Detroit People Mover

| Detroit People Mover | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

Entering Renaissance Center station. | |||

| Background | |||

| Locale | Downtown Detroit | ||

| Transit type | People mover | ||

| Number of lines | 1 | ||

| Number of stations | 13 | ||

| Daily ridership | 7,083 | ||

| Annual ridership | 2,328,084 (FY 2011) | ||

| Headquarters |

1420 Washington Boulevard Detroit, Michigan 48226 | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | 1987 | ||

| Operator(s) | Detroit Transportation Corporation | ||

| Number of vehicles | 12 | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 2.9 mi (4.7 km) | ||

| Track gauge | 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) | ||

| Electrification | Third rail | ||

| |||

The Detroit People Mover is a 2.9-mile (4.7 km) automated people mover system which operates on a single set of tracks, and encircles Downtown Detroit, Michigan.[1]

The People Mover is owned and operated by the Detroit Transportation Corporation, an agency of the City of Detroit.

The Woodward Avenue Light Rail line, beginning construction in 2013, will serve as a link between the Detroit People Mover and SEMCOG Commuter Rail with access to DDOT and SMART buses as part of a comprehensive network of transportation in metropolitan Detroit.[2]

The People Mover uses UTDC ICTS Mark I technology and the cars are driverless. A siding allows the system to be used in a two-way bypass manner when part of the circular track is closed.

History

The Detroit People Mover has its origins in 1966, with Congressional creation of the Urban Mass Transportation Administration (UMTA) to develop new types of transit. In 1975, following the failure to produce any large-scale results and increased pressure to show results, UMTA created the Downtown People Mover Program (DPM) and sponsored a nationwide competition that offered federal funds to cover much of the cost of planning and construction of such a system. Selecting proposals from four cities, the UMTA recommended that Detroit, Miami, and Baltimore be permitted to construct systems, but only if they could do so with existing grants. Though two of the four selected cities ultimately withdrew from the program, Miami and Detroit persevered to build theirs.[3]

The People Mover was intended to be the downtown distributor for a proposed city and metro-wide light rail transit system for Detroit in the early 1980s; however, funding was scaled back.[4] At the time of planning, the system was projected to have a ridership of 67,700 daily.[5]

The People Mover is owned and operated by the Detroit Transportation Corporation (DTC). The DTC was incorporated in 1985 as a Michigan Public Body Corporate for the purpose of acquiring, owning, constructing, furnishing, equipping, completing, operating, improving, enlarging, and/or disposing of the Central Automated Transit Systems (CATS) in Detroit, Michigan. DTC acquired the CATS project from the Suburban Mobile Authority for Regional Transportation (SMART) formerly known as the Southeastern Michigan Transportation Authority (SEMTA), on October 4, 1985. The DTC was created by the City of Detroit, Michigan pursuant to Act 7 of Public Acts of 1967 and is a component unit of the City of Detroit and accounts its activity as per proprietary funds.[6]

The CATS project, aka the Downtown People Mover (DPM), officially opened to the public on July 31, 1987. Prior to November 18, 1988, the People Mover System was operated and maintained by the primary contractor, Urban Transportation Development Corporation (UTDC) on a month to month basis. On November 18, 1988, the DTC assumed the responsibility to operate and maintain the People Mover System.

The system opened in 1987 using the same technology as Vancouver's SkyTrain and Toronto's Scarborough RT line. In the first year, an average of 11,000 riders used the People Mover each day; the one-day record was 54,648.[7]

When the People Mover opened, it traditionally ran counter-clockwise. In August 2008, the system changed direction and is now running clockwise permanently, although it can run in both directions when necessary. The change in direction reduced the time required to complete one round-trip. The clockwise direction has one short, relatively steep uphill climb and then coasts downhill for a majority of the ride, allowing the train to use gravity to accelerate. This makes each round-trip slightly faster than climbing uphill most of the way in a counter-clockwise direction.[8]

Cost-effectiveness and use

The Mover costs $12 million annually in city and state subsidies to run.[9] The cost-effectiveness of the Mover has drawn criticism.[10] In every year between 1997 and 2006, the cost per passenger mile exceeded $3, and was $4.26 in 2009,[11] compared with Detroit bus routes that operate at $0.82[11] (the New York City Subway operates at $0.30 per passenger mile). The Mackinac Center for Public Policy also charges that the system does not benefit locals, pointing out that fewer than 30% of the riders are Detroit residents and that Saturday ridership (likely out-of-towners) dwarfs that of weekday usage.[9] The system was designed to move up to 15 million riders a year. In 2008 it served approximately 2 million riders. In fiscal year 1999-2000 the city was spending $3 for every $0.50 rider fare, according to The Detroit News. In 2006, the Mover filled less than 10 percent of its seats.[9]

