Depression position finder

How It Worked

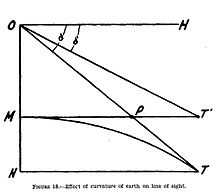

A depression position finder (DPF) measured the range to a distant target (such as a ship) by solving a right triangle in which the short side was the height the instrument above mean low water, one angle was the constant right angle between the short side and the plane of the ocean, and the second angle was the depression angle from the horizontal of the instrument as it sighted down from a fire control tower or a base end station at the target. These calculations were "built into" the scales and gearing of the instrument, which also corrected for the curvature of the earth and for optical parallax, so the horizontal range to the target could be read off of a dial on the DPF.[2]

One soldier looked through the telescope (a 12 or 20-power instrument) and "waterlined" the target ship, putting a vertical cross hair on the ship's forward stack and a horizontal crosshair on the ship's waterline. By turning a geared crank, he attempted to hold the ship in his sights as it passed through his field of view. A second soldier read azimuth and range data from the instrument at designated intervals. These intervals (usually set at 20 or 30 seconds) were indicated by the ringing of a time-interval bell or buzzer (shown in the image at right on the ceiling over the instrument). This information was then called in by telephone to a fire control center or plotting room for the gun battery that had been selected to fire upon the designated target.

The DPF instrument was meant to be used to locate targets at ranges of between 1,500 and 12,000 yards. Its effective range depended upon its height above mean low water,[3] the viewing conditions (lighting, weather, fog or smoke) and upon the skill of its operators in holding a "sight" on a target. From about 1900 to 1925, DPF instruments were often mounted for stability on massive, octagonal concrete columns perhaps two feet across and buried deeply in the ground. A wooden or lath and plaster fire control tower or base end station was then built up around, but not connected to, the column.[4][5]

The DPF could be used as part of a vertical base system of triangulation to compute the range to the target. It could also be used as part of a horizontal base system, in which it served as one of two base end stations, both of which measured an observing angle to the target, with the range and azimuth of the target being calculated from their joint observations.

During the early part of the 20th Century, DPF instruments were often installed in the Battery Commanders' stations for coast artillery batteries and were used by the Battery Commander or a member of his staff to yield firing data (range and azimuth, or direction) for the guns. This system was generally much less accurate than the horizontal base system (based on observations from two widely separated base end stations), and became a back-up system that was used only in emergencies (such as damage to other observation stations).

See also

References

- ↑ A description of one of the earliest operational DPF instruments can be found in "The Service of Coast Artillery," Frank T. Hines and Franklin W. Ward, Goodenough & Woglom Co., New York, 1910, p. 305.

- ↑ For an explanation of the use of several more modern types of DPF, see "FM 4-15: Coast Artillery Field Manual, Seacoast Artillery Fire Control and Position Finding, War Department, U.S. Government Printing Office, Washington, 1940, pp. 46-58.

- ↑ The DPF was considered to give accurate ranges for a distance equal to 1,000 yards for each 10 feet of its height above mean low water. See Hines and Ward, op cit., p. 311.

- ↑ The remains of three base end stations with their concrete DPF mounting columns can be seen here. These columns date to about 1910.

- ↑ A section drawing of another fire control building with a DPF mounting column roughly 19 ft. tall is shown here.