Deltoid muscle

| Deltoid muscle | |

|---|---|

| |

| Deltoid muscle | |

| |

| Muscles connecting the upper extremity to the vertebral column | |

| Latin | musculus deltoideus |

| Gray's | p.439 |

| Origin | the anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle, acromion, spine of the scapula |

| Insertion | deltoid tuberosity of humerus |

| Artery | thoracoacromial artery, anterior and posterior humeral circumflex artery |

| Nerve | Axillary nerve |

| Actions | shoulder abduction, flexion and extension |

| Antagonist | Latissimus dorsi |

| TA | A04.6.02.002 |

| FMA | FMA:32521 |

In human anatomy, the deltoid muscle is the muscle forming the rounded contour of the shoulder. Anatomically, it appears to be made up of three distinct sets of fibers though electromyography suggests that it consists of at least seven groups that can be independently coordinated by the central nervous system.[1]

It was previously called the deltoideus and the name is still used by some anatomists. It is called so because it is in the shape of the Greek letter Delta (triangle). It is also known as the common shoulder muscle, particularly in lower animals (e.g., in domestic cats). Deltoid is also further shortened in slang as "delt". The plural forms of all three incarnations are deltoidei, deltoids and delts.

A study of 30 shoulders revealed an average mass of 191.9 grams (6.77 oz) (range 84 grams (3.0 oz)–366 grams (12.9 oz)) in humans.[2]

Human anatomy

Origins

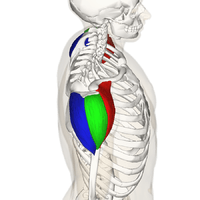

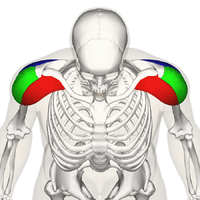

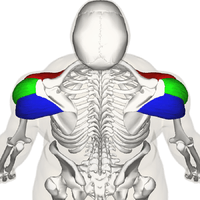

The deltoid originates in three distinct sets of fibers, often referred to as "heads":[3]

- The anterior or clavicular fibers arises from most of the anterior border and upper surface of the lateral third of the clavicle.[4] The anterior origin lies adjacent to the lateral fibers of the pectoralis major muscle as do the end tendons of both muscles. These muscle fibers are closely related and only a small chiasmatic space, through which the cephalic vein passes, prevents the two muscles from forming a continuous muscle mass.[5]

- Lateral or acromial fibers arise from the superior surface of the acromion process.[4]

- Posterior or spinal fibers arise from the lower lip of the posterior border of the spine of the scapula.[4]

Fick[14] divided these three groups of fibers, often referred to as parts (Latin: pars) or bands, into seven functional components:[15] the anterior part has two components (I and II); the lateral one (III); and the posterior four (IV, V, VI, and VII) components. In standard anatomical position (with the upper limb hanging alongside the body), the central components (II, III, and IV) lie lateral to the axis of abduction and therefore contribute to abduction from the start of the movement while the other components (I, V, VI, and VII) then act as adductors. During abduction most of these latter components (except VI and VII which always act as adductors) are displaced laterally and progressively start to abduct.[15]

Insertion

From this extensive origin the fibers converge toward their insertion on the deltoid tuberosity on the middle of the lateral aspect of the shaft of the humerus; the middle fibers passing vertically, the anterior obliquely backward and laterally, and the posterior obliquely forward and laterally.

Though traditionally described as a single insertion, the deltoid insertion is divided into two or three discernible areas corresponding to the muscle's three areas of origin. The insertion is an arch-like structure with strong anterior and posterior fascial connections flanking an intervening tissue bridge. It additionally give off extensions to the deep brachial fascia. Furthermore, the deltoid fascia contributes to the brachial fascia and is connected to the medial and lateral intermuscular septa. [16]

Innervation and blood supply

The deltoid is innervated by the axillary nerve.[17] The axillary nerve originates from the ventral rami of the C5 and C6 cervical nerves, via the superior trunk, posterior division of the superior trunk, and the posterior cord of the brachial plexus.[citation needed]

The axillary nerve is sometimes damaged during operations on the axilla, such as for breast cancer. It may also be injured by anterior dislocation of the head of the humerus.[citation needed]

The deltoid is supplied by the posterior circumflex humeral artery.[17]

Action

When all its fibers contract simultaneously, the deltoid is the prime mover of arm abduction along the frontal plane. The arm must be medially rotated for the deltoid to have maximum effect[citation needed]. This makes the deltoid an antagonist muscle of the pectoralis major and latissimus dorsi during arm adduction.