Among the busiest periods was the five days around the 2006 Super Bowl XL, when 215,910 patrons used the service.[12] In 2008, the system moved about 7,500 people per day, about 2.5 percent of its daily peak capacity of 288,000.[13][14]

Expansion

There have been proposals to extend the People Mover northward to the New Center and neighborhoods not within walking distance of the city's downtown. A proposal was put forward by Marsden Burger, former manager of the People Mover, to double the length of the route by extending the People Mover along Woodward Avenue to West Grand Boulevard and into the New Center area.[15] New stops would have included the Amtrak station, Wayne State University and the cultural center, the Detroit Medical Center, and the Henry Ford Hospital. The plan was proposed at a tentative cost of $150–200 million, and would have been paid for by a combination of public and private financing.[16] It was ultimately decided that the system would instead be connected to New Center by a streetcar line following much of the proposed route.

Operations and Maintenance

The People Mover system's operations center is located at the Times Square Station. Housed in the same complex is the system's maintenance facility and storage of the cars in an indoor facility.[17] Cars enter south turnout to enter the maintenance facility and exit from the north turn out back onto the main track. Maintenance equipment (work cars, etc...) are lifted up to track level by crane, but not stored with the DPM cars.

Work Cars

Work cars are not maintained or owned by DPM, but by contractors:[18]

- three car Loram rail grinding set (8 stone L-Series Specialty Rail Grinders)

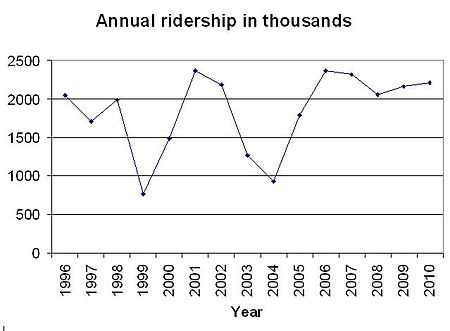

Ridership

| Year | Riders | Source |

|---|---|---|

| 1996 | 2,048,900 | Motown Tranzit |

| 1997 | 1,711,000 | Motown Tranzit |

| 1998 | 1,989,100 | Motown Tranzit |

| 1999 | 763,000 | Motown Tranzit |

| 2000 | 1,485,900 | Motown Tranzit |

| 2001 | 2,370,000 | Detroit News |

| 2002 | 2,186,600 | Motown Tranzit |

| 2003 | 1,267,900 | Motown Tranzit |

| 2004 | 932,400 | |

| 2005 | 1,792,900 | APTA[19] |

| 2006 | 2,368,100 | APTA[20] |

| 2007 | 2,320,600 | APTA[21] |

| 2008 | 2,059,600 | APTA[22] |

| 2009 | 2,161,300 | |

| 2010 | 2,216,200 | APTA[23] |

| 2011 | 2,285,000 | APTA[24] |

| 2012 | ? |

Stations

The DPM stops at 13 stations, eight of which were built into existing buildings. Each station has original artwork. As the system is single tracked, the stations only have a single platform setup.

| Station | Location |

|---|---|

| Broadway Station | Broadway and John R. Street (downtown YMCA) |

| Grand Circus Park Station | Park Street & Woodward Avenue (David Whitney Building) |

| Times Square Station | Grand River Avenue & Times Square |

| Michigan Avenue Station | Michigan Avenue & Cass Avenue |

| Fort/Cass Station | Fort Street & Cass Avenue |

| Cobo Center Station | Cass Street & Congress Street (Cobo Hall) |

| Joe Louis Arena Station | 3rd Street & Jefferson Avenue (Joe Louis Arena) |

| Financial District Station | Larned Street & Shelby Street (150 West Jefferson) |

| Millender Center Station | Milender Center |

| Renaissance Center Station | Renaissance Center |

| Bricktown Station | Beaubien Street & East Fort Street |

| Greektown Station | East Lafayette Street (Greektown Historic District) |

| Cadillac Center Station | Gratiot Avenue & Library Street |

Public Art

Each station displays artwork created by various artists:

