Flood myth

A flood myth or deluge myth is a symbolic narrative in which a great flood is sent by a deity, or deities, to destroy civilization in an act of divine retribution. Parallels are often drawn between the flood waters of these myths and the primeval waters found in certain creation myths, as the flood waters are described as a measure for the cleansing of humanity, in preparation for rebirth. Most flood myths also contain a culture hero, who strives to ensure this rebirth.[1] The flood myth motif is widespread among many cultures as seen in the Mesopotamian flood stories, the Puranas, Deucalion in Greek mythology, the Genesis flood narrative, and in the lore of the K'iche' and Maya peoples of Central America, the Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwa tribe of Native Americans in North America, and the Muisca people in South America.

Mythologies

The Mesopotamian flood stories concern the epics of Ziusudra, Gilgamesh, and Atrahasis. In the Sumerian King List, it relies on the flood motif to divide its history into preflood and postflood periods. The preflood kings had enormous lifespans, whereas postflood lifespans were much reduced. The Sumerian flood myth found in the Deluge tablet was the epic of Ziusudra, who heard the Divine Counsel to destroy humanity, in which he constructed a vessel that delivered him from great waters.[2] In the Atrahasis version, the flood is a river flood.[3]

Assyriologist George Smith translated the Babylonian account of the Great Flood in the 19th century. Further discoveries produced several versions of the Mesopotamian flood myth, with the account closest to that in Genesis 6–9 found in a 700 BCE Babylonian copy of the Epic of Gilgamesh. In this work, the hero, Gilgamesh, meets the immortal man Utnapishtim, and the latter describes how the god Ea instructed him to build a huge vessel in anticipation of a deity-created flood that would destroy the world. The vessel would save Utnapishtim, his family, his friends, and the animals.[4]

In Hindu mythology, texts such as the Satapatha Brahmana mention the puranic story of a great flood,[5] wherein the Matsya Avatar of Vishnu warns the first man, Manu, of the impending flood, and also advises him to build a giant boat.[6][7][8]

In the Genesis flood narrative, Yahweh decides to flood the earth because of the depth of the sinful state of mankind. Righteous Noah is given instructions to build an ark. When the ark is completed, Noah, his family, and representatives of all the animals of the earth are called upon to enter the ark. When the destructive flood begins, all life outside of the ark perishes. After the waters recede, all those aboard the ark disembark and have God's promise that He will never judge the earth with a flood again. He gives the rainbow as the sign of this promise.[9]

In Plato's Timaeus, Timaeus says that because the Bronze race of Humans had been making wars constantly Zeus got angered and decided to punish humanity by a flood. Prometheus the Titan knew of this and told the secret to Deucalion, advising him to build an ark in order to be saved. After 9 nights and days the water started receding and the arc was landed at mount Parnassus.[10]

Claims of historicity

In ancient Mesopotamia, the excavated cities of Shuruppak, Ur, Kish, Uruk, Lagash, and Ninevah all present evidence of flooding. However, the evidence comes from different times.[11] In Israel, there is no such evidence of a widespread flood.[12]

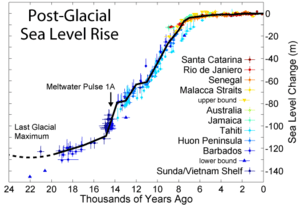

The geography of the Mesopotamian area was considerably changed by the filling of the Persian Gulf after sea waters rose following the last ice age. Global sea levels were about 120m lower up till 18,000 BP and rose till at 8,000 BP they reached the current levels, which are now an average 40m above the floor of the Gulf, which was a huge (800 km (500 mi) x 200 km (120 mi)) low-lying and fertile region in Mesopotamia, in which human habitation is thought to have been strong around the Gulf Oasis for 100,000 years. A sudden increase in settlements above the present water level is recorded at around 7,500 BP.[13][14]

Adrienne Mayor promoted the hypothesis that flood stories were inspired by ancient observations of seashells and fish fossils in inland and mountain areas. The ancient Greeks, Egyptians, Romans all documented the discovery of such remains in these locations; the Greeks hypothesized that Earth had been covered by water on several occasions, citing the seashells and fish fossils found on mountain tops as evidence of this history.[15]