The anterior fibers are involved in shoulder abduction when the shoulder is externally rotated. The anterior deltoid is weak in strict transverse flexion but assists the pectoralis major during shoulder transverse flexion / shoulder flexion (elbow slightly inferior to shoulders). The anterior deltoid also works in tandem with the subscapularis, pecs and lats to internally (medially) rotate the humerus.[18]

The posterior fibers are strongly involved in transverse extension particularly as the latissimus dorsi is very weak in strict transverse extension. Other transverse extensors, the infraspinatus and teres minor, also work in tandem with the posterior deltoid as external (lateral) rotators, antagonists to strong internal rotators like the pecs and lats. The posterior deltoid is also the primary shoulder hyperextensor, more so than the long head of the triceps which also assists in this function.[19]

The lateral fibers perform basic shoulder abduction when the shoulder is internally rotated, and perform shoulder transverse abduction when the shoulder is externally rotated. They are not utilized significantly during strict transverse extension (shoulder internally rotated) such as in rowing movements, which use the posterior fibers.[20]

An important function of the deltoid in humans is preventing the dislocation of the humeral head when a person carries heavy loads. The function of abduction also means that it would help keep carried objects a safer distance away from the thighs to avoid hitting them, as during a farmer's walk. It also ensures a precise and rapid movement of the glenohumeral joint needed for hand and arm manipulation.[2] The lateral fibers are in the most efficient position to perform this role, though like basic abduction movements (such as lateral raise) it is assisted by simultaneous co-contraction of anterior/posterior fibers.[21]

The deltoid is responsible for elevating the arm in the scapular plane and its contraction in doing this also elevates the humeral head. To stop this compressing against the undersurface of the acromion the humeral head and injuring the supraspinatus tendon, there is a simultaneous contraction of some of the muscles of the rotator cuff: the infraspinatus and subscapularis primarily perform this role. In spite of this there may be still a 1–3 mm upward movement of the head of the humerus during the first 30° to 60° of arm elevation.[2]

Comparison

The deltoid is found in apes other than humans. The human deltoid is of similar proportionate size as the muscles of the rotator cuff in apes like the orangutan, which engage in brachiation and possess the muscle mass needed to support the body weight by the shoulders. In other apes, like the common chimpanzee, the deltoid is much larger than in humans, weighing an average of 383.3g compared to 191.9g in humans. This reflects the need to strengthen the shoulders, particularly the rotatory cuff, in knuckle walking apes for the purpose of supporting the entire body weight.[2]

Spectrum of Findings

The most common abnormalities affecting the deltoid are tears, fatty atrophy, and enthesopathy. Deltoid muscle tears are unusual and frequently related to traumatic shoulder dislocation or massive rotator cuff tears. Muscle atrophy represents the end result of many causes, including aging, disuse, denervation, muscular dystrophy, cachexia, and iatrogenic injury. Deltoideal humeral enthesopathy is an exceedingly rare condition related to mechanical stress. Conversely,deltoideal acromial enthesopathy is likely a hallmark of seronegative spondylarthropathies and its detection should probably be followed by pertinent clinical and serological investigation.[22]

Additional Images

-

Deltoid muscle (shown in red). Animation.

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

-

Deltoid muscle

References

- ↑ Brown JM, Wickham JB, McAndrew DJ, Huang XF. (2007). Muscles within muscles: Coordination of 19 muscle segments within three shoulder muscles during isometric motor tasks. J Electromyogr Kinesiol. 17(1):57-73. PMID 16458022 doi:10.1016/j.jelekin.2005.10.007

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 Potau JM, Bardina X, Ciurana N, Camprubí D. Pastor JF, de Paz F. Barbosa M. (2009). Quantitative Analysis of the Deltoid and Rotator Cuff Muscles in Humans and Great Apes. Int J Primatol 30:697–708. doi:10.1007/s10764-009-9368-8

- ↑ The Anatomy of the Shoulder Muscles: "The Deltoid is a three-headed muscle that caps the shoulder. The three heads of the Deltoid are the Anterior, Lateral, and Posterior."

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 "Deltoid Muscle". Wheeless' Textbook of Orthopaedics. December 2011. Retrieved January 2012.

- ↑ Leijnse, J N A L; Han, S-H; Kwon, Y H (December 2008). "Morphology of deltoid origin and end tendons – a generic model". J Anat 213 (6): 733–742. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7580.2008.01000.x. PMC 2666142. PMID 19094189. Retrieved January 2012.

- ↑ Anterior Deltoid

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Pick up your delts from Muscle and Fitness: "target point: front/middle delts"

- ↑ 8.0 8.1 Lateral deltoid

- ↑ The Best Exercise for Outer Delts on LiveStrong.com in 2011

- ↑ Shoulders Anatomy by Yu Yevon

- ↑ Posterior Deltoid

- ↑ Rear Deltoid Stretch

- ↑ Lee Hayward - Rear delts

- ↑ Fick, R. (1911). Handbuch der Anatomie und Mekanik der Gelenke. Jena: Gustav Fischer.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Kapandji, Ibrahim Adalbert (1982). The Physiology of the Joints: Volume One Upper Limb (5th ed.). New York: Churchill Livingstone.

- ↑ Rispoli, Damian M.; Athwal, George S.; Sperling, John W.; Cofield, Robert H. (2009). "The anatomy of the deltoid insertion". J Shoulder Elbow Surg 18: 386–390. doi:10.1016/j.jse.2008.10.012.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 03:03-0103 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- ↑ Muscles/DeltoidAnterior at exrx.net

- ↑ Muscles/DeltoidPosterior at exrx.net

- ↑ Muscles/DeltoidLateral at exrx.net

- ↑ http://muscleguide.co.uk/exercises/lateral-deltoid-raise.html

- ↑ Arend CF. Ultrasound of the Shoulder. Master Medical Books, 2013. Chapter on deltoideal enthesopathy available at ShoulderUS.com

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Deltoid muscles. |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||