Dermatobia hominis

| Dermatobia hominis | |

|---|---|

| |

| Adult female human botfly | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Diptera |

| Family: | Oestridae |

| Subfamily: | Cuterebrinae |

| Genus: | Dermatobia |

| Species: | D. hominis |

| Binomial name | |

| Dermatobia hominis (Linnaeus Jr in Pallas, 1781) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Oestrus hominisLinnaeus Jr in Pallas, 1781 | |

The human botfly, Dermatobia hominis, (Greek δέρμα, skin + βίος, life, and Latin hominis, of a human) is one of several species of fly the larvae of which parasitise humans (in addition to a wide range of other animals, including other primates[1]). It is also known as the torsalo or American warble fly,[1] even though the warble fly is in the genus Hypoderma and not Dermatobia and is a parasite on cattle and deer instead of humans.

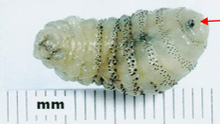

Dermatobia fly eggs have been shown to be vectored by over 40 species of mosquitoes and muscoid flies, as well as one species of tick;[2] the female captures the mosquito and attaches its eggs to its body, then releases it. Either the eggs hatch while the mosquito is feeding and the larvae use the mosquito bite area as the entry point, or the eggs simply drop off the muscoid fly when it lands on the skin. The larvae develop inside the subcutaneous layers, and after approximately eight weeks, they drop out to pupate for at least a week, typically in the soil. The adults are large flies resembling bumblebees. They are easily recognized because they lack mouthparts (as is true of other Oestrid flies).

This species is native to the Americas from Southeastern Mexico (beginning in central Veracruz) to northern Argentina, Chile, and Costa Rica[1] though it is not abundant enough (nor harmful enough) ever to attain true pest status. Since the fly larvae can survive the entire eight-week development only if the wound does not become infected, it is rare for patients to experience infections unless they kill the larva without removing it completely. It is even possible that the fly larva may itself produce antibiotic secretions that help prevent infection while it is feeding.[citation needed]

Remedies

Recently, physicians have discovered that venom extractor syringes can remove larvae with ease at any stage of growth. As these devices are a common component of first-aid kits, this is an effective and easily accessible solution.[3]

A larva has been successfully removed by first applying several coats of nail polish to the area of the larva's entrance, weakening it by partial asphyxiation.[4]

Covering the location with adhesive tape would also result in partial asphyxiation and weakening of the larva, but is not recommended because the larva's breathing tube is fragile and would be broken during the removal of the tape, leaving most of the larva behind.[4]

The easiest and most effective way to remove botfly larvae is to apply petroleum jelly over the location, which prevents air from reaching the larva, suffocating it. It can then be removed with tweezers safely after a day.

Oral use of ivermectin, an antiparasitic avermectin medicine, has proved to be an effective and non invasive treatment that leads to the spontaneous emigration of the larva.[5] This is especially important for cases where the larva is located at inaccessible places like inside the inner canthus of the eye.

_Region.png)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dermatobia hominis. |

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 "Human Bot Fly Myiasis". U.S. Army Center for Health Promotion and Preventive Medicine. August 2007. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Piper, Ross (2007). "Human Botfly". Extraordinary Animals: An Encyclopedia of Curious and Unusual Animals. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 192–194. ISBN 0-313-33922-8. OCLC 191846476. Retrieved 2009-02-13.

- ↑ Boggild, Andrea K.; Jay S. Keystone and Kevin C. Kain (August 2002). "Furuncular myiasis: a simple and rapid method for extraction of intact Dermatobia hominis larvae". Clinical Infectious Diseases 35 (3): 336–338. doi:10.1086/341493. PMID 12115102. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bhandari, Ramanath; David P. Janos and Photini Sinnis (March 2007). "Furuncular myiasis caused by Dermatobia hominis in a returning traveler". The American journal of tropical medicine and hygiene 76 (3): 598–9. PMC 1853312. PMID 17360891. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Wakamatsu, Wakamatsu; Pierre-Filho (October 2005). "Ophthalmomyiasis externa caused by Dermatobia hominis: a successful treatment with oral ivermectin". Eye 20 (9): 1088–90. doi:10.1038/sj.eye.6702120. Retrieved 2013-06-01.

External links

- Case Report: Insect Bite Reveals Botfly Myiasis in an Older Woman

- Young botfly larvae (about 3 weeks old) just minutes after having been extracted from an arm

- human bot fly on the UF / IFAS Featured Creatures Web site

- Sampson CE, MaGuire J, Eriksson E (February 2001). "Botfly myiasis: case report and brief review". Annals of plastic surgery 46 (2): 150–2. doi:10.1097/00000637-200102000-00011. PMID 11216610. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- Schwartz E, Gur H (2002). "Dermatobia hominis myiasis: an emerging disease among travelers to the Amazon basin of Bolivia". Journal of travel medicine : official publication of the International Society of Travel Medicine and the Asia Pacific Travel Health Association 9 (2): 97–9. doi:10.2310/7060.2002.21503. PMID 12044278.

- Passos MR, Barreto NA, Varella RQ, Rodrigues GH, Lewis DA (June 2004). "Penile myiasis: a case report". Sexually transmitted infections 80 (3): 183–4. doi:10.1136/sti.2003.008235. PMC 1744837. PMID 15169999. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

- Denion E, Dalens PH, Couppié P, et al. (October 2004). "External ophthalmomyiasis caused by Dermatobia hominis. A retrospective study of nine cases and a review of the literature". Acta ophthalmologica Scandinavica 82 (5): 576–84. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0420.2004.00315.x. PMID 15453857. Retrieved 2008-10-09.

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||