Dead reckoning

In navigation, dead reckoning (also ded (for deduced) reckoning or DR) is the process of calculating one's current position by using a previously determined position, or fix, and advancing that position based upon known or estimated speeds over elapsed time and course.

Dead reckoning is subject to cumulative errors. Advances in navigational aids which give accurate information on position, in particular satellite navigation using the Global Positioning System, have made simple dead reckoning by humans obsolete for most purposes. However, inertial navigation systems, which provide very accurate directional information, use dead reckoning and are very widely applied.

By analogy with their navigational use, the words dead reckoning are also used to mean the process of estimating the value of any variable quantity by using an earlier value and adding whatever changes have occurred in the meantime. Often, this usage implies that the changes are not known accurately. The earlier value and the changes may be measured or calculated quantities.

There is speculation on the etymological origin of the term, but no reliable information.

Errors

Dead reckoning can give the best available information on position, but is subject to significant errors due to many factors as both speed and direction must be accurately known at all instants for position to be determined accurately. For example, if displacement is measured by the number of rotations of a wheel, any discrepancy between the actual and assumed diameter, due perhaps to the degree of inflation and wear, will be a source of error. As each estimate of position is relative to the previous one, errors are cumulative. Or compounding, multiplicatively or exponentially, if that is the co-relationship of the quanta.

Animal navigation

In studies of animal navigation, dead reckoning is more commonly (though not exclusively) known as path integration. Animals use it to estimate their current location based on their movements from their last known location. Animals such as ants, rodents, and geese have been shown to track their locations continuously relative to a starting point and to return to it, an important skill for foragers with a fixed home.[1][2]

Marine navigation

In marine navigation a "dead" reckoning plot generally does not take into account the effect of currents or wind. Aboard ship a dead reckoning plot is considered important in evaluating position information and planning the movement of the vessel.[3]

Dead reckoning begins with a known position, or fix, which is then advanced, mathematically or directly on the chart, by means of recorded heading, speed, and time. Speed can be determined by many methods. Before modern instrumentation, it was determined aboard ship using a chip log. More modern methods include pit log referencing engine speed (e.g. in rpm) against a table of total displacement (for ships) or referencing one's indicated airspeed fed by the pressure from a pitot tube. This measurement is converted to an equivalent airspeed based upon known atmospheric conditions and measured errors in the indicated airspeed system. A naval vessel uses a device called a pit sword (rodmeter), which uses two sensors on a metal rod to measure the electromagnetic variance caused by the ship moving through water. This change is then converted to ship's speed. Distance is determined by multiplying the speed and the time. This initial position can then be adjusted resulting in an estimated position by taking into account the current (known as set and drift in marine navigation). If there is no positional information available, a new dead reckoning plot may start from an estimated position. In this case subsequent dead reckoning positions will have taken into account estimated set and drift.

Dead reckoning positions are calculated at predetermined intervals, and are maintained between fixes. The duration of the interval varies. Factors including one's speed made good and the nature of heading and other course changes, and the navigator's judgment determine when dead reckoning positions are calculated.

Before the 18th-century development of the marine chronometer by John Harrison and the lunar distance method, dead reckoning was the primary method of determining longitude available to mariners such as Christopher Columbus and John Cabot on their trans-Atlantic voyages. Tools such as the Traverse board were developed to enable even illiterate crew members to collect the data needed for dead reckoning. Polynesian navigation, however, uses different wayfinding techniques.

Air navigation

On May 21, 1927 Charles Lindbergh landed in Paris, France after a successful non-stop flight from the United States in the single-engined Spirit of St. Louis. This aircraft was equipped with very basic instruments. He used dead reckoning to find his way.

Dead reckoning in the air is similar to dead reckoning on the sea, but slightly more complicated. The density of the air the aircraft moves through affects its performance as well as winds, weight, and power settings.