- Times Square

- In Honor of W. Hawkins Ferry (Artist: Tom Phardel / Pewabic Pottery - glazed tile)

- Untitled (Artist: Anat Shiftan / Pewabic Pottery - tile mural)

- Michigan Ave

- Voyage (Artist: Allie McGhee - tile mural)

- On the Move (Artist: Kirk Newman - cast bronze shape on tile)

- Fort/Cass

- Untitled (Artist: Farley Tobin - tile mural)

- Progression II (Artist: Sandra jo Osip - bronze sculpture)

- Cobo Center

- Calvacade of Cars (Artist: Larry Ebel/Linda Cianciolo Scarlett - mural)

- Joe Louis Arena

- Voyage (Artist: Gerome Kamrowski - venetian glass mosaic)

- Financial District

- 'D' for Detroit (Artist: Joyce Kozloff - hand painted ceramic mural)

- Millender Center

- Detroit New Morning (Artist: Alvin Loving Jr - painted glazed tiles

- Renaissance Center

- Siberian Ram (Artist: Marshall Fredericks - cast bronze sculpture)

- Bricktown

- Baudien Passage (Artist: Glen Michaels - bas relief on porcelain panels)

- Greektown

- Neon for the Greektown Station (Artist: Stephen Antomakos - free form neon light display)

- Cadillac Center

- In Honour of Mary Chase Stratton (Artist: Diana Kulisek/Pewabic Pottery - tile mural interspersed with bronze plaque by Carlos Romanelli 1903)

- Broadway

- The Blue Nile (Artist: Charless McGee - painted mural panels)

- Grand Circus Park

- Catching Up (Artist: J. Seward Johnson Jr - bronze statue)

Rolling stock

- Manufacturer: Urban Transportation Development Corporation (now Bombardier Transportation)

- Type: ICTS Mark I

- # of cars: 12 cars

- Maximum speed: 56 mph[1]

The system operates in 2 car pairs.

See also

- List of rapid transit systems

- List of United States rapid transit systems by ridership

- Transportation in metropolitan Detroit

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "The Detroit People Mover - Overview". Thepeoplemover.com. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Ann Arbor - Detroit Regional Rail Project SEMCOG. Retrieved on February 4, 2010.

- ↑ "The Downtown People Mover Program". Faculty.washington.edu. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Phillipp Oswalt. "Shrinking Cities,". p. 93. Retrieved 2009-09-07.

- ↑ Wendell Cox. "Analysis of the Proposed Las Vegas LLC Monorail". p. 14. Retrieved 2007-09-20.

- ↑ "Summary of Significant Account Policies". p. 12.

- ↑ "Detroit downtown peoplemover, advanced automated urban transit". Faculty.washington.edu. 2008-06-29. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ "Detroit People Mover Reopens and Makes Changes". Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 People Mover grows up

- ↑ Braun, Ken (2007-12-11). "The Detroit People Mover Still Serves as "a Rich Folks’ Roller Coaster" [Michigan Capitol Confidential]". Mackinac.org. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 "Pricey pensions for Detroit's roller-coaster for rich people". Speroforum.com. 2011-02-27. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Detroit Transportation Corporation

- ↑

- ↑ Luczak, Marybeth (1998). "Is there people-mover in your future?". Railway Age.

- ↑ "DetroitPeopleMover2". Drcurryassociates.net. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ Detroit News

- ↑ "Times Square(Detroit People Mover)". The SubwayNut. 2011-10-28. Retrieved 2013-07-26.

- ↑ http://www.thepeoplemover.com/resource/attach/28/DTCrailgrindingtechSpecMar102of3.doc

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2005" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 4 Apr 2006. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

- ↑ "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2006" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 12 Mar 2007. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

- ↑ "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2007" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 5 Mar 2008. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

- ↑ "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2008" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 5 Mar 2009. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

- ↑ "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2010" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 8 Mar 2011. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

- ↑ "Public Transportation Ridership Report Fourth Quarter 2011" (PDF). American Public Transportation Association. 24 Feb 2012. Retrieved 14 Mar 2013.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Detroit People Mover. |

External links

- Official site

- YouTube: On-Ride Video of the Detroit People Mover (June 2012)

| ||||||||

| |||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||