Depression of 1920–21

A 1919 parade in Minneapolis for soldiers returning home after World War I. The upheaval associated with the transition from a wartime to peacetime economy contributed to a depression in 1920 and 1921. |

The Depression of 1920–21 was an extremely sharp deflationary recession in the United States, shortly after the end of World War I. It lasted from January 1920 to July 1921.[1] The extent of the deflation was not only large, but large relative to the accompanying decline in real product.[2]

A range of factors have been identified contributing to the depression, many relating to adjustments in the economy following the end of World War I. There was a brief Post-World War I recession immediately following the end of the war which lasted for 7 months. The economy started to grow, though it had not yet completed all the adjustments in shifting from a wartime to a peacetime economy. Factors identified as potentially contributing to the downturn include: returning troops which created a surge in the civilian labor force, a decline in labor union strife, changes in fiscal and monetary policy, and changes in price expectations.

Following the end of the Depression of 1920–21, the Roaring Twenties brought a period of economic prosperity.

Overview

| Economic data for 1920–21 recession[2][3][4] | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Estimate | Production | Prices | Ratio |

| 1920-21 (Commerce) | -6.9% | -18% | 2.6 |

| 1920-21 (Balke&Gordon) | -3.5% | -13% | 3.7 |

| 1920-21 (Romer) | -2.4% | -14.8% | 6.3 |

| 1929-30 | -8.6% | -2.5% | 0.3 |

| 1930-31 | -6.5% | -8.8% | 1.4 |

| 1931-32 | -13.1% | -10.3% | 0.8 |

The recession lasted from January 1920 to July 1921, or 18 months, according to the National Bureau of Economic Research. This was longer than most post-World War II recessions, but was shorter than recessions from 1910–12 and 1913-1914 (24 and 23 months respectively) and significantly shorter than the Great Depression (132 months).[1][5] Estimates for the decline in Gross National Product also vary. The U.S. Department of Commerce estimates GNP declined 6.9%, Nathan Balke and Robert J. Gordon estimate a decline of 3.5%, and Christina Romer estimates a decline of 2.4%.[2][6] There is no formal definition of economic depression, but two informal rules are a 10% decline in GDP or a recession lasting more than three years.[7]

The recession of 1920–21 was characterized by extreme deflation — the largest one-year percentage decline in around 140 years of data.[2] The Department of Commerce estimates 18% deflation, Balke and Gordon estimate 13% deflation, and Romer estimates 14.8% deflation. The drop in wholesale prices was even more severe, falling by 36.8%, the most severe drop since the American Revolutionary War. This is worse than any year during the Great Depression (adding all the years of the Great Depression together, however, yields more severe deflation). The deflation of 1920–21 was extreme in absolute terms, and also unusually extreme given the relatively small decline in gross domestic product.[2]

| Unemployment rate[8] | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Lebergott | Romer |

| 1919 | 1.4% | 3.0% |

| 1920 | 5.2% | 5.2% |

| 1921 | 11.7% | 8.7% |

| 1922 | 6.7 | 6.9% |

| 1923 | 2.4 | 4.8% |

Unemployment rose sharply during the recession. Romer estimates a rise to 8.7% from 5.2% and an older estimate from Stanley Lebergott says unemployment rose from 5.2% to 11.7%. Both agree that unemployment quickly fell after the recession, and by 1923 had returned to a level consistent with full employment.[8] The recession also saw an extremely sharp decline in industrial production. From May 1920 to July 1921, automobile production declined by 60% and total industrial production by 30%.[9] At the end of the recession, production quickly rebounded. Industrial production returned to its peak levels by October 1922. The AT&T Index of Industrial Productivity showed a decline of 29.4%, followed by an increase of 60.1% – by this measure, the recession of 1920–21 had the most severe decline and most robust recovery of any recession between 1899 and the Great Depression.[10] Using a variety of indexes, Victor Zarnowitz found the recession of 1920–21 to have the largest drop in business activity of any recession between 1873 and the Great Depression. (By this measure, Zarnowitz finds the recession to be only slightly larger than the Recession of 1873–79, Recession of 1882–85, Recession of 1893–94 and the recession of 1907–08.)[10]