The basic formula for DR is Distance = Speed x Time. An aircraft flying at 250 knots airspeed for 2 hours has flown 500 miles through the air. The wind triangle is used to calculate the effects of wind on heading and airspeed to obtain a magnetic heading to steer and the speed over the ground (groundspeed). Printed tables, formulae, or an E6B flight computer are used to calculate the effects of air density on aircraft rate of climb, rate of fuel burn, and airspeed.[4]

A course line is drawn on the aeronautical chart along with estimated positions at fixed intervals (say every 1/2 hour). Visual observations of ground features are used to obtain fixes. By comparing the fix and the estimated position corrections are made to the aircraft's heading and groundspeed.

Dead reckoning is on the curriculum for VFR (visual flight rules - or basic level) pilots worldwide.[5] It is taught regardless of whether the aircraft has navigation aids such as GPS, ADF and VOR and is an ICAO Requirement. Many flying training schools will prevent a student from using electronic aids until they have mastered dead reckoning.

Inertial navigation systems (INSes), which are nearly universal on more advanced aircraft, use dead reckoning internally. The INS provides reliable navigation capability under virtually any conditions, without the need for external navigation references.

Automotive navigation

Dead reckoning is today implemented in some high-end automotive navigation systems in order to overcome the limitations of GPS/GNSS technology alone. Satellite microwave signals are unavailable in parking garages and tunnels, and often severely degraded in urban canyons and near trees due to blocked lines of sight to the satellites or multipath propagation. In a dead-reckoning navigation system, the car is equipped with sensors that know the wheel diameter and record wheel rotations and steering direction. These sensors are often already present in cars for other purposes (anti-lock braking system, electronic stability control) and can be read by the navigation system from the controller-area network bus. The navigation system then uses a Kalman filter to integrate the always-available sensor data with the accurate but occasionally unavailable position information from the satellite data into a combined position fix.

Autonomous navigation in robotics

Dead reckoning is utilized in some lower-end, non mission-critical, or tightly constrained by time or weight, robotic applications. It is usually used to reduce the need for sensing technology, such as ultrasonic sensors, GPS, or placement of some linear and rotary encoders, in an autonomous robot, thus greatly reducing cost and complexity at the expense of performance and repeatability. The proper utilization of dead reckoning in this sense would be to supply a known percentage of electrical power or hydraulic pressure to the robot's drive motors over a given amount of time from a general starting point. Dead reckoning is not totally accurate, which can lead to errors in distance estimates ranging from a few millimeters (in CNC machining) to kilometers (in UAV's), based upon the duration of the run, the speed of the robot, the length of the run, and several other factors.

Pedestrian dead reckoning

With the increased sensor offering in smartphones, built-in accelerometers can be used as a pedometer and built-in magnetometer as a compass heading provider. Pedestrian dead reckoning can be used to supplement other navigation methods in a similar way to automotive navigation, or to extend navigation into areas where other navigation systems are unavailable.

In a simple implementation, the user holds their phone in front of them and each step causes position to move forward a fixed distance in the direction measured by the compass. Accuracy is limited by the sensor precision, magnetic disturbances inside structures, and unknown variables such as carrying position and stride length. Another challenge is differentiating walking from running, and recognizing movements like bicycling, climbing stairs, or riding an elevator.

Before phone-based systems existed, many custom PDR-systems existed. While pedometer can only used to measure linear distance traveled, PDR-systems have embedded magnetometer for heading measurement. Custom PDR-systems can take many forms including special boots, belts, and watches, where the variability of carrying position has been minimized to better utilize magnetometer heading. True dead reckoning is fairly complicated, as it is not only important to minimize basic drift, but also to handle different carrying scenarios and movements, as well as hardware differences across phone models.

