Degree of ionization

The degree of ionization (also known as ionization yield in the literature) refers to the proportion of neutral particles, such as those in a gas or aqueous solution, that are ionized into charged particles. A low degree of ionization is sometimes called partially ionized, and a very high degree of ionization as fully ionized.

Ionization refers to the process whereby an atom or molecule loses an electron, resulting in two oppositely charged particles, (1) a negatively charged electron and (2) a positively charged ion.

Chemistry usage

The degree of ionization, or α, is a way of representing the strength of an acid, often represented by the Greek letter alpha. It is defined as the ratio between the number of ionized molecules and the number of molecules dissolved in water. It can be represented as a decimal number or as a percentage. One can classify strong acids as having ionization degrees above 50%, weak acids with α below 50%, and the remaining as moderate acids, at a specified molar concentration.

Physics usage

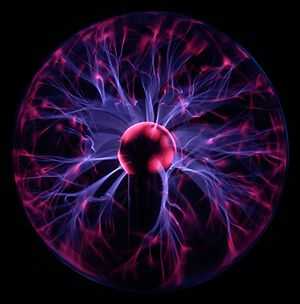

In gases and plasma, the degree of ionization refers to the proportion of neutral particles that are ionized into charged particles. For example, when electricity passes through a novelty plasma ball, perhaps 1% of the gases are ionized (sometimes referred to as partially ionized). Our Sun and all stars contain largely hydrogen and helium gases, that are fully ionized into electrons, protons (H+) and helium ions (He++).

A gas may begin to behave like plasma when the degree of ionization is as little as 0.01%.[1]

History

Ionized matter was first identified in a discharge tube (or Crookes tube), and so described by Sir William Crookes in 1879 (he called it "radiant matter").[3] The nature of the Crookes tube "cathode ray" matter was subsequently identified by English physicist Sir J.J. Thomson in 1897,[4] and dubbed "plasma" by Irving Langmuir in 1928,[5] perhaps because it reminded him of a blood plasma.[6]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Brian Chapman, "Glow discharge plasmas." p49

- ↑ Shibamoto, Takayuki. Introduction to Food Toxicology, 2nd Edition. Academic Press, 2009. p17.

- ↑ Crookes presented a lecture to the British Association for the Advancement of Science, in Sheffield, on Friday, 22 August 1879

- ↑ Announced in his evening lecture to the Royal Institution on Friday, 30 April 1897, and published in Philosophical Magazine, 44, 293

- ↑ I. Langmuir, "Oscillations in ionized gases," Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. U.S., vol. 14, p. 628, 1928

- ↑ G. L. Rogoff, Ed., IEEE Transactions on Plasma Science, vol. 19, p. 989, Dec. 1991. See extract at http://www.plasmacoalition.org/what.htm