Demographics of Melbourne

| Significant overseas born populations[1] | |

| Place of Birth | Population (2006) |

|---|---|

| 156,457 | |

| 73,801 | |

| 57,926 | |

| 54,726 | |

| 52,453 | |

| 52,279 | |

| 50,686 | |

| 30,594 | |

| 29,174 | |

| 24,568 | |

| 21,182 | |

| 18,951 | |

| 17,317 | |

| 17,287 | |

| 16,917 | |

| 16,439 | |

| 15,367 | |

| 14,645 | |

| 14,581 | |

| 14,124 | |

| 13,546 | |

| 11,580 | |

| Total | 774,600 |

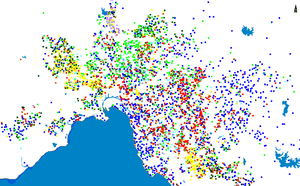

Melbourne is Australia's second largest city and has a diverse and multicultural population.

Melbourne has again dominated Australia's population growth; for the 11th year in a row as of 2013, adding 77,000 people between 2011-2012. It is expected to boom past 5 million people by 2025 and overtake Sydney's declined population growth before 2040. Melbourne currently has over 4.25 million people (peaking at over 5 million at the close to the financial year with an 88+ thousand growth).

Almost a quarter of Victoria's population was born overseas, and the city is home to residents from 180 countries, who speak over 233 languages and dialects and follow 116 religious faiths. Melbourne has the second largest Asian population in Australia, which includes the largest Indian and Sri Lankan communities in the country.[2][3][4]

The earliest known inhabitants of the broad area that later became known as Melbourne were Indigenous Australians – specifically, at the time of European settlement, the Bunurong, Wurundjeri and Wathaurong tribal groups. Melbourne is still a centre of Aboriginal life — consisting of local groups and indigenous groups from other parts of Australia, as most indigenous Victorians were displaced from their traditional lands during colonization – with the Aboriginal community in the city numbering over 20,000 persons (0.6% of the population).[5]

Demographic history

European settlement and Gold Rush immigration

The first European settlers in Melbourne were British and Irish. These two groups accounted for nearly all arrivals before the gold rush, and supplied the predominant number of immigrants to the city until the Second World War.

Melbourne was transformed by the 1850s gold rush; within months of the discovery of gold in August 1852, the city's population had increased by nearly three-quarters, from 25,000 to 40,000 inhabitants.[6] Thereafter, growth was exponential and by 1865, Melbourne had overtaken Sydney as Australia's most populous city.[7]

Large numbers of Chinese, German and United States nationals were to be found on the goldfields and subsequently in Melbourne. The various nationalities involved in the Eureka Stockade revolt nearby give some indication of the migration flows in the second half of the nineteenth century.[8]

Post-war immigration

In the aftermath of the Second World War, Melbourne experienced unprecedented inflows from Mediterranean Europe and the Balkans, primarily Greece, Italy, Bosnia, Croatia, Serbia, Macedonia, and West Asia, mostly from Lebanon, Cyprus and Turkey. According to the 2001 Census, there were 151,785 ethnic Greeks in the metropolitan area.[9] 47% of all Greek Australians live in Melbourne.[10] Ethnic Chinese and Vietnamese also maintain significant presences.

Socioeconomics

Areas within the Greater Melbourne area host varying groups of socio economic background, inner city areas tend to be more affluent, gentrified or bohemian, suburban areas tend to house middle class residents, whilst outer suburban areas tend to house lower income residents.

Other points of note include increased property prices in public transport corridors, leading to many of these areas, particularly in the inner east, being more affluent.

Ethnic groups and multiculturalism

Melbourne does enjoy comparatively high levels of migrant integration to the other capital cities, however some ethnic groups are associated with the suburb in which they first settled:

- Italian with Carlton and Brunswick

- Macedonian with Thomastown and St Albans

- Indian with South Eastern Suburbs such as Hampton Park and Narre Warren, North Western Suburbs, and South Western Suburbs

- Chinese with CBD, Richmond, Springvale, Glen Waverley, Point Cook and Box Hill

- Greek with Oakleigh, Northcote, Doncaster, Hughesdale, and interspersed in Northern and Eastern Suburbs

- Sri Lankans with Dandenong, Endeavour Hills, Lynbrook, Hallam, South Eastern Suburbs, and North Western Suburbs