Directional dead reckoning

The south-pointing chariot was an ancient Chinese device consisting of a two-wheeled horse-drawn vehicle which carried a pointer that was intended always to aim to the south, no matter how the chariot turned. The chariot predated the navigational use of the magnetic compass, and could not detect the direction that was south. Instead it used a kind of directional dead reckoning: at the start of a journey, the pointer was aimed southward by hand, using local knowledge or astronomical observations e.g. of the Pole Star. Then, as it travelled, a mechanism possibly containing differential gears used the different rotational speeds of the two wheels to turn the pointer relative to the body of the chariot by the angle of turns made (subject to available mechanical accuracy), keeping the pointer aiming in its original direction, to the south. Errors, as always with dead reckoning, would accumulate as distance travelled increased.

Differential steer drive dead reckoning

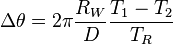

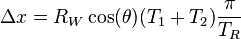

Here are the dead reckoning equations for the coordinates (x and y), and heading ( ) for a differential drive robot with encoders on both drives:

) for a differential drive robot with encoders on both drives:

where  are the encoder ticks recorded on drive one,

are the encoder ticks recorded on drive one,  are the encoder ticks recorded on drive two,

are the encoder ticks recorded on drive two,  is the radius of each drive wheel,

is the radius of each drive wheel,  is the separation between the wheels, and

is the separation between the wheels, and  is the number of encoder ticks recorded in a full rotation of a wheel.

is the number of encoder ticks recorded in a full rotation of a wheel.

Dead reckoning for networked games

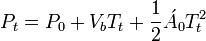

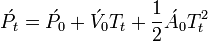

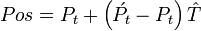

Networked games and simulation tools routinely use dead reckoning to predict where an actor should be right now, using its last known kinematic state (position, velocity, acceleration, orientation, and angular velocity).[6] This is primarily needed because it is impractical to send network updates at the rate that most games run, 60 Hz. The basic solution starts by projecting into the future using linear physics:[7]

This formula is used to move the object until a new update is received over the network. At that point, the problem is that there are now two kinematic states: the currently estimated position and the just received, actual position. Resolving these two states in a believable way can be quite complex. One approach is to create a curve (ex cubic Bézier splines, Catmull-Rom splines, and Hermite curves)[8] between the two states while still projecting into the future. Another technique is to use projective velocity blending, which is the blending of two projections (last known and current) where the current projection uses a blending between the last known and current velocity over a set time.[6]

See also

- Abbe error

- Air navigation

- Attitude and Heading Reference Systems

- Celestial navigation

- Client-side prediction

- Extrapolation

- Inertial navigation system

- Spherical trigonometry

References

- ↑ Gallistel. The Organization of Learning. 1990.

- ↑ Dead reckoning (path integration) requires the hippocampal formation: evidence from spontaneous exploration and spatial learning tasks in light (allothetic) and dark (idiothetic) tests, IQ Whishaw, DJ Hines, DG Wallace, Behavioural Brain Research 127 (2001) 49 – 69

- ↑ http://www.irbs.com/bowditch/pdf/chapt07.pdf

- ↑ "Transport Canada TP13014E Sample Private Pilot Examination". Transport Canada. Retrieved 8 October 2013.

- ↑ "ICAO Annex 1 Paragraph 2.4.4.2.1 h". ICAO. Retrieved 10 September 2013.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Murphy, Curtiss. Believable Dead Reckoning for Networked Games. Published in Game Engine Gems 2, Lengyel, Eric. AK Peters, 2011, p 308-326.

- ↑ Van Verth, James. Essential Mathematics for Games And Interactive Applications. Second Edition. Morgan Kaufmann, 1971, p. 580.

- ↑ Lengyel, Eric. Mathematics for 3D Game Programming And Computer Graphics. Second Edition. Charles River Media, 2004.

External links

- Bowditch Online: "Dead reckoning"

- Straight Dope: Is "dead reckoning" short for "deduced reckoning"?

- Jesse Aronson: "Dead Reckoning: Latency Hiding for Networked Games"

- A paper about pedestrian dead reckoning: "Omni-directional Pedestrian Navigation for First Responders" by Stéphane Beauregard (2006)

- WFR, a Dead Reckoning Robot