Geologist Ward Sanford has proposed that the filling of the Persian Gulf after the last ice age could have been a catastrophic event giving rise to the flood stories. He proposes a silt dam near the Hormuz Strait which temporarily held back the rising sea levels. "If a breach in the dam was flowing at, say, 100 times the flow of the present-day Tigris and Euphrates, it would have taken several months for the Persian Gulf to fill - the exact sort of timing referred to by the flood account."[16]

Speculation regarding the Deucalion myth has also been introduced, whereby a large tsunami in the Mediterranean Sea, caused by the Thera eruption (with an approximate geological date of 1630–1600 BC), is the myth's historical basis. Although the tsunami hit the South Aegean Sea and Crete it did not affect cities in the mainland of Greece, such as Mycenae, Athens, and Thebes, which continued to prosper, indicating that it had a local rather than a regionwide effect.[17]

Another hypothesis is that a meteor or comet crashed into the Indian Ocean around 3000–2800 BC, created the 30-kilometre (19 mi) undersea Burckle Crater, and generated a giant tsunami that flooded coastal lands.[18]

It has been postulated that the deluge myth in North America may be based on a sudden rise in sea levels caused by the rapid draining of prehistoric Lake Agassiz at the end of the last Ice Age, about 8,400 years ago.[19]

One of the latest, and quite controversial, hypotheses of long term flooding is the Black Sea deluge hypothesis, which argues for a catastrophic deluge about 5600 BC from the Mediterranean Sea into the Black Sea. This has been the subject of considerable discussion.[20][21]

See also

References

- ↑ Leeming, David (2004). "Flood | The Oxford Companion to World Mythology". Oxfordreference.com. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ↑ Bandstra 2009, p. 61, 62.

- ↑ Atrahasis, lines 7-9

- ↑ Pritchard, James B. (ed.), Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1955, 1969). 1950 1st edition at Google Books. p.44: "...a flood [will sweep] over the cult-centers; to destroy the seed of mankind; is the decision, the word of the assembly [of the gods]."

- ↑ The great flood – Hindu style (Satapatha Brahmana).

- ↑ Matsya Britannica.com

- ↑ Klaus K. Klostermaier (2007). A Survey of Hinduism. SUNY Press. p. 97. ISBN 0-7914-7082-2.

- ↑ Sunil Sehgal (1999). Encyclopaedia of Hinduism: T-Z, Volume 5. Sarup & Sons. p. 401. ISBN 81-7625-064-3.

- ↑ Cotter, David W. (2003). Genesis. Collegeville (Minn.): Liturgical press. p. 49. ISBN 0814650406.

- ↑ Plato's Timaeus. Greek text: http://www.24grammata.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/01/Platon-Timaios.pdf

- ↑ Bandstra 2009, p. 61: (Parrot, 1955)

- ↑ Bandstra 2009, p. 62.

- ↑ Lost Civilization Under Persian Gulf?, Science Daily, Dec 8, 2010

- ↑ Rose, Jeffrey I., "New Light on Human Prehistory in the Arabo-Persian Gulf Oasis", Current Anthropology, Vol. 51, No. 6: 849–883, retrieved 2012-02-22

- ↑ Adrienne Mayor (2011). The First Fossil Hunters: Paleontology in Greek and Roman Times: with a new introduction by the author. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0691058636.

- ↑ Sanford, Ward E. (1999), "Thoughts on Eden, the Flood, and the Persian Gulf", Newsletter of the Affiliation of Christian Geologists, retrieved 2013-02-22

- ↑ Castleden, Rodney (2001) "Atlantis Destroyed" (Routledge).

- ↑ Scott Carney (November 7, 2007). "Did a comet cause the great flood?". Discover Magazine. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

- ↑ Early days among the Cheyanne & Arapahoe Indians by John H. Seger, page 135 ISBN 0-8061-1533-5

- ↑ "'Noah's Flood' Not Rooted in Reality, After All?" National Geographic News, February 6, 2009.

- ↑ Sarah Hoyle (November 18, 2007). "Noah's flood kick-started European farming". University of Exeter. Retrieved 17 September 2010.