- Vietnamese with Richmond, Footscray, St. Albans and Springvale

- Cambodian with Springvale South and Keysborough

- Jewish with North Caulfield, Caulfield, St. Kilda East, and South Eastern Suburbs

- Middle Eastern with Northern and South Western Suburbs

- Maltese with Sunshine, Keilor, St. Albans, and Airport West

- Bosnian, Serb and Croat with St Albans and Springvale

- Filipino with Hoppers Crossing

- Turkish with Broadmeadows

- Lebanese with Coburg

- Russian with Carnegie

- Spanish with Fitzroy

- Somali and Habesha with Flemington, Footscray,

- Sudanese with Noble Park, Footscray,

The cities of Dandenong, Monash, Casey and Whittlesea on Melbourne's fringe are particular current migrant hotspots.[11]

Melbourne exceeds the national average in terms of proportion of residents born overseas: 34.8% compared to a national average of 23.1%. In concordance with national data, Britain is the most commonly reported country of birth, with 4.7%, followed by Italy (2.4%), Greece (2.1%) and then China (1.3%). Melbourne also features substantial Vietnamese, Indian and Sri Lankan-born communities, in addition to recent South African and Sudanese influxes.

Over two-thirds of people in Melbourne speak only English at home (68.8%). Italian is the second most common home language (4.0%), with Greek (3.8%) third and Chinese (3.5%) fourth, each with over 100,000 speakers.[12]

Demographics and Cuisine

As a result of large migrant populations, Melbourne has a proliferation of areas where restaurants, cafes and services of similar international demographic establish, particularly Chinese, Indian, Thai, Vietnamese and Malaysian cuisines. Some of these areas include:

- Central Footscray - Vietnamese, Chinese and African cuisine

- Robinson, Walker and Foster streets, Dandenong - Indian (Little India)

- Thomas Street, Dandenong - Afghan (Afghan Bazaar)

- Central Springvale - Authentic Chinese, Thai, Vietnamese

- Glen Waverley - Chinese and East Asian cuisine

- Lygon Street, southern end, Carlton - Italian cuisine (Little Italy)

- Little Bourke Street, eastern end, Melbourne city - Chinese and East Asian cuisine (Chinatown)

- Central Box Hill - Chinese and East Asian cuisine

- Lonsdale Street, top end, Melbourne city - Greek cuisine

- Sydney Road, Coburg/Brunswick - Turkish

- Victoria Street, Abbotsford/Richmond - Chinese, Vietnamese (Little Saigon)

- Johnston Street, western end, Fitzroy - Spanish/Mexican

- Caulfield & North Caulfield - Kosher Jewish cuisine

- Areas notable for large variety of mixed cuisine - Dandenong, Ormond, Brunswick, Melbourne city

Religion

.jpg)

The 2006 Census records show some 28.3% (1,018,113) of Melbourne residents list their religious affiliation as Catholic.[13] The next highest responses were No Religion (20.0%, 717,717), Anglican (12.1%, 433,546), Eastern Orthodox (5.9%, 212,887) and the Uniting Church (4.0%, 143,552).[13] Buddhists, Muslims, Jews and Hindus collectively account for 7.5% of the population.

Judaism

Four out of ten Australian Jews call Melbourne home. The city is also residence to the largest number of Holocaust survivors of any Australian city,[14] indeed the highest per capita concentration outside Israel itself.[15] To service the needs of the vibrant Jewish community, Melbourne's Jewry have established multiple synagogues, which today number over 30,[16] along with a local Jewish newspaper.[17] Melbourne's largest university - Monash University is named after prominent Jewish general and statesman, John Monash.[18]

Christianity

64% of Melburnians consider themselves Christians. The city has two large cathedrals - St Patrick's (Roman Catholic),[19] and St Paul's (Anglican).[20] Both were built in the Victorian era and are of considerable heritage significance as major landmarks of the city.[21]

Islam

There are approximately 500,000 Muslims that call Australia home and over 100,000 of them live in Melbourne. They are noted for their diversity — from more than 60 countries with wildly disparate cultures.[22] [23]