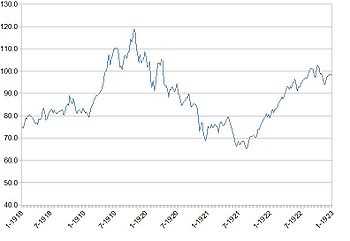

Stocks fell dramatically during the recession. The Dow Jones Industrial Average reached a peak of 119.6 on November 3, 1919, two months before the recession began. The market bottomed on August 24, 1921, at 63.9, a decline of 47% (by comparison, the Dow fell 44% during the Panic of 1907 and 89% during the Great Depression).[11] The climate was terrible for businesses – from 1919 to 1922 the rate of business failures tripled, climbing from 37 failures to 120 failures per every 10,000 businesses. Businesses that avoided bankruptcy saw a 75% decline in profits.[9]

Causes

Factors that economists have pointed to as potentially causing or contributing to the downturn include: troops returning from the war which created a surge in the civilian labor force, a decline in labor union strife, a shock in agricultural commodity prices, tighter monetary policy, expectations of deflation.[2]

End of World War I

Adjusting from war time to peace time was an enormous shock for the U.S. economy. Factories focused on war time production had to shut down or retool their production. A short Post-World War I recession occurred in the United States following Armistice Day, but this was followed by a growth spurt. The recession that occurred in 1920, however, was also affected by the adjustments following the end of the war, particularly the demobilization of soldiers. One of the biggest adjustments was the re-entry of soldiers into the civilian labor force. In 1918, the Armed Forces employed 2.9 million people. This fell to 1.5 million in 1919 and a mere 380,000 by 1920. The impact on the labor market was most striking in 1920, when the civilian labor force increased by 1.6 million people, or 4.1%, in a single year (though smaller than Post-World War II demobilization in 1946 and 1947, it is otherwise the largest documented one-year labor force increase).[2] In the early 1920s, both prices and wages changed more quickly than today, and thus employers may have been quicker to offer reduced wages to returning troops, hence lowering their production costs, and lowering their prices.[2]

Labor unions

During World War I, labor unions had increased their power—the government had great need for goods and services, and with so many young men in the military, there was a tight labor market. Following the war, however, there was a period of turmoil for labor unions, as they lost their bargaining power. In 1919, 4 million workers went on strike at some point, significantly more than the 1.2 million in the preceding years.[2] Major strikes included an iron and steel workers strike in September 1919, a bituminous coal miners strike in November 1919 and a major railroad strike in 1920. According to economist J.R. Vernon, however, "By the spring of 1920, with unemployment rates rising, labor ceased its aggressive stance and labor peace returned."[2]

Monetary policy

Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, in A Monetary History of the United States, consider mistakes in Federal Reserve policy as a key factor in the crisis. In response to post-World War I inflation the Federal Reserve Bank of New York began raising interest rates sharply. In December 1919 the rate was raised from 4.75% to 5%. A month later it was raised to 6% and in June 1920 it was raised to 7% (the highest interest rates of any period except the 1970s and early 1980s).

Deflationary expectations

Under the Gold Standard, a period of significant inflation of bank credit and paper claims would be followed by a wave of redemptions as depositors and speculators moved to secure their assets. This would lead to a deflationary period as bank credit and claims diminished and the money supply contracted in line with gold reserves. The introduction of the Federal Reserve System in 1913 had not fundamentally altered this link to gold.[12] The economy had been generally inflationary since 1896, and from 1914 to 1920, prices had increased quickly. People and businesses thus expected prices to fall substantially.[2]

Government response

President Woodrow Wilson's slow response to the depression was criticized by those in the Republican party, catapulting them into the White House under the banner of Warren Harding. Once in office, he convened a President's Conference on Unemployment at the instigation of then Commerce Secretary Herbert Hoover as a result of rising unemployment during the recession. About 300 eminent members of industry, banking and labor were called together in September 1921 to discuss the problem of unemployment. Hoover organized the economic conference and a committee on unemployment. The committee established a branch in every state having substantial unemployment, along with sub-branches in local communities and mayors' emergency committees in 31 cities. The committee contributed relief to the unemployed, and also organized collaboration between the local and federal governments. President Warren G. Harding signed the Emergency Tariff of 1921 and the Fordney–McCumber Tariff.

However, by the time Harding had called his conference, the countries economy had already shown signs of rebound,[13] and merely allowed for President Harding to claim success.