Bibliography

- Bandstra, Barry L. (2009). Reading the Old Testament : an introduction to the Hebrew Bible (4th ed. ed.). Belmont, CA: Wadsworth/ Cengage Learning. pp. 59–62. ISBN 0495391050.

- Bailey, Lloyd R. Noah, the Person and the Story, University of South Carolina Press, 1989. ISBN 0-87249-637-6

- Best, Robert M. Noah's Ark and the Ziusudra Epic, Sumerian Origins of the Flood Myth, 1999, ISBN 0-9667840-1-4.

- Dundes, Alan (ed.) The Flood Myth, University of California Press, Berkeley, 1988. ISBN 0-520-05973-5 / 0520059735

- Faulkes, Anthony (trans.) Edda (Snorri Sturluson). Everyman's Library, 1987. ISBN 0-460-87616-3.

- Greenway, John (ed.), The Primitive Reader, Folkways, 1965.

- Grey, G. Polynesian Mythology. Whitcombe and Tombs, Christchurch, 1956.

- Lambert, W. G. and Millard, A. R., Atrahasis: The Babylonian Story of the Flood, Eisenbrauns, 1999. ISBN 1-57506-039-6.

- Masse, W. B. "The Archaeology and Anthropology of Quaternary Period Cosmic Impact", in Bobrowsky, P., and Rickman, H. (eds.) Comet/Asteroid Impacts and Human Society: An Interdisciplinary Approach Berlin, Springer Press, 2007. p. 25–70.

- Reed, A. W. Treasury of Maori Folklore A.H. & A.W. Reed, Wellington, 1963.

- Reedy, Anaru (trans.), Nga Korero a Pita Kapiti: The Teachings of Pita Kapiti. Canterbury University Press, Christchurch, 1997.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deluge (mythology). |

- The Great Flood All texts (Eridu Genesis, Atrahasis, Gilgamesh, Bible, Berossus), commentary, and a table with parallels

- Mark Isaak (1996–2002). "Flood stories from around the world". Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- "Mirror from September 2002". Retrieved 2007-06-27.

- Ballard & The Black Sea National Geographic

- Flood Legends from Around the World

- The Flood myth as preserved by the Uru-Muratos of Bolivia's Altiplano on YouTube

- Talkorigins.org

- The BIAMI Legends

- The Genesis Flood and Human History

- The Two Flood Stories; A Comparison of the J and P Accounts Henry E. Neufeld

- Travels of Noah – book written in 1601 telling of the travel of Noah's and the re-population of Europe

- Why Does Nearly Every Culture Have a Tradition of a Global Flood John D. Morris,Ph.D.

- A possible source of the Noah's Flood story Critical review by the Ontario Consultants for Religious Tolerance

- An Anthropologist Looks at the Judeo-Christian Scriptures

- Choctaw Flood Legends Index USA

- Comparison of Babylonian and Noahic Flood Stories

- Flood Stories details of many accounts from around the world

- Flood Stories From Around the World Mark Isaak

- Incan Legends of the Great Flood

- Language Grouping for Flood Stories Mark Isaak

- Morgana's Observatory: Universal Myths Flood Myths Part One

- Flood Myths Part Two

- Myth – Flood N.S. Gill

- Native American Indian Lore: The Great Flood

- The Epic of Gilgamesh Tablet XI – The Story of the Flood

- The Eridu Genesis – The Sumerian Noah

- The Flood, Greek Mythology Link

- The Myth of Noah's Flood Joseph Francis Alward

- The Story of Atrahasis

- A Comparison of Narrative Elements in Ancient Mesopotamian Creation-Flood Stories William H. Shea

- A Statistical Analysis of Flood Legends James E. Strickling CRSQ Abstracts, Volume 9, Number 3

- Aboriginal Flood Legend

- Australian Aboriginal Flood Stories

- Flood Legendsearthage.org

- Flood Legends

- Flood Stories – Can They Be Ignored? by Roth, A. A.

- Flood Traditions by Noahs Ark Zoo Farm

- Flood Traditions of the World Arthur C. Custance

- Genesis and ancient Near Eastern stories of Creation and the Flood

- Grand Canyon Legend