Sikhism

Sikhism is a small but growing minority religion in Australia, that can trace its origins in the nation to the 1830s. The Sikhs form one of the largest subgroups of Indian Australians with 26,500 adherents according to the 2006 census, having grown from 17,000 in 2001 and 12,000 in 1996[1] [2]. Most adherents can trace their ancestry back to the Punjab region of South Asia, which is currently divided between India and Pakistan. Whereas, as per anecdotal evidence collected by Sikh Council of Australia inc, there are approximately 100,000 Sikhs in Australia and the number of Punjabi speakers is even higher. They are often mistaken for who they are not, due to Sikh men required to wear a "Turban" as one of the 5 articles of faith. The largest Sikh community’s are situated on the Eastern Sea Board, Melbourne, Sydney, Brisbane followed by Adelaide, Perth, Canberra, Cairns, Townsville. Sikh’s also make up a significant population in the town of Woolgoolga near Coffs Harbour, NSW where they own Banana Plantations. There is also a significant Sikh population in Griffith NSW, Renmark SA, associated with Farming. Kahlon Estate’s in Renmark which produce Australia’s Premium Wines are owned by Sikh emigrants

Hinduism

The majority of Australian Hindus live along the Eastern Coast of Australia and are mainly located in Melbourne and Sydney. As a community Hindus live relatively peacefully and in harmony with the local populations. They have established a number of temples and other religious meeting places and celebrate most Hindu festivals.[24]

Buddhism

In 1848, the first large group of Buddhists to come to Australia, came as part of gold rush - most of whom stayed briefly for prospecting purposes rather than mass migration. In 1856, a temple was established in South Melbourne by the secular Sze Yap group. The first specific Australian Buddhist group, the Buddhist Study Group Melbourne, was formed in Melbourne in 1938, however it collapsed during the Second World War.[25]

Irreligion

Melbourne and indeed Australia are highly secularised, with the proportion of people identifying themselves as Christian declining from 96% in 1901 to 64% in 2006 and those who did not state their religion or declared no religion rising from 2% to over 30% over the same period.[26]

Population history, density and growth statistics

| Melbourne population by year | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1836 | 177 | |

| 1854 | 123,000 | (gold rush) |

| 1880 | 280,000 | (property boom) |

| 1956 | 1,500,000 | |

| 1981 | 2,806,000 | |

| 1991 | 3,156,700 | (economic slump) |

| 2001 | 3,366,542 | |

| 2006 | 3,744,373 | |

| 2010 | 4,077,036[27] | (Estimate) |

| 2026 | 5,038,100[28] | (Projected) |

| 2056 | 6,789,200[28] | (Projected) |

| Melbourne urban area density (people/ha) | ||

|---|---|---|

| 1951 | 23.4[29] | |

| 1961 | 21.4[30] | |

| 1971 | 18.1[31] | |

| 1981 | 15.9[32] | |

| 1986 | 16.05[33] | |

| 1991 | 16.8[34] | |

| 1996 | 17.9[35] | |

| 1999 | 17.05[36] | |

| 2001 | 15.9[37] | |

Although Victoria's net interstate migration has fluctuated, the Melbourne statistical division has grown by approximately 50,000 people a year since 2003. Melbourne has now attracted the largest proportion of international overseas immigrants (48,000) finding it outpacing Sydney's international migrant intake, along with having strong interstate migration from Sydney and other capitals due to more affordable housing and cost of living, which have been two recent key factors driving Melbourne's growth.[38][39]

In recent years, Melton, Wyndham and Casey, part of the Melbourne statistical division, have recorded the highest growth rate of all local government areas in Australia. Despite a demographic study stating that Melbourne could overtake Sydney in population by 2028,[40] the ABS has projected in two scenarios that Sydney will remain larger than Melbourne beyond 2056, albeit by a margin of less than 3% compared to a margin of 12% today. However, the first scenario projects that Melbourne's population overtakes Sydney in 2039, primarily due to larger levels of internal migration losses assumed for Sydney.[28]

Melbourne's population density declined following the Second World War, with the private motor car and the lures of space and property ownership causing a suburban sprawl, mainly eastward. After much discussion both at general public and planning levels in the 1980s, the decline has reversed since the recession of the early 1990s.

The city has seen increased density in the inner and western suburbs. Since the 1970s, Victorian Government planning blueprints, such as Postcode 3000 and Melbourne 2030, have aimed to curtail the urban sprawl.[41][42]

See also

- Demographics of Australia

- Birth rate and fertility rate in Australia

- Immigration to Australia

- Melbourne population growth

References

- ↑ "2006 Census Tables : Country of Birth of Person by Year of Arrival in Australia — Melbourne". Australian Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 2008-04-16.

