Debre Damo

Debre Damo is the name of a flat-topped mountain, or amba, and a 6th-century monastery in northern Ethiopia. The mountain is a steeply rising plateau of trapezoidal shape, about 1000 by 400 meters in dimension. With a latitude and longitude of 14°22′26″N 39°17′25″E / 14.37389°N 39.29028°ECoordinates: 14°22′26″N 39°17′25″E / 14.37389°N 39.29028°E, it sits at an elevation of 2216 meters above sea level. It is located west of Adigrat, in the Mehakelegnaw Zone of the Tigray Region.

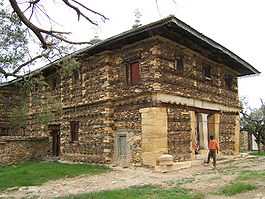

The monastery, accessible only by rope up a sheer cliff, 50 ft. high, is known for its collection of manuscripts and for having the earliest existing church building in Ethiopia still in its original style, and can only be visited by men. Tradition claims the monastery was founded in the sixth century by Abuna Aregawi.

The monastery

The monastery received its first archeological examination by E. Littman who led a German expedition to northern Ethiopia in the early 20th century. By the time David Buxton saw the ancient church in the mid-1940s, he found it "on the point of collapse";[1] a few years later, the English architect D.H. Matthews assisted in the restoration of the building, which included the rebuilding of one of its wood and stone walls (a characteristic style of Aksumite architecture).[2] Thomas Pakenham, who visited the church in 1955, records a tradition that Debre Damo had also once been a royal prison for heirs to the Emperor of Ethiopia, like the better known Wehni and Amba Geshen.[3] The exterior walls of the church were built of alternating courses of limestone blocks and wood, "fitted with the projecting stumps that Ethiopians call 'monkey heads.'" Once inside, Pakenham was in awe of what he saw:

| “ | First we were shown the narthex or ante-chamber. In its dusty ceiling one could dimly make out a series of wood-carvings -- peacocks drinking from a vase, a lion and a monkey, several fabulous animals. These, as I knew, were probably copies from Syrian textiles imported into the country. The designs looked familiar enough -- hardly different from the fabulous beasts that decorate our Romanesque churches. And in fact, as I reflected, the art of Egypt and Syria and Byzantium was developing on similar lines to European art when these panels were being cut. It was a melancholy thought that, ten centuries later, workmanship is not to be had in Ethiopia. | ” |

| “ | When we had gained the nave of the church, the full excitement of the architecture was apparent. The stones holding up the roof piers were actual Axumite relics incorporated in the Christian structure; while the doors and windows which held up the roof were all Axumite in style; their knobbly frames were of exactly the same design as those on the obelisks I had seen at Axum. But the demands of the Christian church had produced entirely un-Axumite features. Below the nave roof a 'clerestory' of wooden windows let in a dim religious light from the outside world. And just visible above the ubiquitous draperies that shrouded the church in hieratic gloom, we could see a chancel arch leading to the sanctuary. It was exciting to see, here in this fortress above the wastes of Moslem Africa, features cast in the strong mould of the basilicas of early Christendom."[4] | ” |