is the dielectric constant of the polymer and

is the dielectric constant of the polymer and  is the thickness of the elastomer film. Usually, strains of DEA are in the order of 10–35%, maximum values reach 300% (the acrylic elastomer VHB 4910, commercially available from 3M, which also sports a high elastic energy density and a high electrical breakdown strength.)

is the thickness of the elastomer film. Usually, strains of DEA are in the order of 10–35%, maximum values reach 300% (the acrylic elastomer VHB 4910, commercially available from 3M, which also sports a high elastic energy density and a high electrical breakdown strength.)

Ionic

Replacing the electrodes with soft hyrdogels allows ionic transport to replace electron transport. Aqueous ionic hydrogels can deliver potentials of multiple kilovolts, despite the onset of electrolysis at below 1.5 V.[3]

The difference between the capacitance of the double layer and the dielectric leads to a potential across the dielectric that can be millions of times greater than that across the double layer. Potentials in the kilovolt range can be realized without electrochemically degrading the hydrogel.[3]

Deformations are well controlled, reversible, and capable of high-frequency operation. The resulting devices can be perfectly transparent. High-frequency actuation is possible. Switching speeds are limited only by mechanical inertia. The hydrogel's stiffness can be thousands of times smaller than the dielectric's, allowing actuation without mechanical constraint across a range of nearly 100% at millisecond speeds. They can be biocompatible.[3]

Remaining issues include drying of the hydrogels, ionic build-up, hysteresis, and electrical shorting.[3]

Early experiments in semiconductor device research relied on ionic conductors to investigate field modulation of contact potentials in silicon and to enable the first solid-state amplifiers. Work since 2000 has established the utility of electrolyte gate electrodes. Ionic gels can also serve as elements of high-performance, stretchable graphene transistors.[3]

Materials

Films of carbon powder or grease loaded with carbon black were early choices as electrodes for the DEAs. Such materials have poor reliability and are not available with established manufacturing techniques. Improved characteristics can be achieved with sheets of graphene, coatings of carbon nanotubes, surface-implanted layers of metallic nanoclusters and corrugated or patterned metal films.[3]

These options offer limited mechanical properties, sheet resistances, switching times and easy integration. Silicones and acrylic elastomers are other alternatives.

The requirements for an elastomer material are:

- The material should have low stiffness (especially when large strains are required);

- The dielectric constant should be high;

- The electrical breakdown strength should be high.

Mechanically prestretching the elastomer film offers the possibility of enhancing the electrical breakdown strength. Further reasons for prestretching include:

- Film thickness decreases, requiring a lower voltage to obtain the same electrostatic pressure;

- Avoiding compressive stresses in the film plane directions.

The elastomers show a visco-hyperelastic behavior. Models that describe large strains and viscoelasticity are required for the calculation of such actuators.

Materials used in research include graphite powder, silicone oil / graphite mixtures, gold electrodes. The electrode should be conductive and compliant. Compliance is important so that the elastomer is not constrained mechanically when elongated.[3]

Films of polyacrylamide hydrogels formed with salt water can be laminated onto the dielectric surfaces, replacing electrodes.[3]

Configurations

Configurations include:

- Framed/In-Plane actuators: A framed or in-plane actuator is an elastomeric film coated/printed with two electrodes. Typically a frame or support structure is mounted around the film. Examples are expanding circlesp and lanars (single and multiple phase.)

- Cylindrical/Roll actuators: Coated elastomer films are rolled around an axis. By activation, a force and an elongation appear in the axial direction. The actuators can be rolled around a compression spring or without a core. Applications include artificial muscles (prosthetics), mini- and microrobots, and valves.

- Diaphragm actuators: A diaphragm actuator is made as a planar construction which is then biased in the z-axis to produce out of plane motion.

- Shell-like actuators: Planar elastomer films are coated at specific locations in the form of electrode segments. With a well-directed activation, the foils assume complex three-dimensional shapes. Examples may be utilized for propelling vehicles through air or water, e.g. for blimps.

- Stack actuators: Stacking planar actuators can increase deformation. Actuators that shorten under activation are good candidates.

- Thickness Mode Actuators: The force and stroke moves in the z-direction (out of plane). Thickness mode actuators are a typically a flat film that may stack layers to increase displacement.

Applications

Dielectric elastomers offer multiple potential applications with the potential to replace many electromagnetic actuators, pneumatics and piezo actuators. A list of potential applications include:

- Haptic Feedback

- Pumps

- Valves

- Robotics

- Prosthetics

- Power Generation

- Active Vibration Control of Structures

- Optical Positioners such for auto-focus, zoom, image stabilization

- Sensing of force and pressure

- Active Braille Displays

- Speakers

- Deformable surfaces for optics and aerospace

- Energy Harvesting

- Noise-canceling windows[3]

- Display-mounted tactile interfaces[3]

- Adaptive optics[3]

References

- ↑ "Conference Detail for Electroactive Polymer Actuators and Devices (EAPAD) XV". Spie.org. 2013-03-14. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ European conference

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 3.4 3.5 3.6 3.7 3.8 3.9 3.10 Rogers, J. A. (2013). "A Clear Advance in Soft Actuators". Science 341 (6149): 968–969. doi:10.1126/science.1243314. PMID 23990550.

Further reading

- Pelrine, R.; Kornbluh, R.; Pei, Q.; Joseph, J. (2000). "High-Speed Electrically Actuated Elastomers with Strain Greater Than 100%". Science 287 (5454): 836–839. doi:10.1126/science.287.5454.836. PMID 10657293.

- Carpi; De Rossi; Kornbluh; Pelrine; Sommer-Larsen (2008). Dielectric elastomers as electromechanical transducers: Fundamentals, materials, devices, models & applications of an emerging electroactive polymer technology. Elsevier.

External links

- Smart Materials & Structures (EAP/AFC) program at Empa

- European Scientific Network for Artificial Muscles

- EuroEAP - International conference on Electromechanically Active Polymer (EAP) transducers & artificial muscles

- WorldWide Electroactive Polymer Actuators * Webhub: Yoseph Bar-Cohen's link compendium at JPL

- Loverich, J. J.; Kanno, I.; Kotera, H. (2006). "Concepts for a new class of all-polymer micropumps". Lab on a Chip 6 (9): 1147–1154. doi:10.1039/b605525g. PMID 16929393.

- Danfoss PolyPower

- The Biomimetics Laboratory at The University of Auckland

- Dielectric Elastomer Stack Actuators (DESA) at Technische Universität Darmstadt

- PolyWEC EU Project: New mechanisms and concepts for exploiting electroactive Polymers for Wave Energy Conversion