- ↑ "Vicnet Directory Indian Community". Vicnet. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "Vicnet Directory Sri Lankan Community". Vicnet. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ "Vietnamese Community Directory". yarranet.net.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ VicNet — Strategy for Aboriginal Managed Land in Victoria: Draft Report [Part 1-Section 2]

- ↑ Victorian Cultural Collaboration. "Gold!". sbs.com.au. Archived from the original on 2008-07-24. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ The Snowy Mountains Scheme and Multicultural Australia

- ↑ Annear, Robyn (1999). Nothing But Gold. The Text Publishing Company.

- ↑ 2001 Social Atlas for Melbourne abs.gov.au

- ↑ City of Melbourne. "Multicultural communities — Greeks". www.melbourne.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "The streets of our town". The Age. www.theage.com.au. 22 July 2002. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "Demographic Profiling of Victorian Government Website Visitors 2007". egov.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-10-02.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 "QuickStats : Melbourne (Statistical Division)". 2006 Census. www.censusdata.abs.gov.au. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ Holocaust Remembrance in Australian Jewish Communities Judith Berman

- ↑ "The Kadimah & Yiddish Melbourne in the 20th Century". Jewish Cultural Centre and National Library: "Kadima". Retrieved 9 January 2007.

- ↑ "Jewish Community of Melbourne, Australia". Beth Hatefutsoth — The Nahum Goldmann Museum of the Jewish Diaspora. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Welcome to the AJN!". The Australian Jewish News. Archived from the original on 2008-07-29. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ Perry, Roland (2004). Monash: The Outsider who Won A War. Random House.

- ↑ "St Patrick's Cathedral". Catholic Communication, Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "St. Paul's Cathedral, Melbourne". anglican.com.au. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Victorian Architectural Period — Melbourne". walkingmelbourne.com. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Inside Muslim Melbourne". theage.com.au. 27 August 2005. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Census shows non-Christian religions continue to grow at a faster rate". abs.gov.au. 27 June 2007. Retrieved 2012-09-15.

- ↑ "Hindu Temples in Melbourne, VIC". newcomerstooz.info. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Melbourne Buddhist Centre". melbournebuddhistcentre.org. Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "Cultural diversity". 1301.0 - Year Book Australia, 2008. Australian Bureau of Statistics. 7 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- ↑ "3218.0 – Regional Population Growth, Australia, 2009–10". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 31 March 2011. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "3222.0 – Population Projections, Australia, 2006 to 2101". Australian Bureau of Statistics. 4 September 2008. Retrieved 21 November 2011.

- ↑ MMBW (ed.). Melbourne metropolitan planning scheme 1954 : planning scheme ordinance p23. Melbourne and Metropolitan Board of Works.

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics 1961. Found in University and State libraries and some public libraries: Australian Bureau of Statistics (ABS).

- ↑ Australian Bureau of Statistics 1971

- ↑ Maher, C.A. Division of National Mapping and the Australian Bureau of Statistics, ed. Melbourne -- a social atlas [cartographic material] 3 (Atlas of population and housing, 1981 census ; ed.). Canberra : Division of National Mapping and Australian Bureau of Statistics in association with the Institute of Australian Geographers, 1984. ISBN 0-642-51634-0.

- ↑ Social Atlas/"Supermap" Census Data, 1986

- ↑ Social Atlas/"Supermap" Census Data, 1991

- ↑ Victoria. Dept. of Infrastructure (ed.). Report of the Advisory Committee on the Victoria planning provisions (VPPs) / Minister for and Local Government. [Melbourne] : Minister for Planning and Local Government, 1998.

- ↑ "Melbourne Urbanized Area: Statistical Local Areas by Population Density: 1999". www.demographia.com. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ Regional Economic Development in Victoria: Melbourne Statistical Division

- ↑ The Resurgence of Marvellous Melbourne Trends in Population Distribution in Victoria, 1991-1996

- ↑ Article by John O'Leary. Monash University Press

- ↑ "Population pushing Melbourne to top". The Australian. www.theaustralian.news.com.au. 12 November 2007. Retrieved 2008-07-18.

- ↑ "Melbourne 2030 - in summary". Victorian Government, Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE). Retrieved 2008-10-05.

- ↑ "City of Melbourne — Strategic Planning — Postcode 3000". City of Melbourne. Retrieved 2008-10-05.