Interpretations of the end

Some economists and historians argue that the 1921 recession was a necessary market correction, required to engineer the massive realignments required of private business and industry following the end of the War. Historian Thomas Woods argues that President Harding's laissez-faire economic policies during the 1920-21 recession, combined with a coordinated aggressive policy of rapid government downsizing, had a direct influence (mostly through intentional non-influence) on the rapid and widespread private-sector recovery.[14] Woods argued that, as there existed massive distortions in private markets due to government economic influence related to World War I, an equally massive "correction" to the distortions needed to occur as quickly as possible to realign investment and consumption with the new peace-time economic environment.

Daniel Kuehn's recent research calls into question many of the assertions Woods makes about the 1920-21 recession.[15] Kuehn argues that the most substantial downsizing of government was attributable to the Wilson administration, and occurred well before the onset of the 1920-21 recession. Kuehn notes that the Harding administration raised revenues in 1921 by expanding the tax base considerably at the same time that it lowered rates. Kuehn also argues that Woods underemphasizes the role the monetary stimulus played in reviving the depressed economy and that, since the 1920-21 recession was not characterized by a deficiency in aggregate demand, fiscal stimulus was unwarranted. Economist Paul Krugman, who is critical of the Austrian interpretation, notes that the monetary base expanded significantly from 1922-1925, and that this expansion was accompanied by a reduction in commercial paper rates.[16] Allan Meltzer suggests that deflation and the flight of gold from hyper-inflationary Europe to the U.S. also contributed to the rising real money stock and economic recovery.[17]

See also

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 US Business Cycle Expansions and Contractions, National Bureau of Economic Research. Retrieved on September 22, 2008.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 2.9 2.10 Vernon, J.R., "The 1920-21 Deflation: The Role of Aggregate Supply," Economic Inquiry, Vol. 29, 1991.

- ↑ Lawrence H. Officer, "The Annual Consumer Price Index for the United States, 1774-2008," MeasuringWorth, 2009. URL: http://www.measuringworth.org/uscpi/

- ↑ Louis D. Johnston and Samuel H. Williamson, "What Was the U.S. GDP Then?" MeasuringWorth, 2008. URL: http://www.measuringworth.org/usgdp/

- ↑

- ↑ Christina Duckworth Romer (1988). "World War I and the postwar depression; A reinterpretation based on alternative estimates of GNP". Journal of Monetary Economics 22 (1): 91–115.

- ↑ "Diagnosing depression". The Economist. December 30, 2008.

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Romer, Christina (1986). "Spurious Volatility in Historical Unemployment Data". The Journal of Political Economy 91: 1–37.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Anthony Patrick O'Brien (1997). "Depression of 1920–1921". In David Glasner, Thomas F. Cooley. Business cycles and depressions: an encyclopedia. New York: Garland Publishing. pp. 151–153.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Zarnowitz, Victor (1996). Business Cycles. University of Chicago Press.

- ↑ "Dow Historical Timeline". Dow Jones Industrial Average.

- ↑ A Reconsideration of Federal Reserve Policy during the 1920-1921 Depression, Elmus R. Wicker, The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 26, No. 2 (Jun., 1966), pp. 223-238, http://www.jstor.org/stable/2116229

- ↑ "The Growth of the Federal Government in the Early Twentieth Century". May 20, 2011.

- ↑ Thomas Woods. "Warren Harding and the Forgotten Depression of 1920", video.

- ↑ "A critique of Powell, Woods, and Murphy on the 1920–1921 depression "

- ↑ Krugman, Paul (April 1, 2011). "1921 and All That". The New York Times.

- ↑ http://www2.tepper.cmu.edu/afs/andrew/gsia/meltzer/Munich.PDF

External links

- Business Cycles and Unemployment, introduction by Herbert Hoover, Secretary of Commerce, published in 1923.

- THE LONG-RANGE PLANNING OF PUBLIC WORKS, by Otto T. Mallery, Member of the Pennsylvania State Industrial Board, 1923

- "Wage Adjustment and Aggregate Supply in the Depression of 1920-1921: Extending the Bernanke-Carey Model," by Bryan Caplan

- Smiley, Gene. "US Economy in the 1920s". EH.Net Encyclopedia, edited by Robert Whaples. March 26, 2008.

- Wicker, Elmus R. "A Reconsideration of Federal Reserve Policy during the 1920-1921 Depression," Journal of Economic History (1966) 26: 223-238.

| ||||||||||||||||||||